Restoring the Aral Sea!

An interview with USAID's truly epic Environmental Restoration of the Aral Sea project

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is working to help fix a Soviet-era ecological disaster in Central Asia, the infamous drying of the Aral Sea. The Weekly Anthropocene explores the story in this exclusive interview with Kevin Adkin, a USAID Regional Environment Specialist posted to Kazakhstan.

In the interview below, this writer’s questions and comments are in bold, Dr. Adkin’s words are in regular text, and extra clarification (links, etc) added after the interview are in bold italics or footnotes.

I'm fascinated by the history, geology and geography of Central Asia, and I’ve read a good deal about the region. But for someone who who hasn't heard much about it, could you just give sort of a summary for readers of where the Aral Sea is, what happened to it, the diversion of the Syr Darya and the ecosystem collapse, and where we are now?

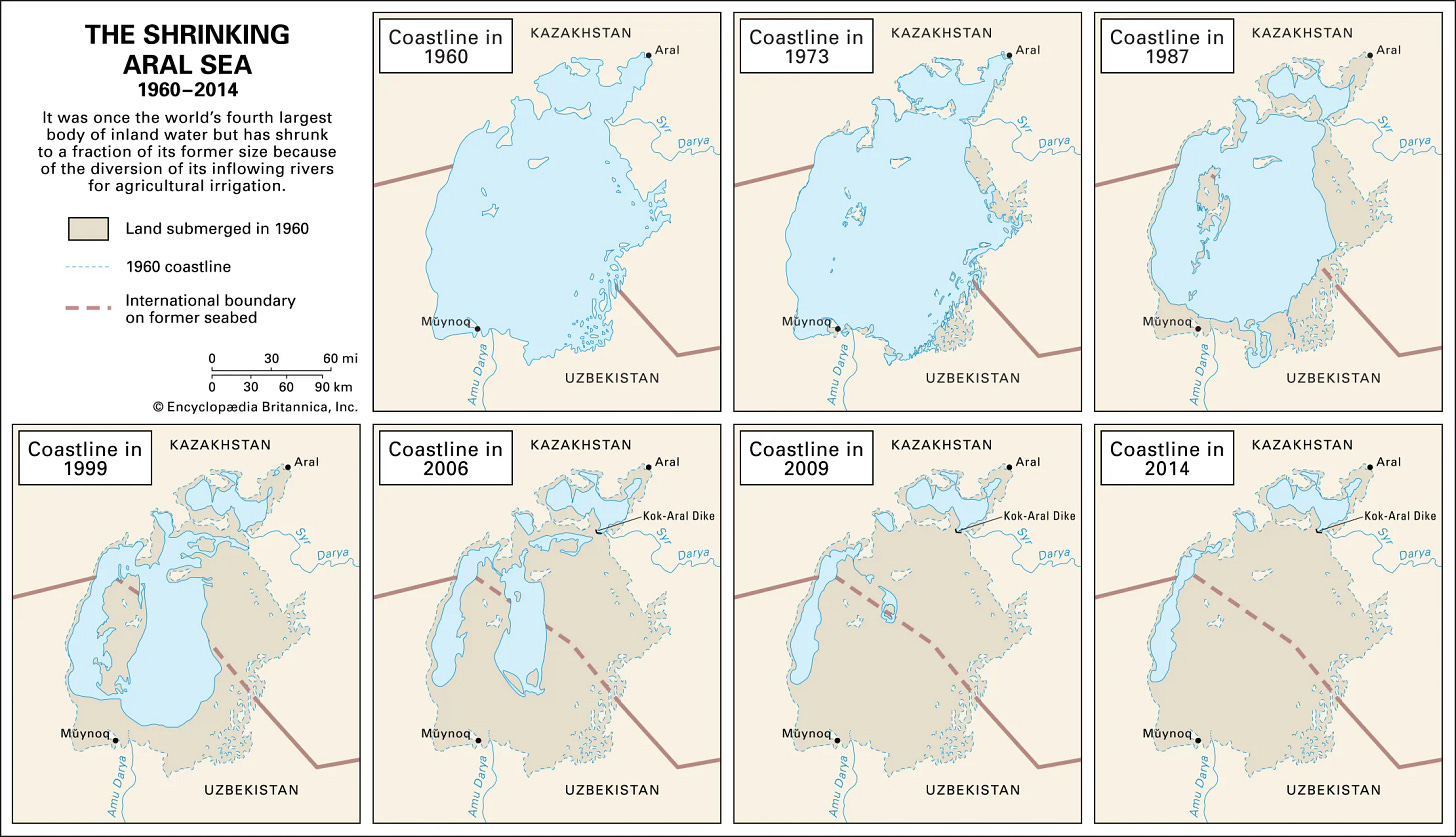

The Aral Sea is in Central Asia, and geographically sits basically 50% in Kazakhstan, 50% in Uzbekistan, or at least historically it did. Beginning through a series of decisions to use and divert the waters of the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya rivers, for things like irrigation and industry and the development of cities within the region, the flow of the two rivers that fed into the Aral Sea began to significantly diminish. By the early part of this century, the sea itself had reduced to about 10% of its original size by volume.

What we have today is largely considered one of the major ecological crises here on planet Earth. And this one is especially human induced because we overused the water as it flows into this region. It's been an ongoing issue. It's been well studied. It's well documented. Most history books of the region, most geography books, even in university settings in the United States for geography courses, you can learn about this as an environmental issue.

The government of Kazakhstan came to USAID with the request that we try to help in whatever capacity we could within this region. And so we have worked with a team of scientists and specialists who know about this region to come up with an idea and a plan to be able to bring something forward from the American people to help. We developed the Environmental Restoration of the Aral Sea project.

The ERAS project.

Yes, exactly. We are only given a certain amount of funding from Congress that's allocated to our programming. We also have a certain amount of time, our activities tend to work on a five year time scale. So we only had so much time and so much money to be able to implement something that would have be able to have a tangible impact within this region. What we decided on was an environmental restoration idea to help with the resilience of the northern Aral Sea zone. (When we say the northern Aral Sea zone, that generally means the Kazakhstan side of the Aral Sea, as opposed to the southern part, which would generally have been in Uzbekistan).

