Learning from the Low Lands #1: A Utopian Floating Neighborhood in Amsterdam

The Schoonschip Project: sustainable societies seeding super-cool seaborne suburbs!

I arrived in Amsterdam on January 15th, 2024, beginning a journey through the Netherlands to learn more about this low-lying nation's pioneering relationship with water. How this trip came about was rather unexpected: I had been communicating with Dutch water management historian Johan Sturm to set up a Zoom interview for this newsletter, and at one point he suggested that I should attend a conference on Dutch water infrastructure held by the "Stichting Blauwe Lijn" (Blue Line Foundation) on January 17th. I almost reflexively demurred, but then it occurred to me: why not? While I was in the country, I could stop by several other fascinating projects that I’d learned about in recent years, often while researching stories for my newsletter. The Netherlands has long been at the cutting edge of human civilization's relationship with water.

So in mid-January 2023, I visited an array of fascinating “good Anthropocene” water management and sea level rise adaptation projects in the Netherlands, across a multitude of domains In this and following articles, I’ll share what I learned from the Schoonschip floating village, the Sandmotor project, the Blue Line Foundation conference at the Topshuis of the Oosterscheldekering (part of the Delta Works), the reconstructed Temple of Nehalennia in Colijnsplaat, and the floating dairy farm of Rotterdam!

I arrived in Amsterdam at the Sloterwijk station, and the first thing that struck me was the much commented upon non-car-centric urban planning and transportation infrastructure. Just outside the station was a vast field of parked bikes, next to a sleek tram heading for the city center. My thoughts on urban planning and in-city transit have more or less followed the trajectory described in this xkcd comic in recent years, so I quite enjoyed seeing that.

While walking towards the city center, I was pleasantly surprised by the abundance and species richness of waterbirds in the Amsterdam canals. In addition to cosmopolitan urban standards like gulls, pigeons, crows, starlings, and mallards, I saw while in Amsterdam a multitude of Eurasian coots, a colorful wood duck, several Egyptian geese, moorhens, and two majestic grey herons, as well as a few rose-ringed parakeets.

Along the way, I happened to pass the De Otter windmill, one of only five remaining of a once-common type of ingenious Dutch wind-powered sawmill. It seemed to be in the process of being restored.

During my trip, I read a fascinating political economy book, Pioneers of Capitalism, which highlighted the Low Countires’ early adoption of several market systems and technologies that came to shape the modern globalized world. For example, the Netherlands’ marshy landscape, particularly in northern regions like Frisia, gave them a comparative advantage in cattle herding compared to cereal grain agriculture, which led to relatively high trade in the early medieval period exchanging dairy products for grain from the Baltic plains.

Seeing the De Otter mill by chance with the early chapters of this book fresh in my head, I was reminded of the Terry Pratchett classic Men at Arms, in which the first-ever gun is invented on the fantastical Discworld. A character muses that a gun is fundamentally different than a sword, or even a bow and arrow, because it produces energy that can be used regardless of muscle power; an incipient energy transition. Wind and water power are early benign versions of that, gaining energy which can be used to perform useful work without cajoling or forcing a living being to use its muscles. An early step on the great civilizational meta-trend of ephemeralization, doing more with less, as advances in technology empower humans to use fewer resources to achieve more goals. And this clockpunk-looking wooden sawmill was at the cutting edge of all that in its day.

But as interesting as this was, it wasn’t the main reason why I was in Amsterdam. After grabbing a bite to eat1, I made my way to the day’s primary objective.

I was determined to see the Schoonschip Project.

