Review: Inheritors of the Earth by Chris D. Thomas

Immigrant species are generally neutral to beneficial; the whole concept of "invasive species" is mostly fallacious (at least when they're vertebrates on continents)

Since I was a little kid, I’ve been fascinated by environmental questions; this newsletter is about the relationship between humanity and its biosphere, after all. One of the sub-fields of environmental science that never made quite as much sense to me was “invasive species biology,” the idea that humans’ rapid introduction of many species to new continents is always -or at least mostly- a bad thing, with detrimental effects on the local ecosystem. Despite growing counterevidence, this paradigm is still pretty commonly accepted in the wildlife conservation field at the moment; a new United Nations report was just published excoriating invasive species, and the United States government continues to fund large anti-invasive species programs.

At first, the only real counterweight I had was my own anecdotal experience. On my way to class as a teenager in Maine, I’d routinely pass Japanese honeysuckle bushes in flower, with a wide range of native bumblebee species and other pollinators supping at the feast. Later, as a volunteer research assistant in the Vatovavy region of Madagascar, I learned that the critically endangered greater bamboo lemur had grown to rely on the invasive soapbush (Clidemia hirta) as a source of “weaning food” berries to help their young transition from milk to bamboo. I also noted that “invasive” eucalyptus trees from Australia were prized by the local people as a source of throat-soothing medicines, and seemed to be doing no harm to the local ecosystem as one of many tree species in the forest.

The book that really crystallized my thinking on this was Inheritors of the Earth: How Nature is Thriving in the Age of Extinction, by Professor Chris D. Thomas, Director of the Leverhulme Centre for Anthropocene Biodiversity at the University of York. It came out in 2017 to a smattering of positive, surprised-seeming reviews, but in my view didn’t make near as much of an impact as it should have. This book really deserved to be a Silent Spring-level shift in the zeitgeist!

Reading Inheritors of the Earth gave me a firm evidentiary background for a controversial new paradigm that has become one of this newsletter's long-standing talking points: the inadequacy and outdatedness of the idea that species in a given area are either "native" or "invasive." The idea of “invasive species,” or “native species” for that matter, is a human-created artificial dichotomy which makes no sense when describing the ecological reality of Earth in the Anthropocene. Today, "native" species around the globe are moving poleward or up mountains in the face of rising temperatures. And some "invasive" species are in fact critically endangered in their homeland and should be protected where they've managed to find new habitat Even if not actively good, the vast majority of "invasive" species are, contary to popular belief, harmless, with the case against them often based less on science than on reflexive nativism, a weirdly ideological “blood and soil ecology,” and an unrealistic idea of attaining ecological "purity."

I’ve been thinking and writing about this for years, and this review has arisen because I’ve finally had the time to put it all together.

A Quick Caveat

To get the two big exceptions out of the way first, this (mostly) applies to invasive species that are on continents or large islands (not small islands) and not a parasitical or disease organisms.

Dr. Thomas isn’t arguing that the amphibian-killing global chytrid fungus plague or the forest-devastating chestnut blight are good, or that rats and cats and brown tree snakes devastating small islands’ bird populations are good. He discusses both cases, and acknowledges the losses. But he does argue, backed by an increasingly wide array of evidence, that “invasive” plants and animals on continents generally have positive effects on the broader ecosystem. One of his case studies in particular really drives this point home for me.

The Great Evergreen Switcheroo

Yet Inheritors of the Earth goes further than simply saying that most invasive species are “not bad.” Dr. Thomas provides many striking examples of instances where a species becoming “invasive” elsewhere is a massive positive good. The case of the Monterey pine, the blue gum tree, and the monarch butterfly from Chapter 11 of Inheritors of the Earth is probably the one that I’ve found most impactful. I call it “The Great Evergreen Switcheroo,” and it’s shaped my thinking for years. It really deserves to be told in full.

Consider the Monterey pine, Pinus radiata, an endangered species native to the Pacific coast of North America and known for historically providing a winter shelter for monarch butterflies. At first glance, it seems like a tragic tale of Anthropocene vulnerability, of the kind that readers of this newsletter have probably heard all too often. Even without considering the physical impact of urbanization, the Monterey pine evolved for California’s historical coastal landscape in a way that’s hard to square with the demands of modern humans: they need a temperature range that’s not too hot and not too cold, just the right amount of moisture, and also the occasional smallish forest fire to release their seeds from their resin-sealed cones without getting too hot and turning them to ash. But unfortunately, climate change is now making California much drier. The wildfires that do arise tend to be too intense, or (understandably) put out when they near human houses…which tend to be built on the coast where the Monterey pine likes to grow. Local authorities have taken to manually extracting the seeds from the cones and then planting them, one of the key factors keeping the species alive.

