Investigating India #1: First Impressions

A stream-of-consciousness report from my first few days in India!

First Impressions

The first thing I saw from Indian soil was an array of solar panels, visible from the window of my just-landed plane in Delhi (I had found cheap tickets to Delhi and would take a transfer flight to Mumbai), The airports’ aesthetic was a very familiar “globalized capitalism” one, with smooth minimalist design, “blobjects,” and a mall-like food court near the departure gates, but even in this homogenized hub, the content was becoming distinctly unfamiliar to me, redolent of rapidly industrializing and increasingly prosperous India1. I saw huge banner ads for appliances from Vijay Sales, a Best Buy-like retail chain I’d never heard of before. The card readers at the airport restaurants bore the logo of Indian fintech company Paytm. Chinese EVs, made by the increasingly globally dominant BYD company (still import-banned in the USA) stood shinily in one corner. A TV discussed the latest election results from Gujarat with the chyron BATTLE FOR BHARAT, and another played a dramatic high-production values ad for JINDAL: THE STEEL OF INDIA. When had I last seen a steel ad on American television?

Once I landed in Mumbai (aka Bombay: many people I met still called it that2), I waved off the offers of a cab or rickshaw and walked to my Airbnb-booked dormitory. That night and the next morning, my first impressions of the city were a pointillistic palimpsest of past, present, and future urbanism. Mumbai is famously a mosaic of income levels, architectural styles, and public service reliabilities, agglomerating organically with titanic modern buildings and highway flyovers right next to densely packed tenement-like neighborhoods. Some cultural aspects were quite unexpected: on my way from the airport to the hotel, I heard a stereo playing loud, upbeat, vocals-heavy “dance floor-like” music emanating from lit windows and thought “nightclub.” As I got closer, I saw the saffron paint and icon of Ganesh, and revised my assessment to “temple.”

The air pollution wasn’t nearly as bad as I’d expected: my eyes stung a bit sometimes and my glasses seemed to always need cleaning, but that was all. By contrast, the infamous Mumbai traffic was much worse than I expected: there seemed to be no traffic lights anywhere, only a very occasional lane divider or crosswalk, and every driver basically did whatever they felt like at any time. Horn noises were a constant. At one point, I asked a traffic policeman how to cross the street safely. He shrugged and said “Jump?”

It would have been easy to just focus on the things I saw that conformed to traditional stereotypes about India; there was a cow in the street across from my hotel, feral dogs and cats were a common presence, plastic trash piled up in corners. But I’d seen the statistics on how fast India was improving its citizens’ quality of life, and I could see a lot of evidence of a growing, progressing society on the ground as well. The streets swarmed with cars, bikes, motorbikes, three-wheeled motorized rickshaws, and embattled pedestrians, but I didn’t see a single old-style human-powered rickshaw anywhere. Some of the buses whizzing by were fully electric. Several construction sites had signs on the side boasting that a new stop for the nascent Mumbai Metro Line 3 would soon arise. Near the center of town, cranes hovered around growing skyscrapers. I could count the number of times strangers asked me for money on one hand: far, far, less than I’d experienced in Madagascar, and a similar rate to some American cities’ panhandlers. Smartphones were seemingly everywhere. On the outskirts near my dormitory, only a few hundred meters away from where I saw the cow in the street, I found an air-conditioned café selling delicious Western-style coffee and pastries, which is where I’m finishing up this first article now. Maharashtra, the state where Mumbai is located, has seen a substantial drop in child deaths in recent years thanks to spreading public health initiatives, with the infant mortality rate dropping from 19 per 1000 live births in 2018 to 16 per 1000 in 2020. Life is getting better here.

Bright and early on the morning of May 3, my first full day in India, I took the Mumbai city bus to go to the delightful Mumbai Zoo, where I met up with the Wildlife Conservation Society India team!

After several Zoom calls and considerable correspondence, I got to meet “face to face” Mumbai leopard experts Dr. Vidya Athreya, who I had the honor to interview, and program head Nikit Surve, who’d advised me on when to come to Mumbai. They were all at the zoo as part of a public outreach campaign about coexistence with Mumbai’s semi-urban leopard population (a vital conservation activity in the Anthropocene!) teaching passersby about the leopards’ biology and habits, their research methods, and avoiding conflict.

