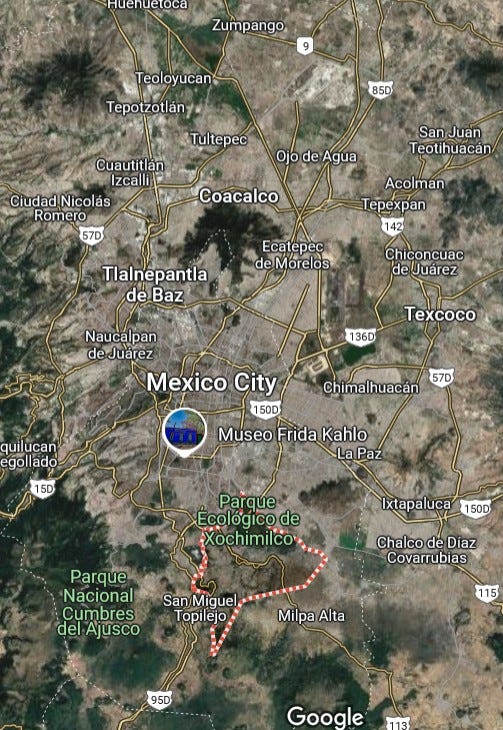

This is my second article reporting in-person from Mexico! It covers my visit to the great Xochimilco Ecological Park in Mexico City and the incredible wildlife conservation, cultural preservation, and climate resilience work being done there by the Humedalia association.

