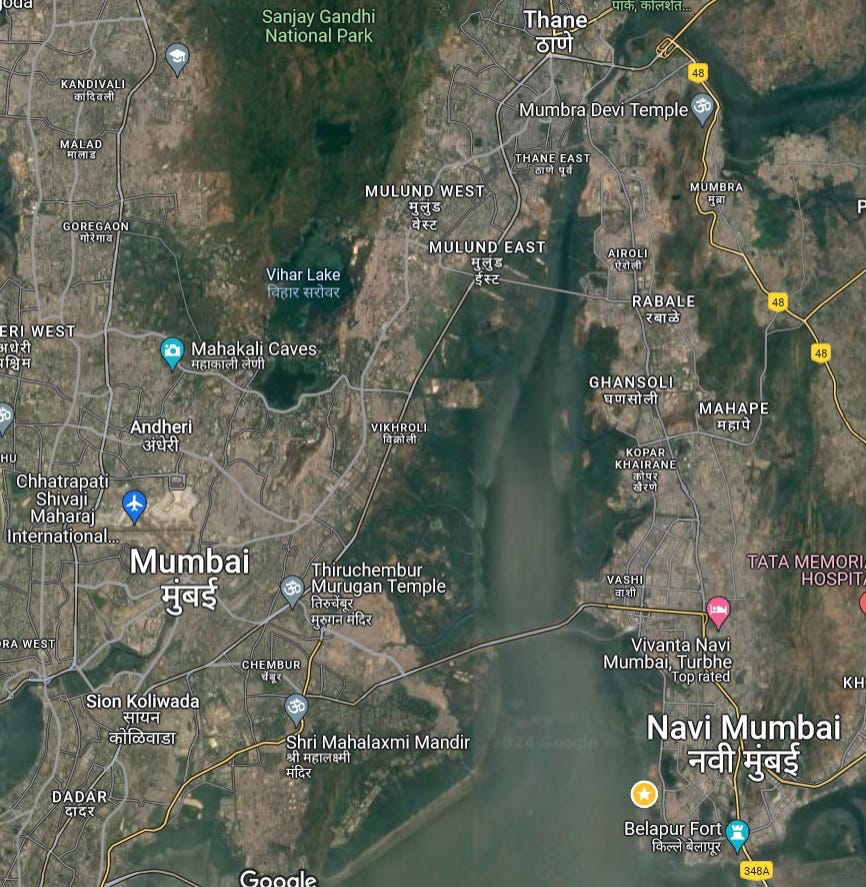

After the Sanjay Gandhi National Park hike, I spent two days essentially “crashing,” recovering from a series of thrilling but hectically eventful days by sleeping in my hostel for long periods and eating at a few local restaurants and cafes in the Marol Maroshi neighborhood. Thus refreshed, I woke up early again on Friday May 10th, catching a motor rickshaw to go see Navi Mumbai’s famous flamingos1. I had read of the seasonal presence of a flock of lesser flamingos (Phoeniconaias minor) in the excellent Hakai magazine. Starting with early flamingo visits to the nutrient and algae-rich mud flats of the Thane Creek area in the 1990s, the population kept growing as more flamingos found the urban estuary life congenial, reaching 10,000 in 2007 and an estimated 130,000 in 2022! And there are good signs for long-term sustainability as many Mumbaikars have embraced their new visitors, with an annual Run for Flamingos event attracting thousands and mobilizing a conservation-wise community.

I very much wanted to see this excellent example of human/wildlife coexistence, but at first I wasn’t sure I’d be able to on this trip. The reports I’d read said that they arrived for the winter, and it was now May: I wasn’t sure if they had stayed in their Mumbai feeding grounds or had already returned to their breeding grounds in the salt deserts of Gujarat. Since arriving, I’d heard in person that they’d been in the city as of February 2024, but my informant didn’t know if they were there now and online searching wasn’t helpful. Then, a stroke of luck: Vaibhav (my naturalist guide at SGNP) happened to tell me that he’d taken an iNaturalist photo of some flamingos just a week ago. He sent me a Google Maps reference upon request, and the trip was a go!

The trail Vaibhav recommended explored the thin mangrove-and-mud-flats semi-wild fringe of Navi Mumbai, specifically the part around the outskirts of T. S. Chanakya, a local “maritime college” that reminded me a bit of the renowned Maine Maritime Academy in Castine. As I started walking, I saw an abundance of colorful flamingo-themed graffiti (seemingly official or at least approved) and several illustrated signs explaining flamingo facts, like how the mid-leg joint that looks like a backwards “knee” is actually morphologically their ankle, with their knee tucked up invisibly in their feathers. Already a good sign (literally) for coexistence!

Soon enough, I turned a corner and saw a trio of flamingos in a little micro-inlet of shoreline, accompanied by a beautiful pink-legged, white-chested black-winged stilt (Himantopus himantopus). I could clearly see that the “pink-ification” had progressed to different levels in different individual flamingos: many appeared almost all-white with perhaps a few gray patches, some had mere patches with barely visible hints of pink, and a few appeared mostly pink. (Flamingos get the pink color in their feathers from the carotenoids in the algae and brine shrimp they eat).

