Book Review: Sovietistan by Erika Fatland

A fascinating travelogue through an underreported region by a brilliant writer

I’ve always been fascinated by the “Stans” of Central Asia, perhaps since I was an atlas-obsessed kid who noticed that these countries took up a lot of space but that Americans heard very little about them. The Stans aren’t really big or populous enough to hold down their own “regional studies” field like Europe or Africa or India or China, at least in English-speaking academia. But they’re just fascinating, the crossroads of history, traversed by Silk Road traders and Tang Dynasty outriders and Mongol hordes and Romanov Russian conquerors, the home of great lost civilizations from Khwarezm to the Sogdian city-states.

Norwegian anthropologist and writer Erika Fatland’s Sovietistan, part travelogue, part hard-hitting journalism, and part modern history lesson, is by far the best book about this complex and little-known region that I’ve ever read. Ms. Fatland has an absolutely brilliant prose style, deeply erudite and knowledgeable yet simultaneously light and playful, subtly funny without becoming inappropriately flip. Reading this book in December 2023 directly inspired my January 2024 interview and article on the valiant USAID attempt to restore some of the Aral Sea ecosystem.

Restoring the Aral Sea!

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is working to help fix a Soviet-era ecological disaster in Central Asia, the infamous drying of the Aral Sea. The Weekly Anthropocene explores the story in this exclusive interview with Kevin Adkin, a USAID Regional Environment Specialist posted to Kazakhstan.

One key point that this book really hammered home for me was that the Soviet Union was just an objectively insane thing to have happened. I’m not talking about an ideological or ethical sense of “insane” here (though those may well apply), just the sheer implausibility of Soviet history! As of, say, 1905, before Stolypin’s last-ditch reforms fostered a shaky semblance of modernity, Romanov Russia was one of the most autocratic and reactionary and just generally “not with up with the times” powers on the face of the earth, woefully behind Britain and France and Germany and America and (as the war over Manchuria showed) even just-a-few-decades-past-medievalism Meiji Japan in geopolitically and industrially critical technological fields from physics to chemistry to engineering. In the next fifty years, it would suffer a grinding trench-by-trench war with Wilhelmine Germany, then a revolution and a fratricidal civil war, then rule by Stalin intentionally killing off multitudes of its own people at the same time as a global Great Depression, then an even more devastating war against Nazi Germany.

Then, less than two decades after that existential nationwide bloodbath ended, the USSR was the first country to put a human being into space! And was able to sustain a multi-year rocketry-powered Space Race and multi-decade nuclear weapons-powered Cold War with the U.S.A., a country that had been an ocean away from the worst battlefields of the World Wars and was much richer and more technologically developed to start with. What?! If that had happened in an alternate history’s geopolitics-simulating video game, or was published by some prophetic 1890s novel, it would come across as absolutely absurd, unbelievable on the face of it.

