The Restoration of the Presumpscot River: a Case Study

One small river in Maine comes back to life

The Weekly Anthropocene interviewed Michael Shaughnessy of Friends of the Presumpscot in June 2019. Now, we’re republishing this interview for Substack, with some new updates!

All around the developed world, the rivers are coming back. From the Mersey in Liverpool to the Don in Toronto, from the Meuse in the Netherlands to the Kissimmee in Florida, from the Cheonggyecheon in Seoul to the Manzanares in Madrid, we see the same story of hard-won victories. Waterways pummeled by decades of pollution, exploitation, and neglect are growing into healthy ecosystems once again. with fish and birds returning to cleaner waters in droves thanks to the dedicated actions of local teams of ecologists and activists. Other major cities around the world are working to follow these examples, with the Seine in Paris and the Bronx in New York City at the center of ongoing restoration projects. In this article, The Weekly Anthropocene explores a case study of this global river restoration trend: the ecological rebirth of the Presumpscot, this writer’s home watershed.

The Presumpscot River in the state of Maine, United States of America, is relatively small as rivers go, stretching a mere 25.8 miles from Sebago Lake to Casco Bay. However, it has immense ecological value and a rich cultural and economic history. Centuries ago, the Presumpscot was home to immense fish runs of salmon, herring, shad, and more, most of which were wiped out by the mills, dams, and pollution of the Industrial Revolution. Now, some of the fish runs are coming back, thanks to the tireless work of scientists, activists, and local citizens.

Michael Shaughnessy is a University of Southern Maine art professor, specializing in sculpting, as well as a founder and the current president of the Friends of the Presumpscot, an organization vital to the river’s recent history. In this interview, we explore the history, ecology, and future of the Penobscot River through an interview with Mr. Shaughnessy, one of its most dedicated advocates. For more information on the Presumpscot, check out www.presumpscotriver.org.

Could you tell me about the ecological history of the Presumpscot? What did the river look like hundreds of years ago, before it was industrialized? What fish runs were there, and what was the river’s importance to the Wabanaki people?

The Ancient Ecology of the Presumpscot.

Well, the name Presumpscot in Wabanaki means River of Many Falls. Before industrialization, it was known amongst the Wabanaki of the Northeast as having an abundance of waterfalls. It was an enormous salmon, herring, shad, and all anadromous fish fishery that came up here to spawn. They came from Casco Bay up through the river to Sebago Lake. It was an incredibly productive river. Let me stress the falls part of it. The river drops 250 feet over 25 miles, so it drops 10 feet per mile. There were 14 named sets of falls, named by settlers, and if you think about it, that’s an enormous amount of significant waterfalls. It’d be like looking at Presumpscot Falls or Saccarappa Falls and multiplying it by 14, which is phenomenal. The fish runs weren’t just “there’s fish there,” it was “reach in and grab a fish” levels of fish. The rivers were churning, it was phenomenal.

The Industrialization of the River.