We would create what we call an oasis using black saxaul trees. They're really a desert shrub, grow very small, they have to live in a desert ecology. They're native to Central Asia, which is another reason that we chose them as a way to help within this area. This was a way that we could begin to help sand stay in place, because sandstorms and dust storms are an increasing challenge in Central Asia that has direct impacts to people's health. There's a lot of dust and particulate matter in the air. Because of all of the years of using the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers for irrigation, there's a lot of use of fertilizers and chemical enhancers for the agriculture industry, a lot of which ended up in the Aral Sea area. And so you actually have a lot of chemicals that are on the surface. They can also be blown around in the air, which again has a negative impact for the health of the communities in the region. So this is what we kind of approach with this. [Dr. Adkin emailed me later that the ERAS “Oasis” site is located at 45°49'16.9"N 60°32'03.0"E].

The other benefit of using the saxaul trees is that it can kind of be an initial starter to the ecological restoration of this area. You plant these as an initial first tree. That can allow other plants to begin to exist in this region, which will then hopefully bring back other plant species, birds and animals to help it become a true ecosystem within this area once again.

So that's kind of an intro and I can dig in deeper and deeper as you have questions about specific aspects of the work as well.

Where are you standing currently in the efforts? I’ve read that you have dug 300 furrows and planted about 200,000 black saxaul seedlings? And you’re expanding your work into Uzbekistan with ERAS II?

Yep, that's right. Everything you said so far is correct. We've planted 200-ish thousand saxaul trees. We will do a little bit more planting in these upcoming spring months. This will be our final round. Basically, we'll go back through our area and confirm which plants did not survive, and we'll do a little bit more planting to replace some of the plants that didn't make it. That was planned into our work to try to do a little bit more tree planting to make sure we have as many successful-growth trees as possible.

It's slightly different in Uzbekistan because the sea there is based in the Karakalpakstan region of the country, it’s semi-autonomous, has a lot of different rules. We are going to try to do some tree planting over there. We're also going to try to do some kind of work on climate smart agriculture. Again, these are based on requests from the government of Uzbekistan.