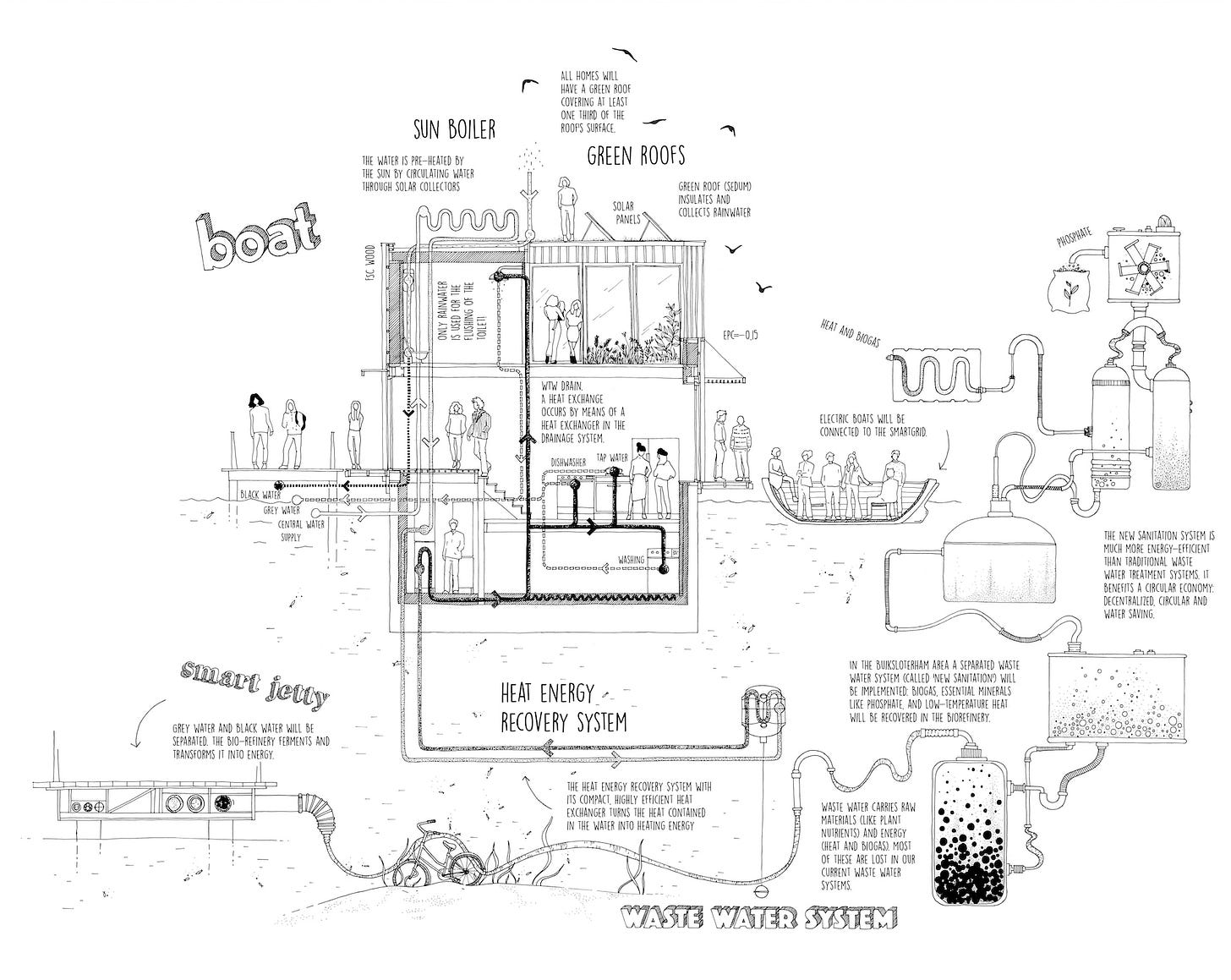

The story of Schoonschip is basically a Kim Stanley Robinson solarpunk novel come to life. In 2008, a group of friends came together with an audacious idea to pioneer a new way of living, and by 2020 they’d built a 46-household floating village home to 144 people. It’s about the most utopian, clean energy-powered, environmentally-friendly-while-maintaining-modern-high-living-standards place to live I’ve ever heard of! Schoonschip is powered by 516 solar panels (every house has its own big battery to ensure consistent electricity!) and warmed by 30 heat pumps (one for each floating “ark” some of which have more than one house on them), which are interconnected in a local smart grid.