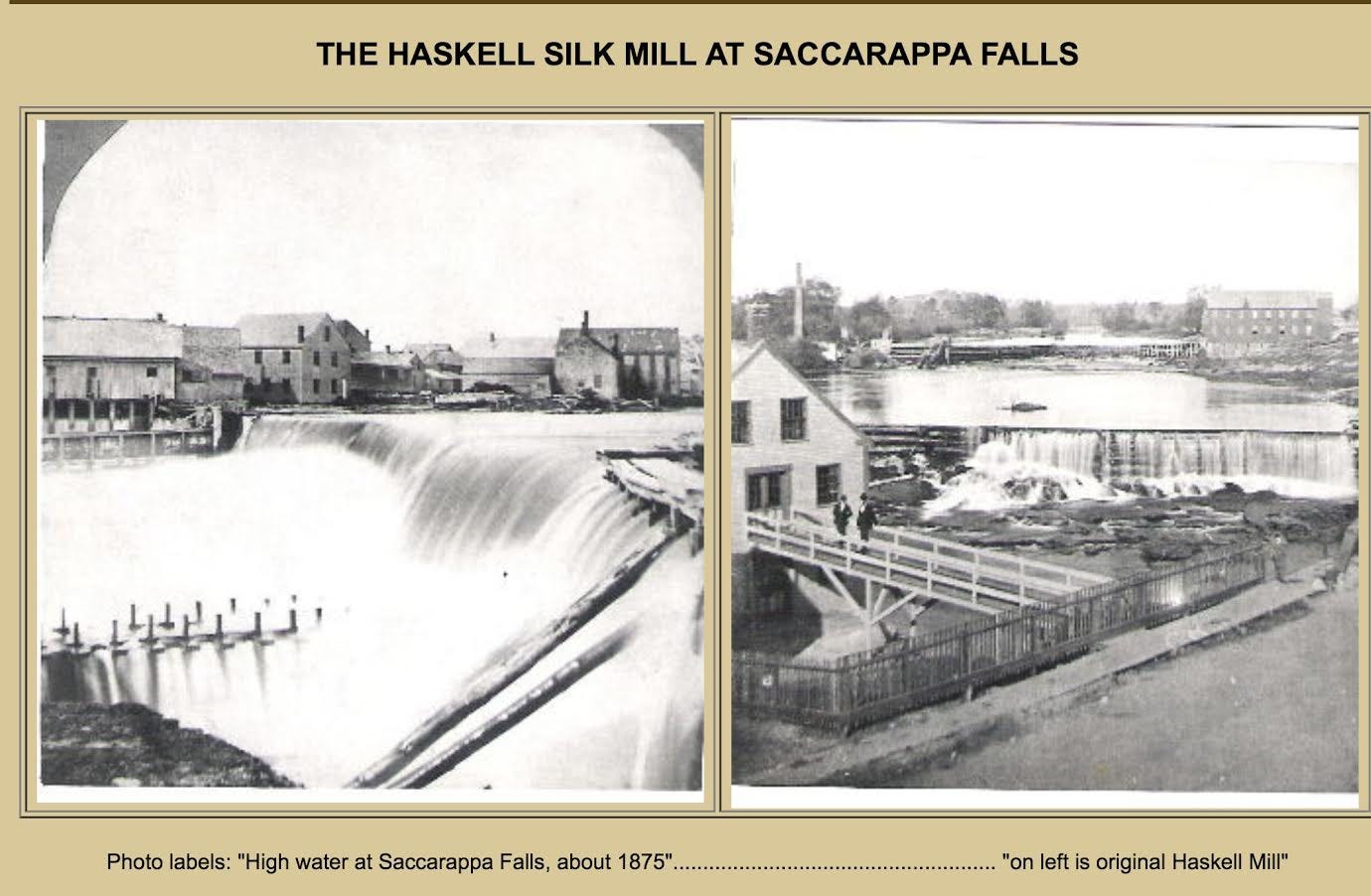

Then with industrialization, the first dams were logging dams, and they were meant to raise the levels of the river so the log rafts could float down. They logged the region, then pulled them out onto Sebago Lake, and during the spring runs, float them down. But they had to raise the level of the river so the rafts wouldn’t drag on the bottom. So those were the first dams. Then there were the smaller mill dams, your classic waterwheels. They were all over the place, and an industry might have a few, or up to a dozen. Not enormous businesses, it might be a place that makes chairs, or a grist mill, or whatever. (Pictured: the Haskell Silk Mill, circa 1875). One of the largest was the Gambo Powder Mills, owned by the Oriental Powder Company, which produced an enormous amount of gunpowder. I think it was about a third of all the gunpowder used by the Union Army in the Civil War that was produced on this river. A lot of people died doing it, too, since it would blow up frequently. Produced a lot of gunpowder for the Crimean War as well. They put in the Cumberland-Oxford Canal, as a means of shipping-this was before they had the railroads. It was in the early 1800s, and then it was replaced by the railroads, then your big industrials started to come along. You had large industrial areas in South Windham and in Westbrook, those were the major industrial centers. The Dana Ward mill used to be on the island in the middle of Saccarappa Falls. S.D. Warren began as a small mill-that was begun by Colonel Westbrook1 himself. Those became the industrial landscape as we have seen it now.

The Abenaki and Chief Polin.

