The Banyan Tree of Aarey, the Kanheri Caves, and the WCS Macaque Project

Investigating India #2!

This is the second of my live dispatches from Anthropocene field reporting in India, chronicling my travel and research in this incredible subcontinent. Here’s an embed link to the first.

In this dispatch, I cover a hectic few days during which I experienced the magnificent banyan tree of Aarey (thanks to chance-met strangers), the awe-inspiring ancient Buddhist religious art of the Kanheri Caves, the fascinating WCS India macaque study in Sanjay Gandhi National Park, and more!

May 4, 2024: Aarey

On my first Saturday in India, after writing down some of my first impressions in the morning, I walked from my dormitory in the Marol Maroshi neighborhood of Mumbai towards the Aarey Milk Colony neighborhood (so named for its many dairy farms), where leopards have been regularly reported after nightfall. This was an

activity I’d conceived of earlier as a strategy for getting my bearings during my first days in Mumbai; I’d selected my lodgings in part based on the fact that they were only a few hours on foot from Aarey, and I’ve long felt that exploring a landscape on foot is perhaps the best way to gain knowledge of a place’s subtle uniqueness.

The day was scorching hot, and I thought I’d cleverly taken that into account by finding a mostly-tree-lined path to Aarey. But Google Maps had led me astray. (Google Maps seems oddly iffy in Mumbai overall; it had already sent me to the wrong bus stop). The path was walled off, and I unwisely opted to take a more circuitous route on paved roads instead of just hiring one of the many passing moto-rickshaws.

A few hours later, I was sincerely regretting my life choices. I’d passed many interesting things; a yet-to-be opened tree nursery-slash-art center, beautiful spray-painted animals and human faces on highway walls, construction sites, the back-alley byways of informal settlements, Coromandel herons pecking around the cows at the scattered small-scale dairy farms I passed. (I had thought they were cattle egrets at first, but iNaturalist told me differently based on the yellowish plumage on their necks). But it was hot. Really, really, really hot, and getting hotter. My hostel had no lockable safe or room door, so I had my entire “inventory” of travel possessions on my back, and the pack was feeling heavier and heavier. I hadn’t seriously backpacked in this kind of heat since one crazy day when was training for the Hundred Mile Wilderness in the lockdown summer of 2020. On that occasion I’d had emergency services called on me in Windham, Maine because someone assumed that anyone hiking on the side of the road when the thermometer was in the 90s Fahrenheit must have some kind of problem. When the fire department tracked me down that time and found me backpacking on a main road in the hot sun, they were very polite, but clearly thought I was literally insane or experiencing some kind of psychotic break, asking me a series of questions along the lines of “Do you know your name?” and “Do you know what day it is?” Years later, now in Mumbai, I was beginning to wonder if they hadn’t had a point.

I pushed on, through more informal settlements, buildings crafted with fragments of wood, metal, and plastic. At one point, Google Maps showed that I was passing a Lotus Lake, but it had gone dry; I saw only a barren brown expanse. In this part of India, trees lose their leaves in the dry season, not the winter, so most of the trees on the side of the road were leafless, providing only weak fragments of shade. I took breaks more and more often, clinging to these tiny patches. The sun beat down like a furnace. I was drinking through the water I’d brought faster than I had planned. As Kipling wrote, only mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun…I’m not an Englishman, but I am from an Anglosphere culture, and I had definitely failed to adapt my hiking plans to the circadian rhythms of the tropics.

Eventually, just when I felt that I was slow-broiling in my own perspiration, a car slowed down to give me a lift. They asked where I was going, and because “wander around to get a feel of the neighborhood-slash-habitat” doesn’t lend itself well to getting lifts, I selected a name I’d seen nearby on Google Maps that sounded interesting. “Aarey Vasundhara Eco-Village.” The three dudes in the car deposited me there, shared their water, laughed off my fulsome thanks, and politely refused repeated offers of payment. This was just one of many unsolicited generosities that I was to experience in India; some kind folks just want to help people.

After a much-appreciated pause at a roadside shop for refreshments, I simply walked into the adjacent “eco-village,” through an open gate and into an assembly of seemingly half-built wooden structures. The place reminded me strongly of the Madagascar Biodiversity Partnership’s reforestation nurseries; there were young trees being cultivated under the roofless wooden structures, I met a fellow watering some of them, who didn’t speak English but waved me on. Eventually I came to the main building, where I found five more friendly people who didn’t speak English, a lavishly decorated shrine to Shiva (that I later saw was lit up with flashing electric lights at night), and two cats. I kept walking into the woods and eventually ran into a guy named Sundar, who did speak some English and advised me to go see the banyan tree nearby.