A really big component is really the bilateral work between the countries. USAID is a convening power, right? We try to set the stage, work with the two governments, bring them together and have a dialogue about what's needed in this region. The Aral Sea disaster affects all of Central Asia. We bring delegations back and forth. We brought technical specialists from the government of Kazakhstan and universities of Kazakhstan and then of Uzbekistan. We basically did a cross match. We took them from Uzbekistan, brought them here to Kazakhstan so they could see firsthand what are the conditions and the challenges here. And then we did the reverse, taking a delegation from Kazakhstan to Uzbekistan so they could similarly see what the challenges are and have that dialogue about what's going on. We also had a very large conference this past May in Kyzylorda, Kazakhstan, where we brought together just over 100 people for a conference on Aral Sea issues.

Can you tell me about the geopolitical context of your work? Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan both recently had transfers of power, from Nursultan Nazarbayev to Kassym-Jomart Tokayev in Kazakhstan and Islam Karimov to Shavkat Mirziyoyev in Uzbekistan. From what I’ve read, there’s a sense that both of those new rulers are trying to be at least somewhat less “dictator-y” than their predecessors: Tokayev has initiated some quasi-democratic constitutional reforms, Mirziyoyev is working on some reforms as well. Central Asia is transitioning from being mostly made up of walled-off dictatorships to sort of trying to engage more with the international community. President Biden is engaging with the Central Asia Five Plus One initiative. Can you talk more about that?

I'm definitely not a political analyst. That would be a State Department function. But you did bring up the C5 Plus One platform. President Biden was able to meet with all five presidents of Central Asia at the United Nations General Assembly back in September. That was a way that we are trying to engage in the dialogue with all the countries. USAID has been here in Central Asia for 30 years. As a part of the U.S. government, we've been engaging with the countries for a very, very long time.

Just from the environmental side, there are changes here in Kazakhstan. President Tokayev, in his September speech to the nation, announced the new Kazakhstan Ministry of Water. So there is an interest on environmental issues and environmental topics. And even from the C5+1 when President Biden met with all five presidents from Central Asia, one aspect of it, the statement that came out of that meeting, that statement very specifically mentions the transboundary water issues of Central Asia, and specifically mentions our USAID work.

You mentioned the dust issues and obviously there's been many seriously damaged towns like Moynaq and Aralsk that used to be, you know, ocean towns and now aren't. There are iconic pictures of the boats in the middle of the desert. The Aral Sea disaster hit the local communities really hard. This is a really desolate region.

How do people on the ground feel about the Aral Sea restoration efforts, about USAID's involvement? Is there a sense of renewed hope, or sort of cynicism and thinking it won't pan out to anything?

The Aral Sea was a very large hub for fishing and that pretty much entirely has collapsed. Even most of the fish that exist in the northern Aral Sea now were fish that were reintroduced into the Aral Sea and then used for fishing purposes. Even then, sometimes the government has had to put temporary pauses on fishing or certain measurements on fish, you can't get fish under a certain size for example, to be able to make sure that the stock of fish remains.

There are certain industries that were certainly impacted. The fishery industry was massively hit by this. So if you go to a town like Aralsk which used to be a port town, you can still see the crane infrastructure there that they would have been able to hoist goods off of very significant ships and then bring it into the town and distribute it throughout the region. And so all that infrastructure still remains. There's been generally a shift to other occupation. So now there's an increase in animal husbandry. Lots of herders out there. So you have sheep, goats, camels, etc, within the region. That is something that people are still able to do for an income.

The population has diminished. Some towns effectively don't really exist anymore. We visit towns when we go out there to see the direct impact. For example, one town has moved several times now. As sand dunes shift with the winds, it more or less consumes the town and it is no longer habitable for the people to be there. So there's one town that I think now has maybe about 10 to 20 residents left because the town has been consumed by the sand dunes. And it just doesn't make sense to keep moving, moving, moving. It's going to be a perpetual issue.

Other towns have also had interventions from other donor organizations, you know, it's not just USAID that's out there, there's been other donors as well. And so what they've done is basically planted green walls, also using saxaul trees to hold back sand dunes from encroaching. And those have been quite successful. So you can go to some of these towns, you can see the planting of the trees and how much sand is being held back. And so this is a way that they're trying to be able to maintain the communities that still exist within this region. You also have other people who are coming out there who there are some plants that you can grow out in the region. There is a limited amount of farming and agriculture that still exists out there.

