This is my first article reporting in-person from Mexico! It covers my visit to the field sites of Dr. Cuauhtémoc Sáenz-Romero, who’s working to safeguard the future of the monarch butterfly in a changing climate by planting seedlings of their favored winter hibernation tree (Abies religiosa, the oyamel or sacred fir) at higher, cooler altitudes. Here’s this proactive research project’s online donation link.

For background and context, check out the interview with Dr. Sáenz-Romero I published in November 2024 and my brief note on arriving in Mexico in early 2025.

¡Disfruta leyendo!

On the morning of January 30, 2025, I rendezvoused with Dr. Cuauhtémoc Sáenz-Romero in the charming little town of Angangueo on the edge of the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve (MBBR). I had previously published an interview with Dr. Sáenz-Romero in November 2024, but that had been conducted over Zoom: this, just a few days after my arrival in Mexico, was our first in-person meeting. We were a party of five that day, joined by a graduate student, a postdoc, and another curious American.

Our first stop was a site where Dr. Sáenz-Romero and his team had planted “nurse plant” shrub species recently, at an elevation higher than existing sacred fir groves and monarch butterfly hibernation colonies but on the same mountain within the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve. The very concept of beginning a reforestation project with nurse plants was controversial in Mexican forestry and represented Dr. Sáenz-Romero “pushing the envelope,” so to speak, as part of the recent global wave of research findings (perhaps most famously including Suzanne Simard’s Wood Wide Web) that indicate many plant species can exchange nutrients underground and otherwise cooperate to help each other grow, with interspecies competition a common but not universal paradigm.

Dr. Sáenz-Romero referred to his planting of the nurse shrubs as “imitating ecological succession,” helping speed up the process that would allow new sacred firs to grow. He gave the context that the Mexican forestry field had historically dominated by the cultivation of pine trees for timber, and that pine trees were a shade-intolerant genus that would not benefit from nurse plants like the shade-tolerant sacred firs, leading to most established foresters viewing all shrub species as mere competition for pines and helping to explain the institutional resistance to his research proposals. But in the age of climate change, nurse shrubs are increasingly vital to shelter young oyamel fir seedlings from wildly swinging extremes of heat and cold, making them a central part of moving the fir forests.

As we drove into the reserve, As we drove into the reserve, we passed stands of Pinus pseudostrobus, one of a medley of pine species destined to be supplanted by Abies religiosa as we attained higher altitudes. Dr. Sáenz-Romero explained that the MBBR’s land tenure system was highly complex, with long and narrow parallel strips of forest ownership (or rather, usufruct rights) by local ejido communities overlapping with state and federal authorities to form a social and legal web that he had to carefully navigate.

At this site, Dr. Sáenz-Romero hoped to plant Abies religiosa seedlings, the sacred oyamel fir, under the protection of these nurse plants. We were to check how they were getting on and record their survival rate, height and canopy diameter. Classic environmental science fieldwork, reminiscent of my university days, as deployed in the service of a boldly proactive assisted-migration climate resilience conservation project. I couldn’t wait.

We rented horses after parking near a reserve entrance (each horse came equipped with a classic vaquero-style Mexican horned saddle that wouldn’t have been out of place in 1500s New Spain!) and local guides led us up the mountainside.

We soon arrived at the site, a extra-large clearing of broken trees, shrubs, and grasses. It stood at an elevation of 3,400 meters, higher than A. religiosa was historically thought to climb on this mountain. Thousands of trees in this area had succumbed to a ferocious winter storm in March 2016, and the relatively open space had been planted with nurse shrubs by the research team in July 2021. Dr. Saenz-Romero assured me that none of his forest-moving research had ever required any trees to be cut down: the frequency of hurricanes, wildfires, pest outbreaks and landslides in the area ensured a steady supply of freshly opened areas ready for new nurse shrubs and sacred fir seedlings to be planted

The research team fanned out and began to work, following paper plots of planting sites to measure the surviving shrubs’ vital statistics.

The two main nurse shrub species they had planted at this site were Baccharis conferta (known for some reason as Chinese brush even though it’s native to Mexico, and considered by Dr. Saenz-Romero to be the gold-standard nurse plant species) and Eupatorium glabratum (aka Ageratina glabrata). As Mexican forestry had hitherto disdained such shrubby species, this research team had had to determine the most basic facts of their biology from first principles, figuring out their seeding times and growth rates by trial and error while cultivating them at a nursery in the nearby Cerro Prieto ejido.