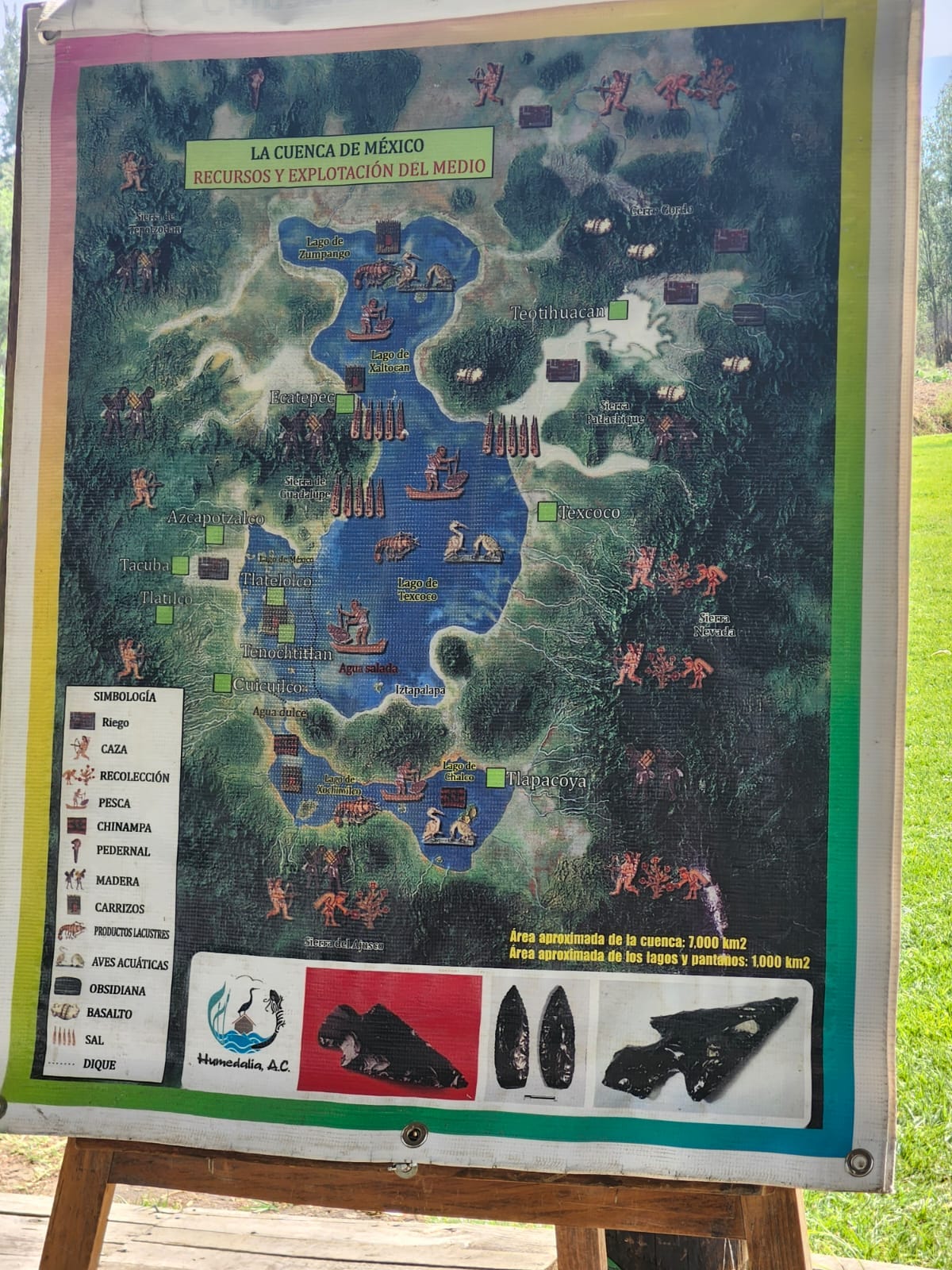

Xochimilco today is a neighborhood within the vast metropolis of Mexico City1, but in pre-Columbian times it was its own altepetl, an independent Mesoamerican city-state within the marshy wetlands on the shores of the great lake system that then occupied the Valley of Mexico. The Xochimilca people were known for their development of the chinampa agricultural system, in artificial islands were painstakingly formed from nutrient-rich mud amidst the waters by multitudes of laborers, creating prime agricultural platforms on which to grow maize2.

When Xochimilco was conquered by the upstart Mexica people of the Tenochtitlan island altepetl in the 1400s3, becoming part of what history would know as the Aztec Empire, the conquerors quickly recognized the utility of their fine-tuned chinampa system, adopting the socio-ecological technology and widely expanding its use. Xochimilco became the breadbasket (or rather maize basket) of the empire and the template for agriculture throughout the Valley of Mexico, with a giant causeway built to assist the omnipresent canoe traffic in sending food and other goods across the lake to the island capital of Tenochtitlan. Then the Spanish invaded in 1519, conquered widely, drained much of the lake system, and the rest is history.

In mid-February 2025, I was remote-working in an inexpensive Airbnb in the streets of modern Xochimilco, writing my newsletters and so on, when I came across the opportunity of spending a day exploring Xochimilco Ecological Park with a fascinating local ecotourism, conservation, climate resilience, and habitat restoration NGO, the Humedalia ecological association. Unlike my sojourn with Dr. Cuauhtemoc Sáenz-Romero, this excursion hadn’t been planned in advance and these folks had never heard of me or my newsletter before. My traveling companion and I were going as ordinary paying visitors on their standard guided canoe tour.

It was simply awesome. From the moment we arrived at the edge between the road and the waters that represented the remaining fraction of the ancient Xochimilcan wetlands, our fields of view thronged with migratory waterbirds, funneled down from across North America to hang out in Mexico for the winter. We got into canoes, and our Humedalia guide Marcos led us to start paddling towards the labyrinthine canals, where even more species appeared before us.

Flocks of imposing white and yellow American pelicans, Pelecanus erthyrorhynchos, thronged the sunnier waterways on the outskirts of the chinampas proper, reminding me of the Louisiana state flag and its depiction of the medieval myth of pelicans feeding their own flesh to their young.

Great blue herons, Ardea herodias, peered out at us from the canals’ edge, instantly familiar yet shockingly incongruous to me as I had only ever before seen the species against the background of New England temperate woodlands.