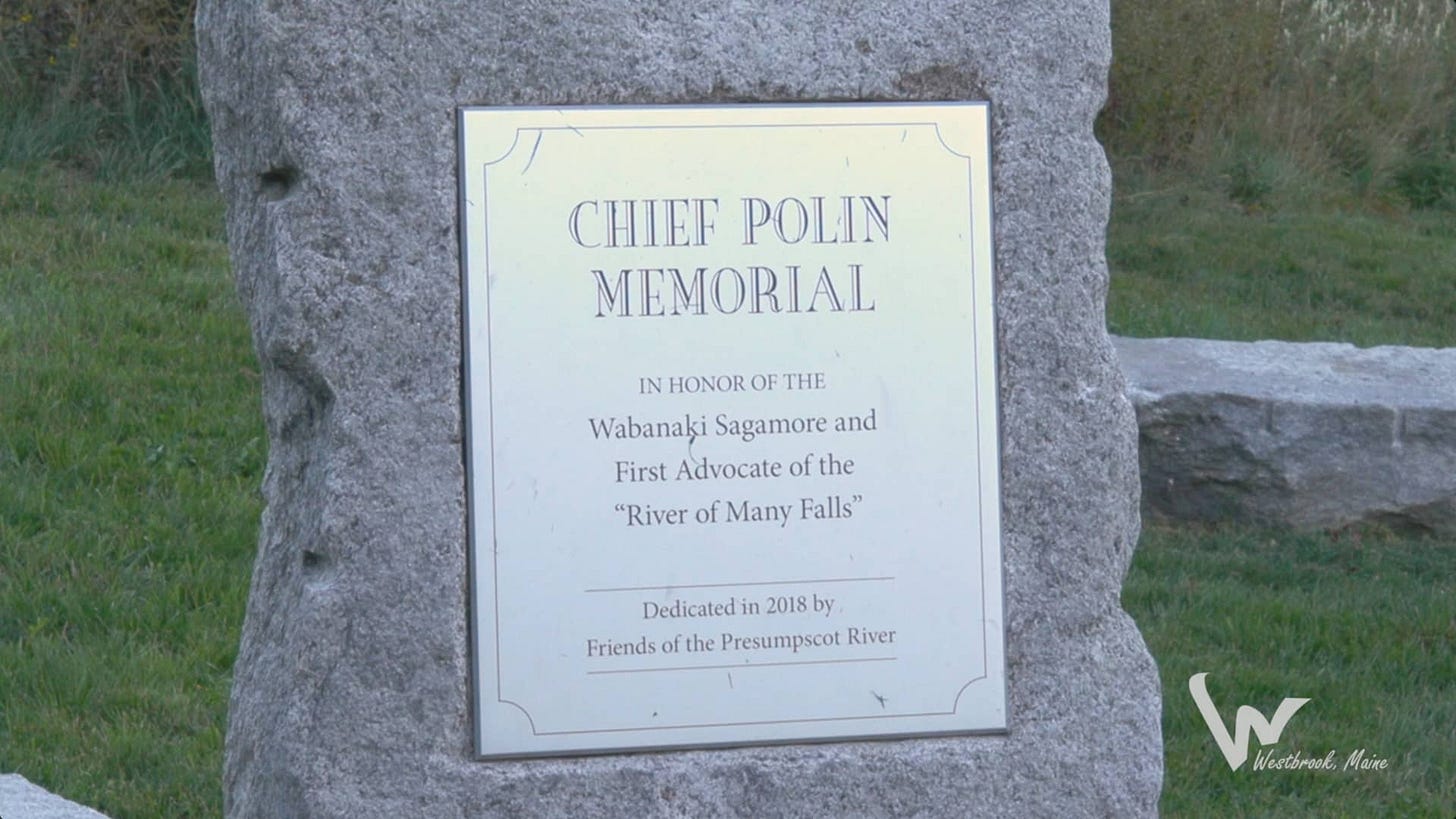

To add another dimension to it, the First Peoples here, the Wabanaki, were a confederacy of tribes-the Passamaquoddy, Micmac, Maliseet, Penobscot, and Abenaki (pictured, a 1700s watercolor of an Abenaki couple). The Abenaki lived on the Presumpscot, and were driven off by the first mill owners. There was a time when these mills were being built, they were damming up the river, and the Abenaki who lived there attempted to, in the person of Chief Polin, to request that these mills put in fish passage. This was in the 1730s. Chief Polin had walked down to Boston twice to request this. We have to appreciate that there was a civilization here that was way before any settlers. A group of people lived for fourteen thousand years here, and they had families, and villages, and crops, they lived seasonally, thriving off the fish runs. They would dry them out and eat them through the year. They were a group of human beings that we basically eradicated by cutting off their food supply. The mills were not simply a means of production and creating power, they were a means of genocide as well.

“They were a group of human beings that we basically eradicated by cutting off their food supply. The mills were not simply a means of production and creating power, they were a means of genocide as well.”

When Polin requested that the mills have fish passage-he didn’t even request that the settlers leave, he just asked for fish passage when the fish were running. The technology was there, he was really saying “We can live here at the same time, this is a resource that we all can use. You can have your mills and dams, just let the fish come up.” The governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony then was a close friend of Colonel Westbrook, so it fell on deaf ears. With the death of Chief Polin in 1756, the Abenaki were pushed into either hiding or away from here altogether. That culture of the Presumpscot ceased to exist at that time.

