The Weekly Anthropocene Interviews: Greg Watson, Systems Organizer

A World Grid is being built, the long journey of American offshore wind, farmers' markets in Boston, and more!

Greg Watson is Director of Policy and Systems Design at the Schumacher Center for a New Economics. He previously established the Massachusetts Office of Science and Technology, served as first Executive Director of the Massachusetts Renewable Energy Trust, served as Massachusetts Commissioner of Agriculture from 1990-1993 and 2012-2014, and founded the U.S. Offshore Wind Collaborative.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Mr. Watson’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

I’ve been following your fascinating series of LinkedIn posts with the tagline “The world grid is self-organizing invisibly right before our eyes.” Could you give a general explanation of what this is, why it's important, and what's changed recently?

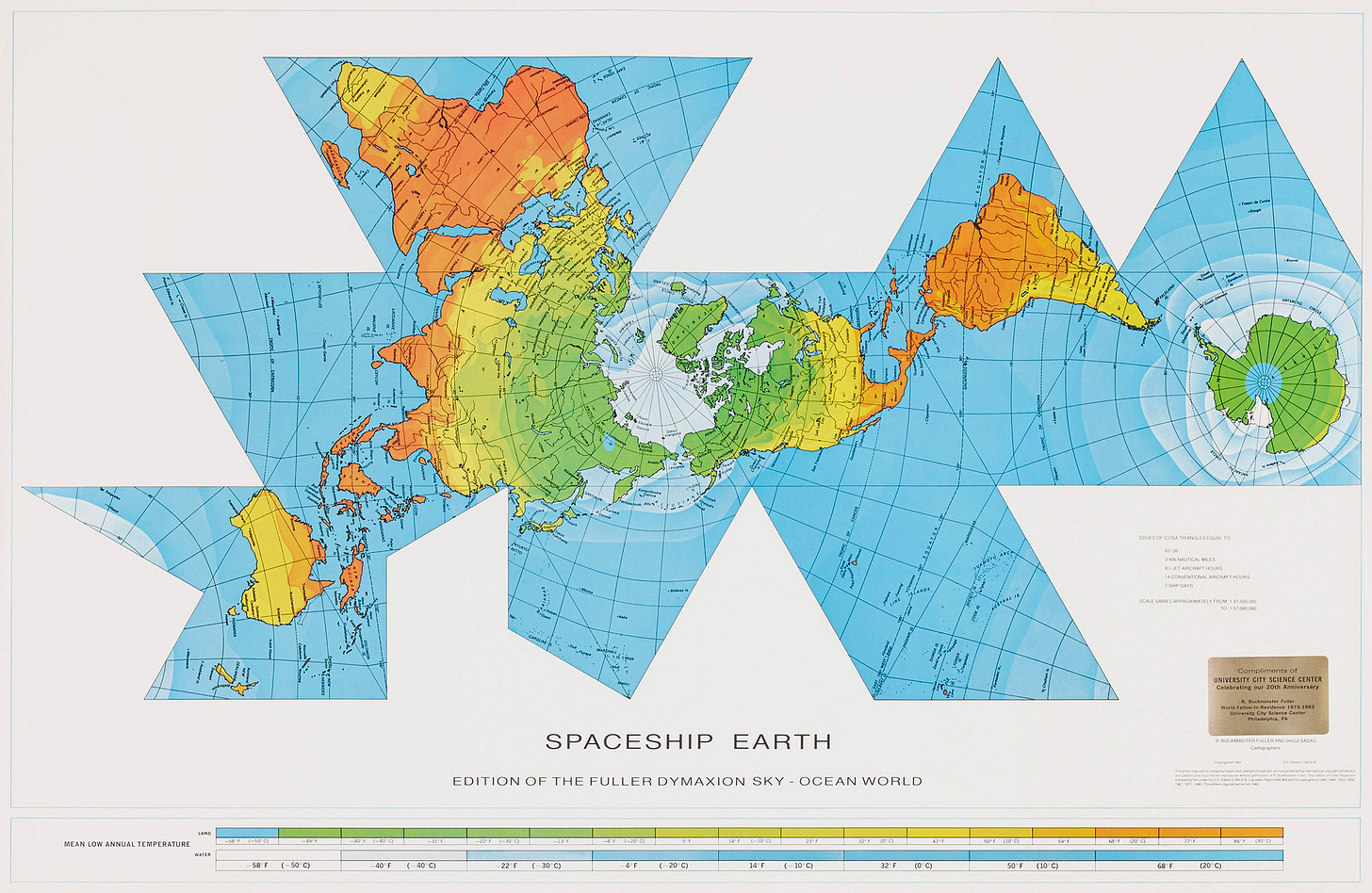

I’ll start with Bucky Fuller. When he created and patented his Dymaxion Map, he meant to provide a new perspective on the world. He wanted to do that because he was concerned about the projections that the Mercator Projection creates-Greenland is much bigger than it should be, the continents’ size and geographic relationship to each other gets distorted. He created the Dymaxion Map, a 20-sided icosahedron, that when you unfold it shows the continents in their proper geographic relationship to each other with minimal distortion. Fuller understood that accurate representations of whole systems reveal what he called “trimtabs”—places where desired changes can be leveraged most effectively (via technology, policy and/or organizing) with the least expenditure of energy and resources. He saw, wow, the Earth is actually a one-island, one-ocean planet. You see the continents sort of strung out, and he looked at that and said, we could connect the entire world with one grid.