The banyan fig tree (Ficus benghalensis) famously develops additional trunks to support its growing branches, allowing individuals to extend to prodigious size. This one grew in a lovely little patch of woodland, with a gurgling stream and rose-ringed parakeet calls audible just a quick stroll away from the traffic-laden road, and it was simply beautiful. From the first moment I saw the majestic tree, I wanted to climb it, and after getting a cosign that it would be OK to do so as long as I took my shoes off. I did so, placed my backpack on the ground, stepped up, and reached a good twenty feet high.

I was thinking myself quite the intrepid fellow when to my astonishment, I perceived Sundar in a branch at what seemed like three times my height, imitating birdcalls to get my attention. He urged me higher, and I obliged by ascending several branch-junctions more, but stopped well short of his dizzying heights. Then, to my utter astonishment, Sundar began a series of death-defying athletic exercises from his perch on the tip of the branch. Apparently just for my benefit, to impress and amuse a foreign stranger he hadn’t known existed until about ten minutes ago, he started doing pull-ups with the branch as the bar, his legs dangling over thin air with the ground a spine-snapping distance below. I urged him to be careful (I was really hoping the man wasn’t about to fall to his death in front of me, and it was beginning to look like a distinct possibility!), but he laughed and escalated his daredeviltry still further, standing on one leg in a yoga-like pose. Then, as I thought my jaw could drop no lower, he spun his entire body around and hung upside down from the branch by his feet, his entire body hanging in the air, and did…reverse open-air sit-ups? I’m not even sure what to call that. The guy must have had the abs of a Hercules, or perhaps more appositely a Bhima from the Mahabharata. One slip, one crack in the bark, one moment of failed strength or coordination, and he’d have broken his neck.

Eventually he returned to a seated position and we kept chatting, myself alternating between heartfelt compliments and equally heartfelt requests to please not do that again, Sundar telling me that he slept in the tree branches sometimes and felt incredibly happy to be there.

Eventually, we descended to the ground beneath the banyan’s sprawling canopy and met a friend of Sundar’s named Elijah Emmanuel, who had one of the most serene and calming personal affects I’d ever seen. He wore a bushy beard and a yellow bandana, had an intricate tattoo of a banyan tree in a traditional style on his arm, said he’d come from a Tamil Christian family but that Nature was now his God, urged me to chill out and relax more in life, and started talking about the banyan tree’s good vibrations and how love was the common language of every living thing. I was feeling like I’d wandered into a time warp and ended up in a 1960s commune.

Then, the forest sage added me on WhatsApp, shared his Instagram handle, and directed me to a YouTube documentary about his work. Elijah was the founder of the “Seeds of the Banyan” NGO (directly adjacent to but not the same organization as the Eco-Village), which led kids from local settlements into the forest to learn about music and nature, often around this very banyan tree. He’d become an activist on the side of the local Adivasi villages in the Aarey woodland who were fighting to avoid being displaced by proposed construction projects, earning the ire of his own ethnic-Tamil community who had migrated to Aarey for work. He told me how migratory birds from Sri Lanka came to this little patch in Aarey in the winter, and that everyone knew that leopards sometimes wandered around at night but that he didn’t think they were a problem. We concluded our conversation, I thanked him, and he advised me not to say thank you so much, but simply to stay silent and observe when good things happened. As anyone who knows me could predict, I’m afraid I’m not going to be sticking to this dictum!

In the few hours remaining before nightfall, I wandered around Aarey a little more, refreshed and rejuvenated from the banyan tree’s shade and coolness plus Sundar and Elijah’s interesting conversation. The neighborhood seemed to be on the way up economically, with haphazard tangles of electric wires and thin little water pipes testifying to the recent installation of key infrastructure service.