As if that wasn’t enough, they’re also threatened by an invasive species: Eucalyptus globulus, the blue gum tree from Australia, which out-competes them in the warming, drying, modern climate. As a result of all this, the Monterey pine has become one of America’s rarest trees.

However, in the words of the great Gilbert & Sullivan, “things are seldom what they seem.” The Pacific coast isn’t the only place where you can find Monterey pines nowadays; they were introduced to New Zealand in the 1850s. Dr. Thomas’ prose best conveys what happened to them there:

“It seemed as though the tree had been yearning for antipodean weather all along. New Zealand’s moderate climate, bathed by the waters of the south Pacific, was ideal for the sensitive tree. Growing about seven times faster than back home in California, radiata, as it is now known, has become the mainstay of New Zealand forestry, covering some 18,000 square kilometres of plantations….

And it didn’t stop there. Radiata now generates around 95% of Chile’s timber production and forms the largest part of Australia’s plantation wood. It is grown in Argentina, Kenya, Uruguay, and South Africa, where the climate is so ideal that the tree has gone wild…A species perched on a few coastal cliffs in California has become a global colonist – an endangered species converted into an heir to the world.”

-Inheritors of the Earth

(Furthermore, although not covered in the book, a 2019 study by Wyse, Brown, and Hulme found that Monterey pines in New Zealand seem to be evolving, or just adapting, to open their cones without fire, passively soaking in sunlight and then opening to spread their seeds during the hot winds of summer. The study framed this as increasing its “invasion risk,” but from the tree’s perspective it’s just what’s needed for a long, happy future in its new home).

I think it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the Monterey pine is doing pretty great! And yet it is still considered to be an endangered species! Check out the Pinus radiata article on Wikipedia; IUCN ranks it as “Endangered,” and the parallel NatureServe classification system ranks it as “Critically Imperiled.” Everyone knows that vast cultivated and newly wild “feral” forests of Monterey pine exist, but they don’t “count” towards official rankings of the species’ overall well-being, as it goes against the longstanding paradigms of invasive species biology. Now, that categorization is not necessarily a bad thing, and certainly not a malicious thing – it’s good to be trying to keep the tree alive in its homeland too, and I totally get how someone could work hard to keep the species marked “endangered” to draw attention there! – but it creates a misleading portrait of the world. This is the kind of thing that can make the global biodiversity situation look a lot worse than it actually is.

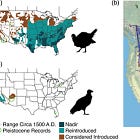

But species don’t exist in isolation: what about the ecosystems formed by and with the Monterey pine in California, and the other species that evolved to interact with them? What about the monarch butterflies?

That’s where this story gets really interesting. Remember those invasive blue gum trees back in California that were making life harder for the Monterey pines? Turns out that monarch butterflies actually prefer the broader, more sheltering leaves of the “invasive” Eucalyptus globulus to the needles of the Monterey pine, their historic habitat, and the blue gum tree provides near-ideal conditions for monarch butterflies to settle down for the winter. So much so, in fact, that local conservationists have realized that attempting to replace eucalyptuses with Monterey pines would demonstrably harm monarch butterfly populations, and that planting more “invasive” blue gums can be one of the most effective methods of monarch butterfly conservation! A recent scientific paper has the blunt title, “Nearly all California monarch overwintering groves require non-native trees.”

The sheer poetic symmetry of it is breathtaking. Remember, Australia is one of the countries where Monterey pines have become super common, and that’s where the blue gum trees are from. So a corner of Australia and a corner of North America have essentially swapped their local evergreen trees! Both the blue gum tree and the Monterey pine have become world travelers, probably at a much lower risk of extinction than they would be in a human-less world where they’d be confined to one continent.

And remember, according to traditional concepts of “invasive” and “native” species, this is all bad. This gets categorized as “more invasive species” plus “imperiled native species” and gets docketed as further evidence of the horrible impact humans are having on the planet.

