Interview with Dr. Cuauhtémoc Sáenz-Romero, Sacred Fir Forest Mover

Safeguarding the future of monarch butterflies by planting a new climate change-adapted overwintering habitat at higher elevation!

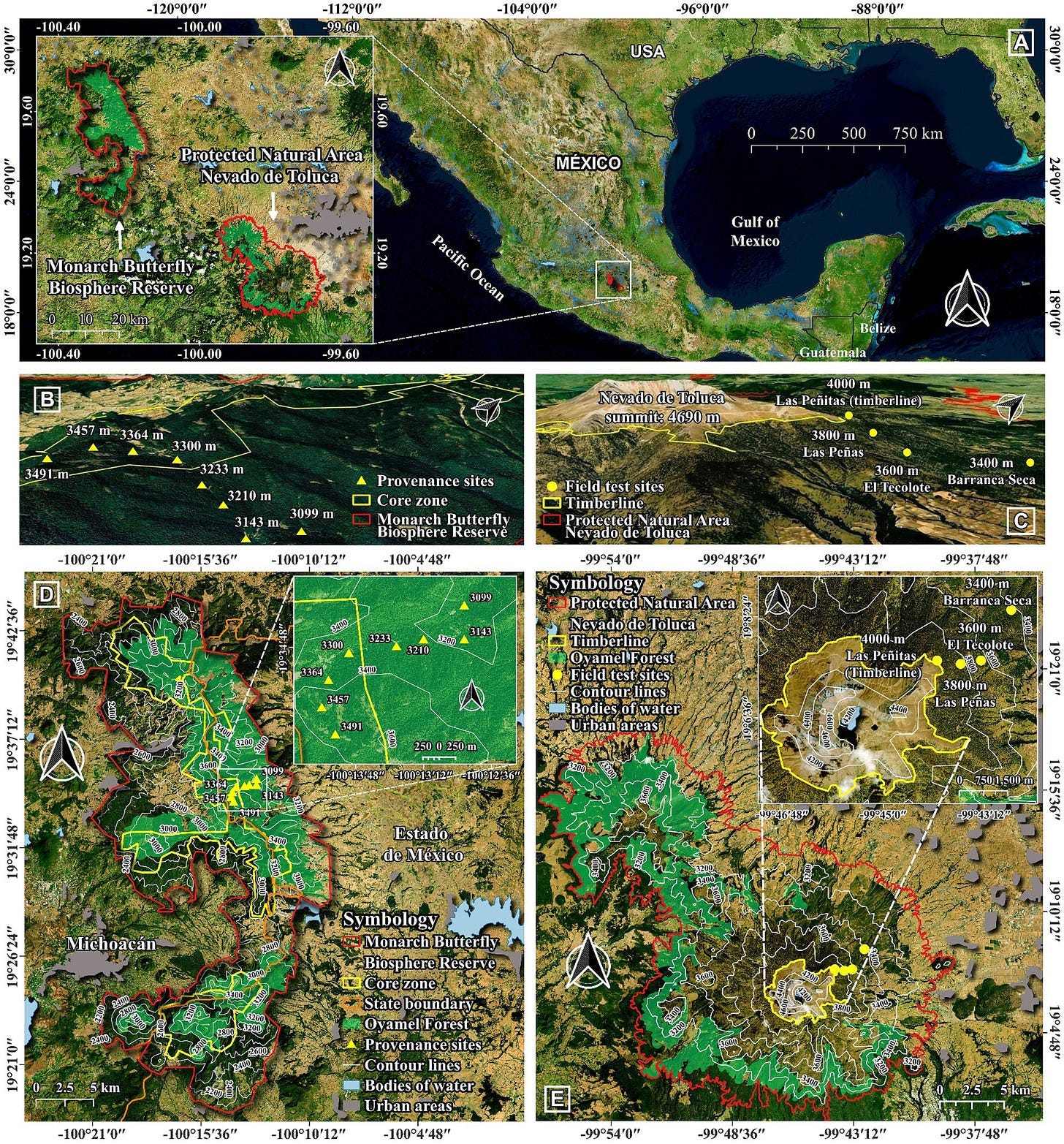

Dr. Cuauhtémoc1 Sáenz-Romero is an ecologist and forester, a professor at the Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo in Mexico. He’s leading a pioneering climate resilience conservation project: planting oyamel firs (Abies religiosa, aka “sacred firs”) at higher elevations than historically found to ensure consistent overwintering habitat for monarch butterflies as the world warms. They’re essentially “relocating a forest,” planting oyamel fir seedlings to create a new forest high on the slopes of dormant volcano Nevado de Toluca near Mexico City.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Dr. Sáenz-Romero’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

This interview is syndicated by both The Weekly Anthropocene and Your Daily Dose of Climate Hope.

Can you share your personal story? How did you get into ecology, and start this forest-moving project?

It has been a very long journey, Sam. In terms of background, I consider myself a kind of hybrid. My bachelor’s degree is in biology with a specialty in terrestrial ecosystem ecology, and then I did a Master’s in forestry at an agronomy university. It was kind of hard to be a biologist and an environmental agronomist, two professions that do not talk to each other enough. Sometimes they have opposite views. So I have an intermediate view about ecology and forestry.

Then, I got a Ph.D from the University of Wisconsin, Madison. I had an excellent advisor who had a very open mind, and suggested to me to explore the papers of Gerald Rehfeldt, a researcher from Moscow, Idaho. Rehfeldt had this approach of genetic ecology, studying differentiation of populations along altitudinal gradients. The Rocky Mountains are similar to the Sierra Madre Occidental of Mexico, and he suggested that his methods in the Rocky Mountains will apply to Mexico. He was right.