I paused for a moment in front of a well-stocked little pharmacy. This is the kind of place that has led to child deaths worldwide declining by half in the last decade; unassuming little storefronts in scrappy wood-and-metal shantytowns, making available the wonders of modern medicine with people who need them. H.G. Wells said that history was just a race between education and catastrophe. Sometimes I think history could also be viewed as a race between medicine and catastrophe, with all of education, politics, war, and economics as inputs to keep progressing on research to prevent human beings from dying pointless deaths. And humans are starting to take a lead in on that race, with mRNA vaccines for malaria being deployed across sub-Saharan Africa and incredibly promising early research on mRNA vaccines for cancer and heart disease, the two biggest causes of death in the U.S. Just for this visit to India, I’d taken an oral typhoid vaccine in advance and was taking an atovaquone-proguanil anti-malaria prophylaxis daily; within a few decades, it might seem just as easy to get protection from all coronaviruses at once or a personalized cancer vaccine that reprograms your immune system to fight a specific tumor. I can’t wait.

Aarey also seemed a very ecumenical neighborhood, with Hindu temples, Christian churches, and images of the spectacled visage of B.R. Ambedkar beside the Buddha. It occurs to me that my readers really deserve to know more about this person. In American terms, B.R. Ambedkar is sort of like what you would get if a major Founding Father like Alexander Hamilton or Thomas Jefferson, a transformative civil rights activists like Martin Luther King Junior, and a founder of a new religion like Joseph Smith were all the same person. Summarizing his life in a few paragraphs of a blog post is a titanic proposition, but here goes. Ambedkar was born into an “untouchable” Dalit caste, was among the first from his people to graduate university, and worked for years as a lawyer, activist, educator, publisher, and political leader doing stuff like “fighting for the right for Dalits to use community water sources like everyone else” and “winning a legal case that confirmed the right of non-Brahmins to criticize the social privilege of the high Brahmin caste.” He also wrote a book called Thoughts on Pakistan in 1940 that some credit as being one of the key factors convincing non-Muslim Indians to support the eventual partition of Pakistan from India in 1947. With Indian independence arriving in that year, Ambedkar led the committee drafting India’s first constitution (helping establish an “affirmative action”-like system for historically disadvantaged caste and tribes) and served as Law Minister in India’s first cabinet under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. And then, at the tail end of a subcontinent-transforming career in politics, he decided to found a new religion.

Ambedkar saw the horrifically discriminatory caste system as too deeply embedded in Hinduism for a reform movement to be possible, so Hinduism, at least for the Dalits, had to go. He critically analyzed Islam and Christianity before deeming them not up to the task (reportedly in part because Christianity had coexisted with slavery for so long in America), nearly chose Sikhism but backed out for political reasons, finally settled on Buddhism (process of elimination?), and unhesitatingly reshuffled and updated the philosophy/religion’s core precepts to meet his people’s needs. Ambedkar discarded the traditional Buddhist Four Noble Truths as “pessimistic” and added his own Twenty-Two Vows to the remaining Three Jewels and Five Precepts of Buddhism. Ambedkar’s last book, The Buddha and his Dhamma, completed just before and published just after he died of diabetes in 1956, is treated as scripture by millions of Navayana Buddhists today. A statue of him named the “Statue of Equality” is currently under construction in Mumbai; it will be taller than the Statue of Liberty when complete.

I frankly admire this utilitarian approach to religion: Ambedkar was seeking a social technology to psychologically and culturally liberate the Dalits of India from centuries of bondage, dispassionately weighed his options, and found one that worked. Navayana “New Vehicle” Buddhism, also known as Ambedkarite Buddhism, is now the fourth major branch of the religion, alongside originalist Theravada, tantric Vajrayana, and syncretized Mahayana Buddhism.

Ambedkar lived in Mumbai for years, and his cremated remains lie in a stupa near the Dadar beach. In just a few days, I’ve seen photos, homages, namesakes, and general honoring of Ambedkar all around Mumbai. In the poorer neighborhoods that I’ve visited so far, Ambedkar is particularly revered: I see his image on building walls, impromptu stone monuments, and places of worship. A truly extraordinary figure.

I came back to the banyan tree at dusk and slept that night suspended between two of its auxiliary trunks in my hammock, thanks to Elijah’s kind invitation earlier. The bird and insect calls of the woods mingled with loud music playing from a nearby house, road sounds, and the occasional passersby on foot. It almost felt like camping in a suburban backyard.

