Morocco is a country on the way up

With rich phosphorus and solar resources plus burgeoning industrialization and a strong geopolitical position, the Kingdom of the West is well positioned for the Anthropocene

In the 1000s and 1100s, the lands that are now Morocco were one of the richest and most technologically advanced parts of human civilization. In the 1170s, the Almohad capital of Fes (“the Athens of Africa”) may have briefly been the most populous city in the world1.

In October 2023, I visited Morocco for the first time. It was a relatively short tourist stay, primarily visiting the cities of Rabat and Fes. Taken in conjunction with a range of interesting environmental and economic stories about Morocco recently, the experience inspired the writing of this article.

I posit that by the 2100s—perhaps much sooner—Morocco may again be in the first rank of developed nations. Many long-term trends on Anthropocene Earth are providing a strong tailwind to its economic prospects.

Article continues below paywall.

Morocco is already a fairly prosperous middle-income country by global standards, with consistent growth in recent years (minus the global COVID dip). It’s also increasingly industrialized with a robust car-making industry. Its location close to Europe and with ports on both the Atlantic and the Mediterranean positions it well for global trade.

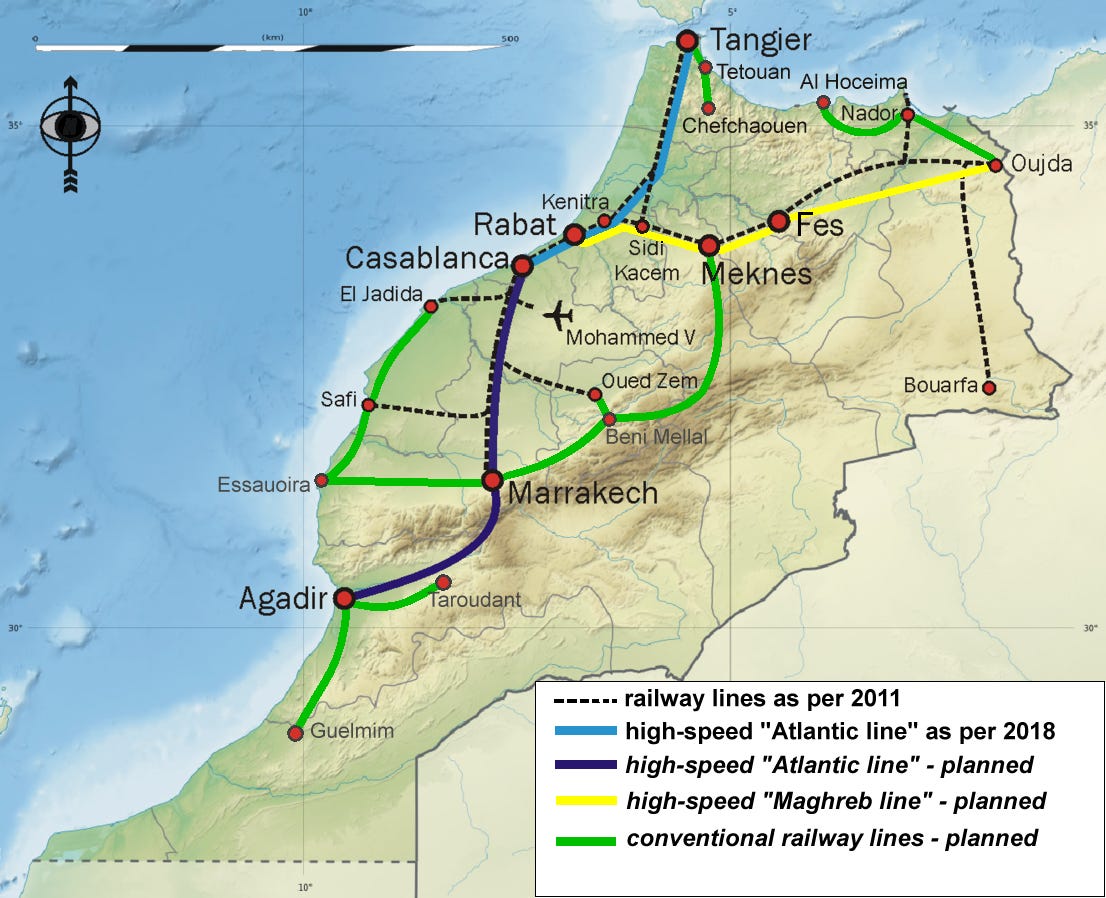

Morocco also has a really impressive rail network, with plans to expand it substantially in the coming years. In 2018, the Sharifian Empire inaugurated the first-ever high-speed rail train on the continent of Africa, dubbed Al-Boraq2, which currently links Casablanca on the Atlantic to Tangier on the Mediterranean, passing through the capital of Rabat along the way. An extension southward to Marrakech and Agadir is in the works, plus a second high-speed line going east from Rabat to the Algerian border. This is a good indicator of state capacity for long-term planning and productive infrastructure development.

