Book Review: Abundance by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson

A roadmap towards a brighter future for America.

If you’re interested in left-leaning U.S. politics, or the U.S. environmental movement, or the U.S. efforts to fight climate change, you’ve probably already heard about Abundance, by renowned NYT writer Ezra Klein and newly minted Substacker

. In policy-nerd circles, it’s the book of the moment, dominating discourse at every level from Substack comment sections to Congressional caucuses. So what’s it about?One alternative title for Abundance could have been “Lessons Learned from the Biden Administration.” Why didn’t effectively unlimited federal money for cleantech lead to a China-level mega-ultra-super-duper surge in cleantech deployment, instead of just the biggest-in-American-history-but-still-not-quite-enough surge in cleantech deployment that we actually got? And clean energy was a relative success, with many other efforts stalled far more disappointingly. For example, why did massive amounts of federal money for rural broadband lead to very little broadband being built before Biden’s term was up? This isn’t just a technocratic question, it’s a vital political one — maybe if we’d had more concrete, successful completed projects to point to, we could have staved off the victory of an outright authoritarian presidential candidate in 2024.

The answer is that “lack of money” wasn’t the major factor holding back clean energy (and much else) in America. “Red tape” was a much bigger issue, and not so much the traditional idea of “red tape” in the sense of “federal or state bureaucracies being slow to work” as much as a particularly American form of “bottom-up red tape,” in which a rich and litigious society combined with uniquely hijack-able state and federal permitting processes adds up to “every single aspect of every clean energy project can be paused by lawsuits from fossil fuel advocates (and/or crazy people) that cause expensive and interminable delays.”

This is why we haven’t built nearly enough clean energy as we should have. Similar process-and-litigation-delay issues at overlapping and different scales are also why we don’t have any decent large-scale public transit and why we have such a terrible homelessness crisis. That’s a bold thesis, but Abundance makes a very strong data-driven argument to support it.

You could subdivide the themes of “Abundance” in a lot of different ways. Its five chapter titles are “Grow,” “Build,” “Govern,” “Invent,” and “Deploy.” The major public goods it focuses on needing to build more of are “housing,” “clean energy” and “public transport.” The major institutions it discusses include the U.S. federal government, state governments, local governments, NGOs and civil society, and academia. In this review, I’m categorizing my takeaways into sections defined by three cross-cutting aspects that stood out to me: “anti-environment effects of environmental review (primarily but not entirely federal and state),” “limits to housing (primarily but not entirely local/municipal)” and “ossification of science funding (primarily federal).” All of these are linked by a core theme of state capacity – which focuses not on building a bigger or smaller government, but a more functional government, a government that can achieve its goals faster and get more results per dollar spent.

“Liberals speak as if they believe in government and then pass policy after policy hamstringing what government can actually do…

The big government-small government divide is often more a matter of sentiment than substance.

Neither side focuses on what scholars call “state capacity”: the ability of the state to achieve its goals.

Sometimes that requires more government.

Sometimes it requires less government.”

— Abundance

U.S. Environmental Review Laws Are Now Severely Harming The Environment

Most of the environmental protection laws passed in America during the environmental revolution of the 1960s and 1970s have been as close as any law gets to absolute 100% resounding successes. The Clean Air Act and its amendments, the Clean Water Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Superfund Act – these laws and many more like them at the state level have cleaned up America’s air, water, and soil on a historic scale, saving millions of people from premature deaths. Emissions of almost every air pollutant except greenhouse gases (which are colorless, invisible, and economically much harder to build a coalition against) has declined sharply in recent decades.

Once omnipresent smog has eased. Rivers across America, like the iconic Cuyahoga in Ohio, have gone from “so polluted they’re catching on fire” to “full of paddleboarders and sturgeon.” This writer’s parents spoke about how if you leaned against an outdoor wall in Pittsburgh in the 1980s your back would end up covered in coal dust, and when they’ve gone back to Pittsburgh in the 2020s they remark on how incredibly clean it is now.

This is all good! These are very good things! Attempts to weaken vital Clean Air Act protections, like the “license to pollute” now being attempted by the Trump Administration, are bad and should be stopped.