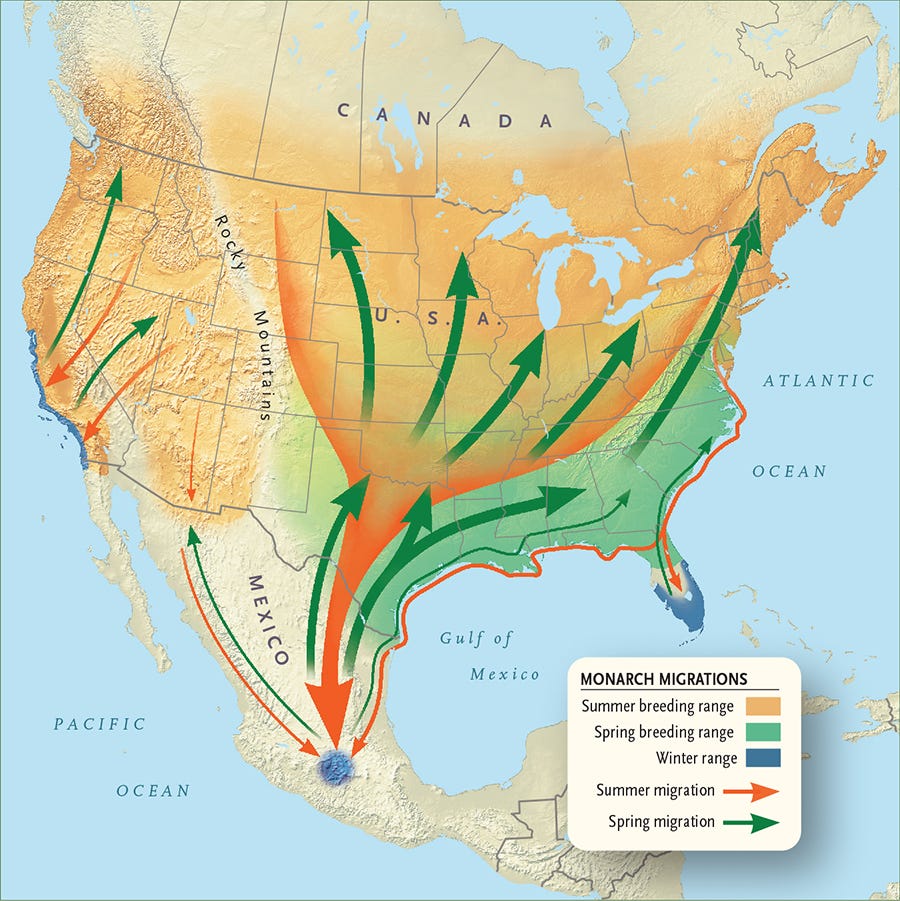

After finishing my Ph.D, I met by chance Dr. Rehfeldt in the Yucatan, in 2000. My approach was to study the genetic differentiation along altitude gradients. Not with molecular markers, but with quantitative traits, like bud elongation, frost damage, et cetera. In 2010, we published a paper in the Climatic Change journal (link) with a climatic model for Mexico. My mentor asked me, how can you apply this? We could use it with Abies religiosa, the iconic coevolution between the forests and the monarchs. It’s of trinational interest, Canada, the United States, and Mexico. So we made this modeling of the future suitable climatic habitat for Abies religiosa. That was the paper of 2012, in Forest Ecology (link). It gave a surprising result for me, a really shocking result, which was that the suitable climatic habitat for Abies religiosa may no longer occur in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve by end of the century. [This is a particularly big deal because oyamel firs are the key species that provides overwintering shelter to hibernating monarch butterfly colonies. Monarchs from across the continent all end up here for the winter, and losing their shelter trees would be a serious problem].

This was shocking because, as you know, Mexico has many, many problems: narco traffic, insecurity, deforestation, social inequality, poverty. And in that context, the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve is a case of success, with ecotourism an important source of income that has almost completely stopped illegal logging in the area - unusual in Mexico. But even for this case of success, I realized that even having this reserve that functions relatively well, the forest is going to be degraded, and probably disappear as we know it today, because of climate change. That was the thing that pushed me to try to do something different.