The work was interesting and convivial, but stooping to take precise measurements became fatiguing after a few hours. During a lunch break in the field, Dr. Sáenz-Romero, an excellent raconteur, told us about his namesake. The original Cuauhtémoc (“Descending Eagle” in Nahuatl), was the eleventh tlatoani of Tenochtitlan and the last Aztec Emperor1. He had fought in the losing battle to defend his people from the conquest by Hernan Cortes’ brutal war-band of pox-spreading marauders in 1521, but was captured and held as a hostage by the Spaniards for four years. In 1525, on the orders of Cortes, Cuauhtémoc was killed secretly by being hung by his feet from a tree and letting his blood rush out through his cut throat. Oral tradition holds that his bones were recovered by the local people and secretly hid in a place of honor as a symbol of indigenous resistance. This was dismissed as a legend, but in the 1940s and 1950s, a new generation of archaeologists started investigating these stories and eventually rediscovered the bones of an early-1500s adult indigenous man who would have matched Cuauhtémoc’s known description in a location that oral tradition had suggested. In 1962, Dr. Saenz-Romero was born, and his father, impressed by this history, named him Cuauhtémoc. This year, 2025, will be the five-hundred-year anniversary of the original Cuauhtémoc’s death.

My kind scientific host also mentioned that he’d once briefly met Claudia Sheinbaum, the current President of Mexico, when they were both environmental science students at different universities, and paid this writer the profound compliment of saying that he, Dr. Sáenz-Romero, had been interviewed by several media outlets about this project but found my interview to be the best and most comprehensive that he’d ever done.

By late afternoon, the team had finished measuring the nurse plants’ progress. If all goes well and negotiators with local land managers come to fruition, Dr. Sáenz-Romero plans to plant sacred fir seedlings under this MBBR site’s sheltering shrubs in July 2026!