Great egrets, Egretta thula, seemed to be perched on the water’s edge at every other corner in the canals, sporting magnificent breeding plumage like intricate lace bridal veils cascading from their tails.

And squat bluish night herons, Nycticorax nycticorax, added a brooding Gothic element with the sharp contrast between their dark plumage and strikingly red eyes.

Ever since we entered the wetland, we’d been enjoying relief from the sweltering “urban heat island” effect of paved landscapes in direct sunlight — and breathing easier thanks to the absence of car exhaust and the pleasantly cool and humid atmosphere created by the multitudes of plant life surrounding us. Marcos later informed us that without this remaining wetland patch in Xochimilco, the immediate area’s temperature would likely increase by 3 to 4 degrees Celsius. This little refugium of canals and waterbirds was already providing a local cooling effect larger than the currently projected average global warming by 2100! I remembered writing for my newsletter about the experience of the city of Medellín in Colombia, which had planted 880,000 trees from 2016 through 2021 and found that it cooled their microclimate by 2 degrees Celsius. Local rewilding can bring scalable and immediate climate adaptation benefits.

As we paddled on, passing trajinera party boats on main waterways to move into narrower, calmer canals, Marcos told us how we were entering a vast network of 200 miles of canals crisscrossing the surviving patch of Xochimilco wetland, now a national protected area still within the municipal limits of the capital mega-city. He also gave us a quick overview of the management problems facing the modern Xochimilco Ecological Park. The invasive water hyacinth (Pontederia crassipes) still required active management to limit its dense light-blocking and canoe-tangling floating spread — a common problem in Anthropocene wetland habitats, as it’s one of the fastest-growing plants in the world. Many of the chinampa artificial islands within the park were privately owned, and some had decided to graze cattle there (sometimes they could be fed culled water hyacinth) or set up football (soccer) fields, which were a serious annoyance due to runoff from both herbicides to maintain the artificially grassy expanse and sewage from multitudes of visitors and players using small islands’ inadequate sanitation facilities.

Eventually we arrived at the chinampa owned by Humedalia themselves, a charming little oasis on which organic farming, ecological education, historical recreation, and wildlife education projects coexist and cross-pollinate.

They told us of how the great lakes of the Valley of Mexico has been almost entirely drained over the centuries, starting with the Spanish conquest in the 1500s and continuing through actions by the Mexican government in the 1950s, with only about 2% of the original wetland area left. The water from the surrounding mountains that would have previously flowed into the lost 98% of lakes now flows mostly into Mexico City’s vast sewer system. And in recent years, with climate change, there was a lot less rain than before. Even for the winter dry season, it was unusually dry right now, and the water level at Lake Zumpango, one of the other surviving remnants of the historic great lakes of Mexico, had lowered dangerously. However, even the 2% remainder that we had been exploring today still amounts to a labyrinthine network of over two hundred miles of canals — and a vital climate-adaptation lifeline for the surrounding neighborhood. “Scarcity of water, bad air, heat — wetlands help.”

Excitingly, Mexican planners are starting to integrate these lessons. The lost Valley of Mexico lake system looks to be on the rise again elsewhere in the urban area, finding new forms of coexistence with humanity. North of Xochimilco, the Parque Ecologico Lago de Texcoco project (known by its Spanish acronym PELT) is working to transform an abandoned half-built airport construction site into the world’s largest urban park. PELT is full of ongoing hydrologic engineering efforts to build new water-retaining, air-cooling, and wildlife-supporting ponds and wetlands to help prepare Mexico City for the hot Anthropocene dry seasons to come, and if this mega-project is successful others could become possible.

Back in Xochimilco, we learned that one tree species forms the backbone of the chinampa system: Salix bonplandiana, locally known as the ahuejote tree and known abroad as the Mexican willow or Bonpland willow. Ahuejotes were planted along the edges of the chinampas to help hold the sediment-islands in place with their root systems, and furthermore a basketwork stockade of ahuejote wood surrounded the edge of each chinampa, here and there built out into moorings and jetties for canoes.

