The Dawn of “Immigrant Species Biology”

Let’s read some papers that offer a better, kinder, smarter, and more useful way of thinking about "invasive" species

“Intended Consequences” and the “Species Spectrum”

Two recent scientific papers struck me as powerful forerunners of a more enlightened approach to introduced species, perhaps the beginning of a more sensible field of “immigrant species biology” instead of outmoded and ideology-driven “invasive species biology.” (This third one is also good for a more philosophical treatment of the subject).

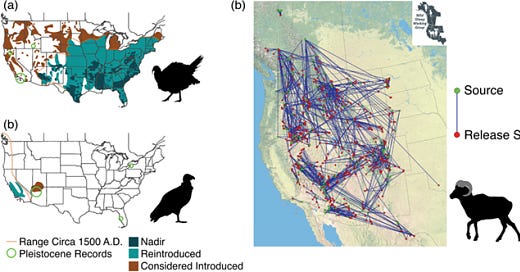

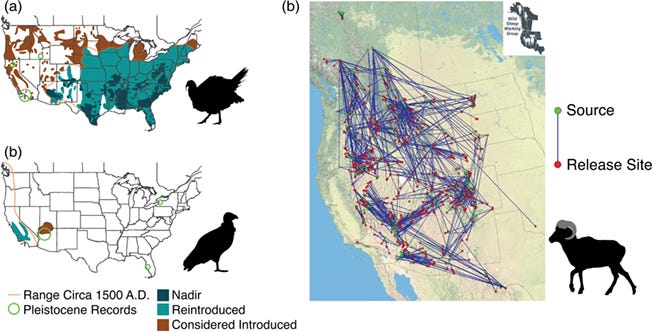

U.S. conservation translocations: Over a century of intended consequences

The research team behind this new paper in Conservation Science and Practice (led by Ben Novak of black-footed ferret cloning and passenger pigeon fame) analyzed the history of species translocations for conservation in the US. They quantified the use of translocations, and found that they were overwhelmingly successful: 70% of 1,580 threatened and endangered taxa in America have had translocations as part of their recovery plan, with only one instance found where this caused a negative impact somewhere. For example, wild turkeys, threatened by overhunting in the early 20th century, have since recovered their numbers-and also been introduced to states like Oregon and Montana that were beyond their original range. California condors, after their near-extinction experience in the 1980s and subsequent captive breeding program, have been introduced to Arizona, where there are no records of condors later than 10,000 years ago. And small groups of bighorn sheep have been moved back and forth between hundreds of sites all over the Rockies in order to help save the species from pneumonia contracted from domestic sheep-a practice which has likely led to excellent genetic diversity. Technically, wild turkeys are “invasive species” in Oregon and California condors are “invasive species” in Arizona, but it’s hard to argue that this “intended consequence” of a conservation relocation isn’t a good thing.

The researchers also examined the history of biological control agents, where one species (often an insect) is introduced to control an invasive or pest species (often a plant). This has been the source of several famous ecosystem-wide screw-ups, including the cane toad and rosy wolf snail examples above. However, they found that this led to negative ecosystem-level effects in only 1.4% of cases, 42 of the 3,014 examples of biological control agent programs globally. Furthermore, all of the problem cases were from the 1980s or earlier, indicating that our grasp of the science and practice of biological translocations is improving. We’re getting good at this! There have also been many positive unintended consequences here: for example, the Eurasian hawk moth was introduced to the American West to combat the leafy spurge (considered a weed), but has since become the single most important pollinator for the endangered western prairie fringed orchid, helping stabilize its population in North Dakota. The note describing this is practically a prose poem:

“The Eurasian hawk moth species Hyles euphorbiae has been introduced at multiple sites throughout the western U.S. to control the invasive noxious weed leafy spurge (Euphorbia esula). After establishing at release sites in Montana and Canada, H. euphorbiae spread to eastern North Dakota, reaching the Sheyenne National Grasslands, home to the only remaining populations of the endangered western prairie fringed orchids (Platanthera praeclara) in the state. The western prairie fringed orchid has an obligatory mutualistic pollinator relationship co-evolved with indigenous hawk moths, but despite the Eurasian origins of H. euphorbiae, it has become the primary pollinator of western prairie fringed orchids in North Dakota (Fox et al., 2013). North Dakotan orchid populations are presently stable owing to the pollination of H. euphorbiae.”