So I'd say overall, it's been largely just an adaptation to the climate as it changed with the diminishing water. The Dust Storms are an increasing challenge within this region which will probably necessitate further changes for some of these communities. The number of dust storms in a given year has been increasing.

And again, I'm also not a health expert, but what we've seen and we've heard from colleagues is that, you know, incidence of asthma and respiratory issues is increasing in the region. But medical information is just not very robust. They're very small towns. They don't have advanced medical facilities in every single town to be able to measure and quantify what's going there. So sometimes some of this could be anecdotal, passing of information orally from community to community as well. But still, it's something that we're taking seriously because we know it is a threat to these different communities.

Speaking of medical issues, I've read that there were Soviet bioweapon experiments in what were formerly islands in the Aral Sea, but now of course are not. What is the legacy toxin issue like? Is that a major factor in your work? Are you concerned about the biosecurity aspects or some of the toxic heavy metals, some of the other stuff left behind by Soviet industry and weapons development in that area?

Well, for context, the Kokaral Dam is a dam managed in conjunction with the World Bank and the government of Kazakhstan that holds back most of the waters of the North Aral Sea. It's a military controlled environment to be able to maintain security and maintain the levels of water within the region. So access to all these sites is not…you know, you can't just go into some places. You have to have permissions to be able to access them.

We do know about it. We haven't done a full toxicology of all the soil out there to know if our exact site has any remnants of, you know, this testing that occurred out there. We did it more for levels of natural sediments out there, especially salt, to know if the soil itself is too salty for plants to grow. Because there are some areas of the Aral Sea zone where we can't do afforestation work because the soil is just simply too salty to really accept new life and new plants.

Beyond that, I don't know the full history of everything that went down out there.

Are you seeing any kind of a broader ecosystem redevelopment, like wildlife moving to those oases or migratory birds stopping by? What sort of conditions are you seeing at the oases now that you've been working there for a couple of years?

So saxaul trees themselves, when we plant them actually, they're only a few inches high, even at two years old. And when we walk away, when our USAID work finishes, again, they're only going to be slightly bigger than that. They're a desert plant. It takes a long time for them to grow. And in those initial years, they're basically dropping a really, really deep root system to be able to tap into any available moisture within the region. So for them to gain any substantial height, say maybe two meters, they could actually be 10 years into their life cycle. It's a long, slow grow process for them. We can show you some images to see what's going on, but again, our site is quite new, and so most of the plants are still quite small. I mean, the largest ones that we have, the most successful growth rates that we have, may only at this point be about two feet tall.

Plus, you have to space them out. It's a desert system, so the level of water that you would need for them to grow has to be spaced out. We go to other sites that had been maybe planted 10 or 20 years ago to see how they have been growing and what heights they're achieving. Those are definitely two or three meters high. And there's even saxaul tree nurseries that exist in Aralsk. Because they've been planted on a specific site and they're cared for, those are actually five or six meters tall. They're quite substantial in size. But again, they've been maintained by humans, watering them and taking care of them day in and day out so they can grow a lot.

The other part is that our entire planting site is currently fenced. Our plot is quite huge. It's a one kilometer by two kilometer area. and the entire area is currently fenced in. Because this is a scientific understanding of how these trees can grow, we wanted to fence it in to take away some of the other variables, like grazing animals, because as I mentioned earlier, there's animal husbandry.

There's also native animals that do exist out there. One is a Kulan. It's a wild jackass. And so that also could be eating our plants. So we wanted to try to limit those external factors to see what methodology is actually successful for our plant growing. The hope is that once we know that the plants have been successful, we can remove the fencing and then allow the ecosystem to take its natural course.

Excellent, fascinating. So that nicely leads into my next question, which is, what are your near, mid, and long term future projections for this? At what point do you think you can remove the fencing? At what point do you think you can expand to plant more fenced areas? And, this may be a decades or even centuries question, at what point do you think you can start reclaiming substantial land and water area of the Aral Sea as a functioning ecosystem? Long term, how much of the Aral Sea do you think there's a chance that we could get back?

So for USAID's part of this, things could change, but at least right now, the work that we have through our Environmental Restoration of the Aral Sea activity will conclude in 2025. Basically a year from now. This upcoming spring, when we go out to the Aral Sea this upcoming April, that is when we will initiate the handover process to the government of Kazakhstan. So the site that USAID developed and funded, we will begin handing over full ownership of that site to the government of Kazakhstan, and then they will take it from there through their various departments.