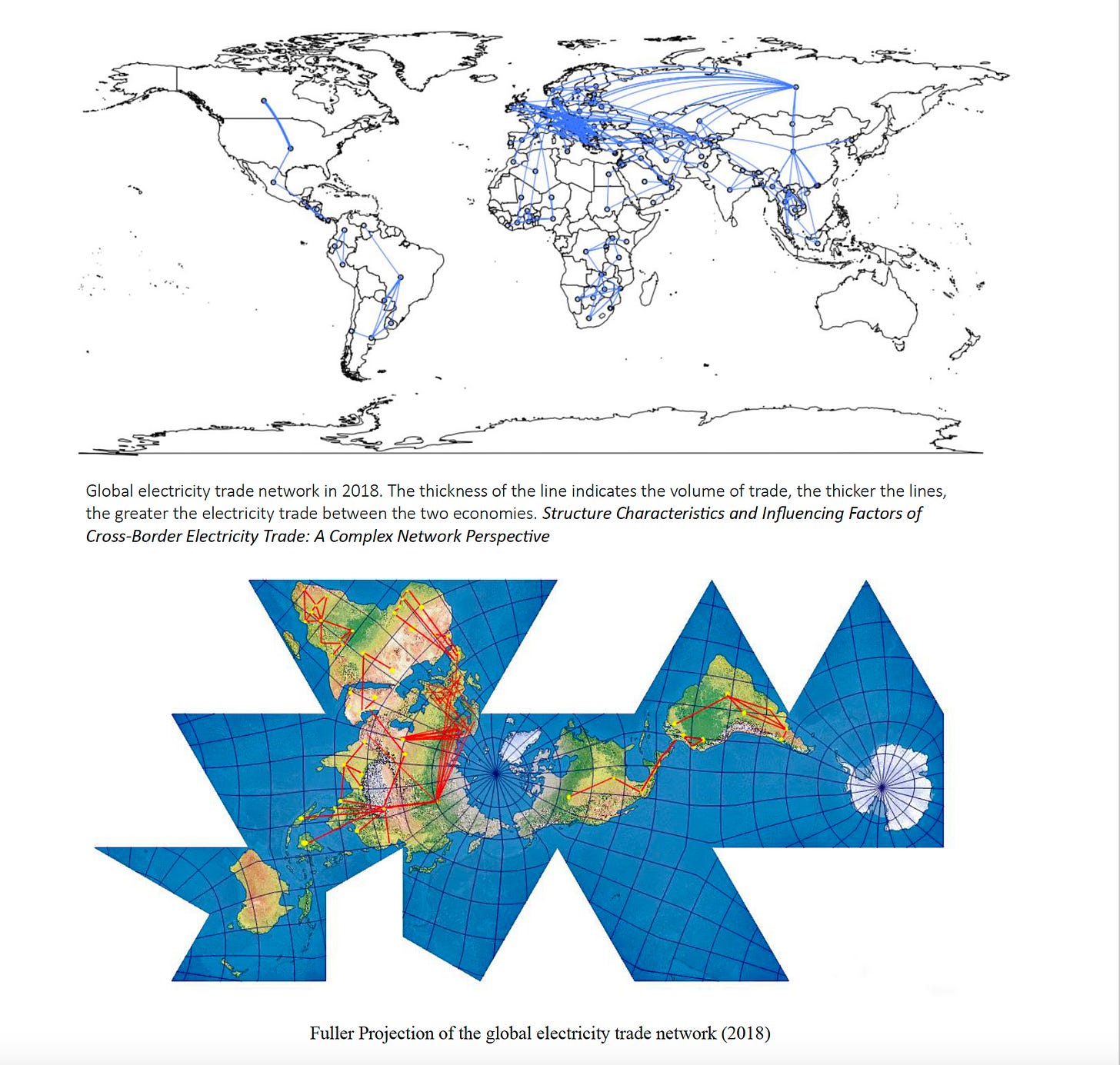

That led him to this notion of creating a World Grid. And the reason why that’s important, segueing to the present, is that I don’t think there’s any way we can achieve a world of 100% renewable energy unless we create the world grid. There’s too much redundancy with every country trying to go it alone. If we cooperated, and created a world grid, we could basically reduce the amount of resources, the metals and minerals, that would be required in order for us to achieve that goal. A globally connected electric grid would yield synergetically greater environmental and economic benefits than the sum of its nation-state parts operating in isolation could. That’s our best shot at doing this. People countered that by saying, it’s impossible, you’ll never achieve that level of cooperation. So I just started this survey on my own, to figure out what’s going on. I realized there’s this phenomenon called cross-border electricity trade. We don’t hear that much about it in the US, but…

Okay, let backtrack one step further. The reason why the idea of connecting the grids is also important, beyond just the resources that would be conserved, is that that’s the best way for us to deal with intermittency and variability of solar and wind. The sun is always shining and the wind is always flowing somewhere, and the question is, what do you do about the differences?

At nighttime, when things quiet down, businesses close in one part of the country or one part of the world, the demand for electricity goes down. But if you're relying on renewable energy, let's say wind energy at night, that's when the wind energy actually increases. So you're generating electricity with wind, but you don't have a demand for it because it's nighttime. You can store it, but storing it requires materials, metals