-Novak et al., 2021.

Got that? A hawk moth was introduced to control the leafy spurge, an “invasive” plant species. Then the hawk moth became “invasive” itself, but turned out to become the primary pollinator keeping alive the last populations of the western fringe prairie orchid, an endangered native plant species!

I think this paper shows that conservationists should feel more free to take big swings, to be bolder and more creative in moving species around. Conservation translocations tend to work, and biological control agent introductions in the last few decades almost always work!

Nativeness is not binary—a graduated terminology for native and non-native species in the Anthropocene

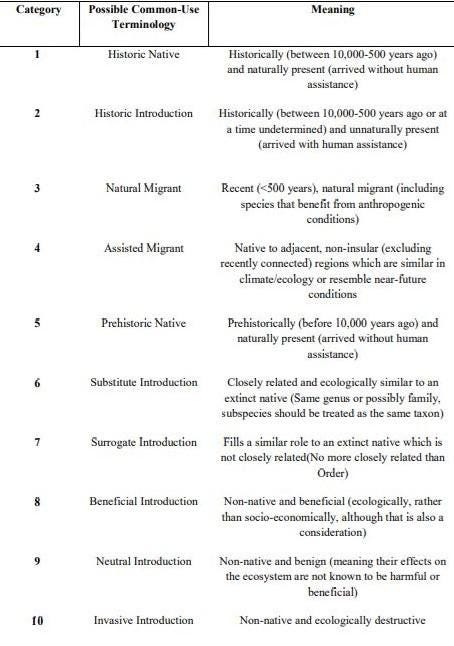

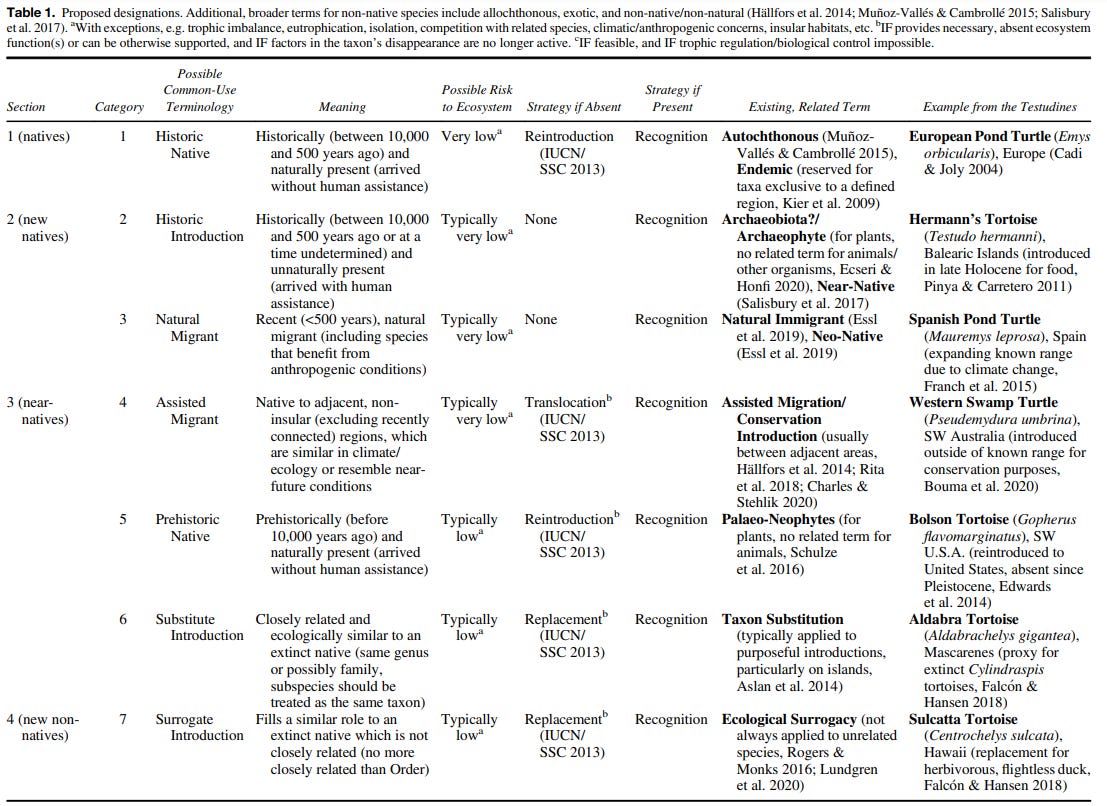

A recent paper coauthored by Rhys Lemoine in Restoration Ecology presents a new “species spectrum” to replace the old “native/invasive” binary, better way of thinking about these complexities.