I associated with some colleagues, Roberto Lindig-Cisneros, coauthor of the forest ecology paper, and Arnulfo Blanco-Garcia, both coauthors of the Frontiers paper (link). From my studies of the ecology of genetic differentiation along altitudinal gradients, we had the idea of moving Abies religiosa seedlings upwards in the mountains, to higher elevations. So we’d collect seeds at the low elevations and plant them at the higher elevations, to prepare for climate change. These two colleagues work in ecological restoration, and they had the idea of the use of shrubs as nurse plants. So we planted two experiments using shrubs in 2015 and 2017, planting A. religiosa under the shade of the shrubs as nurse plants, which is described in the paper of 2019 (link).

And in the paper of 2012 for Forest Ecology, we had said that it is needed to increase the upper limit of A. religiosa to higher elevations to compensate for climate change. This meant that we’d need higher mountains that the ones in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, because their highest summit is at 3,500 meters, more or less, which is coincidental with the upper limit of Abies. Abies cannot move upward within the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve. [And with climate change, we’d need to move to elevations higher than the historic upper limit]. So we said, we should plan to plant at higher elevation on another volcano in Mexico. We said that in just two lines in the paper, and it survived the reviewers, so we figured we’d better do it!

It was very hard work. We collected seeds in 2017, produced seedlings for three years, and planted them in 2021, on Nevado de Toluca. We were very fortunate to have collaboration with a professor at the University of the State of Mexico, Angel Endara-Agramont, who suggested to me to plant in the community of Calimaya on the northeast slope of Nevado de Toluca. This is a community with native Indian origin, and that made a lot of difference. Many communities of Mexicans with native origin have, how to say this, cohesividad, cohesiveness. They are very well organized. They have a strong link with their territory. They work hard to preserve their forest. They work on planting and maintenance of our experiments, and they work extraordinarily very well, very hard, because they feel this attachment to their land. I feel very fortunate to be working with this community. Without this community, we would never be able to do what we have done.