The clean energy is just the beginning. Each roof is at least one-third covered in succulents, grasses, and mosses. All the houses have vacuum toilets, from which human waste is sent by vacuum tubes to a biodigester that extracts the phosphate for fertilizer. Floating gardens are home to local grebes, ducks, swans and coots. And that only begins to cover all the cool stuff they’ve done! It sounded like a pro-progress environmentalist’s dream.

I finally arrived at dusk, later than I had planned, owing to a series of entirely avoidable delays on my part involving an interesting flock of seagulls and an inauspicious choice of ferry. The experience of walking into Schoonschip felt like a fascinating mix of normally disparate experiences: one-third suburban housing development, one-third boat, and one-third wetland. From a distance, it was an assemblage of basically normal-looking, if sleeker and more futuristic than usual, suburban family homes. As I approached the dusk-limned floating houses, among the first things I saw were paddling swans and beds of cattails, with floating gardens between the houses at intervals hosting faintly audible waterfowl amidst reeds. Walking onto the intricate wooden jetty network that served the neighborhood as a sidewalk, I noted an eclectic mix of watercraft and landcraft: a bicycle learning against a wall near a surfboard, a stroller parked next to a hanging life preserver. The folks living here could jump out of the window for a swim in the morning, then bike into the heart of Amsterdam.

After a few minutes of strolling around and taking in the sights, it occurred to me that, since the Schoonschip visit had been a last-minute trip addition, I was basically about to knock on people’s doors as a total random stranger and ask them questions about their neighborhood. Even to me, with my social awkwardness senses atrophied by years of political canvassing, environmental activism, and independent journalism2, this seemed like it would come across as a trifle odd.

Interviewing Schoonschip Residents

Fortunately, I needn’t have worried: everyone I encountered was really nice. I asked variations on the same basic questions, standardized here for clarity, and had conversations with five households before night fell. In standard The Weekly Anthropocene interview format, this writer’s questions and comments are in bold, while Schoonschip residents’ words are in regular text and extra clarification added after the interview is in bold italics!

Manon:

Why did you move to Schoonschip?

I love it. There are a lot of reasons: It's not easy to find living space in Amsterdam, so building your own house can be cheaper. It's great living on the water.

Do you have any advice for future Schoonschip-type projects?

I'd advise them to look at the Schoonschip platform we had, not to give up, and to find a good group of people.

Lynn & baby Elua

Why did you move to Schoonschip?

We heard about it from friends. It started with a small group of people and kept expanding, so we were like friends of friends.

What’s in like living in Schoonschip, compared to a non-floating home?

It's amazing. Everything is different. We're a community, our values are aligned. It's like a village inside a city.

Do you have any advice for future Schoonschip-type projects?

Have patience. Strive for the best.

Noa:

Why did you move to Schoonschip?

The sustainable mission, and the community part. We're positively influenced by each other.

What’s in like living in Schoonschip, compared to a non-floating home?

Actually not so different, besides the lovely water reflections. And you can jump out of your house and swim! There are lots of kids playing, it's fun. Oh, and living closer with the waterbirds! Swans breed in the corner here. You can see the little ones, you can see the eggs hatch. You grow up with them.

Community is an adding element. I'm a lone mother, I have two kids. We support each other a lot!

What’s been your experience living in a floating house during storms?

Last week, my entry disappeared into the water. [The little sub-jetty3 linking Noa’s house to the main communal jetty looked like it had been recently replaced]. That also happens. The most important thing is the community living. We support each other.

Do you have any advice for future Schoonschip-type projects?

I think what is cool about this infrastructure is that we keep our own space, but have a community. You can contribute, but you don't have to. There's working groups and stuff, but you're not forced to be in a working group.