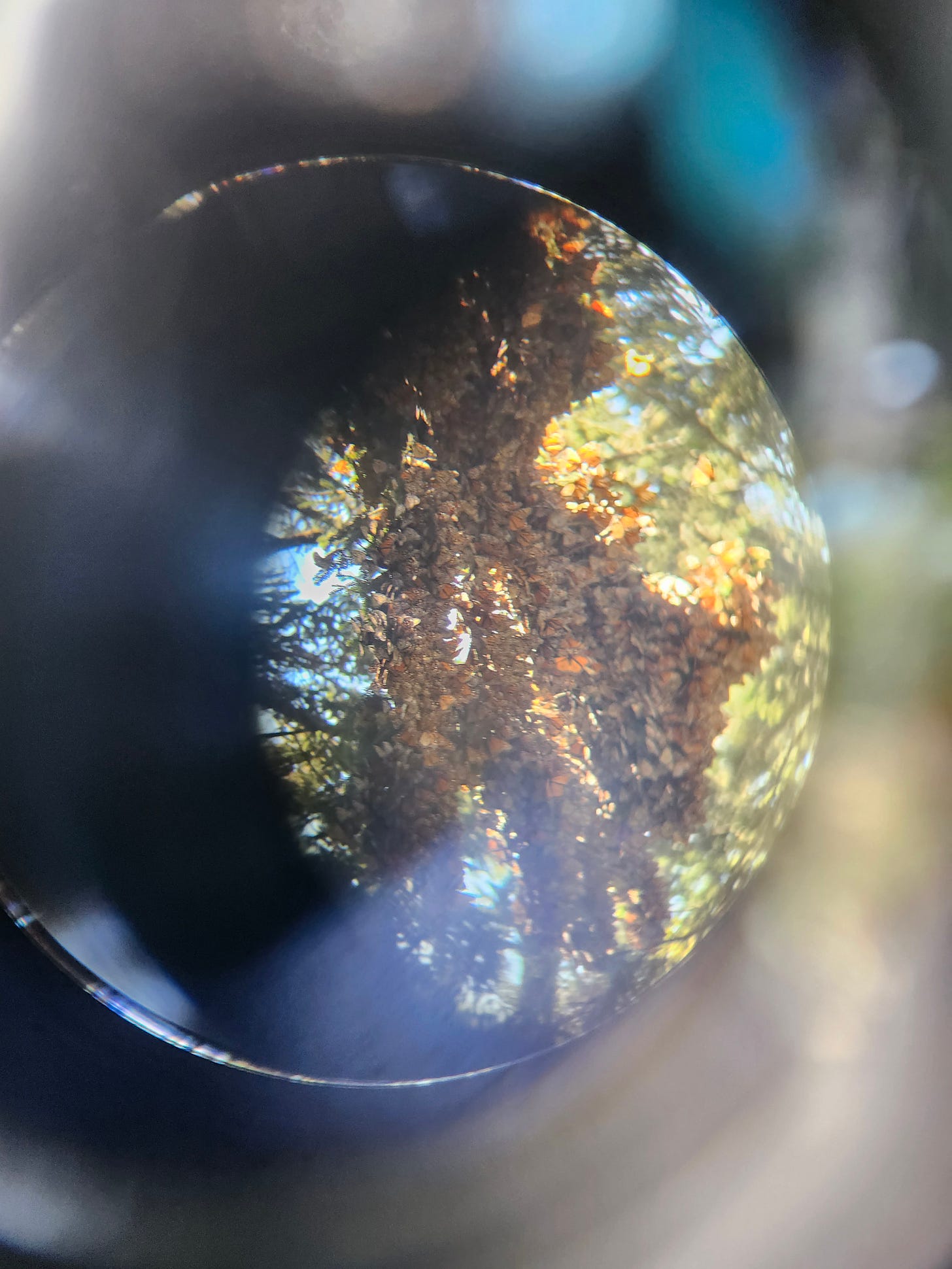

Then came the reward, the reminder of why we were doing this work: a quick stroll down the side of the mountain to see this winter’s colony of hibernating monarchs in majestic adult Abies religiosa trees.

It was one of the most stupendous efflorescences of biological richness that I had ever seen, reminding me of the flamingoes of Navi Mumbai and the chital deer of Nagarahole in its sheer shocking splendor. Thick as leaves, the branches themselves bowed under the weight of the monarch multitudes.

Beautiful black-and-white-and-orange butterflies crowded the trees to a positively implausibleextent; the bodies of their dead paved the trail and living stragglers paused on seemingly every leaf and flower.

There were so many individual butterfly wingbeats that they were collectively audible as a beautiful all-encompassing sound, like soft summer rain or a whispering thunderclap.

I’d heard the historic mega-flocks of American passenger pigeons (possibly to be de-extincted soon!) described as a “biological storm” – these monarchs seemed like a “biological breeze,” a refreshing omnipresence enriching the air itself with vivid life.

I was thrilled and honored to have seen them.

After a drive away from the reserve towards the second major planting area on the Nevado de Toluca volcano and a night in a hotel near Toluca, I began the next day with an interview Dr. Sáenz-Romero had kindly arranged. I was to speak with the elected leader of Calimaya, a local community of the Matlatzinca indigenous people that owned a large swathe of forest in the Nevado de Toluca region.

Interview with Jose Luis Malvais Rios, Presidente de Bienes Comunales de Calimaya

This is a transcription of an interview conducted in January 2025 in Calimaya, Mexico. In this interview (unlike the rest of this missive), this writer’s questions and comments are in bold, Presidente Malvais Rios’s words are in regular text, and extra clarification (links, etc) added after the interview are in bold italics or footnotes.

Thank you for meeting with me, Señor Presidente.

It is an honor that you are here.

We are fortunate to have 3,800 hectares of forest, in relatively good shape. I have always been interested in the environment, and it is relevant for the issue of freshwater supply. The provision of fresh water is linked to the status of the forest. The key part is the capacity of the forest and of the alpine grasslands to filter water through to the subsoil, so it becomes groundwater.

What changes have you noticed in the forest, over your life?

We have more forest pest outbreaks than ever. Descortezadores, bark beetles, Dendroctonus adjuntus. It’s something new, and it’s growing. We have done clear-cuttings of the beetle-ridden trees to contain them, but even so, pest attacks continue. Also the muerdago negro, mistletoe, a parasite plant. They’ve spread out, both the bark beetles and the mistletoe. And the forest fires. We’ve noticed how the springs of water have yielded less and less water.