A Power Source and a Sewer: The River’s Nadir.

So to skip ahead, the industries came in, and it looked like Polin had been the last advocate for the river. The fish stocks would were there only because they would trickle up through the existing canal, which worked as an unintentional fish passage, and because the wood dams blew out a lot so the fish could get up. But the populations were nothing like they used to be. Then in 1898, there was a major flood, which undercut buildings, and that’s when they decided “The heck with the wood dams.” So concrete dams were built throughout the river, and that was the end of the fish runs. That caused the extinction of a species particular to the Presumpscot, the Presumpscot jumper, which was a landlocked salmon that had evolved into a shorter, more muscular salmon because of the falls. The fisheries were dead, and the river was buried in these long, thin, impoundments.

“The river basically served two functions: to make power and as a sewer…It was an ecological disaster.”

When Polin was gone, there ceased to be any advocates. The river had a park down in Portland, and there was a little recreational use, but the river basically served two functions: to make power and as a sewer. There were times when SD Warren was complaining that the wood mills upriver were turning the river so brown they couldn’t make paper out it-and then below SD Warren, it was so acidic you couldn’t build a house near it. It was an ecological disaster.

Only with the advent of the Clean Water Act did that function as a sewer start to cease. Before that, when they built a swimming pool too close to the river, kids were getting typhoid. The dams were built because of this big 100-year flood, then it became a sewer, then the Clean Water Act helped clean up the river immensely, but still it had that reputation.

The Fight to Restore the Presumpscot

We came about, the Friends, to pick up the mantle of Chief Polin, to fight for the restoration of the fisheries of the Presumpscot. One of the things that helped with that is that 100 years after the great flood, in 1998, there was another flood, and it sent a log down through the lower river into the turbines of Smelt Hill Dam, which in effect destroyed it, because the turbines were 100 years old and couldn’t be fixed. The irony of it is that it was the dams that undercut the soil along the banks, so if you see a tree leaning into the river, it’s because of the dams raising the water level.

What happened is that next flood a tree fell down and went through the turbines. So in effect the dam killed itself. It was deemed not economical to replace it, and then the fish came back up, and they made it up to the next dam, at Westbrook. Soon after that Sappi, who owned the SD Warren mill, needed to relicense its hydro dams, and decided to apply for five of them at the same time. (Pictured above: an elevation profile of the Penobscot River, showing the dams ).

In that process, the public can intervene, can “speak now or forever hold their peace.” So the Friends, along with a few other organizations, intervened in that process. We requested that three dams be taken down, and that the other two have fish passage. FERC decided that wasn’t going to be the case, but we did get that all the dams had to have fish passage, for herring. We weren’t completely satisfied, but it was better that nothing.

In the process of all of this, they contested us all the way to the Supreme Court. There was a provision in the Clean Water Act that said that the state has the capacity to license any discharge into the river-that’s Section 401 of the CWA. Sappi basically said, “No, it’s not a discharge, it’s the same water above the dam as it is below the dam.” Our position was “No, it is.”

It goes through a series-the DEP, the BEP, circuit courts, superior courts, and it just moved up the channels, and it went to the US Supreme Court in 2006. They kept getting beaten and appealing to the higher court. That was decided in 2006, and it affected every hydro dam in the United States. (In the case S. D. Warren Co. v. Maine Board of Environmental Protection, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that discharges from a dam counted as discharges under Section 401 of the Clean Water Act, and thus could be regulated by the states).

With that, the FERC licensing and the state licensing was settled. This little river…things have ripple effects. The FERC licenses on these five dams held, but there was a provision that said that before these go into effect, you have to get fish passage. So that was another fight…they’re like battles, if the war is about the entire river. We had to get fish passage there, so that was a very long litigious time.

We used a state statute that had never been used before, which said if you could prove that there was a need for fish passage, that the fish were trying to get up, then the state could order fish passage. Maine DEP Commissioner Roland Martin ended up ordering that they needed to put in fish passage (in 2010). Sappi built this magnificent fish passage at Cumberland Falls, and then there were a certain number of years before they needed to put in fish passage at Saccarappa.

But the number of fish at Saccarappa determine when or if the next dams upriver get fish passage. So it was imperative to get good fish passage at Saccarappa. Now, in a few months, we’re going to see construction that will take away the dams and build fish passage at Saccarappa (pictured, the Saccarappa Dam in downtown Westbrook). That’ll revert it to, more or less, when it was 350 years ago. Beneath our river is a river-this long impoundment will become a river again. That’ll restore about half of the run of the river. When they took out that dam on the lower river, the waterfalls reemerged.