and minerals for batteries. Or if we could transmit over a long enough distance so that we could actually take that wind energy that's being generated at night and supply it to a part of the country or the world where there's a demand for it because of the difference in time. You can actually sell that electricity in real time, and eliminate the need for storage. There’s a supply and demand complementarity that could be met over time and distance.

The real technology challenge was not a wind turbine or a solar panel, it was the transmission cable. Could you develop transmission capability that was technically and economically feasible to transmit over those distances? And now we can! So this is the big picture.

In Texas and other parts of just the U.S., there are regions where there's wind being generated, can't be used at the time that it's being generated, but could be used in another part of the country if we could transmit it and if our grid system was interconnected, even if you just start interconnecting regionally, So, can we economically and legally come up with the systems that allow us to trade electricity across borders? If we can do that, you’ll find the ability to meet the Sustainable Development Goals and 100% renewable energy can actually happen.

But that’s the theory. How can you possibly overcome the political challenges of getting countries to cooperate? Then I started to discover that it is actually happening. There are countries where spontaneous cooperation was happening, because these countries realized there was mutual benefit in interconnecting their grids. In some cases actually integrating their grids, not just trading electricity across borders—mostly in Europe. Europe’s grid is largely interconnected for the most part.

And they just added Ukraine to the interconnected European grid.