Then, we wrapped up the learning session and Marcos took us to see an incredible surprise.

The Humedalia association had permits to help with the conservation of the critically endangered axolotl salamander (Ambystoma mexicanum), and this was one of five individuals currently on or around their chinampa.

Their unique biology has become iconic around the world as a paradigmatic example of neoteny, or retaining juvenile characteristics into reproductive adulthood. Many newt and salamander species have a juvenile aquatic life stage that looks a bit like an axolotl, but the axolotls have somehow evolved to retain their watery way of life and their iconic giant feathery gill-tentacles into adulthood, never metamorphosing to lose the gills and live on land. They also have incredible regeneration abilities, able to grow back severed limbs and critical internal tissues.

As we stared in awe at the “beautiful little monster” in Humedalia’s loving care, we learned that when exposed to the right hormones, adult axolotls can be induced to metamorphose into a non-neotonic form, creating an “super-adult axolotl” that looks like other adult salamanders and never seems to appear in the wild. I was reminded of sci-fi author Larry Niven’s fictional concept of the Pak Protectors, a similar “super-adult stage” of humans that can be triggered by an alien root. The parallel was obvious because I’d read for years about neoteny in humans. Humans are rather like the axolotls of the primates, retaining juvenile traits like big, thin-skulled, large-brained heads to such an extent that human adults resemble other primates’ babies more than other primates’ adults. We’re neotonic grown-up baby chimpanzees to match the neotonic grown-up baby salamanders. And that parallel might be just the start to the axolotl’s historic resonance for our species, as they seem to be able to essentially “pause” aging at the cellular level and have recently become a hub of excited anti-aging research. Just maybe, someday we might learn enough regenerative biology from our amphibian exemplars to further transform what a human life can look like.

The species is critically endangered in the wild, with most of its ancient lake habitat now occupied by Mexico City itself and only a few hundred to a few thousand individuals surviving in patches of Xochimilco Ecological Park. However, there are far more axolotls than that living in captivity among human civilization, in zoos, pet owners’ vivariums, and laboratories. The axolotl has become a widespread model organism for neurological and cardiological research, enabling discoveries to help save human lives while helping ensure an economic motive to keep breeding lots of them in captivity. With their striking appearance, they’ve also become popular icons in the Internet Age, with axolotl-based pop culture references in Pokemon, Minecraft, and the look of the animated Toothless character in the How To Train Your Dragon movies. An axolotl adorns Mexico’s beautiful fifty-peso bill – and at about twenty pesos to the dollar or euro, that’s one of the most common bills in daily use. Like the giant panda in China, axolotls might have attained a “too big to fail” status - it would be international news if they went extinct in the wild in their native Mexico, and hopefully funding for much-needed ongoing conservation and restoration work will keep flowing to ensure that isn’t the case.

And as we tore our gazes away from the wonder of a real-live axolotl in our midst, we learned that Humedalia is already working to help restore a protected micro-population in their ancestral home. Within the protective framework of their chinampa, they’d built an apantle, a micro-canal, shielded from the predators of the broader wetland by a cheap US $120 biofilter and some local tezontle porous volcanic rock. This stewarded linear pond had already became a haven for local biodiversity, with a multitude of invertebrates recorded and snakes and frogs breeding there in the rainy season. Now, Humedalia was working to establish it as a safe haven for these five axolotls, hoping to create a new breeding population. They were out of the apantle now because these precious individuals needed an extra layer of protection beyond the bio-filter, and Humedalia was currently in mid-transition between a smaller and a new, larger in-canal axolotl enclosure. I was thrilled to see these compassionate conservationists and work, and filled with admiration for their drive, resource, and determination to protect and nurture our cousins in Earth’s biosphere.