As an academic, I’ve found that academics are very big on evaluation by publications. How many papers do you publish? That is your value as a person and as a researcher - if you don’t publish, you are dead as an academic. If you publish slow, you are a second-class academic. That is the system in Mexico - as well, as probably, the United States. But I know that no matter how many papers we publish, forest management is not going to change unless local people are convinced by what we’re doing. And we need to have a different forest management to respond to the challenge of climate change. How are we going to achieve that? By involving the local community. Most of the members of the local community are never going to read these papers. But when they see the results, they see that the seedlings are surviving, that is going to convince them. So we put a lot of emphasis on local participation.

Thank you so much! Can you tell me more about the role of nurse plants, providing shade and preventing water loss and extreme temperature swings? This is a great example of both mutualism and climate resilience. How do you pick the right species to use as a nurse plant?

This is a case where the community of ecologists and the community of foresters have not very close views. The role of the shrubs is well known in the books about ecological succession. If there is a forest fire or something and then regrowth, the herbs arrive first, then shrubs, then trees. That is well understood. But in the forestry practice, the shrubs are seen as marginal vegetation, nearly a weed. In my Master’s, they told me, if you’re going to do reforestation, say a commercial planting, you should prepare the site. And prepare the site means “get rid of the vegetation that was there.” Then plant the trees in a grid, say three by three meters. You have to get rid of the previous vegetation.

That is a mistake for a species that is tolerant to shade like Abies religiosa. And it’s a mistake because with climate change, you have more extremes of temperatures. The nurse plants, the shrubs, the bushes, always have been very important for the Abies religiosa, but now they are more important than ever, because we have more extreme temperatures. Before this role was important, now it’s vital, critical.

We also need to get rid of the things that we learned at the university about this planting in regular grids. In our second experiment at the Biosphere Reserve in 2017, we planted in circles, around the central stem of the nurse plant. I have to swim against the current of what we have learned in university. In university you have these engineering views of plants, they should be in lines, but we should get rid of that regularity and optimize the use of the shade of the shrubs. The shrubs, the nurse plants, are not distributed regularly. They are distributed randomly, or aggregated. So we have to plant in that way, and we did so on this new Nevado de Toluca experiment.

What are the most important species of nurse plants? Are some of them also nitrogen fixers? Which are the best species to use?

Baccharis conferta. Baccharis conferta is by far the best. We have some data that we haven’t formally published, where we have observed that Baccharis conferta is by far the best. It’s very resilient. It’s tolerant to drought, tolerant to frost, and the shade it provides is very dense. We have tested others, like Eupathorium glabratum and Senecio species, and these species are more damaged by frost, we have some mortality. We don’t have formal research published comparing three species, but it’s something we observe in the field, and it’s something that people tell us. Baccharis conferta is the best.

What are some difficulties you’ve dealt with in this project? Did you have issues with permitting?

We asked the question in our 2019 paper: Abies religiosa is very comfortable under the shade of Baccharis conferta. What happens if we do not have Baccharis conferta on the site? What happens on sites where we recently had a forest fire? Or another source of disturbance; there are many bark beetle outbreaks, and sometimes there’s a clear-cut to stop the increase of the bark beetle outbreaks. Then moving the logs destroys the remaining vegetation. So we thought, in these cases, we should plant Baccharis, to serve as a nurse plant for later seedlings. The problem we then had is that in the culture of the forest nursery in the region, 100% of nurseries produce either Abies religiosa or pines, Pinus pseudostrobus among others. Nobody produces a bush or a shrub, because, as I said, in the culture of forestry, these shrubs are kind of weeds.

So when we started, we couldn’t get them from nurseries, so we asked, “When should we collect the seeds of Baccharis?” We got vague answers – February, or March, or April, or May. There wasn’t accurate phenology information, so we couldn’t even find when to look for the seeds! We had a lot of prueba y error, trial and error, trying to figure out how to do it. We spent two years trying to collect seeds, and at the end, we decided to do asexual reproduction. We made cuttings of Baccharis branches, induced rooting, and produced clones in the nursery. That was one difficulty, the lack of culture to use the shrubs in the nursery.