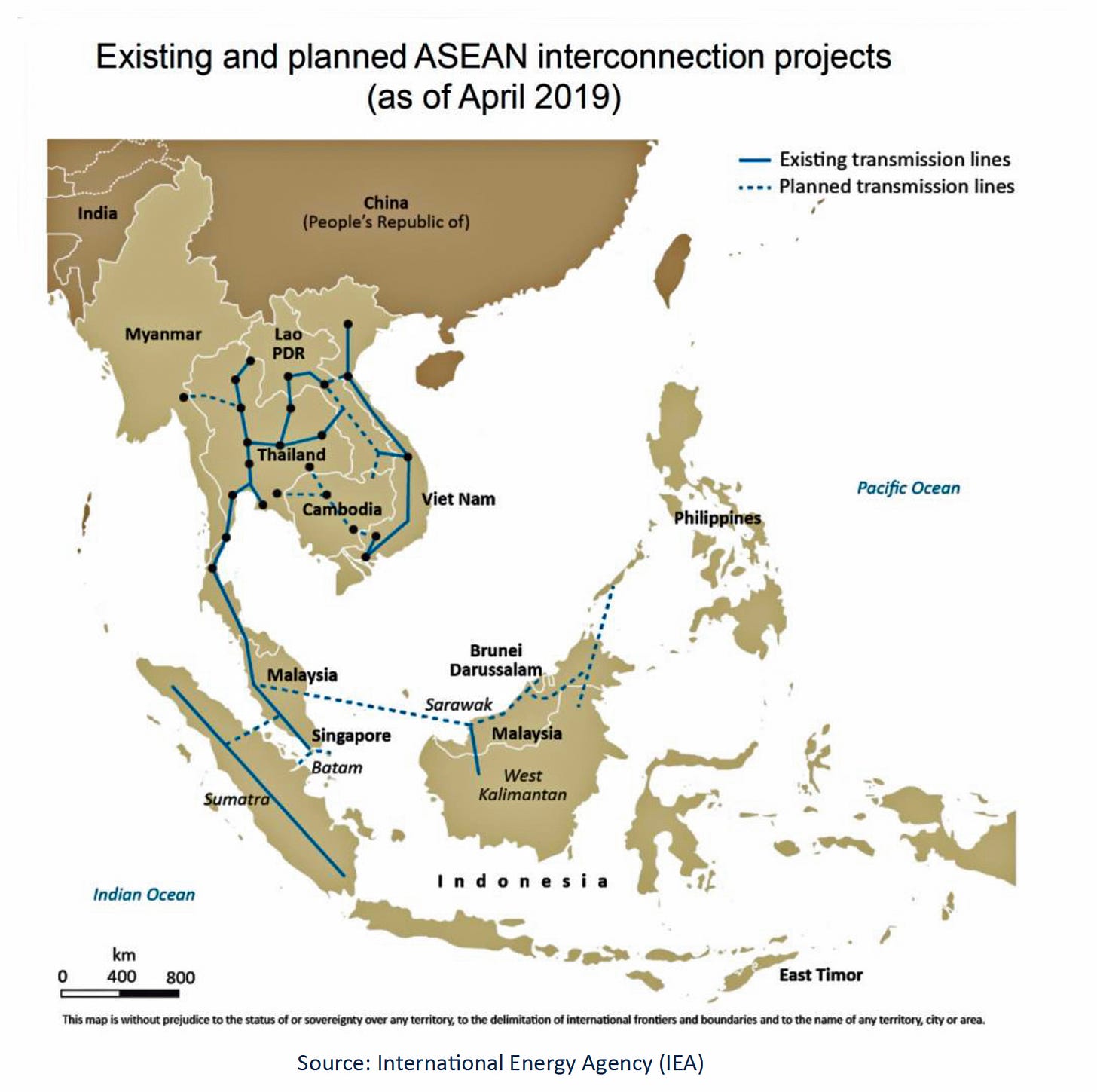

That’s right. So it’s there in Europe, and now South Asia, Southeast Asia, and some parts of Central Asia are saying, “This makes sense.” I’m now tracking it and chronicling it. I’ve actually started something called an Atlas of Geographies of Cooperation. Really just doing two things, identifying where this is happening and then mapping it, showing where they are on a map. Our literacy, our global systems literacy is very low. I picked up a history book on the history of Eurasia in the library, and there wasn’t a single map. I think that hinders our ability to see what’s possible.

“The World Grid is being built.”

-Greg Watson

So that is the byline. The World Grid is being built. Not even consciously, the countries are thinking more regionally, what can we do to make ourselves self-sufficient in energy. They can see that with the energy transition, the world is going to be electrified. This is happening. This is almost like a silent revolution/evolution in our energy system, and there are absolutely some great things about it. One of the things that’s happening as you’re finding is that centers of economic and political power are shifting as a result. Power is accruing to those parts of the world that are now situated to perform the role of electricity hubs—you gotta come through me. There’s a shift in economics, in economic and political power, as a result of this energy transition. There’s a lot going on.

What I’m trying to do, and what Fuller tried to do with his maps, was make the invisible visible, so that people understand what’s happening. Much of Southeast Asia—entire regions are already involved in building the transmission lines that connect. Those are just a few, and I may send you the draft of the Atlas that I’m putting together. It’s pretty exciting. It is important for people to see them, and not just hear the names, because if they can’t visualize where they fit geographically it won’t make a whole lot of sense. We’re also trying to turn it into a World Game Workshop, where people can play the role of regions or governments, look at their resources, and try to come up with more efficient interconnections. So we want people to do this and use it as sort of a way to play the World Game, as Bucky had envisioned it.

You've been involved in the story of offshore wind in the United States for a really long time. In 2005, you coordinated the drafting of “A Framework for Offshore Wind Energy Development in the United States” and the following year you founded the U.S. Offshore Wind Collaborative. You were on Obama’s Department of Energy transition team from the Bush to Obama administration.

Now, offshore wind is finally taking off under the Biden Administration—we’ve got steel in the water at Vineyard Wind off Nantucket and South Fork Wind off Long Island. There’s a lot more projects in the pipeline, and even though some are in flux for financial reasons, we’re clearly finally entering an age of real offshore wind progress. Can you talk about what that feels like to see that arrive?