From the canoe on the way back from the Humedalia chinampa, I caught a lucky photo of a tilapia in a great egret’s beak and learned from Marcos that the non-native papyrus plants at the canals’ edge were viewed as an inoffensive and even helpful species. This ecosystem was another example of the underappreciated complexities often elided by the oversimplified pejorative of “invasive species.” Water hyacinth are indeed a problem matching the traditional concept of “invasiveness,” but the tilapia are a mixed bag, both predating on axolotl eggs and helping feed the indigenous waterbirds, and the papyrus seemed a straightforwardly positive addition that helped clean the water and prevent erosion. Another example of “immigrant species” making good.

As we paddled through the cool, reed-lined, bird-rich waterways, it occurred to me that Ancient Egyptians would feel at home here. Between the papyrus and the tilapia, both native to the Nile, the modern canals of Xochimilco were a passable stand-in for Aaru, the Field of Reeds that was the heavenly afterlife for those whose heart was lighter than the Feather of Truth when weighed in the balance by Anubis. In the ages of the pharaohs, big stretches of the Nile Delta had probably looked a lot like these canals, lined by reeds, leaping with fish, and with flushed waterbirds flying above passing rowing boats. For the first time, I personally grokked why the people of old Kemet had thought a field of reeds was a desirable afterlife to strive for.

Of course, Xochimilco is very much its own unique thing with its own rich associated human cultures, not an ersatz Egypt by any means. Its status as the home waters of axolotls alone makes it an incredibly unique place. But the comparison caught hold of my imagination. Throughout the turbulence of Anthropocene Earth, a kaleidoscopic mix of species, places, peoples, cultures, technologies and ecosystems are forming new mosaics all around the world, often bringing multi-dimensional benefits across domains ranging from biodiversity conservation to urban climate-resilience planning. In addition to the well-documented destruction taking place in our times, fascinating new forms of coexistence and creativity are blossoming alongside and within historic ecologies ensconced in new socioeconomic relationships with humans. Around the world, hardworking people like the stalwarts of Humedalia are working to help nurture and protect that growth, giving life new chances to preserve and renew itself.

Notes from the Valley of Mexico

I spent around a month in the broader Mexico City/Valley of Mexico area before continuing on through Mesoamerica, and in addition to continuing all my regular writing and GIS work I was able in my spare time to learn more about the fascinating cultures and ecologies of the region during a multitude of smaller excursions. Here are a few more points of interest that stood out to me, in no particular order, when visiting Mexico City and environs.

Notes and footnotes available for paid subscribers!

It was fascinating to visit the historic heart of the city - somewhere right near here was the semi-legendary spot where the wandering Mexica tribe had supposedly seen an eagle eating a snake atop a cactus and decided to halt and found Tenochtitlan. Today, a gigantic Mexican flag with that very image at its center floats above the Zocalo, with the presidential palace on one side (I wondered if Claudia Sheinbaum was at home) and the remnants of the Templo Mayor, once the Aztecs’ prize pyramid, just a stone’s throw away. Unlike the comparatively intact ruins of Teotihuacan, this site had been heavily damaged by the Spanish and then half-forgotten for centuries – there was even a municipal sewage pipe running through the middle of the unearthed archaeological site, though some of the ominous sacrifice4 stones have survived.

Chapultepec Park near the city center was a welcoming oasis of green, home to giant ahuehuete trees (Taxodium mucronatum, aka Montezuma cypress, a titan not to be confused with the chinampas’ ahuejote willows), a lake that hosted great egrets just like those we’d seen in the Xochimilcan canals, a fearless green heron that walked within a foot of my boots, and an entry to the stunning National Anthropology Museum, deservedly known as the Louvre of the pre-Columbian American civilizations.

In addition to the Mexican cuisine familiar across America including tacos, burritos, quesadillas, enchiladas, et cetera., I’ve tried for the first time tlayudas, enmoladas, molletes, chimichangas, chilaquiles, flautas, dobladas, enfrijoladas, huaraches, and more since my arrival in Mexico. I was pleasantly surprised by the abundance of vegetarian and vegan options; I’ve been vegetarian for years, and it seemed to me to be considerably easier to maintain a vegetarian diet in Mexico than in the U.S. The Mictlan restaurant in Mexico City, named after the underworld of Aztec myth, is one of the best places to eat I’ve ever been to anywhere in the world – traditional Mexican food, but all vegan, and superbly delicious at amazingly low prices.