Marjon:

Why did you move to Schoonschip?

My studio is close by. [Marjon is an artist]. Four years ago, one of these floating houses came up for sale, and I thought, this is the place. Living on the water!

What’s been your experience living in a floating house during storms?

It doesn't matter. It's so nice to see the lamps swaying, the trees, the water. It's like a constant movie.

Do you have any advice for future Schoonschip-type projects?

We're on the forefront of all developments technically, so it takes a problem-solving and hands-on mentality.

Anything else?

I'm just happy.

Laurien:

Why did you move to Schoonschip?

The most pragmatic reason was I was recently divorced, I knew some people that lived here. I was one of the last people to jump on board.

What’s in like living in Schoonschip, compared to a non-floating home?

It surpassed my expectations! I think the reason is the amount of people. There's about 150 people here, like 47 or 45 households. It's the perfect amount to have a community, individualistic but with group support. We had to overcome obstacles together, we built this together, dealt with challenges together. That all makes you linked together. That's really cool. Most people here have a great sense of humor, they're ambitious, progressive, open-minded. I've made new friends. Many people here are quite idealistic, but we don't hold each other accountable too much. If you start to be judgmental at each other about what you're doing for the environment, it doesn't help. Not everyone has the same lifestyle. Some are strict, some are lenient.

It's really, really special. The guy from the notary said, when we weren't sure that the project would continue, he was amazed that so many people vouched financially for others that we didn't know. If too many people had stepped out of the project, it would have fallen apart. That's where the idealistic part has played in our favor. It was like, "this is crazy," but in the end, it worked!

Once a year, we have a community dinner, a long line of tables with white tablecloths [on the jetty]. We cook, there's activities, there's "Boat Camp," like boot camp, for people who work out on Saturdays. Only if you want, there's no social pressure. It's a beautiful balance. It really feels like living in a tiny village within the bigger city. In summer people go swimming, someone says "I'm making cocktails, who wants one" that kind of thing. I'm super proud that everyone is so willing to accept difference.

After a little while chatting with the inhabitants, I realized that the thing that was interesting me so much about the Schoonschip Project is that it appears to go some way towards solving more or less every major problem of modern civilization at once.

Concerned about climate change and disaster resilience?

Try living in a renewables-powered floating house that can easily ride out a storm!

Biodiversity loss?

Invite nature in, let the swans breed in the cattail beds in the corner, and incidentally build your houses and neighborhoods in such a way as to substantially reduce residents’ contribution to many of the major threats to wildlife, from climate change to air pollution.

The housing crisis, particularly acute in major urban areas in the West?

Build out onto the water, opening up lots of new living space right next to economic opportunity-filled cities!

The loneliness epidemic, a sensation of lost connection in an atomized increasingly- digital landscape?

Try living in a Dunbar's Number-compatible (aka "monkeysphere sized") urban village, with a strong community feel.

The difficulties of parenting and how many people feel they can't have all the kids they want to, as labor-intensive services like childcare grow harder to obtain? (As I’ve written before, I don’t think that lower fertility rates amount to a crisis, but this is where many people cite “the fertility crisis”).

In addition to better housing and community support, try living somewhere where your kids can jump off the front porch and swim over to play with friends! Schoonschip seemed positively filled with kids, a rarity in many developed-world neighborhoods these days. It looks like a great place to grow up.

By the time I left this fascinating floating village, I realized that I would absolutely love to be able to live in a community like Schoonschip in future years, and the more I thought about it, the more it seemed like a feasible prospect. For a start, to encourage others to follow their example, the Schoonschip folks have shared the lessons they’ve learned during the building stage on their beautiful Greenprint website!