But it’s so clearly not bad. The Great Evergreen Switcheroo is, in this writer’s opinion, pretty awesome! The Monterey pines get to grow all over the world, the blue gum tree gets to grow all over the world, the monarch butterflies get nicer, roomier winter quarters. Even the California population of the Monterey pine isn’t doomed yet; a lot of people care deeply about them, and have already chosen to become an essential new component of their reproductive process. All three species here win, plus the humans who got a nice lumber tree in New Zealand and better monarch butterfly habitat in California!

Invasive Species: Often Not Actually Bad

Once you start looking at the “invasive species” concept in a different way, you start to realize how absolutely crazy it can get, how virulent and violent the turn towards attacking newly arrived species can become. Any justification at all is acceptable to condemn a new species: the media will jump on it with apocalyptic language, portraying them as “scary,” “invading,” a “rampage” or a “horde.” I suspect but cannot prove that indulging the knee-jerk nativism common to invasive species rhetoric makes us slightly worse as people. There are frankly disturbing parallels to the way the extreme political right talks about human immigrants: absurd double standards, fearmongering, and seizing on any negative news while ignoring massive positive contributions.

There are so many incredible opportunities being ignored here! So many success stories where species from elsewhere have contributed massively to their new ecosystems, sometimes even “trading places” for a positive-sum outcome like the Great Evergreen Switcheroo. In the way we currently discuss species moving around in the Anthropocene, everything is viewed through a negative prism, when the reality is often neutral or positive, even in some of the most-hyped “dangerous invasives” case studies. Here’s my recent article investigating some of the new research around invasive species previously listed as among the hundred “World’s Worst.”

The Matter of Britain

Dr. Thomas’ arguments are most powerful when applied to his homeland of Britain. In one striking scene, he begins digging a hole in his Yorkshire backyard to examine the ecological history recorded by the soil strata. For the last three centuries, his land was hay meadow, immortalized by sandy soils. Before that, plow-churned soils from historic grain fields. Before that, deciduous forest, from five to ten thousand years ago. Before that, a post-glacial mammoth steppe, which left a completely different soil layer. And a layer of thick clay below even that immortalizes Lake Humber, the glacial lake that covered much of Yorkshire fifteen thousand years ago.

“The set of species present on my own bit of land has been almost completely replaced at least four times in the last fifteen thousand years, and at least forty times in the last million years…

Not only have the inhabitants of my small spot on Earth always been interlopers, but this is also true of every spot on Earth.”

-Inheritors of the Earth

This legacy, particularly notable in the relatively recently glaciated British Isles, creates some interesting questions that nibble away at the very idea of “invasive” or “native” species. The glacial lake ecosystems in the Britain of 13,000 BCE were home to species like Arctic char, Arctic fox, and snowy owls, all of which still exist but are not considered “native” to Britain today; the suite of “traditionally native” British wildlife like oaks and red squirrels arrived thousands of years later. And just a few thousand years after that, brown hares and sweet chestnut trees were likely introduced by the Roman Empire sometime around 1 to 100 CE, but they’re still considered “native.” The sycamore tree was probably introduced by the Tudors in the 1500s; debate is ongoing whether they’re “native” or not. Rhododendrons were first planted in Britain in 1763 and Himalayan balsam in 1839, and they are both targeted as “invasive.” As Dr. Thomas points out, this makes absolutely no sense. The whole concept of “invasive” and “native” are fallacious human attempts to immortalize a snapshot in time as the One True Natural way that an ecosystem should be, and that’s just not how nature works.

“It is completely illogical…to hate a fellow human, or another animal or plant, simply because they or their ancestors were somewhere else at a particular time.”

-Inheritors of the Earth

“Genetic Pollution” Isn’t A Real Thing; Hybridization Forming New Species is Normal and Good

One of the most awe-inspiring parts of Inheritors of the Earth is the chapter simply entitled “Hybrid.” New species often form in nature thanks to self-sustaining hybridizations between existing species (like the Clymene dolphin, born of spinner dolphins and striped dolphins). As has become common knowledge in recent years, ancestral Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, and Denisovan hominids hybridized all the time. Humans moving more species around is accelerating this ancient species-diversification process in surprising and even heartwarming ways. Here are some examples from the book:

Two different species of flowering ragworts (genus Senecio) from different elevations in Italy interbred in a botanic garden in Oxford in the 1800s, creating the unique Oxford ragwort which subsequently spread across Britain thanks to the growing railway system. When the Oxford ragwort reached York, it hybridized with the common native groundsel to create York ragwort (Senecio eboracensis), now cherished a rare local species in its own right. And in Wales, a random mutation in a sterile Oxford/local ragwort hybrid created a unique self-sustaining Welsh ragwort, Senecio cambrensis! Three new species.