Twentieth-century artist Frida Kahlo appears to be worshipped as a goddess across modern central Mexico, with more or less stylized versions of her iconic visage peering out from street art, restaurant wall decorations, hotel signs, and seemingly absolutely every single souvenir and T-shirt shop.

In the charming town of Tepoztlan, just a few hours from Mexico City, my traveling companion and I enjoyed an incredibly steep hike at the top of which was the site of Tepozteco, a little pyramid that had been a temple to Tepoztecatl, god of drunkenness and the local fermented-agave-sap drink pulque. This Mesoamerican Dionysius had attracted pilgrims from as far away as the Maya lands of modern Guatemala, and vessels found at the site indicate that the pleasure and fertility god Xochipilli, “the Flower Prince,” was also worshipped at Tepozteco.

The air pollution in central Mexico City was pretty bad (especially given that it was the dry season), and on its worst days reminded me of Mumbai and Delhi. I quickly developed a persistent hacking cough (the respiratory system has always been my weak point since recovering from childhood asthma), and my glasses seemed to never be clean. The cause was evident all around us: old pre-Clean Air Act models of car thronged the streets, looking like a set from a 1950s or 1960s movie, alongside more modern vehicles and even the occasional horse in some outlying neighborhoods.

Interestingly, in addition to this wide range of methods of transport that appeared old-fashioned from an American perspective, Mexico City’s streets also included “futuristic” cars not yet available in the United States: BYD electric vehicle models straight from China that are currently more or less the best EVs of their kind at world-beating prices. Being there in person and seeing the dawning arrival of futuristic ultra-clean EVs on streets currently choked with car exhaust reminded me of the sheer magnitude of the benefits that the renewables revolution, and the EV transition in particular, will bring to cities across the Global South. I suspect that thousands of lives will be saved and millions of lives will be enhanced by EVs like BYD’s reducing local pollution and massively reducing cases of childhood asthma and other respitatory illnesses.

One absolute highlight of my time in the Valley of Mexico was being able to visit the ruins of the mysterious ancient city of Teotihuacan (not to be confused with the later and further-south Aztec capital Tenochtitlan), which at its height from the 100s through 500s CE was the largest human settlement ever in the Americas. I’d researched this fascinating ancient civilization for my 2023 The Weekly Anthropocene article on the climate crisis of the 530s CE, and being in the neighborhood I couldn’t resist the opportunity to visit the place in person. It was an entire ancient city, astonishingly well-preserved, that had once been the largest-ever human habitation in the Americas. Visitors thronged the Avenue of the Dead through entire neighborhoods of ruined residential buildings and public plazas, with the immense Great Pyramid of the Sun off to the right of the city center and the Great Pyramid of the Moon at the avenue’s terminus. After notable archaeologically visible changes of government5 over the centuries6, the city seems to have fallen in the 500s and 600s CE, likely due to internal unrest after malnutrition due to the climate crisis, and the ruins became a sort of Mount Olympus to successor Mesoamerican civilizations, the home of the gods and the site of great mytho-historical deeds. The Aztecs believed that the sun of our current age – the fifth sun to have illuminated Earth’s sky, in their cosmology – had been created here when the brave Nanahuatzin had sacrificed himself via self-immolation to become the new day-star and deliver the world from darkness after the death of the fourth sun.

The Valley of Mexico is one heck of a fascinating place, and I’m very grateful for the opportunity to visit. While I feel daily anxiety and fear for the fate of my own country, learning more about Mesoamerica’s entrancing ancient civilizations, innovative climate adaptation strategies, unique culture and ecosystems, and incredible wildlife helps me put our time’s terrors in a broader historical context. This too shall pass - and everywhere in the world, people are working to ensure that the legacy that our struggling, half-chaotic global civilization passes on to future humans and animals is as bright as it can be.