I admired these first flamingos of the day, snapped photos, and continued walking. I took a few little side trails into the mangroves, and was rewarded with the sight of flowering “holly mangrove” shrubs, an interesting network of semi-abandoned huts, boats, and simple foot bridges, and a magnificent white egret. There was unfortuantely plastic trash scattered throughout the landward fringe of the mangroves, true, but this was clearly still a landscape vibrant with life.

It was around this time that I saw frenzied movement on a low mud bank out of the corner of my eye, instantly halting as my shadow drew near. I froze, being careful to prevent my shadow from falling over the mud bank in question, and started vigorously eyeballing the area in anticipation. I was soon rewarded by the sight of tentative foreclaws peeping out of holes, followed by cautious scuttles as bolder individuals resumed their pre-startlement business. Fiddler crabs! The sight of the spunky little claw-bearers put a broad smile on my face.

But eventually I urged myself on: the sun was still rising, the morning was getting hot, and I had seen only a single-digit number of flamingos so far today. Even if most of the flock had already left for Gujarat, there would surely be more than that somewhere around here. After a brief improvisational parkour exercise involving a concrete wall, a metal staircase, a gap between trees, and the avoidance of several rolls of barbed wire2, I levered myself onto a sort of boardwalk heading seaward, which Vaibhav had recommended as the best place from which to see flamingos. I endeavored to manage my expectations as I reached the viewing-point terminus: I would be more than happy to see dozens, perhaps even hundreds if I was lucky.

And then…well, then, I arrived.

There were a lot of flamingos! Straight ahead, I could see hundreds just in my narrow not-quite-at-the-view-point field of view, with the hills of Sanjay Gandhi National Park rising in the background.

Really quite a lot of flamingos.

And, oh, look…there were even more flamingos in the other direction!

As I kept turning my head, there were simply more and more flamingos visible. A vast undulating plain of flamingos, all busily bobbing their heads down to feed. The mud flats were dotted with pinkish-white as far as the eye could see up and down the coastline. Every so often a few would take off and fly to some other spot. The tidal landscape with its seeming infinitude of little channels leading to the sea reminded me of playing on Massachusetts’ Crane Beach with my brother as a child, but this was a Crane Beach-style coast crossed with an African safari-level wildlife experience, a gigantic flock of waterbirds spread out before me. And it was all offshore to one of the biggest cities in the world. This kind of thing is exactly why I’m so optimistic about human/wildlife coexistence in the Anthropocene!

After goggling at this magnificent flamingo superabundance to my heart’s content, I descended a rickety rope-banistered staircase to inspect the mud flats in person, attracted by subtle popping sounds and barely-visible gleams as tiny shapes shifted in the sunlight. The entire mud flat was alive, with umpteen thousand tiny crabs (not fiddlers this time), tiny snails, and other invertebrates moving around the moist-lands. I knew that flamingos mostly ate algae, but they had to be feasting on all these little guys too: the mud was practically carpeted with available protein! Awesome.

I also noticed something rather odd. There were relatively few humans in my field of view (not counting the mega-city-scape on the horizon, of course), but there were a few small boats anchored in the flamingo-zone, and a few humans who seemed to be regularly going in and out of the little brackish channels through the mud flats. But they weren’t using the boats, they were progressing on their hands and knees for hundreds of meters through the mud, painstakingly pushing some kind of plastic-box contraption ahead, before squeezing and compressing the box at a designated location on the shoreline. This process continued over and over for as long as I was there and had the unhurried yet committed air of something that could go on for hours and hours. I still have no idea who these folks were or why they were doing this; I couldn’t see any visible product of their labor. Maybe they were sieving for some small crustaceans or something?

Eventually, the heat escalating, I decided to turn back. After a brief out-and-back attempt to “cut” across college grounds to the main road (the security guards were kind and shared their water, while politely but firmly expelling me from the grounds), I ended up retracing my steps on the same trail I’d taken to get here. More pleasant surprises were in store: by the time I reached the spot where I’d first seen a few flamingos today, a much larger group had settled in!

After that, as I neared the point where I’d started on the trail, I saw that even the little cove I’d passed at the start of the hike, then flamingo-free, had become the sight of a busy…gaggle? Okay, I just googled this, a delightfully named flamboyance of flamingos had taken up residence, with more flying in from the outer mud flats every thirty seconds or so. Perhaps they were seeking some measure of shade, or at least the proximity of shade-giving trees for the near future, as the day grew hotter.

The visual of the flamingos flying just a few hundred meters from a modern apartment block remains etched into my brain as a classic exemplar of the “New Wild.” As has been discussed in the writings of Emma Marris, Annalee Newitz, Kim Stanley Robinson, and so many more, entirely new ecosystems are forming at the intersection and intermingling of wildlands with heavily developed human-dominated population centers. The fact that such a vista exists in heavily-populated Mumbai, in a rapidly-developing country, seems to me not just a beacon but a lighthouse of hope for the future of humans, animals, and our world.