The new paper offers a ten-category spectrum of descriptive terms to replace the "native" vs "invasive" paradigm, from "historic native" through "assisted migrant," "surrogate introduction," and "beneficial introduction", to the final category of "invasive introduction," calling for limiting that terminology to species where there's actual evidence of ecological destructiveness.

This really deserves to catch on-there are so many potential uses to describe current and near-future novel ecosystems and species interactions. "Historic introduction" covers "classic" reintroduction cases like wolves in Yellowstone, "assisted migrant" describes cases like the oyamel fir planting in Mexico, "surrogate introduction" seems like a good way to describe many rewilding projects (and hopefully soon de-extincted species as well!), "neutral introduction" describes many "invasives" (like the unfairly maligned purple loosestrife), and "invasive introduction" can be reserved for the few seriously damaging cases, like rats on small islands or the brown tree snake in Guam.

This paper is a worthy addition to the emerging conservation movement working to protect the Earth as it is, not as we'd like it to be. In the Anthropocene, we need to protect endangered species and productive, diverse ecosystems wherever we find them, no matter where they're from.

Also, Everything Emma Marris Has Ever Written

Emma Marris is likely the single best general-audience writer covering these topics. A good place to start with her oeuvre would be her under-covered book Wild Souls and/or her many excellent articles for The Atlantic! (One of her recent gems summarizes a study finding introduced and native large herbivores have similar ecosystem effects worldwide with the brilliant title “Nature doesn’t care where a species is from.”). Here’s this newsletter’s review of Wild Souls.

More Examples, From This Newsletter’s Archives

Doing the Donkey Work for the Whole Ecosystem

The feral horses and donkeys in America's desert Southwest are a controversial issue. They are descendants of escapees from colonial Spanish settlements, and so many people regard them as an invasive species: the US Bureau of Land Management removes some from public lands every year, and is currently keeping thousands in corrals. However, these equids have also been here for hundreds of years by now, and as "mustangs" are a key facet of the culture of the American West. Furthermore, horses actually evolved in North America to start with, eventually dispersing to other parts of the world, and the last "original" North American wild horses were only extirpated at the end of the last Ice Age, a little over 10,000 years ago. That's a mere eyeblink in evolutionary time.

Now, a recent study has found that these “invasive” horses and donkeys of the American West are actually key ecosystem engineers, supporting a multitude of other species. Camera traps in four locations across the Sonoran and Mojave Deserts of California and Arizona revealed that the wild equids routinely dig wells with their snouts and hooves in areas where there is no nearby water source, sometimes going six feet (2 meters) deep to reach the water table! This reduces the distance between water sources greatly, helping the whole ecosystem by increasing the amount of water available. The camera traps directly observed these equid-dug wells being drunk from by no less than 57 local vertebrate species, including black bears, mule deer, javelinas, bobcats, American badgers, scrub jays, toads, and the rare and unique elf owl, the smallest owl in the world. Eventually, abandoned equid wells become nurseries for young cottonwood trees as well.

These aren't a sideshow either: equid wells increased water density relative to "background" water by an average of 332%, and at one site, when a stream dried up, were providing all available surface water to the local wildlife. Equid wells' ability to buffer the local availability of water will likely be key in helping these dryland ecosystems adapt to climate change.

This is another spectacular example of "out-of-place" species, that don't fit the idea of what is "natural" to a region, turning out to be a critical benefit to the local ecosystem! Great news.

Kestrels, Geckos, and Ravenalas, Oh My

The Mauritius kestrel came to the edge of extinction in 1974, when only four individuals were left after decades of losses to DDT and feral cats. A robust captive breeding program3 brought their population back from the brink to over 800 free-living birds by 2010. Now, their numbers have declined again, to perhaps 350 individuals, as habitat destruction lowered the population of their gecko prey.