It’s satisfying. There’s no question. Back in 2001, in Massachusetts, we had just restructured our electric utility industry and opened it up to competition. One of the things consumers can choose is how it’s generated. Before, you were assigned. Now, you could choose your supplier because they’re wind, or solar. This was industrial policy. There’s always this tension, who decides how industry is going to evolve, is it the private sector or government. The private sector feels governments should have minimal say, but we felt it was important to provide incentives to create a level playing field for renewables to compete with fossil fuels.

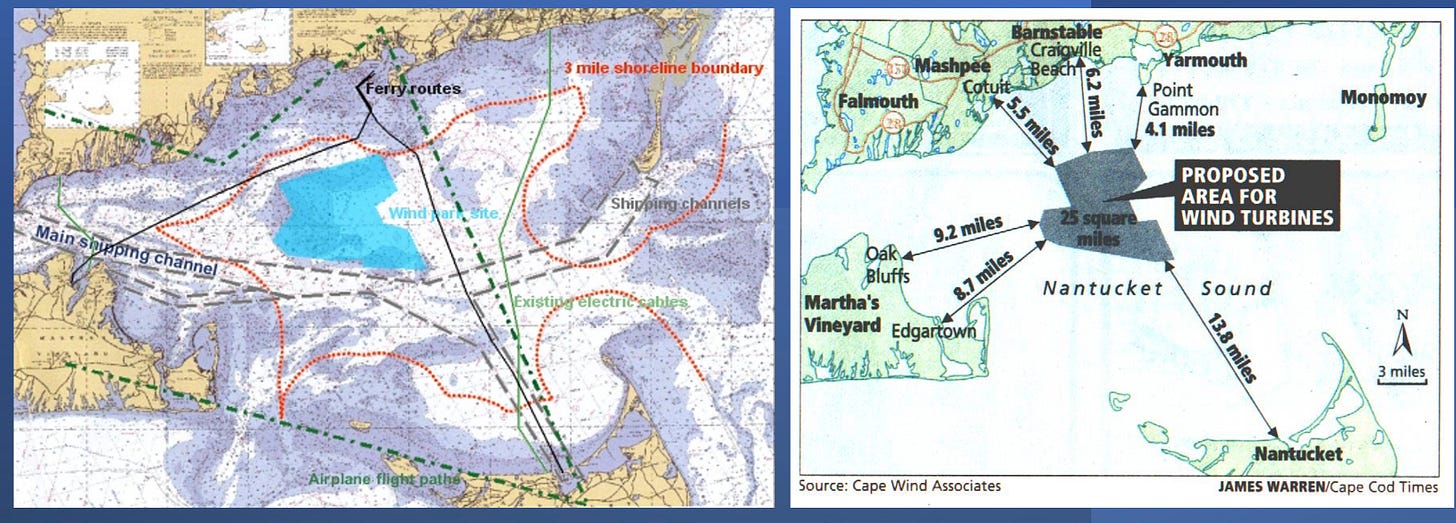

So we were trying to jumpstart the renewable energy industry in Massachusetts. In 2001, there was a developer, Jim Gordon, who had produced all the cleanest power plants were operating in New England— they were combined-cycle natural gas, which were the cleanest power plants at that time. He looked to see what are the possibilities of utility-scale renewable energy in New England. He said, it’s not onshore wind, because you’re too densely populated, siting will be an issue. He went down the list and said, offshore wind. He came and met with us administering this fund, and he said, what do I have to do? And we didn't have an answer. There was nothing in place in the United States to entertain a proposal to build an offshore wind farm. There was no way to permit an offshore wind farm! His project, Cape Wind, became the guinea pig. He put himself out there. And if it weren't for him, we probably would not be seeing the projects we're seeing happening right now in the United States because that’s where we came up with that framework for offshore wind energy.

It’s interesting, that framework document: this was a joint effort between the Massachusetts Technology Collaborative, the US Department of Energy, and GE. There were individuals within each of those three entities that did not want us doing offshore wind. [Then-Massachusetts Senator] Ted Kennedy did not want the offshore wind farm Jim Gordon proposed in Nantucket Sound, where Ted Kennedy sailed. There was hypocrisy going on. I mean, I'm just being very honest. People said they wanted offshore wind, but what Jim Gordon discovered was that even though he said you couldn't build onshore wind because of the siting issues, dense population, turns out there was equal if not more vehement opposition to building them offshore off the coast of Massachusetts.

And it turned out at that time there were strict limits as to where you could put an offshore wind farm with the given technology back in 2001. It had to be shallow water, had to be nearshore. Couldn’t put it where there were other activities. They did overlays, and there was just one little triangle left. Nantucket Sound was the only place in 2001 where you could have built that farm. He wasn’t crazy, he was a prisoner of geography, that was the only place you could put it.