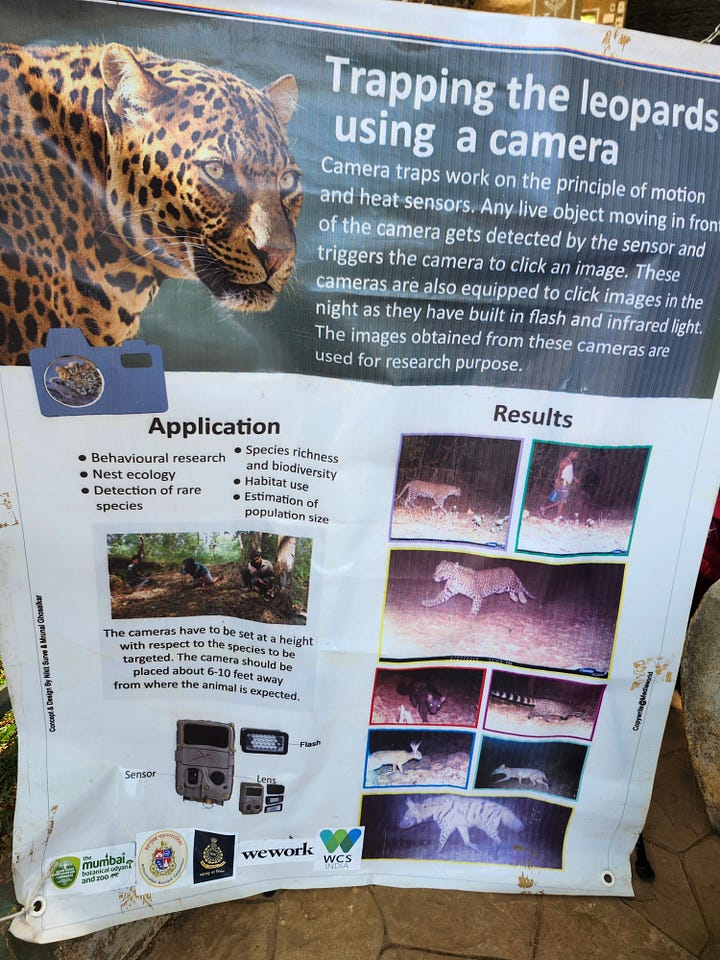

Throughout the day, I had the privilege to accompany them and discuss their work. They’d set up tables discussing difference aspects of the conservation program, with a radio-collared stuffed animal, a “drawing leopard rosettes” game, examples of camera traps (two infrared, one live, and one brought in from renowned big cat conservation NGO Panthera), blown-up photos of individual leopards and artistic illustrations of leopards’ presence in other areas, and more. Some of the camera trap photos were really striking; one showed a wild leopard rolling over on its belly to greet a barn owl, just like a housecat rolling over to play with a human. An apparent interspecies friendship between two very different predators, caught on camera!

I talked the most with Virendra Naidu, whose thesis defense was in two weeks. He was from the Pune area, where some of Dr. Athreya’s early “leopards in human dominated landscapes” research had taken place, in the very different context of dense agricultural sugarcane fields as opposed to Mumbai’s urban-woodland interface. Abundant black kites circled above the zoo alongside crows and the occasional parakeet; Virendra told me that vultures had once been as common, until diclofenac use led to sudden mass poisonings and a precipitous population drop.

Virendra emphasized the human-wildlife context was very context-specific, shaped by the unique features of each landscape. His thesis was on his research in the nearby Tungareshwar protected area north of Mumbai. Sanjay Gandhi National Park, practically within the city itself, had one of the highest leopard population densities in the world, but it was unclear if they had enough landscape connectivity to disperse to Tungareshwar, or what the predator situation was like in Tungareshwar at all. In addition to accumulating data on leopard presence, he was researching small carnivores as well, from jungle cats to civets. His early results had found that small carnivore presence actually seemed to be more common closer to human settlements, perhaps due to direct and indirect “human subsidies” like food waste and food waste-eating rodents. He was careful to emphasize that this data preliminary and unpublished; all they really knew was the spatial overlap, not the whys and hows of the situation.

Orvill had joined WCS only recently, but had previously worked for several other conservation organizations around India for many years; in Buxa Tiger Reserve, studying the nilgiri marten in Kadumane, and as a field biologist in Maharashtra’s Sahyadri Tiger Reserve. At the moment, he was focusing on reports, communications, and new research proposals for the two active WCS conservation and research projects in Mumbai, the Leopard Project and the Macaque Project. They’d just wrapped up a Jackal Project, noting the surprising presence of golden jackals in the mangroves shielding some of Mumbai’s watery edges.