May 4, 2024: Kanheri

The next day, I woke up in the hammock in the banyan tree around six AM, and enjoyed watching the sky lighten. The tropical sunrise and sunset are so rapid that observing the sky almost feels (at least to my tech-inflected Gen Z mind) like watching a laptop boot up, or gradually levelling up its screen brightness when plugged into a charger. After resting a bit more and repacking my hammock, I took a motorized rickshaw to the gate of Sanjay Gandhi National Park (the world’s only wild national park within the limits of a mega-city like Mumbai, home base for the urban-exploring leopard population that ranges into Aarey!), then took the in-park bus to the famed Kanheri Caves.

Buddhism had spread rapidly through the Indian subcontinent after Emperor Ashoka’s conversion in the 200s BCE, a strikingly similar forerunner of Christianity’s spread through the European subcontinent five hundred years later in the wake of Emperor Constantine’s conversion in the 300s CE. The Kanheri Caves were built mostly in the “interregnum” between Ashoka’s Maurya Empire and the Gupta Empire of the 300s-500s CE. The complex consists of 109 caves carved into volcanic basalt1, excavated and decorated over centuries by communities of Buddhist monks supported by local kings and merchants. Most of the caves are viharas, plain and unadorned structures with perhaps a few benches, akin to the European “monk’s cell” tradition and described as “the monks’ living rooms.” The remaining few are chaityas, halls of worship, intricately decorated with carved statues of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, dancers, and apsaras (akin the nymphs of Greco-Roman mythology). The caves often bore inscriptions proudly recording the donor who had paid for specific features. Most of the inscriptions were in the Brahmi script, the same used by Ashoka’s pillar edicts, as Sanskrit only became dominant in the later Gupta Empire.

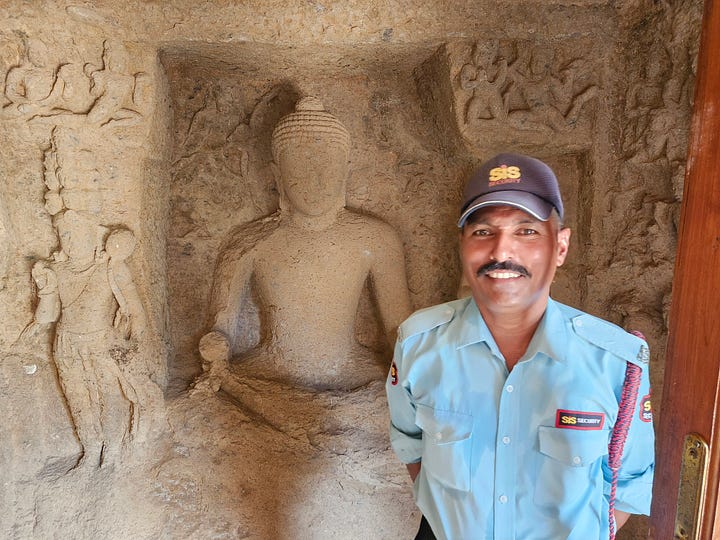

I saw the largest few chaityas first, including Cave 3, the largest and according to a sign “most impressive” of the complex, with two colossal Buddhas on either side of the entrance and a large stupa framed by columns in the deep recesses. Soon, a friendly Nepalese security guard named Rudrapata2 took it upon himself to give me a personal tour of the remaining highlights. Many of the caves have beautiful columns in front of their entrances, some round, some squared off, a few even octagonal. Cave 7 has a water cistern from the 100s CE, with an inscription recording that it was a gift of a lay worshipper. Cave 34 has a surviving painting of Buddha on the ceiling, the sheltered pigments having outlasted hundreds of years of weather, animals, and humans. Cave 41 has a carving of an eleven-headed Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, one of the only ones of its kind in India. Cave 90 has an inscription in Chinese on the wall by an unknown visitor. The Kanheri Caves were delved well before the famous journey of Buddhist monk Xuanzang to India in the 600s that inspired Journey to the West, so as far as I know we can only guess at the extraordinary journey the original writer must have undertaken.

Eventually, the caves’ shady, cool recesses become even more appealing to me than their historical treasures. The rivulet running through the Kanheri Caves had dried up; I would hear later that it formed a magnificent waterfall each monsoon season. Most of the Kanheri Caves complex is bare stone, and it was getting hotter and hotter. By the time my visit wound to a close every deep shadow had a few tourist visitors sheltering in it, with people crossing the baking-hot sunny zones as expeditiously as possible.