Interestingly, the fan-like “traveler’s palm” ravenala trees, native to Madagascar and introduced to Mauritius, have become a key support to help the remaining raptor population thrive again. (This writer particularly loves the ravenala trees as a species after seeing their vital role as a keystone species firsthand in the Malagasy rainforest). Insects love their nectar and fruits, and geckos love the insects, colonizing ravenala trees en masse. Geckos now provide up to 70% of the kestrels’ diet, and kestrel nests surrounded by ravenalas produced more fledglings.

Arachnids in the U.S.A

The jorō spider, Trichonephila clavata (pictured), is a charming, brightly colored little arachnid native to East Asia, associated with mythical shapeshifters in Japanese folklore. In the early 2010s, they were accidentally introduced to the Atlanta, Georgia area, likely via a shipping container. Since then, the species has proliferated and become common in northern Georgia and the Carolinas, with individuals seen as far afield as Tennessee and Oklahoma. These spiders spin their wide yellow-tinted webs very high in the tree canopy, an ecological niche that's not common among North American spiders, which may have contributed to their success. These spiders also practice "ballooning," using their silk to ride the wind to new locations (as made famous by the end of Charlotte's Web) so they can expand their range very quickly. Now, a new study from University of Georgia ecologists found that jorō spiders can tolerate below-freezing temperatures due to their rapid metabolism, indicating that they may well eventually survive and thrive as far north as New England.

Fortunately, there's no evidence that the jorō spider is having any negative impact on native species, so this isn't particularly worrisome. They're also harmless to humans; their fangs are so short that they can't even break our skin. “People should try to learn to live with them,” said study coauthor Andy Davis. “If they’re literally in your way, I can see taking a web down and moving them to the side, but they’re just going to be back next year.” (Finally, someone trying to nip “invasive species” hysteria in the bud before it starts!)

A follow-up study from Davis confirmed that the joro spiders aren’t outcompeting native species, and seem to be unusually good at building webs on human structures like power lines, stoplights and gas stations.

Happily, all this might well have a net positive ecological effect, as jorō spiders have been observed eating the brown marmorated stink bug, a serious agricultural pest (also introduced from East Asia) that caused $37 million in damages to apple crops in 2010 alone. Jorō spiders are one of the few spiders that will eat brown marmorated stink bugs, so their advent may well be a boon to American agriculture. Plus, they're beautiful; natural Halloween decorations, as one entomologist described them. A new American "immigrant species"!

Spotted Lanternflies: Basically Harmless

With the jorō spiders, researchers worked to nip “invasive” hysteria in the bud. An emerging parallel research area is “debunking” previously established myths of deadly invasiveness, often based on hearsay or xenophobia rather than biological evidence. For example, the spotted lanternfly, a sap-feeding “invasive” insect species that arrived from China in 2012, was recently publicly and widely feared as a potential threat to America’s hardwood trees, with extensive yet unsuccessful eradication campaigns enacted. Now, new research has found that they do not appear to be a serious threat to hardwood trees, with experiments testing a “worst-case scenario” in which spotted lanternflies fed on the same trees for four consecutive growing seasons resulting in zero trees dying. Yet another example of invasive species turning out to be harmless!

Wildlife Biology’s Next Big Paradigm Shift Is Struggling To Be Born

What do all of these new papers have in common? They’re engaging with biological reality first and foremost, looking at the facts on the ground instead of filtering everything through human-conceived lenses of “nativeness” and “invasiveness.” Young biologists (and open-minded older ones) are creating a new discipline, the study of introduced species’ effects on the broader ecosystem without the inherently prejudicial “invasive species biology” framework. I’m calling this “immigrant species biology,” and this article is my attempt to popularize the term and chronicle some great recent publications in the nascent field. May it spread and prosper!

What a great article! So much great information! I love the gradient of 10 labels describing introductions. I will be diving into these source papers for research for the book I'm co-authoring. Thanks so much for posting this. I am subscribed and looking forward to reading more.

Your writing is brilliant! And as an artist whose work combines scientific data with images and text researched from archival sources, this week’s series is perfectly in synch with my current project, developing a series on the early modern roots of biodiversity loss (as a artist research fellow at the Folger Shakespeare Library) I just love the new terminology suggested and will begin using right away as I discuss my work.