Ishani’s Master’s was in microbiology, but she’d always been fascinated by wild animals as well, and had learned of a job opening at WCS from her former undergraduate classmate Vajnashree. She was now a research associate working on everything from project administration to field work. She was also the first person I met on the trip to organically bring up climate change, noting that Mumbai had had an unusually hot April and that there had been unseasonal rain reported in the Punjab. The mighty monsoon normally would come to Mumbai in mid-June, but there was now widespread concern that it might do something unusual this year, affecting the daily lives of hundreds of millions of people. I brought up India’s massive solar buildout, including the world’s largest solar farm under construction, and she agreed it was good but cited the classic intermittency problem.

I spoke to all these WCS personnel in the lulls when they weren’t educating zoo-goers. When they were thus nobly occupied, I got to explore the zoo itself, where by far the most impressive (and most popular) exhibit was the large enclosure for three royal Bengal tigers. There never failed to be a vast throng of people in front of the tiger exhibit, and I was attracted to it for a second visit when I heard a rising hubbub of excitement notable even from a distance.

Two of the tigers had gotten up from their doze in the shade, and one was approaching its pool of water, heading towards the human-visible side of the enclosure as it did so. A huge cheer went up when the tiger finally slid into the water, approaching the increasingly populous and excited crowd. It felt like a concert or a sporting event; people were lifting their kids up on their shoulders to see better, brandishing serried rows of supercomputing smartphones to immortalize the moment. I was heartened to see such manifest public enthusiasm for wildlife. Of course, the tiger is India’s national animal, but I somehow doubt that you would see quite this level of full-throated cheering in an American or European zoo even for a close encounter with a bison or bald eagle. It’s always tricksy to anthropomorphize, but I could have sworn that the tiger enjoyed the attention, swimming back and forth multiple times right on the other side of the glass wall from the adoring throngs of primates and even stopping in the middle to preen for a moment as cameras excitedly clicked.

This phenomenon wasn’t just limited to the zoo; India is one of the most tiger-friendly countries in the world. Tigers remain threatened by the voracious illegal wildlife trade, and have suffered greatly in the Anthropocene so far. The Bali, Java, and Caspian tiger subspecies went extinct in the 20th century, and the South China tiger subspecies is probably extinct in the wild. Tigers went locally extinct in Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam just in the 2010s and 2020s. But despite all this, today is the best time globally for wild tigers in years. The WWF reports that there were an estimated 5,574 wild tigers worldwide in 2023, in habitat patches from Siberia to Sumatra, up from about 3,200 in 2010; a 74% increase. And that’s mostly thanks to India! The latest Indian tiger census (also released in 2023), recorded 3,682 wild tigers as of 2022, up from 2,967 in 2018 and just 1,411 in 2006. Thus, most of the world’s wild tigers live in India, relatively protected from poachers and with a growing population. (Bangladesh, Thailand, Bhutan, and especially Nepal have also done very well protecting their tigers, but they’re smaller countries with correspondingly smaller tiger populations). With a rapidly developing population of over 1.4 billion people in a land area smaller than the continental United States it’s kind of amazing that India has any big cats left at all, but it’s managed to become a vital safe haven. If India had Vietnam’s, Cambodia’s, or China’s tiger protection policies (or rather lack of them), the entire majestic species might be teetering on the edge of extinction in the wild worldwide.

At the end of the day, WCS India’s International Leopard Day public outreach campaign packed up its tables among the exhibits and moved to the zoo auditorium, where a troupe of actors had donated their time to put on a play about conservation. Entitled “Sangeet Bibat Aakhyan,” roughly translatable as “The Leopard’s Tale: A Musical,” I very much enjoyed the spectacle. Even though it was in Marathi and I couldn’t understand the dialogue3, the dancing, singing, live music accompaniment, costume design, laugh lines, and emotive performances were fascinating in their own right. It was interesting to see what bits in English: every so often in the middle of a flowing Marathi sentence I’d hear phrases like “Wildlife Protection Act,” “Nice to meet you,” “You are not alone,” and for some reason “Jingle Bells.”

I’ll be spending at least the next five to seven days in the Mumbai area before moving on, and I have a lot of plans! Next up, I’ll be hiking through Mumbai’s Aarey neighborhood (where leopards are sometimes seen roaming into the city at dusk!) and the adjacent Sanjay Gandhi National Park!