After touring the caves, I cooled down in the park canteen3, and soon noticed monkeys in the trees just outside the glassless (but barred) windows. There were two species present: the larger, long-furred, black-faced Hanuman langurs (Semnopithecus entellus, aka the northern plains gray langur) and the smaller, more numerous, pink-faced bonnet macaques (Macaca radiata). A Hanuman langur mother was nursing her baby just outside the park canteen window where I sat, and a smallish bonnet macaque climbed up to share the very same branch, even lightly poking the langur baby without stirring conflict.

Once the langurs left, more macaques moved even closer to the windows, climbing around and grooming each other on the buildings’ exterior metal superstructure. I was captivated by the personable little primates. At one point, three of them stiffened in unison and issued a shrill alarm call; I looked down to see that a dog was passing by. Eventually, the macaques even came right up to the windowsill bars, and I was impressed that the people in the canteen were observing proper “wild animal” encounter behavior: looking but not touching, taking pictures, and not feeding them.

…and then a few minutes later, a new couple came in and fed them a little. Sigh.

As I headed out of the canteen, to my great surprise, I saw some of the few people in India that I had already met in person; two of the WCS India researchers I’d met at the Mumbai Zoo. What amazing luck! I had known that WCS India were conducting a macaque study project in Sanjay Gandhi National Park, but I had had no idea that their macaque research was taking place anywhere near Kanheri Caves. Of course, I whipped out my notebook and immediately started asking them questions.

Vanishree and Sanyukta told me that despite prominently posted regulations advertising its illegality, people fed both the langurs and the macaques in the park, in the name of the god Hanuman. A prominent figure in the Ramayana with cameos in several other great Hindu mythological epics, Hanuman is a super-strong shapeshifting immortal monkey deity who loyally serves Rama, seventh avatar of the god Vishnu. The macaques are seen as being linked to the Vanar Sena, the Army of Monkeys raised by Hanuman for Rama on his campaign to rescue the goddess Sita from the rakshasa king Ravana. The langurs are believed to resemble the physical form of Hanuman himself, with their black faces and tails originating in the burns Hanuman suffered trying to rescue Sita himself. The date of the Ramayana’s composition is unclear, but believed to be in the 600s to 200s BCE range, so there’s over two thousand years of religio-cultural tradition here telling people that feeding monkeys is a noble and meritorious thing to do.

Not ideal from the perspective of reducing human/wildlife conflict, but then again, it could be much worse. I’d just seen a post on the global WCS newsroom warning of the threat to red colobus monkeys across Africa from the bushmeat trade and habitat destruction. India has relatively high monkey populations still, and their religious significance seems to me to be very likely a substantial net benefit to their survival overall. Keeping a pro-monkey attitude while continuing efforts to instill no-feeding habits would seem to be the best of both worlds, and that’s clearly what the park is trying to do.

I kept asking about the fascinating, playful monkeys, and the WCS researchers were happy to share more details. In the project’s study area, where we stood now, there lived a group of about fifty macaques, and approximately twenty to thirty langurs. This group had three to four dominant males (a position usually decided by fights), and the current “alpha” macaque was a notably pale individual. The researchers pointed out the dog I’d seen earlier, and told me of the vendetta between the dog and the macaque group. The dog came up from the park’s Adivasi villages to chase and bark at the macaques, but the monkeys seemed to give as good as they got, never having been caught and routinely harassing the dog with raucous alarm calls and chattering taunts. I saw a macaque hang upside down from a branch by its feet directly over the dog’s head, apparently just to tease. The relationship was described to me as as “not really a prey-predator thing, just playful fights.”

The macaques are even keeping track of the humans’ weekly schedule. On Mondays, when the park is closed and there are no food-dropping tourists, they don’t show up to the concession areas and instead stayed in the forest. In the Anthropocene, humans’ arbitrary seven-day weekly rhythms are beginning to be mirrored by wildlife; I suspect countless other examples exist around the world. Might be a good literature review topic for someone!

Just as this fascinating conversation wound to a close, my first stroke of luck led to a second. Vanishree told me that the folks operating informal concession stands around the entrance to the Kanheri Cave area were all Adivasis, from the indigenous tribal peoples who have special permission to continue living in their historic village sites within the park. Knowing of my writing interests, she suggested I interview them, and I of course jumped at the chance.

Interviews with SGNP Residents from the Adivasi Villages

In standard The Weekly Anthropocene interview format, this writer’s questions and comments are in bold, while Schoonschip residents’ words are in regular text and extra clarification added after the interview is in bold italics!