Regarding the permits, we have had ups and downs. We had a very good Director of the Nevado de Toluca, who gave us the initial permits the start the experiments. But then after he left, we asked permits to do the assisted migration test of Baccharis conferta, and the permit was denied! On the grounds that the branches came from the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, and we would plant them in Nevado de Toluca. They told us that at sexual maturity, the pollen of the Baccharis we would plant may contaminate the existing population.

That is crazy! We’re seeing these same issues in America. It’s this very bio-conservative mindset that is not helpful.

Exactly. The argument was not, in my view, sustainable. First, at 4,000 meters, there is no Baccharis! Even at 3,800 meters, it’s nearly absent. And that’s exactly why we wanted to do assisted migration, to move the population upwards! At 3,400 and 3,600 meters, there is Baccharis. And besides, we’re bringing genotypes from lower elevations, if they spread out their alleles to the local population, it’s what they need, because we hypothesize that individuals from lower elevations have alleles that provide resistance to higher temperatures. And that will help them adapt to the future climate! We would be providing the local population with the alleles that they need to adapt! It’s a positive thing!

The permit was denied. And that made me realize how in Mexico, many people in conservation work have a very orthodox view, where Nature Should Be As It Is Originally, and we should keep that. But that’s impossible, to keep nature as we know it, because we have 420 parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere, and the norm is 280. [See the NASA page on this for more background].

Nature cannot act normally when you have 420 parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere. We have to do proactive management because we have destroyed the equilibrium of the planet! You have to do something about that and not just cross your arms and wait for nature to solve the problems. Nature cannot solve the problems in the short term with 420 ppm of CO2. Maybe in 10,000 years, yes, all the vegetation will be adapted by itself, but we don’t have 10,000 years. Climate change is too fast. It’s not just the amount of CO2 that we’ve pumped into the atmosphere that’s a problem, it’s the speed at which it’s changing. Natural mechanisms of adaptation are too slow to compensate. This disparity is the problem that we have to solve, at least partially.

“Nature cannot act normally when you have 420 parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere.

We have to do proactive management because we have destroyed the equilibrium of the planet!

You have to do something about that and not just cross your arms and wait for nature to solve the problems.”

-Dr. Cuauhtémoc Sáenz-Romero

I absolutely agree. This is a lot of what I try write about. Conservation can end up getting in its own way by preventing the proactive management we really need. Thank you so much for doing this work!

I worked with a reforestation project in Madagascar, and I found it really rewarding. What is a day in the life of this project like, on the ground? You go to Nevado de Toluca, are you carrying seedlings up by truck? Is there a road?

One of the major challenges is the funding. I’ve worked for the university for 25 years now. I don’t have a technician paid for by the university. I do not have access to an official vehicle. So I had to buy a Toyota Hilux pickup with personal credit. And it’s not 4x4, I need a 4x4 but I can’t afford that. So we move the seedlings in my personal vehicle, sometimes the vehicles of my students, and sometimes we need to rent a 4x4 if the rain destroys the dirt roads. That is a big problem. In Mexico, we have a lot of security problems, but fortunately, in this community of Calimaya, the community is very well organized and connected to the territory. We don’t have problems of insecurity at all in Calimaya, but that is something that you have to be aware of.

We collect seeds in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve. We collect seeds in the crowns, which is very difficult, because they are big trees. It’s dangerous work. We have to hire people that are good at climbing trees. We had a challenge in that we were producing the seedlings at Morellia. Morellia is at 1,900 meters of elevation. People told us, if you cultivate seedlings around that height, then plant the seedlings on Nevado de Toluca at 4,000 meters, all the seedlings are going to die from the temperature shock.

So we move the seedlings to a communitarian nursery at a different site in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, Ejido la Mesa, at 3,000 meters of elevation. The nursery is at the house of the ancient chief of the ejido, which is a communal system to own the land in Mexico. A man over seventy years old, with a lot of wisdom about the area. His name was Francisco Ramírez-Cruz, or “Don Pancho.” I had this dilemma, when I had some opinions about raising seedlings, and he said no, no, no, we do things this other way. I faced a choice, to tell this guy, “I’m paying, do it my way,” or to accept the fact that Don Pancho is 70 years old and knows this species better than me, and let him do many decisions of the seedling production. So I gave up my academic orgullo, my academic pride, and accepted what Francisco was telling me to do. I let him do what he wanted, and it was very successful. The production of the seedlings was very good. By the third year, the seedlings started to drop off their “baby needles” that were long and very tender, and produced needles that were short, thick, and resistant to frost.