And there was vehement opposition, and the rest of the congressional delegation in Massachusetts, who today are big proponents of renewable energy, they would not challenge Ted Kennedy. So when we asked them, what do you think about the offshore wind project? They would say, what does the senior senator think about it? There was politics.

When we published that framework for offshore wind energy development, the three entities represented in that document were represented by three outliers within each one of the agencies. Offshore wind was sort of a pariah [in Massachusetts], we couldn’t talk about it much but we couldn’t ignore it either. Same in the US Department of Energy, because in 2001 [under Bush] federal policy was that you couldn’t talk about climate change! And GE was really invested in onshore wind and saw this new kid on the block, offshore wind.

So the three of us got together from these agencies and put together this document. This is all about process, but it’s important. Most people don't listen to the stories about how things get done and they just assume they happen like magic.

We put together a group of stakeholders that was incredible. We got marine biologists. We got avian experts. We got geologists. We got the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. We said, we need all of you to provide input. How do we do this the right way? And so there must have been 40 stakeholders, we held a series of stakeholder meetings.

And then, in the final document.…usually, there's a picture of at least, if not the president, the secretary of an agency, or the governor of a state would usually have their picture, right? Because this is a big deal, we're publishing this this document that's charting the course for a new industry in the United States. And none of them are in the document. The first name that shows up is Greg Watson. It was sort of like, if this works, we’ll then take credit for it, if this falls on its face, you’re done. Success in working in government, for me, meant that I’m going to take that risk because this is my opportunity to do something significant. The only risk is that I could lose my job-for us that was a risk worth taking. We gotta change things.

We did that, and we were able to come up and help jumpstart the policy and regulatory infrastructure for offshore wind, which I think makes what’s happening now possible. People said, you spent eleven years, and you failed. Cape Wind didn’t happen. But it did get permitted-there was value in working with the Feds on a permitting process. We learned a lot.

So that’s a long-winded way of saying, I’ve been lucky over the years to be in those positions at those times when something was happening, and I could be engaged trying to jumpstart something.

Let’s talk about the urban farmers markets in Boston—a wonderful example of a trimtab. In 1978, Massachusetts agriculture was on the skids. We were losing farms and farmland at an alarming rate. People were like, so what, we’re an industrial, technology-oriented state, if we have to import our food, so what. We were already importing 85 to 95 percent of our food. But fortunately we had a commissioner of agriculture, Fred Winthrop, who said, no, we can't let our agricultural industry and just disappear. And so he put together a blue ribbon commission that was headed by this guy, Ray Goldberg, who was head of the Harvard Business School. He said, I want you to pull together some people and come up with recommendations of what could we do as a state with our limited resources to save agriculture in Massachusetts. They were volunteers-this was a purely voluntary effort. They came forward with recommendations that were published, 22 pages, it was called A Policy for Food and Agriculture in Massachusetts. It laid out the scheme about what we could do.

The recommendations were straightforward but actionable. The first one: preserve what’s left of our prime agricultural land. We set up the Agricultural Preservation Restriction Program, purchase the development rights of farms being threatened by development. We said, we will pay the farmer the difference between the agricultural value of the land and what he could get if he sold it to a developer. Cash. The farmer still owns the land, but what we’ve purchased is the right to develop it. It will stay farmland.

So we had that program that preserved farmland, but then they said, what do we do to help preserve farmers themselves? One of the key ones was, direct marketing. We’ve got to find a way to put farmers in direct contact with consumers, and eliminate as many middlemen as possible. Deep down, systemically, what are we trying to do? Remove barriers between the farmer and the consumer. Let the farmer, make a decent living and actually prosper, let the consumer get healthy and locally grown food at an affordable price. At the time, it was in processors, distributors, and even grocery stores, that’s where most of the money was being made.

One of the recommendations was, let’s create farmer’s markets. There were rural farmer’s markets, we didn’t invent farmer’s markets, but we didn’t have urban-based farmer’s markets in Massachusetts at the time. The farmers needed some type of monetary benefit that makes it worthwhile. What that meant was, you need a large population center, you need to come to a place where you can sell a lot of produce. What the state will do is, we’ll set up the market site, all we’re asking you to do is come in and take advantage of this site.

So this was 1978 in Boston. There had just been court ordered busing to desegregate schools in Boston. Racial tensions were high. There were riots. I was working for South Boston High School, which had been forced to integrate-whole lot of tension. I was teaching, we had environmental programs on the Boston Harbor islands. A lady named Susan Radley, she came out to the islands and said, we’re setting up a new network of urban farmer’s markets. She said, would you like to help us organize that? I said, “I think so, Susan-tell me exactly what a farmer’s market is.” I could see it in my mind’s eye. I said yeah, I’ll do it.