“As far as we know, no British plant species has become globally extinct over the same period that the Senecio species were diversifying…This means that the contribution of human actions within the geographic confines of Britain over the last three centuries has been to increase the number of plant species on the planet.”

-Inheritors of the Earth

And that’s not even all the new species from plants hybridizing in the UK! The famed “nation of gardeners” has also seen the birth of a new monkeyflower species in Scotland (Erythranthe peregrina) and a new cordgrass species in southern England, Spartina anglica. S. anglica actually became so successful that it made it onto that IUCN list of the “World’s Worst” invasive species!

It’s a similar story in North America. (And probably around the world to a greater or lesser extent, but Europe and North America are where we have the most reports from botanists). Two new species of salsify flowers were identified in the Pacific Northwest, born from hybridization between two introduced European species. The increasingly unique California star-thistle population speciated “from the other direction,” so to speak: it was introduced from Europe, but they’ve been separated so long that they’ve gone off on their own evolutionary path and now find it hard to interbreed.

“More information is still needed, but the hybrid generation of new plant species in Europe and North America already seems to be as fast as the process of extinction, and possibly even faster.”

-Inheritors of the Earth

Moving from plants to animals, most surviving American bison herds contain some domestic cattle genes thanks to matings in the 1800s. Although sometimes attacked as “beefalo,” they look like and play the ecological role of bison. Plus, it was recently discovered that the cherished European bison species was the result of a similar hybridization about 120,000 years ago, between aurochs and steppe bison.

In Scotland, the native red deer has extensively hybridized with the “immigrant” sika deer from East Asia, creating a never-before-seen population of “Scottish red sika deer”, not quite considered to be their own species yet but seemingly heading that direction. Bafflingly, the BBC reported this as a “threat” to red deer, which are a highly successful species that themselves are regarded as invasive in Australia, Argentina, and New Zealand.

The Italian sparrow (Passer italiae) was born from hybridization between the Spanish sparrow (Passer hispaniolensis) and the originally-Asian world-travelling common house sparrow (Passer domesticus). Italian sparrows are now thriving across the Italian Peninsula as a visually and genetically distinct self-perpetuating new species.

Pennsylvania recently became home to many fragrant honeysuckle bushes. Themselves hybrids of three Asian species, they’ve also enabled hybridization in local “native” fruit flies. The North American blueberry fly and the North American snowberry fly normally don’t interbreed because they stick to their eponymous bushes and don’t meet each other, but they both were willing to check out the new honeysuckle berries, and a brand new “North American honeysuckle fly” has been the result!

“The current rate at which new species are forming on Earth is starting to look as though it is the highest ever, or at least the highest since animals and plants first colonized the land.”

-Inheritors of the Earth

But research on these multitudinous new Anthropocene hybridizations, this rich and bountiful fountain of new life, is marginal compared to fearmongering against hybrids cloaked in the mantle of scientific authority. In the name of conservation, humans regularly kill hybrids in an attempt to “preserve” endangered species, who one suspects would not sign up for having their literal own children killed to preserve the abstract concept of genetic purity. The United States government guns down hybrids between spotted owls and barred owls by the thousands, the UK government attempts to exterminate hybrids between ruddy ducks and Eurasian white-headed ducks, and New Zealand kills hybrids between pied stilts and black stilts.

This is absurd, arrogant, and above all, simply wrong. The idea of “genetic pollution,” stripped of its authoritative sounding moniker, boils down to an insane attempt to charge wild plants and animals with “miscegenation.” When you think about what is actually being criticized here, the whole concept is straight-up morally wrong. If you’re hearing “genetic pollution” in a conservation context, it means that someone is upset that a free-living creature had sex with another free-living creature that in some human’s opinion they should not have had! It’s like some weird fossilized version of early-20th century racism that somehow managed to dig in to conservation biology.

“The idea that humans can or should police hybridization is ludicrous.”