These interviews were possible thanks to the kind interpretation of Vanishree, who translated my questions from English to Marathi and the responses from Marathi to English.

Mangesh

How long have you lived in the forest?

Since ancient times, for generations. I like to stay close to nature, I don’t like city life. During the COVID lockdown, the city people were in trouble. I enjoyed being close to nature. And it’s cooler here than in cities. A benefit.

When did you last see a leopard?

Many times. After six PM, we see leopards. Once, my wife and I were at home, and a leopard came into our kitchen. We threw chairs and it ran away.

How do you feel about the leopards?

At night, when we go home after work, if we see a leopard, it’s like a refreshment.

Are there any problems that come with living alongside so many animals?

The only problem is with monkeys. They steal food. The leopards sometimes steal chickens and goats. But good with the leopard. They’re doing it for survival.

Anything else you’d like to share?

No.

Prema

When did you last see a leopard?

They’re always around at night. If I wake up at night, I might see one suddenly.

How do you feel about living in a forest with the leopards?

There’s no problems as such. The only one is that the markets are really far away.

Are there any problems that come with living alongside so many animals?

They don’t really trouble us.

Anything else you’d like to share?

No.

Sunekha

How long have you lived in the forest?

I was born here in the forest.

When did you last see a leopard?

Two days back, around my house.

How do you feel about the leopards?

I’m not scared. We’re used to it.

What is it like living in the forest?

When we go out to the markets, even for an hour or two, we want to go back [to the forest].

Are there any problems that come with living alongside so many animals?

I don’t face any trouble [from them]. It’s nice to be around them.

Anything else you’d like to share?

No.

Deepak

How long have you lived in the forest?

I was born in the national park.

When did you last see a leopard?

Fifteen days. Outside my house.

How do you feel about the leopards? Are there any problems that come with living alongside so many animals?

They’re not scary. They’re interesting.

What is it like living in the forest?

It’s a very nice place. We are born here, so it is the place we like. I’m 49, but I’ve been living in the forest, so I don’t feel 49. The air is not as polluted here.

Anything else you’d like to share?

My son is 23, studying mechanical engineering, and my daughter is 21, learning architecture.

These on-the-ground interviews connected to so many broader trends I’d been reading about: social license for wildlife, the urban island effect, the Covid “anthropause” pushing people to reevaluate their relationship with nature, species becoming more nocturnal as an adaptation to a hotter planet. (In cooler climes, leopards are more diurnal; here they come out at night, and that will likely become common across more of their range as the world warms). I was fascinated to see such crystallization of global dynamics here.

I left Sanjay Gandhi National Park positively elated. In a patch of woodland almost entirely surrounded by a gigantic resource- and land-hungry megacity, an extraordinary equilibrium has been created, with a high-density leopard population surviving and even gradually increasing in an intimate coexistence overlapping with human-dominated landscapes. If Mumbai can pull this off, maybe anywhere or everywhere on Earth can! I see this as an incredibly hopeful exemplar of wildlife-human coexistence in the Anthropocene. Long may it continue!

That basalt, incidentally, erupted from the Deccan Traps super-mega-volcano, a large igneous province underlying much of what’s now southern India that may have contributed to the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event that killed the non-avian dinosaurs. The latest research seems to confirm that the Chicxulub asteroid impact was definitely the “death blow,” but the Deccan Traps was erupting over an area about the size of a small country at about the same time, likely making the asteroid’s impact worse. At the Kanheri Caves, I was walking on the cooled remains of Cretaceous lava flows.

Rudrapata told me that he spent six months working as a security guard in India, then the other six months in Nepal with his family. Remittances from such semi-regular migration and employment flows are a vital driver of economic development in many countries.

Pepsi appears to have somehow obtained absolute market penetration in India, at least based on what I’ve seen so far in Mumbai. Every other restaurant serves Pepsi. Ads for Pepsi are everywhere. The official park canteen sold Pepsi and was blanketed with Pepsi imagery. Even the tiny roadside stalls made from wood and metal scraps sell Pepsi. I haven’t yet seen a single trace of Coke.

Great travel Journal, Sam my take-away is from one of your observations, "This was just one of many unsolicited generosities that I was to experience in India; some kind folks just want to help "

That's been my experience also from personal experience. They are a very kind people on the whole.

Fascinating! Thanks for the write up.