The school year ended. We found sites-we got a section of Dorchester Avenue blocked off with the police, places for the farmer’s to drive in, I went out and recruited farmers. I got twenty farmers to say they would come.

July 8, 1978, Saturday morning in Dorchester. Streets blocked off. Lieutenant Governor Tommy O’Neill, was there, the Boston Globe, Channels 4,5, and 7. It was 9 o’clock we opened, ribbon cutting, not a single farmer.

9:10. Not a farmer.

9:20. A farm family comes rumbling down Dorchester Avenue in their pickup truck, Katchie Berberien, his wife Mary and daughter Ellen from Northborough, Massachusetts, loaded with vegetables. They didn’t even get a chance to set up-they were selling stuff so fast they never got off the truck!

That night, I was like, okay, this is going to look bad. I said, we’re going to fall flat on our face, one farmer showed up! But the TV camera took a close-up. Not a wide view. All you could see was the one farmer selling produce like crazy. Their fellow farmers saw that, and the next week we had twenty farmers in Dorchester.

They told me, “We were afraid. We thought if we came into the city and made a lot of money, we’d get robbed.” They would go to the wholesale market, drop off your stuff, get a check, and drive out of Boston. They were afraid, they didn’t know how to navigate. That was their perception of the city. And before we even set up that Dorchester market, we had to convince the city neighborhood folks why we should do this “to help these rich farmers get richer.” The consumers thought these were rich farmers, big combines. Almost none of them had ever been to a farm.

So there were misperceptions on both sides.

These markets became not just places where transactions happen, they were literally partnerships between the farmers and the consumers, the residents. Just one example: after the first market in Dorchester we set up markets in more affluent neighborhoods like Brookline and Newton. Some farmers would go to both of them, Because it turns out they were making a lot of money. There were huge populations. And then the farmers said, so we’re charging a little more in Brookline and Newton, and little less in Dorchester. Can we do that? It turns out that the folks in Brookline and Newton found that out and they were pleased.

There’s stuff going on, where if you only read that these farmer’s markets were set up, you don’t capture what these were about. These were about people who at first don't understand one another but then through the markets begin to understand.

Harry Currier was a potato farmer, from Orange, Massachusetts. Harry would come in, he came to the first market, all he had was potatoes. I said, Harry, is this worth your while? He looked around and he said, maybe not now, but then he realized, he said, that he grew only potatoes because before that, his only outlet was a wholesale market. And the wholesale market said, you're a small farm in Massachusetts. We can't spend time dealing with a little bit of this, a little of that. You bring in your potatoes and dump them and then get out of the way. To a large degree, the marketing system was set up to encourage monocropping if you're a small farmer. The only way you’ll sell your stuff is to have a lot of one thing. Maybe if you have a roadside stand, you can do other things. But all of a sudden, this farmer’s market option was a retail option for them. A variety of produce is attractive to your consumers, which means you’re probably better off to have a variety

Harry Currier, white farmer, his wife told him the first time he came to Boston, she made him buy a new straw hat because his old straw hat was so beat up. She said, you can’t go into Boston with a beat-up straw hat. That winter, he came to Dorchester for a farmer’s market planning meeting. One woman, a black consumer-this is a true story-said, can you grow collard greens in Massachusetts? He said, yes, I will grow collards, but I need to know that this market will be there, because the wholesale market isn’t going to buy them from me. And so there was nothing in writing, but there was this agreement, you understand, that you're telling us what you like and we're going to respond. And I could go on with other stories, but I point out that that happened.

The whole point here was once again systemic. We were looking for systemic change in the food system, like we were looking for systemic change in the energy system, with things like Cape Wind. For me, I’m an organizer. I don’t pretend to be an expert in agriculture, or an expert in energy-although what happens is that as a result of these experiences you do do develop a certain expertise. Yesterday I was just sworn in as a member of the Massachusetts Energy Facilities Siting Board.

Awesome, under Governor Maura Healey!

Yes, yes. It’s interesting, now I’m on the other side of the table. Now, I’m a regulator. We’re responsible for reviewing all of the major electricity facilities in Massachusetts. And that includes power plants, offshore wind farms, transmission, right, the whole bit. The goal is to do a more responsibly expedited permitting process. There are nine seats, including six ex officio government people and three public seats that are the environment, labor, and energy seats. I’m the energy seat on the committee. That’s an acknowledgement, them saying, we are committed to offshore wind, but the major challenge is siting them.

The big obstacle is NIMBYism, right?