After leaving the coastal flamingo-rich areas, I started walking in the general direction of the Navi Mumbai bus stop where I’d reserved a ticket to Bengaluru, still with my full travel “inventory” on my back. A brief digression led me to an unexpected pleasure with potential socioeconomic relevance: I saw a local ice cream place with 4.9 stars on Google Maps, and decided to stop there. It was…really really really good ice cream. Silky, melt-in-the-mouth, flavorful…very possibly the best I’ve ever tasted (and I’ve tasted a lot of ice cream). I ordered one scoop of one flavor thinking it would be a light treat, and ended up staying for four scoops from four different flavors, including some surprisingly niche ones like “hazelnut.” The ice cream was just that good. And this estimation is me discounting for the heat and tiredness “hunger is the best sauce” factor; I’m pretty confident that if there was an ice cream place this good near where I lived, I would be going there all the time. I told the owners so, and they said the ice cream-maker who had taught them had trained in Canada and Italy.

This ice cream shop was in a fairly ordinary Navi Mumbai thoroughfare, not a gated community of the wealthy or a tourist-oriented area. I was the only visible foreigner I’d see all day. This ice cream business was staying afloat, and by all appearances doing well, selling to local customers. It may seem unexceptional today, but historically speaking, it’s a testament to the mass affluence of our modern technologically advanced global economy. In the 1700s, Voltaire and Thomas Jefferson had viewed ice cream as an absolute top-shelf luxury, an aristocratic privilege chilled with actual ice and made from hand-churned cream. Now, there was ice cream at least as good as that available in the salons of 1770s Paris (probably much better given a few centuries’ advances in technique, refrigeration, and flavor innovation!) on sale for a little more than one U.S. dollar to folks in Navi Mumbai.

A bare thirty minutes’ walk from piles of plastic trash and people pushing through mud flats on their knees, there was world-class ice cream available at a price reasonably affordable for the burgeoning Indian middle class. And, of course, that mud flat wasn’t some wasteland, it was vibrantly alive, a feeding site for thousands and thousands of migratory birds. That’s a very tangible instance of civilizational progress.

The sleeper bus ride from Navi Mumbai to Bengaluru (aka Bangalore) took about 20 hours, 24 if you count the four hours endeavoring to locate and then waiting in the general vicinity of the Juinagar Station bus stop. While waiting, I was lucky enough to fall in with a fellow passenger-to-be named Mahesh, who first explained how and why the bus was late and later furnished interesting conversation on the journey. As night fall, I was also surprised to see gigantic bats emerging from the scattered urban trees. The pictures above don’t do them justice: they were far larger than any bat I’d seen in America or Europe, undoubtedly flying foxes. This was in the middle of a city; the megabat population’s survival would seem to be a good sign that fruit and/or insect availability remains relatively high.

Eventually, the sleeper bus finally arrived and we piled in.

I awoke the next day as we rolled along the highways of Karnataka, pausing for a brief breakfast at a truck-stop kind of place where I tasted a masala dosa for the first time. After returning to the bus, Mahesh told me that he was from a farming family in the state of Andhra Pradesh, and regularly spent six months working in Mumbai before heading back home to help on the farm for the other half of the year. He talked about how expensive it would be to pay for new power lines to connect his farm to the grid, and how the prospects of their recent investment in 3 acres of newly-planted mango trees was dependent on future water availability. As variegated fields rolled by (the landscape rather reminded me of California’s Central Valley), Mahesh pointed out the corn, rice, palm trees, and other crops being grown. I didn’t recognize some of the other crops, and Mahesh told me that I was seeing areca nut farming. Growing fields were interspersed with other activities: semi-industrialized poultry farming is also apparently becoming more common across India, as a growing middle class follows the Europe-America-China trajectory of wanting to eat more meat, but qualified by majority-Hindu India’s still entrenched anti-beef mores. (I personally hope that lingering pro-vegetarian cultural sentiments will eventually encourage India to become an early adopter of lab-grown “clean” meat). There was even a fascinating small-scale “civic industry” of people making bricks from clay, apparently by hand, with clay fields next to growing colossi of proto-bricks drying in the sun.

We finally arrived in Bengaluru in mid-afternoon, kicking off the Karnakata stage of my journey for real! More dispatches will follow.

Navi Mumbai, or New Mumbai, is right next to Mumbai, like how New Delhi is right next to Delhi. In American terms, it’s rather as if Oakland was called New San Francisco or Fort Worth was called New Dallas.

It was at this point that my much-worn hiking trousers were irrevocably torn asunder, motivating my eventual purchase of additional pants from a Bengaluru street merchant. I would eventually change into my hiking shorts the next morning, retrieving them from my backpack during the bus ride.

I came here for the What Were They Doing answer and I am very disappointed in you all. (Not in Sam. Sam is rad.)

Thank you, it was a lovely morning read. It reminded me of Aminatta Forna’s lovely book Happiness about urban foxes in London and so much more! I loved the pace and voice of discovery in this piece.