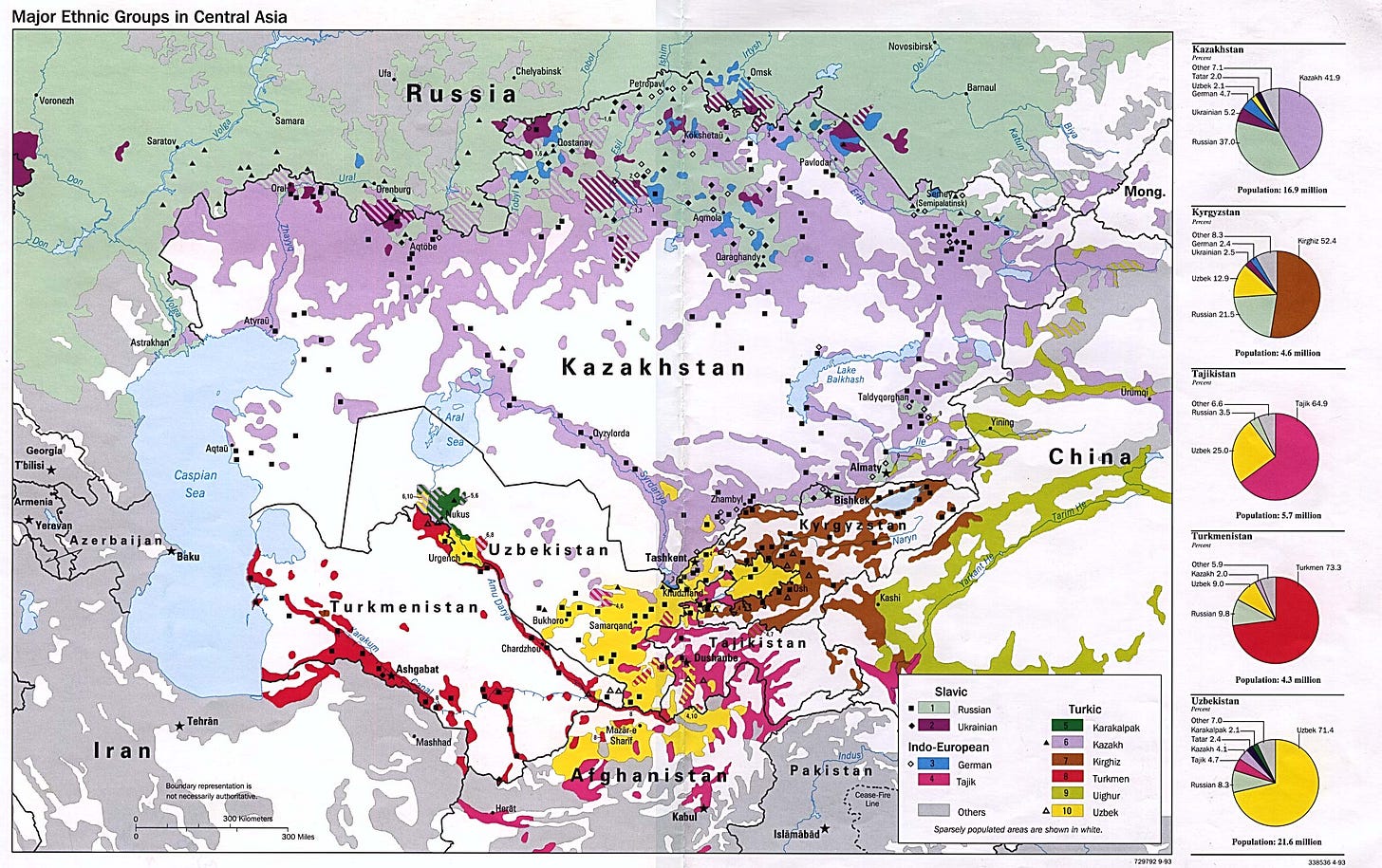

Obviously, none of that makes the horrors of the gulag or Stalin’s weaponization of famine to murder millions of Ukrainians in the Holodomor or the monstrous Beria’s sadistic secret police at all okay in the slightest. And Sovietistan doesn’t shy away in the least from the atrocities committed by the USSR, which many chapters discuss in painful yet illuminating clarity. Much of Central Asia was irrevocably transformed by mass famines caused by the senseless collectivization of farmers and attacks on increasingly imaginary “rich peasant” kulaks. The already-kaleidoscopic mix of local ethnic communities now includes people with roots from Germany to Korea who are the descendants of refugees dumped on freezing steppes due to Stalin’s policy of mass deportations.

To be even more clear, the Soviet Union was really extremely very bad and this writer rather thinks that it gets a portrayal in modern popular culture that is much more positive than it deserved. The USSR is all-too-often portrayed as a semi-comedic defeated adversary ripe for “radical chic” re-imagining instead of the totalitarian atrocity mill it was. There’s a strong moral case to be made that displaying the hammer and sickle from the flag that flew over the Holodomor should be as broadly condemned as displaying the swastika from the flag that flew over the Holocaust.

And yet, even given all that, even though in Central Asia alone the Soviets were directly responsible for mass famine, mass deportation, omnipresent state-sanctioned brutality, crushing of traditional cultural heritage, and drying up the Aral Sea…one of the most consistent trends that Ms. Fatland sees across the ‘Stans is a strong and pervasive sense of nostalgia for the USSR.

Why is this? I think it’s because, unlike Eastern Europe which was well into the Industrial Revolution and its consequences before being conquered by the Soviets, much of Central Asia went straight from “pre-Industrial Revolution, subsistence agriculture or nomad pastoralism-level standards of living” to “Soviet dominion.” And the benefits of post-Industrial Revolution technological civilization are so profound, especially for women1, that even when brought by a brutal mass-murdering dictatorship they can reasonably inspire substantial loyalty (and eventually nostalgia) for the regime associated with their introduction.

In Kyrgyzstan, Ms. Fatland interviews victims of and campaigners against the practice of “bride stealing,” which was legal until recently and is still disturbingly widely practiced. It’s exactly what it sounds like: men were allowed to kidnap women off the street, who were then considered legally their wife. The family are then expected to come to the wedding and be happy about it, with little chance of ever getting their daughter back. It’s just as vile as it sounds. That’s “traditional cultural heritage” at the sharp end: an atrocity that’s been around long enough that society’s grown to accept it, like a tree around a barbed wire fence.

One of the starkest parts of Sovietistan is when Fatland sneaks into the isolated dictatorship of Turkmenistan (which normally doesn’t let journalists in) by claiming to be a student. Outside the marble-clad, statue-studded natural gas-funded, world record-obsessed Potemkin capital city of Ashgabat (a darkly fascinating place in its own right), she ends up in a remote village living in extreme poverty, where the lifestyle hasn’t changed much since the Middle Ages2. Life is a never-ending succession of body-disintegratingly hard work just to stay alive. In a heartbreaking scene, she meets a young girl who is driven to write poetry about the beauty of the landscape around her in moments of time snatched from back-breaking farming and herding labor.

When people in developed countries opine on the downsides of technology and the stresses of living in the modern world, that’s the kind of thing that we forget. If you have the literacy and free time to read these words, you’re an elite aristocrat by the standards of most of human history. Again civilizational mega-trends like that, the rise and fall of even the most world-shaking of empires can appear small.

You can call human civilization on Earth in the 21st century many things — a wonder filled with horrors, a horror filled with wonders — but one thing Erika Fatland’s writing shows is that you cannot reasonably call it boring. Check it out.

In fact, as this part of Central Asia was devastated by the Mongol invasions of the 1200s, rural Turkmenistan is one of the very rare places on Earth where there’s a decent case that life might have been better in the Middle Ages, as the 1100s were the golden age of Merv and Khwarezm.

Fifth paragraph up from the bottom, “especially for women”.

Anyone: where is the first footnote denoted in the text?