After the third year at 3,000 meters, they were ready to be at a very cold site. We transported these seedlings from the Ejido la Mesa nursery in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve to our planting site at the Nevado de Toluca volcano. At 3,800 meters, we had 80% survival! That is an absolute success. We planted under the shade of these shrubs.

There are many things that we combined that are usually no good. It’s difficult to plant seedlings at 3,800 meters, because we’re operating out of a small town, with no good roads, labor is expensive because people have to transport themselves. We had to prepare them for this elevation and induce hardening of the seedlings to resist frost damage. I had read about this, but it was very different to do it in practice. You have to listen to these guys who know a lot about the seedlings, to get it done.

This is brilliant. Local ecological knowledge.

Yes. Some people in academia have arrogance, like “I have a Ph.D., you have elementary school at most, I am the one to be listened to here.” But that’s not true. I may know how to use a statistical program to calculate a p-value for analysis of variants, but the people living on the land know many things that I don’t know. We have to combine our knowledge and together find new ways of adapting forest management to survive climatic change.

What are your goals for long-time resilience? I believe I read that you mentioned a need for 5,000 mature oyamel firs at higher elevations by mid-century?

The basic thing that we have to do is just to follow the experiment for more years, of course. Our paper is about three growing seasons on the ground. We’ve found that the most critical one is the first growing season. We planted at the start of the rainy season of 2021, the rainy season starts in June of July. The critical period is the following warm and dry period, March to May. In this part of Mexico, March to May are the driest and warmest months of the year. If the seedlings survive that March to May of the following year after planting, mostly they are going to make it. The mortality happens the first year, and then it’s mostly stable survival.

So we want to follow this for more years. And, of course, we are ensayando, trying, to demonstrate that establishing an overwintering site here is doable. But we are not exactly establishing the overwintering site yet, because we need many more trees. We’ve planted 30 blocks at our site, each block has eight seedlings, so 240 seedlings. We had some mortality, leaving 200 seedlings. 200 seedlings are not enough for an overwintering site. We need to plant 5,000. But we don’t have the money, the resources, to do that.

We have been funded for ten years by the NGO Monarch Butterfly Fund, from Madison, Wisconsin, run by Karen Oberhouser. They are kind and generous, but this is small funding. It’s not enough to keep me running, and I have to search for other funding where I can. A little here, a little there. We currently can survive with something like $10,000 or $12,000 U.S. dollars per year. Not including our salaries, because my salary is paid by the university and my graduate students have fellowships. So that’s just paying for field labor, gasoline, lodging. The Monarch Butterfly Fund has provided between $4,000 and $8,000 per year, and the difference I obtain from other funds.

This is incredibly important work you’re doing, future-proofing the overwintering site habitat a butterfly species that’s beloved across the North American continent. You’re safeguarding their future on a shoestring budget. I hope that writing this article will gain you more attention.

We are proving that it’s possible to do it, but we cannot do it at a large scale. We need massive planting at Nevado de Toluca. We have to convince these people in the ecology and conservation group that say, “Oh, no, no, no.” I received a critique that said “Above 3,500 or 3,600 meters, there’s no oyamel.” This person told me, “You are planting invasive species! At that elevation Abies religiosa will be invasive!”

Well, the climate is going to be there! These species belong to a climate that is going to be there in the near future due to global warming. It belongs there! That’s where they’ll be able to survive! We come from a historic stable climate, and that is gone. It is over. In Mexico, I have data, unpublished, that mean average temperature in 2023 was 1.6 degrees C warmer than the average temperature during our reference period in 1961-1990. Past the 1.5-degree goal set by the Paris Agreement. The historic climate is gone. It is over. We have to move the forest. We have to move the trees, plant the seedlings at a higher elevation to find a place where it will be adapted.