-Inheritors of the Earth

Now, I’m certainly not trying to invoke accusations of prejudice to “cancel” all invasive species biologists, or say that anyone who’s ever worked on any conservation project that uses the term “genetic pollution” is a bad person, or anything silly like that. I just think it’s really clearly time for science to move on from the concept of “genetic pollution” the same way we moved away from “geocentrism” and “spontaneous generation” and “phlogiston” and “luminiferous aether”, and for the same reason; it’s not describing a real empirical fact, but a phantasm in the human mind.

“Surprising as it may seem, it is entirely possible that the long-term consequence of the evolution of Homo sapiens will be to increase the number of species on the Earth’s land surface.”

-Inheritors of the Earth

The Glorious Future of Results-Focused Conservation & Intentional Novel Ecosystem Creation

One could write a version of this article that would sound like a stereotypical lone voice railing against inflexible dogma. And there is a little bit of that; the traditional stereotypes about “invasive” species still define most people’s ideas of introduced vs. native species, and it’s important to break through those preconceptions.

However, the good news is that the overwhelming majority of people in the wildlife biology and conservation fields are smart, open-minded, compassionate people who care a lot about animals and are pretty receptive to interesting new data. Without making a big deal out of it, more and more research and conservation projects are acting on what I call the “immigrant species” concept, that introduced species often bring positive benefits. I wrote a whole article about it recently!

Ready for some excitement? Let’s talk about Section 10(j)!

And there’s reason to think that this sensible results-focused approach is gaining institutional ground. One of the most exciting recent moves towards a new, positive, open-minded “immigrant species” dynamic in the United States sounds really boring at first, but it’s actually quite fascinating.

The Fish and Wildlife Service recently released new regulations based on Section 10 (j) of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), which will for the first allow “experimental populations” of endangered species to be established outside their historic range. This sounds like the epitome of bureaucratic tedium, but it actually represents a paradigm shift in wildlife conservation thinking that will help make possible a multitude of new projects to help America’s animals and plants survive the Anthropocene.

Section 10 (j) is the ESA provision that allows the reintroduction of endangered species into areas where they used to live but have disappeared, like the classic case of wolves returning to Yellowstone1. Allowing projects like this to take place in areas where the endangered species at issue hasn’t previously lived is a critical legal tool to allow conservationists to proactively adapt to the changing landscapes of the Anthropocene. Climate change is forcing many creatures to move north, inland, or otherwise into new realms, and the US government is now able to help them do that. For example, a translocation project is already being considered for the Key deer, a diminutive white-tailed deer relative native to the Florida Keys whose historic range is at risk of becoming uninhabitable (for the deer) due to saltwater intrusion from sea level rise. It will also help species like the Guam rail and Guam kingfisher, birds whose eponymous island is no longer safe due to the invasive brown tree snake. Under the new rules, they could get a chance to start fresh on a new, snake-free Pacific island.

Moving into pure speculation, this writer hopes to see their home state of Maine, with its plentiful wild spaces and relatively cooler temperatures, become a new “climate refugia” habitat for endangered species from southern New England, the mid-Atlantic region, and even the South. Starting with more spatially proximate states, a quick review of FWS records reveals that there are 10 endangered species found in Massachusetts but not in Maine: the dwarf wedgemussel, American chaffseed, Northeastern bulrush, sandplain gerardia, seabeach amaranth, American burying beetle, Northeastern beach tiger beetle, Puritan tiger beetle, bog turtle, and Plymouth redbelly turtle. It would now be legally possible for any or all to be introduced into Maine in a (purely hypothetical) future climate adaptation program, to help these creatures benefit from temperatures closer to the ones they evolved in, plus more wilderness areas2. This new regulatory tweak opens up fascinating possibilities for truly proactive conservation efforts across Anthropocene America, and will hopefully resonate for decades to come.

In conclusion: conservation biology must adopt the Hemsworth Principle

It’s time for conservation biology to adopt what I’m calling the Hemsworth Principle: a species is not a place, it’s a people. In the fast-changing biosphere of the 21st century, we must judge species on their merits, not their origins. To cheekily paraphrase, I dream of a world where wildlife may be judged not by its biogeographic history but by the content of its character.