We've been working with the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea, which has been a very primary partner for us. They have their offices out in Kyzylorda, Kazakhstan. They're a regional entity with all countries being party to this group. They will also be a very prominent factor in this work here in the Aral Sea, and they will likely, it'll be up to the government of Kazakhstan to make this decision, but they would be the ones likely to help lead on the continued efforts out there.

Beyond just the trees that are out there, which is a part of it, one thing that was based on the request from the government of Kazakhstan is we also dug a well. There is groundwater accessible, and so we contracted out and brought in a company to bore the well into the earth to be able to access the water. The reason for this is we're also trying to develop a small nursery on site. Currently, all the trees are grown in Aralsk and some other smaller areas within the region, and then they have to be brought the whole way into this zone, which is quite a long process to do. The hope is that we'll build a small nursery here on this site and that they'll be able to use the water facilities from the well that we've dug to start turning what we've initially started into a new site, that they can continue to just radiate and expand and expand and expand.

You'd have to speak with the World Bank for their specifics, but the World Bank is also in talks with the Government of Kazakhstan to do a significantly larger afforestation project. They’re sort of waiting for the results of our project. They want to know what is the best way to plant these trees and to care for them to achieve the greatest success of the trees. That way, when they begin planting a much larger forest ecosystem using the saxaul trees, they can have a greater success rate of the trees to help the situation out there to a greater degree.

Again, we'll hand over to the government of Kazakhstan. The plan currently is that a small nursery will be built there to help facilitate all of this. Then they'll begin working with other entities and other donors for additional afforestation projects within the region.

The current work that we're doing, the intended goal is not really to bring back the water of the Aral Sea. We're trying to work on the current situation that exists in the area where we're planting. Even if water levels did rise, this would not be an area that would essentially become immediately inundated with water.

It's not a target of this current activity to somehow increase the overall water levels. Even in our separate larger activity, which is our WAVE activity or Water and Vulnerable Environment activity, we do not specifically have a main goal to increase the waters of the Aral Sea.

One of the things that we have to understand is that the two major rivers that feed into the Aral Sea, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya rivers, are the primary water resources for all of Central Asia. And while we're trying to increase the overall water efficiency of the use of these waters throughout the entire region, we have to also be realistic that if upstream we increase the efficiency of water use, that may just allow more water to flow downstream that could potentially be used by an additional farmer. And that water could actually be used to grow crops and maybe still not continue to flow down and reach to the Aral Sea. We have to look at the much broader regional picture of regional water use here in Central Asia to think about what could happen for the Aral Sea.

There's many bodies of water like this in the world. Even here in Central Asia, there's similar situations occurring at Lake Balkhash in Kazakhstan, as well as the Caspian Sea, which is also seeing rapid decreasing of water levels there as well. These are just from the region, but again, this is happening in many places around the world.

I'll note that the World Bank, again, also in their work streams, there are discussions of…there's this dam that I spoke about earlier. It's an earthen dam that holds back the waters of the northern Aral Sea. There are some general discussions of raising the level of the dam, which would then hold back more water within this northern part. And that would specifically be in Kazakhstan, not in Uzbekistan. So those are some of the ways which we would actually see more water retained within the region, but that's not a direct work of USAID.

Thank you very much.

So, is there any lingering Cold War or Soviet nostalgia feeling around this? Or do people say, “thank god the Americans are here to clean up the Soviet’s mess?” I mean, this is a a major environmental catastrophe that occurred under the aegis of a rival superpower and now, in a small way, Americans from the Soviet’s historical rival are arriving to help.

Sure. People understand that a lot of the infrastructure was developed during the Soviet times here in Central Asia. That was part of the agriculture, that was part of the damming of the rivers for hydropower, which also had an impact on the water use here in the region. But then they also are fully cognizant that they continue to benefit from all that infrastructure into the post-Soviet era.

So as the countries have, you know, as they gained their independence and control of all these different pieces of infrastructure, they still obviously continued to use the majority of it for the development of the economy. It just kind of persisted, it continued into the history of these countries.