One indication that things are different is the new pest outbreak, bark beetles at 3,800 meters of elevation. They’re higher than ever before, because it’s warmer now. That’s a really surprising elevation, it’s hard to believe that bark beetles are now at 3,800 meters. I asked a Mexico State University researcher, and he said it’s the highest ever.

The state government just provided a crew of 12 people to fight the spread of mistletoe for one year. They’re pruning the branches that host this plant, to contain it. That’s new.

What do you want? What does your community need to ensure the future of the forest in your care?

The priority is to raise the collective consciousness about environment problems and the supply of fresh water. Calimaya is doing better than its neighbors. They must improve.

I’m very proud of our new project. We’re establishing our first forest nursery! We do reforestation every year, but previously with seedlings from the state government. Soon we will produce our own seedlings with seeds from the local forest. The major species is Pinus hartwegii, the native timberline tree. Our goal is eventually 500,000 to 700,000 trees!

Great work! What kinds of animals live in your forests?

Wild turkey. Teporingo (the endangered Mexican volcano rabbit!). Vibora de cascabel, rattlesnakes. Camaleon. Venomous lagartija scorpions. Coyotes. Aguilas, eagles. Gato montes, bobcats. Deer. Zopilote, turkey vultures. Aguillillas, hawks. Tortolas (Columbide). Many species of hummingbirds. Chillones. Cenzontle, the mockingbird, that is rare. Calandrias, larks, many colors. Canarios, songbirds, many colors.

What other problems are you facing?

There’s a big problem with the commercial potato producers nearby in this region, their herbicides and pesticides are killing animals. They’re run by people not from our community, who are renting the land. There are now new factories to make chips from potatoes, for the Mexico City market. It’s a big business.

If you’re just renting the land, the incentives are different. Herbicides and pesticides can boost short-term profit, but you’re harming yourselves and you don’t realize it.

What do you dream of as a future for your community?

My largest excitement and source of pride would be if we were able to inherit a healthy forest for the coming generation. That the children and young people could go to the forest and see it, know what it means as a water supply. The ability to inherit a health forest is the work of several generations at Calimaya.

What else would you like to share about the work you’ve done?

I’m especially proud of the forest nursery. We obtained funding for that with Dr. Angel Endara-Agramont. The state government funded only two such nurseries in all of Mexico State, at Texcoco and here in Calimaya. I’m very proud.

I’d love to hear more about the nursery!

We dream of cultivating the trees that adapt best to climate change. Reforestation programs are more than planting, they need maintenance, they need to be protected from grazing and wildfires. We have a goal of producing 500,000 to 700,000 seedlings over the next three years, 2025 through 2028.

Awesome! How many people work there?

Two to three people are employed at this nursery permanently, but there are many more temporary staff.

This is fascinating; thank you so much for your time. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

We are proud and honored that the work of this community is known outside of the community thanks to your writing.

End of interview. First-person narrative reporting now resumes in normal text.

From Calimaya, we drove to the great volcano Nevado de Toluca. As we approached, it was a magnificent demonstration of the old ecological adage that in North America, increasing altitude recapitulates more-northernly latitudes.

As a geography and ecology-obsessed child, I’d read somewhere that if you climbed a high-enough mountain in Arizona, you’d experience in a day the same suite of ecosystems in the same order as you would if you walked thousands of miles north to Hudson Bay. Scrublands and semi-desert at the base, then deciduous woodland, then coniferous woodland similar to boreal forest, then above the treeline a stony tundra-analogue, then year-round snow and ice.

Here, at Nevado de Toluca, we were driving up the slopes of just such a “sky island” through our own fast-forwarded multi-biome journey. We passed by the prickly-pear cactus and agaves of the Mexican semidesert, past the classic local corn (maize) farms to the higher-altitude pesticide-using potato farms, interspersed with sharp artificial escarpments where sand and gravel had been mined out from under the fertile volcanic topsoil. We drove through stands of mature cypress that had been planted by old reforestation projects long ago, an abandoned Christmas tree farm with fir trees similar to those from my childhood New England holidays, and stands of Pinus montezumae, the noble Montezuma pine or ocote tree. Eventually, we wound our way up the mountainside and checked in on the planting site.

As in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, not a single tree had been cut to further Dr. Saenz-Romero’s assisted migration project, which continues to agilely adapt of newly created openings in the forest for planting sites. On Nevado de Toluca, it was not a storm but a phytosanitary clear-cut to prevent the spread of voracious bark beetles that had provided the grassy opening.