It’s hard to change what we learned in university. But what we learned in university is something that comes from a stable climate, and a stable climate is over. We have to learn again our ecology. We need a new ecology in universities.

I really profoundly agree with this. I’m so glad that you’re doing this important work.

And I’m glad that the name of your site says “Anthropocene,” because we really are in the Anthropocene. You know the movie about a meteor impacting the Earth, Don’t Look Up? I really like that movie. At the end, the final dinner, the guy that is working for NASA says something like, “At least we tried.” I see myself in that role. I’m trying.

And! If we succeed in establishing a potential overwintering site in the Nevado de Toluca, we are not 100% sure that the monarchs would change their place of overwintering. Because, you know, the monarchs that come to Mexico have never been here. It’s a multigenerational migration, this generation is born in southeast Canada and the northeast United States. They have some inherited system of navigation, from southern Canada to here. We are not completely sure that the monarchs will shift their place of overwintering, but we have hope. Why do we have hope? Because this 2023-24 winter, the winter that just happened, the largest colony of monarchs were not inside the historic sites in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve. The largest colony of monarchs was in Nevado de Toluca!

Not in this lot where we’re planting seedlings at 3,800 meters, which is on the northeast side of the mountain. The largest colony of monarchs was lower down on the southwest side, where there had previously only been very small colonies. This last winter, they arrived to a site at 3,400 meters of elevation. And we’ve found that Nevado de Toluca is one degree Celsius colder than the same elevation at MBBR. [Factors like windchill can influence this kind of regional microclimate]. One degree Celsius is roughly equal to about 200 meters of elevation difference. So 3,400 meters at Nevado de Toluca roughly equals 3,600 meters in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve. Meaning, in my view, that the monarchs are looking for colder places! Why? Because their places of overwintering are too warm today. That indicates to me that the monarchs have the plasticity to shift the places!

I’m saying this not as an expert in monarchs. I work with trees. But that’s my interpretation, that monarchs are searching for colder places, and eventually they will reach the site where we are planting. So that’s why I feel like that. At least I am trying!

This is incredible. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

I think that our responsibility in the university is to try to do different things. The things that we do in a traditional way are not enough. Many things we used to do are not enough when you have over 420 parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere. We have to do a transition in forest management towards adaptation to climatic change. And that requires taking hard decisions, like to move the forest to a higher elevation. Sounds crazy! But look, one species on the slope of a mountain has two limits. In the upper part, the limit is usually low temperatures. In the lower part, the limit is usually drought, the xeric limit. There’s a paper about this by a guy from Hungary, Mátyás, in 2010 in Nature that develops this concept of the xeric limit.

The mortality is going to happen starting in the lower limit, because the trees are already at the limit of where they can be, and that climate is gone. The trees cannot move. In Lord of the Rings, the trees are walking, but here they cannot walk. We must help them to move.

“The trees cannot move.

In Lord of the Rings, the trees are walking, but here they cannot walk.

We must help them to move.”

-Dr. Cuauhtémoc Sáenz-Romero

We have to develop a new sense of the responsibilities of the university. We have to have open minds. We have to forget things that we learned. The books we studied when I was a student were written under a stable climate, and that stable climate is gone. We’re exceeding 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming. We have to do something different. My message is, we have to open minds, listen to local people, and put together scientific research with local wisdom to find together new solutions. That’s my message.

That is brilliant. Thank you so, so much.

Thank you very much.

One of the rare non-Hispanic common first names in Mexico today, the original Cuauhtémoc was the eleventh tlatoani of Tenochtitlan and the last Aztec Emperor, who led the last desperate defense of the city against invading conquistadors and is today considered a national hero of Mexico.

The professor is absolutely inspirational. Great interview, Sam!

The concept of the nurse plant reminds me of the successes of Miyawaki forests. This interview also reminds me of "Finding the Mother Tree" and the connections between all plants in a forest. Too bad the forestry industry hasn't caught on. Incredible point you make about the paltry funding for such a beloved species.