There is an organization where the five countries come together to discuss water rights and water allocations. They meet every six months of every year and they have for decades. They look at the water resources available in Central Asia, and they then discuss in a closed door meeting with their ministries and ministers about the water allocations in Central Asia. So this isn't something that, you know, the United States just came in and started doing. We've been trying to assist those things that have already been ongoing. So, for example, with this group working on their regional water dialogue that they have about water allocation, our lead for that went to the meeting and presented on the water modeling work that we're doing. It's a very extensive water modeling of the ecosystems of Central Asia on the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya rivers, from the glaciers the whole way to the Aral Sea. Every bit of water and infrastructure that we can understand that feeds into the water system in Central Asia, we're trying to put it all into a model. And then we share this with the governments and we train the governments on how to use this modeling for more effective decision making for water use in Central Asia.

So we're just trying to kind of be a continuous part of this dialogue, bring more data to it, help bring everybody to the table to have this conversation. We also have leveraged what we call our Regional Coordination Committee meetings, which we also have every six months, we try to align with them, have a preparatory discussion of using the water resources in Central Asia. So for us, our next one will be this upcoming April. And then that aligns with, their higher dialogue on water use in that we bring together academics, the technical staff from all five of the Central Asia governments, from the different ministries and every single government. The ministries are different, but we generally try to get a representative of the Ministry of Water, Environment, Education, Energy, and their Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Agriculture. So all of these representatives coming together, usually 40 to 60 people, to inform this ongoing dialogue for everything here in the region.

It wasn't the U.S. government coming in and revolutionizing the entire sector. They already had here in Central Asia really great mechanisms for dealing with these issues and dialogue between all the different countries. Again, we just tried to leverage and enhance those different aspects as much as we can, based on our conversations with the five Central Asian governments as well. With USAID, we meet with their ministries and ask them, what do you need of us? How can we help you? How can we assist? Do you need more data? Do you need more information? Do you need more meetings? What is it that would help you within this dialogue in this situation here in Central Asia? That hopefully makes sense.

It does. Thank you. Back to one of my other questions. What sort of key information would you like the American and the global public to know about the Aral Sea and your work in the Aral Sea? What is something that you would love to tell people on the street that you think they really should know, that few people know?

Sure. First of all, I think it's really working on the resilience of the landscape and the communities out there. We're trying to have a positive direct impact on the communities that exist in the Aral Sea zone. I mean, within the the broader Aral Sea zone, it's about 40 million people. So there's a significant number of people in Central Asia that could be negatively impacted by sandstorms and other socioeconomic changes within the region that we're really trying to help with.

Part of this is this innovative approach that we're bringing to the oasis within the region. And it's also part of it is that we're trying to bring a lot of innovation here, new methods, new technologies, new best practices that have been learned from other parts of the world. Lots of information sharing that we can try to bring together to this region, trying to make those connections so that they can learn. So that when our work as USAID concludes, they can maintain and continue all of this work into the future as well.

And it's also about ownership for the governments and the local people, that they can take control, that they can, you know, own this issue and own this idea and take it to the next level, whether that's through direct on-the-ground work, or if that's maybe even in-house inter-region research. It's a great way that we can kind of co-create potential solutions and restore this area as much as we possibly can.

I think it's a really great effort that we can work with all of them so directly and facilitate all this, the cooperation within the region.

Well, thank you so much. One more question. What is your field season like? At what times of the year are people on site in the desert?

Sure. So we did build a field station at our site. It's small, but it is there because we had to have a safe place for anybody to be because in the winter, it usually goes down to about negative 30. In the summer, it'll go up to upper 40s into the 50s, Celsius, as well. So we had to have a safe place where they could be protected from the wind and the cold. And then also sandstorms, because we have recorded sandstorms at our site as well.

It has a kitchen dining area, a bathroom facility, and then another area for sleeping. Up to 14 people can sleep at the site. And then there's a kind of more open area that can be used as an educational facility. So we have actually already hosted the German Kazakh University. They have a master's degree program in integrated water resources management. They took their students out there and we opened up our site for them to be able to use and learn about what we're doing out there, but also as an educational facility for them to use at this area. So there is that site out there for everybody to use.

Generally, we go out there in the spring and the autumn. I mean, you can access it in the summer and in the winter, but the conditions tend to be very extreme. Because in its exposed desert in the summertime, the heat of the sand itself can burn your skin. So it's really hard to be out there. And the heat is just sweltering and overwhelming.