The world is full of nice, sheltered bits of ocean near thriving cities, tucked in behind barrier islands or capes. I mused that in Portland, Maine, where I went to university, the inlet of Back Cove could likely support several Schoonschip-type villages, nicely tucked away out of the shipping lanes and well shielded from the open ocean. Perhaps a few on the leeward sides of some of the populated Casco Bay islands, too. Their ecological footprint would be nearly nil, with elevated jetties avoiding foot traffic damage to dune, salt marsh, seagrass, and dune habitats. Or indeed positive, with bivalves and seaweed colonizing the undersides of the floating homes and seabirds nesting in the floating gardens. It would help relieve the Portland housing crisis4. Really, the same model could be applied in almost any coastal city. New York and Boston Harbors, the sheltered sides of New Jersey, North Carolina, and Georgia barrier islands, San Francisco Bay, the Thames Estuary, the Venice Lagoon…the possibilities are exciting!

Most people would be happy to live a clean energy-powered, low environmental impact lifestyle, but many previous “environmental villages” projects haven’t made themselves attractive enough to become a scalable model; even interestingly innovative designs like the Earthship can come across as just too weird to become popular within existing cultural and regulatory structures. It takes a really dedicated enthusiast to live in an Earthship, but moving to a fully-fledged Schoonschip looks as easy as moving to any other housing development. By contrast, suburban homes (single-family, duplexes, triplexes, etc.) have stood the test of time as a popular component and symbol of an aspirational middle-class lifestyle.

Schoonschip seems to have found a brilliant way to integrate the best aspects of historical villages (accessible, walkable communities, a sense of “knowing your neighbor”), present-day suburbia (independent family spaces, proximity to cities), and future-proof resiliency (decentralized independent power, 24/7 flood resistance). The world needs more neighborhoods like it. This is an AWESOME idea, and worth spreading!

Reminded of the company’s existence by my own interview appearing on my phone, I used anti-foodwaste app Too Good To Go to order a "surprise bag" from an Amsterdam bakery, for a mere five euros. I was expecting a few leftover pastries, and glad of it, but I was given a gigantic amount of bread: five big loaves plus several bags of savory tarts! It was more than I could possibly eat; heck, it was so voluminous it was more than I could carry without awkwardness. I ended up eating my fill, keeping the one loaf that fit in my backpack, and hanging up the rest of the bread-filled shopping bag on a random apartment building doorknob. I'm pretty confident it won't go to waste. Perhaps someone will make bread pudding.

(I wouldn't normally share such a picayune personal experience, but I am genuinely really impressed by the Too Good To Go app. I try to spread word of its potential as a scalable solution to food waste, and hopefully play some small part in speeding its growth to become an Airbnb or Uber-like mainstay of digital modernity!)

My friends and family would testify that I can be gregarious to the point of outlandishness.

“Sub-jetty” is probably not the correct term here. I’m talking about the kind of little four-meter-ish footpath you normally see linking a house to the sidewalk, but here it’s linking a floating house to a floating jetty. Uh…deck? Bridge? Gangplank? Gunwale? Aqua-porch? Swimmer-shade?

Although any first-round Schoonschip-type homes would probably end up being pretty expensive to start with (at least before a standardized design is iterated), it would likely still help relieve upward pressure on rents by absorbing new residents, who would then be able to contribute to the city’s culture and economy without needing to bid up the price of existing housing stocks to buy a place to live. Here’s a great article on how new market-rate housing can help prevent working-class displacement.

I loved how you commented that this environmentally friendly solution seemed actually to be solving a lot of other modern challenges as well. My theory is that they all go together. Living with an environment that is not thriving creates a lot of other dystopian challenges for our nervous systems. So everything sinks together, or everything improves together. Thank you for highlighting this example of improving a lot of things at once!

Nice reading such enthusiasm about my county. These projects are indeed a pleasure and we have always worked together with the North Sea and our rivers. Building techniques to last the impact of the (salty seas) water are a build up experience for ages. We also have plenty of forested areas and I see developments of a like communities building up in these forested areas, where also balance is sought for living family lives in cooperation with nature. Exiting times, transition in practice :-)