It’s NIMBYism, and part of it’s economic-some of these companies are needing to renegotiate their power purchase agreements, costs have gone up. But yes, it’s NIMBYism and fear. We’ve got to figure out how to cut the time and the costs for siting.

I just need to mention the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative; it was a graduate course in community-building, and just in life. Dudley Street [in Boston] is a multi-cultural neighborhood: Cape Verdean, Latino, African American, and white. The connecting thread? Poor. They were in a neighborhood that suffered from white flight after the war, with the GI Bill that gave returning soldiers the funds to move to the suburbs. It went from middle working class to a poor community. The city of Boston had a plan for urban renewal, “this place has gone downhill,” almost everything was rented out by slumlords, the buildings were decrepit and falling down. The city said, we’ll put in marinas and condominiums, and the slumlords said, payday is coming, they’ll have to pay a pretty penny to get the land. The community looked at this plan and said, we don’t see ourselves in this. We have nowhere else to go. They were pleading with the new mayor, Ray Flynn. Ray Flynn had supported court-ordered busing. He was from the South End, the white community. His challenger in the election was Mel King, a black legislator from the South End. He just died recently. He was a Renaissance man, taught at MIT. He coined the term “rainbow coalition.” Mel was the first African-American to run for mayor of the city of Boston. It was contentious. He lost, and Ray Flynn in that process I think felt that he had lost the support of the black community, because of the way the campaign had gone. So when the community that saw this plan said, we need to meet with you, you need to stop this, he said, I’ll put a halt on this urban renewal project. When the speculators and slumlords heard that, they got fearful. Many of them burned their buildings down to collect insurance and minimize their loss. The place was reduced to 1,400 vacant lots. Burned to the ground. You could stand in the middle of the community, turn 360 degrees, and you wouldn’t see anything standing. The community felt that they weren’t going to leave, they were going to rebuild. They went to Mayor Ray Flynn, and he said, I’ll give you anything you need. The community had created a vision of an urban village, they had been consulting with environmental lawyers, who said the city needs to give you the power of eminent domain over all abandoned, vacant land. The land was vacant, rubble. It had never, ever been granted to a grassroots community organization, much less a multicultural organization! Mayor Ray Flynn held lots of negotiations, and then they granted them this power.

So they said, how do we develop this and build new housing? Because most people start to build their wealth through homeownership. But the pattern is you improve the neighborhood, homes go up and then taxes go up, and the next thing you know the people who were there and wanted to take advantage of it are priced out of their neighborhood. And they said, how do we prevent that from happening?

And it was decided that they create a community land trust. And that decisions are made not to maximize the benefit of any individual, but to maximize the benefit and the welfare of the community. And as a result, what they could do was put a cap on how much profit could be made over a certain period of time on the resale of any house within the land trust. Individual homeowners wouldn’t receive the maximum they could get if they sold their home, but you could also make it unattractive for speculators to buy it up and try to resell. And it worked. It worked. And so they rebuilt homes.

The Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative was established in 1984. I was executive director for four years (1996-1999), working with a thirty-member board of directors that met the first Wednesday of every month. Members representing residents, religious organizations, nonprofit agencies, local businesses, and community development corporations. In my four years as director we never failed to achieve a quorum. With community control of the land and transparent community governance, they knew that they had what it took to bring about meaningful systemic change, and they were more than willing to put in the needed time. The reality was this was a community led planning entity that redesigned their community and defied conventional wisdom of even the most renowned urban planners, who would say you can’t decouple gentrification and displacement, they go hand in hand. Is any community going to voluntarily limit the money they can make? To a person, they said yes we will, because I want to live here. The banks said, who’s going to accept a mortgage on these terms? And they were surprised. So it is an incredible story that I can't do justice to here.

Why hasn’t it been replicated? Because it was so successful! I don't think most cities would like to see giving that much power over to communities.

I have been truly blessed with the opportunity to be on the ground and see that systems change can happen. It’s almost always bottom-up. For example, Dudley said, we don’t need you to help us dream, but we are going to need your help on policy and financing. One of the projects we built was a 10,000 square foot greenhouse, right at the corner of Dudley and Brook Avenue. The community became the eyes and security for that greenhouse. Never vandalized.

The general point is, there are more options out there to get these things done if you’re willing to understand the power of cooperation. And to circle back, that’s what’s happening on the global scale, with these countries beginning to see the benefits of cross-border electricity trade. As we reconnect as a single species, we return with this powerful inventory of accumulated wisdom and knowledge about the planet that does allow us to be conscious, productive participants in the planetary evolution.

Wow. Thank you.

Thank you, Sam.