That doesn’t mean “anything goes”: sometimes introduced or native species need to be checked to prevent negative outcomes to the ecosystem or human health. If local disease-carrying mosquitoes are causing a major ecosystem or human health threat, they should be countered or even eradicated whether they’re introduced or native, just as much as rats destroying the ecology of a Pacific atoll. But we should choose to intervene based on the goals and values we have for our ecosystems and communities, not based on enforcing fictional “genetic purity,” an arbitary cutoff of “nativeness,” or fighting an increasingly imaginary concept of “invasiveness.”

Wake up and smell the hybridized immigrant wildflowers; there’s an amazing new wild world outside to explore and cherish! Marvellous new species, species communities, and ecosystems are emerging across Anthropocene Earth. Pet-descended parrots fly overhead in cities around the world, insects and plants from different continents find new mutualistic dances of living together, and species that never encountered each other before humans brought them together are producing unique new lineages of life!

According to the traditional conservation paradigm - the best knowledge we had for a long time - all of these would be negatives, as they aren't the "natural" state of the ecosystem. But in the Anthropocene, with massive, existential shifts such as human-caused climate change upending ecosystems around the globe, it's time to support and celebrate examples of successful "immigrant" species where we can find them. Aldo Leopold famously said that the first rule of intelligent tinkering was to keep all the parts. We need to use all the tools at our disposal to conserve species and help protect and rebuild functioning ecosystems, wherever they are, and with whatever biological "parts" become available.

Mere nerdiness trivia, but I still feel compelled to share that I always mentally hear “Section 10(j)” as sounding like/rhyming with the chorus of “Forgot About Dre.” Dun dun dun dah dah…Section-ten-jay! It’s a really cool little piece of law, okay?!

To be clear, I know of no plans whatsoever to do this, and it might or might not be a good idea for the specific circumstances of these particular species: it’s just an example of the kind of proactive, Anthropocene-ready conservation relocation that could be possible now!

Hi Sam, thanks for a thoughtful piece. Here's a reaction: "native" versus "invasive" is not the appropriate dichotomy. Most non-native plants are not invasive. According to the brilliant work of Dr. Doug Tallamy (who would have erudite things to say about this piece) about 10% of non-native plants in eastern US suburban settings are invasive, meaning they displace native plants. And this is key: native plants and insects have co-evolved; native insects need native plants as host plants, which are essential to their reproductive cycle. For example, Monarchs required Milkweed species to feed their caterpillars. The non-native black swallow-wort plant has been introduced to the US east. It is close enough to Milkweed (same Family) to fool Monarchs to lay their eggs on it, but the caterpillars cannot eat it and die. So the host plant concept is crucial to the analysis of native plant and insect ecology.

Sam, with all due respect I'd recommend that you continue your studies in this area, because this topic is too important to leave your audience with an incomplete impression. If 'invasive' is too pejorative a term, I've heard 'aggressive alien' species used to convey the idea.

Regardless, I'd recommend the work of Dr. Douglas Tallamy to help you understand further. He's an entomologist, which is key to his major insight that native plants are in fact vital to local food webs, because they are what the local insect populations have evolved to eat (& thereby serve as the energy transfer link from plants to animals) - think caterpillars, and think all the birds who rely on caterpillars as their major protein source for breeding and raising their young. It is a fact that many invasive plants are simply inedible by local insect populations, because they have not evolved the capability to digest them. When this happens at scale, the energy transfer from plants to animals is reduced. Less energy coming through the food web, less diversity of life.

When you start to get a sense of the interconnected picture of the food web, you realize it's not enough to see some plants doing well, or serving a slice of the pollinator population (as with your honeysuckle example).

Lastly, I'd invite you to take a walk through an oak / hickory forest, for example, here in southwest Michigan, in which honeysuckle and autumn olive have become established in the understory. It may look like they are supporting pollinators and birds - in fact autumn olive was distributed for planting 40 years ago because bird lovers back then thought (incorrectly as it turns out) those shrubs would support migrating bird populations. What is happening is that these invasives (yes, in this context they deserve the label) are so successful in the understory (because guess what, the insects and deer leave them alone so they outcompete natives!) that there is a scarcity of younger oaks and hickories coming up to succeed the overstory trees.

If you're interested, here's a link to a talk by Dr. Tallamy from earlier this year: https://youtu.be/9_FlSBwUr_s?si=2y1b7UJmEy5z10q3

Thanks for your work, Sam, and keep it going!