And perhaps most enticingly for the future, the Kingdom of the West is rich in two resources that are increasingly vital on Anthropocene Earth: sunlight and phosphorus.

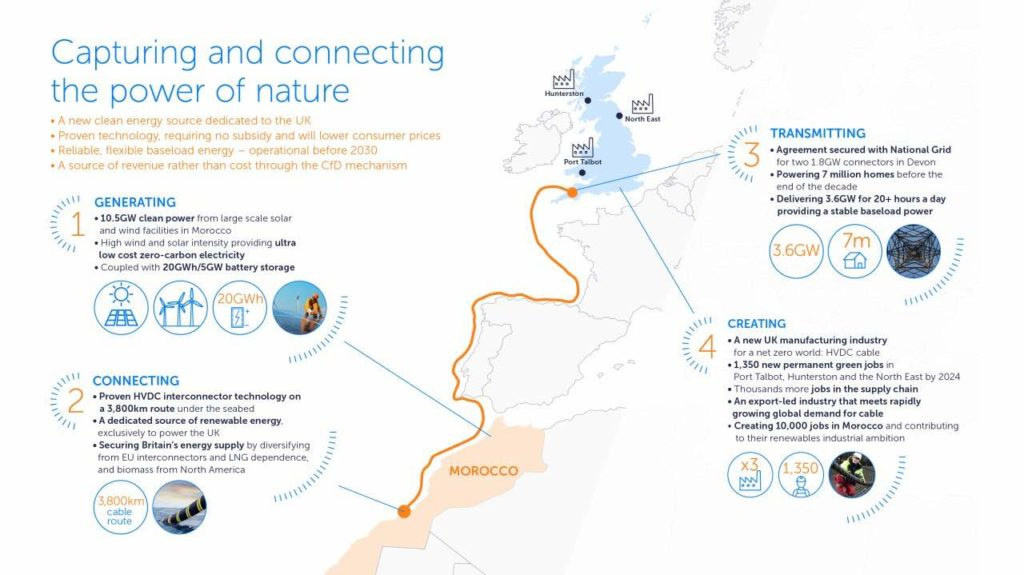

Morocco is investing heavily in building massive solar farms in the desert, with a view to selling vast amounts of power to Europe with extra-long high-voltage transmission lines. The nation has everything it needs to become a key player in the emerging World Grid.

One early example of this is the in-development Xlinks Morocco–UK Power Project, which seeks to build 10.5 gigawatts3 (10,500 MW!) of solar generating capacity in Moroccan deserts, then send the power to Great Britain via the world’s longest undersea power cable. Whether Xlinks happens as planned or not (or an interim outcome like being scaled down or delayed), the economic logic of such a project is so manifest (big deserts with lots of sun year-round here, power markets hungry for clean electrons there, cheap solar and battery technology to make it feasible), that something like it is going to be built sooner or later. Morocco can and should scale this up: there’s space for many more Xlinks level solar buildouts! And if Europe’s electricity needs are eventually sated, Morocco could become a global hub for enterprises that benefit from ultra-cheap electricity, from desalination plants to data centers4 to industrial chemical manufacturing. Maybe in the 2060s, if you need a whole bunch of cheap electricity to run some experimental new mega-AI or an array of giant lasers for a Breakthrough Starshot-type project, you go to the sparkling solar fields of Morocco.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Weekly Anthropocene to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.