This site was at 3,800 meters elevation, 300 meters above what was traditionally considered Abies religiosa’s upper limit at 3,500 meters. It was heartening to see the young seedlings thriving in what was technically considered to be above their natural range,

Finishing fir seedling measurements didn’t take very long compared to the previous expanse of nurse plants, especially because most of the research team had begun early that morning while Dr. Sáenz-Romero and I lingered at Calimaya for the interview. After pauses to admire the beautiful vista over the Toluca valley, and a perplexing surprise or two typical of field work2, we had soon wrapped it up for the day.

My host then confided in me anew that one of the biggest obstacles to his work, even now preventing him from planting as many seedlings as were needed, was the persistent “eco-puritan” mindset leading some people in positions of influence to oppose planting sacred fir seedlings at any location where they had not been historically present — even just a few hundred meters up the slopes of the same mountain — out of concern for a nebulous human-imagined “purity” of the ecosystem. At a time when climate change was bringing unprecedented conditions here and everywhere else in the world, we shared our disgust for this counterproductive, and obstructionist belief system, still all-too-common in the world of wildlife conservation. On today’s Anthropocene Earth, essentially no species anywhere is a “native” species anymore in the sense of still living in the temperatures and conditions in which it evolved, and those who care for our cousins across Earth’s biosphere must remember that human-assisted migration is no longer any less “natural” than the alternative of leaving species in place in a warming ecosystem that’s stranger to them every year. With or without assisted migration, plants and animals will be learning to live in new conditions: the only question is whether we help them reach and/or create conditions where they can thrive.

On the way back down from Nevado de Toluca, we stopped the car and got out to observe a magnificent agave plant by the side of the road.

It was almost ready to flower, with its single magnificently gigantic flower-bearing spike-mast, not yet unfolded, rising for meters above the leaves. The genus agave, renowned icons of the North American deserts, are sometimes called “century plants” because they bloom just once in their long lifetimes and then die.

As I parted from Dr. Cuauhtémoc Sáenz-Romero and his team and took an impressively well-built intercity train line back to Mexico City, I looked at my phone and was deeply disturbed by the horrifying political news from my country of origin, but my recent experiences helped provide a psychological counter-force granted by a slightly broadened perspective. Humans aren’t just the thoughtless, unwitting cause of climate change; all over the world, unassuming land managers, community leaders, innovative scientists, and ordinary caring individuals are working to steward the ecosystems in their care and help them to survive the tumultuous Anthropocene. This sort of work rarely makes the news, goes viral, or commands headlines or social media feeds, but this pointillistic mosaic of local care-giving efforts all around the globe will help sustain Earth’s biosphere into the 2100s and beyond. I felt privileged to have seen this example.

These titles refer to the same person in most but not all cases. Even though every Aztec emperor was the tlatoani of Tenochtitlan, the home city of the Nahuatl-speaking Mexica people now commonly known as the Aztecs, not all tlatoanis of Tenochtitlan can be reasonably described as Aztec emperors. The first three tlatoanis of Tenochtitan were kings of just one city-state among many in the Valley of Mexico, with the “empire” status really arriving only with tlatoani #4 Itzcoatl. There were a few more tlatoanis after Cuauhtémoc, but they were just metropolitan-level puppets of the ruling Spanish empire.

The research team had previously set pollen traps at this Nevado de Toluca site, bearing cotton to absorb drifting plant gametes, but the traps were now cotton-less and data-less; the general consensus was that birds had probably taken it to use in their nests.

So amazing

Hi Sam, this is such a wonderful piece. Thanks for sharing the dispatch. It's amazing to see "assisted migration" in action.

Reading your story, I thought of this wonderful essay by David Abram in Emergence Magazine. The migratory magic of the monarch butterfly is featured here:

https://emergencemagazine.org/essay/creaturely-migrations-breathing-planet/

"Four generations removed from those who last journeyed south, they will wing their way over mountains and spreading suburbs and dammed-up rivers, roosting in maples and pines, only to push south afresh the next morning, ultimately zeroing in on the very same few acres of conifers in the Mexican highlands—perhaps even the very same tree—to cluster with a hundred million other monarchs through the winter.... How does an organism inherit such intricate instructions—precise navigational guidance that must be different for each successive generation?"