So we tend to go out there generally from March to late May, and for the autumn, September, October tend to be the best times to go out there. But we have other people out there. I spoke about this nursery. There's people out there currently who are assessing the situation for the construction of a nursery on site. You can make it out there, it’s just that during the snowstorms and things like that, ou can lose sight of the road and during dust storms, you can lose sight of the area. So it's just about a safety measure overall.

This is extraordinary. Now, a more open-ended question.

What does it feel like?

Like, what is the emotional experience of going out to this area that used to be a sea and realizing the magnitude and the scope of what's happened and beginnings of the potential of restoring it? What does that feel like?

Yeah, it's really amazing. It really is. And it's really hard to comprehend. So at our, first of all, you usually end up going to Aralsk and staying there overnight before you go further and further out into the desert. And there's generally one hotel there that we all stay at and you walk down the street to the port.

So it's amazing to stand there and see these huge, you know, hundred foot tall cranes on the coastline, but knowing that the water is today very far away, that this infrastructure has just been sitting there and that it once had an amazing purpose for this economy and for the communities within the region that doesn't really exist in that way anymore.

But then when you really go out into the Aral Sea, it becomes amazing just to see. Because the whole place is just covered in seashells, just trillions of seashells all over the ground. And so you're walking around, and it's this weird cognitive dissonance of seeing seashells all over the place, but also standing in the middle of the desert and thinking that within a lifetime, people would have seen water here.

We’ve interviewed people and they say that, you know, they were some of the last people who probably ever swam in the Aral Sea as we historically knew it. As, you know, a full-sized body of water. And these people are alive, we're working with them! They're the scientists who are working with us to do this work. So it's kind of amazing to think how drastically this landscape has changed within one lifetime.

And the other part is also in the place where we're planting our trees. It's a little hard because we don't have super precise measurements for that exact location. But somewhere around 30 meters of water would have been overhead of us at that site.

Now we're standing on what would be the sea floor and the water level would have been 30 meters above our head. And just to try to comprehend that is….your brain can't fully wrap your mind around standing in this amazingly huge area. You're bumping across the desert in a car for hours on end, and everything that we would have been driving on would have been the sea, and it no longer exists. So it really is, it's a phenomenal way to learn about humanity and decision making. Sometimes poor decision making and poor management of resources can really have consequences.

But then on the flip side of it, there's so much work now going to try to correct some of the problems that were made. We know what issues exist, we know the impact it's having on the environment, the animals and the communities, and how we can try to make positive change for all those different things. And so that's also just really great to see. When we were out there last time, we had maybe 30 or 40 people that we took out there in a huge entourage of people. Everybody planted one tree. That was part of our day there. We provided an opportunity. Everybody was given a tree and we planted it in our little oasis. And everybody said that was amazing feeling to be a part of a solution to the issues within this region. It was just one tree, but it was a part of a broader idea that they were all being a positive impact. And so a lot of people really took that away as, you know, a sense of happiness and pride.

I didn't even mention, another little part that we've done is a small grant with Aral Tenizi, a group in the town of Aralsk. This was part of our WAVE activity where we do small grants. She's actually removing trash and fishing nets out of the Aral Sea [northern remnant] to try to remove pollution that's in the current waters to make it a healthier ecosystem. So she bought a little dredger boat thing that has a hook where she can kind of pull things out of the water. And anything that's plastic she uses a melting machine, but doesn't burn anything so there's no emissions from it. She melts down the plastic and then she turns them into the little paving tiles that people can use for their gardens and things like that.

I mean, this is just one example through USAID of a person in the community who saw an issue, thought of a way to fix it and address it, applied for a grant and received it, and now is having a positive impact for her community. And so there's lots of little positive things that are happening out there, and it's really great.

That is just amazing. Wow. Well, thank you. Thank you so much. Absolutely fascinating.

Thank you.

This one of my favorite W A's ever. What a huge area of desert beauty! What great work the USAID folks are doing in the face of enormous challenges of scale.. I would love to live in that beautiful area both as an austere windswept plain or as a sparkling sea.

Can you do a follow up issue where you interview people involved in our own great drying up inland sea- the Great Salt Lake? It s a world ecological disaster in its own right.

I

I'd be curious to hear an update on this, given the recent changes at USAID. Will the work go under under some other department?