With over 20 million people in the Greater Mexico City metro area, it’s by far the largest human settlement on the North American continent, substantially more populous than New York or Los Angeles.

The origin of maize (Zea mays, commonly known as corn in American English) is an incredible story in itself, and I was fascinated to be right in the Mexican heartland where it had happened. In contrast to other major grains like wheat and rice, which have wild ancestors that are fairly similar to the cultivated grains and already able to be processed into human foodstuffs at scale (e.g. wild rice, Einkorn wheat), the wild ancestor of maize was a plant known as teosinte grass that is barely edible and certainly not a promising candidate to become the basis of the Native American agricultural revolution at first glance. Teosinte has only tiny tiny seeds in micro-cobs, looking more like ordinary lawn grass gone to seed than the comparatively gigantic corn-on-the-cob we know today. It took the farsighted work of a generations-long biological Manhattan Project to turn teosinte grass into “Indian corn,” carefully and intentionally created by selective breeding efforts that cultivated the largest seeds of teosinte grass, with seeds and cobs larger each generation, over hundreds and hundreds of years. Today, maize provides about 13% of all calories consumed by humans on Earth, one of the “big three” global crops alongside West Asia-originating wheat and East Asia-originating rice (although the percentages fluctuates year to year). In a very real sense, much of the modern world runs on ancient Mesoamerican biotechnology.

I recalled what I’d been reading in Fifth Sun, the recent one-volume history of the Aztecs. The Mexica people later known as Aztecs had been latecomers to the Valley of Mexico, arriving in the late 1100s to early 1200s from the semi-mythical land of Aztlan somewhere to the north. They’d founded Tenochtitlan on a marshy island in the middle of the lake that wasn’t a great agricultural spot, but this may have worked out to their long-term advantage as their military was available to fight during harvest season — originally as mercenaries for more powerful altepetls, then as a rising power, then as imperial overlords.

Human sacrifice is evil, of course, and the Aztecs’ and other Mesoamericans’ practice of it was a grave atrocity, but according to this writer’s personal amateur grasp of history, it didn’t seem a markedly worse atrocity than the atrocities perpetrated by many other ancient civilizations, many of which seem to get a pass in modern historical memory while the Mesoamericans remain vilified. Having one’s heart cut out by a priest with an obsidian blade likely brought death with much less suffering than being thrown to wild beasts before cheering crowds in the Colosseum. Plus, the Aztecs believed that the blood of their victims fed the sun and helped sustain all life in the world, while Rome knew that the deaths in its gladiatorial arenas were simply for entertainment. Sadly, atrocious mass torture-murder of innocent people is a common recurring feature across much of human history.

At one point, giant temples with spacious quarters exclusively for priests appear to have been converted to more utilitarian uses open to more of the public, with a wall even being built to hide (but not destroy) the facade of a temple to the Feathered Serpent God. One can almost imagine the transition from a “Holy Teotihuacan Empire” to a “Social Republic of Teotihuacan,” whatever the people of the time might have called it.

One fascinating character from Teotihuacan, and one of the few individuals we know anything about, is Spearthrower Owl (so called by archaeologists based on the owl-and-spear name glyph, originally possibly pronounced as Jatz’om Kuy) who may have been a figure rather like a Julius Caesar or Muhammad of Teotihuacan. He appears to have ruled Teotihuacan from the late 300s through early 400s CE, and his name-glyph starts appearing over a really wide area from the Valley of Mexico to the Maya city-states of the Yucatan and modern Guatemala, possibly indicating campaigns of conquest or other widespread influence. Might he also have been somehow involved with the contemporaneous spread of the worship of the Feathered Serpent god, long-venerated in Teotihuacan, later arriving among the Maya, and later known as Quetzalcoatl to the Aztecs and Kukulcan to the Maya?

Thank you!

The “let’s send all water to sewers and then to the ocean” was also done in Los Angeles, and surely a thousand other cities – and they, too, are dismantling those mistakes in a peicemeal fashion