The Presumpscot’s Glorious Future.

So we could get it all back.

If they were to take everything off, this would be chock-full of waterfalls and rapids, and it would be full of waterfowl and just be a magnificent river. (Pictured: a section of the Presumpscot near Eel Weir that retains some of the character of the ancient river). In Missouri, where I’m from, a river like these would definitely be a state park or even a national scenic waterway. But Maine has so many other rivers, it gets overlooked.

One of the side effects of the dams and the pollution is that beneath those dams, few of the industries built along the river. It was brown, and it stunk, and you couldn’t swim in it. When my wife and I bought our first house, it was right on the river, and the realtor didn’t advertise that at all. Even then, in the 1990s, the river was not seen as a positive aspect of a property. So this bad reputation has actually kept it undeveloped in long stretches.

The Return of the River Herring

I was at Highland Lake [in spring 2019], volunteering with the Presumpscot Regional Land Trust by counting alewives (Alosa pseudoharengus, pictured below) going over the fish passage there. Highland Lake drains into Mill Brook which drains into the Presumpscot. Could you tell me more about the impact of your work on the broader watershed, and on alewives particularly? I don’t know if you know my former academic advisor, Dr. Karen Wilson, but she’s done a lot of work on this issue.

When the Smelt Hill Dam came off, they really started to come back. They came up Mill Brook to Highland Lake, and they have gotten in the last few years back up into the forty-fifty thousands, which are strong numbers. Last year, according to Sappi, there were 52,000 herring that made it up over Cumberland Mills. So there’s at least 100,000 herring, which may include both alewives and blueback herring (Alosa aestivalis). (Both of these “river herring” species, alewives and blue herring, along with other Presumpscot natives like Atlantic salmon are dubbed “anadromous” as they spawn in fresh water but grow to adulthood in the sea). Anadromous fish are mostly in the Northern Hemisphere. The only place that there’s any wild Atlantic salmon in America is in Maine. Of 30,000 known species of fish, only about 200 of them can go between freshwater and saltwater. There’s so few of them, and it’s such a delicate balance. Now, some things are going to be harder to come back than others. We have to get a good herring population before we can get an Atlantic salmon population.

It’s hard, and it’s work that takes generations to do. We’ve been an organization for 27 years. But the optimistic side of me says that people like you-and thank goodness people like you exist-wouldn’t have existed 25 years ago. There’s becoming more of a consciousness of issues like this. The will of the people, that values the river and its resources, will supplant the industrial-economic value. We will value the river simply for its existence. We can look out and go “There are all these fish and waterfalls that used to be here, and we can bring them back if we care about them.” The entire river produces around 11 megawatts of electricity-and that’s at full capacity, which it never is. Just for perspective, the gas fired power plant on Saco Street produces 450 megawatts. The dam at Saccarappa had like 1.2 megawatts…these are small, small dams, for the amount of damage that they do. For context, since this interview took place, a 175 megawatt grid-scale battery storage project was announced in the area.

If you destroy the fishery, you’re damaging our offshore fishery. We’re known as a fishing state. But those fish and lobster are only there because they eat the little fish coming out of these rivers. Well, I say little fish-we’re also seeing shortnose and Atlantic sturgeon coming back, which is phenomenal. They jump out of the water and slap, it’s a mating thing. They show we can bring it all back.

“The will of the people, that values the river and its resources, will supplant the industrial-economic value. We will value the river simply for its existence. We can look out and go ‘There are all these fish and waterfalls that used to be here, and we can bring them back if we care about them.’”

Thank you so much for sharing your experience and for all the work you’ve done for the Presumpscot. Thank you so much for joining this interview. It’s been a pleasure talking with you.

Thank you.

Postscript: 2023

Since this interview took place in 2019, the Saccarappa Dam has been fully removed. As of June 2023, the Presumpscot River alewife run was at 50,000 to 100,000 fish. Also in June 2023, the Maine Legislature passed a bill strengthening legal protections against wastewater discharges in the Presumpscot. Towns along the river continue to purchase more riverfront land for conservation. Wildlife continue to return.

Colonel Westbrook, an early Maine colonist, mill builder, and militia officer in the 1740s. The namesake of Westbrook, Maine, where this interview took place.

So grateful for the work of the Friends of the Presumpscot.

That's a fantastic story. So good to read of positive environmental progress. But all that went before is heartbreaking.

It's interesting to me right now because I'm looking at New Zealand waterways and what it will take to restore some of them. I interviewed someone about lake restoration today and it's such a long game, you need people who have that intergenerational vision.