My Inventory

One large blue Osprey hiking backpack. Everything I’m traveling with fits inside it. It makes me feel a bit like a video game character with a portable “inventory,” traveling around India with all my current possessions on my back!

One smaller green daypack that fits neatly within the blue Osprey pack, and serves as an extra layer of protection for fragile things like electronic devices.

Bathroom stuff: deodorant, toothpaste, toothbrush, and meds, including anti-malaria prophylaxis pills (good old atovaquone-proguanil, the same as I took for Madagascar), and some emergency antibiotics I hope I won’t need.

Some clothes (mostly T-shirts and synthetic shorts – it’s hot!), including a raincoat in case the monsoon comes early.

Several paper notebooks.

One pair of well-used hiking boots.

One LifeStraw water bottle, with a top-notch water filtration straw. Very useful already, as Mumbai’s tap water has an infamous reputation.

One hammock with mosquito netting, in case I get the chance to sleep outside at some point. Sleeping on the ground is not recommended: the WHO reports over one million cases of “snakebite envenoming” each year in India, although most are nonfatal thanks to modern medicine.

Devices: one phone with which I’m taking all my pictures, one Kindle Paperwhite on which I’m reading India: A History by John Keay, one laptop on which I’m writing these words, one backup battery pack, and charging cables & adapters.

My wallet and passport.

My glasses and some extra contact lenses.

Some extra plastic bags for if (when) I need to segregate wet or dirty clothes from the rest of the backpack.

It’s really quite easy to pack and carry, all things considered! It’s only been a few days, but this definitely feels like enough for my planned month-long trip.

This is a very rough “first impressions” dispatch from my first few days in the country; I’m incredibly excited to continue traveling through, learning about, and writing on India!

The “bestsellers” shelf in the airport bookstore contained a lot of books on politics, economics, and technology with relatively few novels. The overall tone seemed to be a proactive optimism with a strong flavor of national pride: the fantasy section included an adaptation of the mythological character Sita by a figure quoted as “India’s Tolkien,” the business section included an advice book called Do Epic Shit and its apparent sequel, Get Epic Shit Done. It’s currently Indian election season (2024’s is the largest election ever held, in the world’s largest democracy) and both the BJP and Congress seemed well represented: I saw a laudatory book on former Congress PM Rajiv Gandhi, a book on his son and current Congress party leader Rahul Gandhi’s recent pre-campaign walk across India, a pro-BJP paean called Modi 3.0, and a thick graphic novel entitled 100 Reasons to Vote for Modi. I picked this last one up and flipped through. It had a very different style than American political campaign books, combining earnest discussion of substantive policy points with rather embarrassing rhyming couplets in English, all on a background of video-game like aesthetics, references, and designs. For example, one page read “ACHIEVEMENT UNLOCKED: The Female Labor Force Participation Rate Increases BY 4.2% to 37.0% in 2023!” and another (of Modi) “He’s the ambassador of Indian culture’s zest/Gifting Bhagavad Gita, he brings forth the best.”

(Note: Indira, Sanjay, Rajiv, and Rahul Gandhi are no relation to “Mahatma” Mohandas Gandhi, who was famously a celibate ascetic. Yes, it is a bit confusing: India had a world-famous independence leader named Gandhi, and then a completely different family established the Nehru-Gandhi political dynasty, which has produced three major Indian Prime Ministers, two of whom were eventually assassinated, out of only 14 total PMs since India’s independence in the 1940s. In American terms, it’s like if the Kennedys, Clintons, and Bushes combined were all one family called Washington, but weren’t actually related to George Washington).

“Bombay,” the old name, is possibly from Portuguese and possibly a Portugal-ization of a preexisting local name. It was the name of the city for centuries, from Portugal’s early trading post through the British Raj and the early years of independence. “Mumbai,” the new name, is possibly the original Indian name of the place, though this is contested.

I was the only foreigner there, and several people wanted to take selfies with me afterwards.

Very interesting first impressions! I have never been to India, though my sibling has spent time in Pune, Nashik, and Kolhapur and flew in through Mumbai.

Looking forward to more updates and insight!

I love this stream-of- consciousness report, surprisingly easy to read. In big contrast to other text written in this style. Maybe it's more structured that the usual stream-of- consciousness reports.