But a specific subset of environmental laws, those instituting “environmental review” processes, have become, after years of accumulated legal cruft, a grave danger to the environment. They are hobbling America’s ability to fight climate change while ratcheting up the cost of living for the American people. The two “poster children” for the counterproductive effects of environmental review are CEQA, a state law, asnd NEPA, a federal law.

Reagan signed the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) into law as governor, and Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) into law as president. Both were originally intended to be minor procedural tweaks compared to the epoch-making pollution limits in the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act: NEPA was intended to mandate something like “a dozen-page report on possible environmental harm has to be compiled for each building project.” For NEPA, that meant “each project funded in part by federal dollars,” and for CEQA, a 1972 state supreme court decision ruled that it meant “every project that the state regulates” — meaning all building projects.

But anti-development activists — primarily a lot of well-meaning environmental groups — seized on the NEPA and CEQA review provisions as a strategic opportunity, a crack that could be wedged open, a now-omnipresent legal and procedural weak point to stop any project anywhere. It’s really easy to file a lawsuit saying “The NEPA review was not satisfactory, didn’t consider XYZ potential environmental harms of the project, you need go back and do it again.” And a lot of courts will generally rule in favor of that position, because who could object to a simple demand from the voice of the people to be extra-super-careful that your building project isn’t hurting something important? And precedent is cumulative – if everyone else is doing longer environmental reviews, you’re at risk of looking sloppy if you do a short one.

So now NEPA and CEQA reviews take years and run to thousands of pages — and multiple different reviews are often required for different stages of the same project. Between 2010 and 2018, the average time to complete a NEPA environmental impact statement (which isn’t required for all projects, but very often is for major infrastructure projects, especially with public funding or on public land) was four and a half years! That’s a delay before you can start building. We can’t build a clean energy future anywhere near as fast as we need to with that kind of lag time.

I completely understand how this happened, and how a lot of good people worked hard to make it happen with the honest intention of making the world a better place. I suspect that if I was a twenty-something in the 1970s as opposed to the 2020s, I would absolutely have been one of the people doing this! I would be super excited about using NEPA and CEQA to block development! I would be reading and writing about the terrible pollution of the era and its nightmarish health consequences and accelerating biodiversity loss and what appeared at the time to be a serious human overpopulation danger (but turned out fine). I would say things like “Finally, the people have a voice to stop the destructive march of Moloch, devourer of nature!” Maybe I’d even be into those obscure ultra-nerdy warnings that carbon dioxide emissions might be doing something bad to the Earth’s climate.

But the world of the 2020s is very different from the world of the 1970s. The “polarity has reversed” on the moral and ecological impact of U.S. environmental review processes and anti-development litigation.

For much of the fossil fuel-powered twentieth century, if you cared about wildlife and wild places and ecosystems and ecology and the entire beautiful n-dimensional kaleidoscopic tapestry of Earth’s biosphere, holding a default position of stopping any new building project, or at least wanting to have the option to relatively easily slow or stop any building project by suing for more review, made a lot of sense — leading to the longstanding, always-questionable, but now completely and woefully outdated political trope of “jobs versus the environment.”

But in the 2020s, the biggest environmental threat facing the planet is climate change. Thanks to amazing technological innovations, most of the new stuff being built, in the U.S. and worldwide, is now cleaner than the old stuff it’s replacing — solar farms and grid-scale batteries instead of coal plants, EVs instead of gas cars, new houses with heat pumps instead of fuel oil furnaces.

In addition to reducing climate change-causing greenhouse gas emissions, the new generation of clean “electro-tech” will massively reduce humanity’s mining footprint, with the entire mineral-recycling global battery industry likely requiring less earth moved total than sustaining our existing fossil-fuel burning infrastructures requires per year. And with the emerging Battery Mineral Loop, that could be a one-time dig!

To fight climate change and preserve Earth’s biodiversity, we need to build as much of this new clean stuff as we can, as fast as possible, to speed up the replacement of the oil, dirty, carbon-belching stuff. One of the more important world-defining facts of 2020s Earth is that humans building new stuff is now, almost all the time, a net pro-environment activity by default.

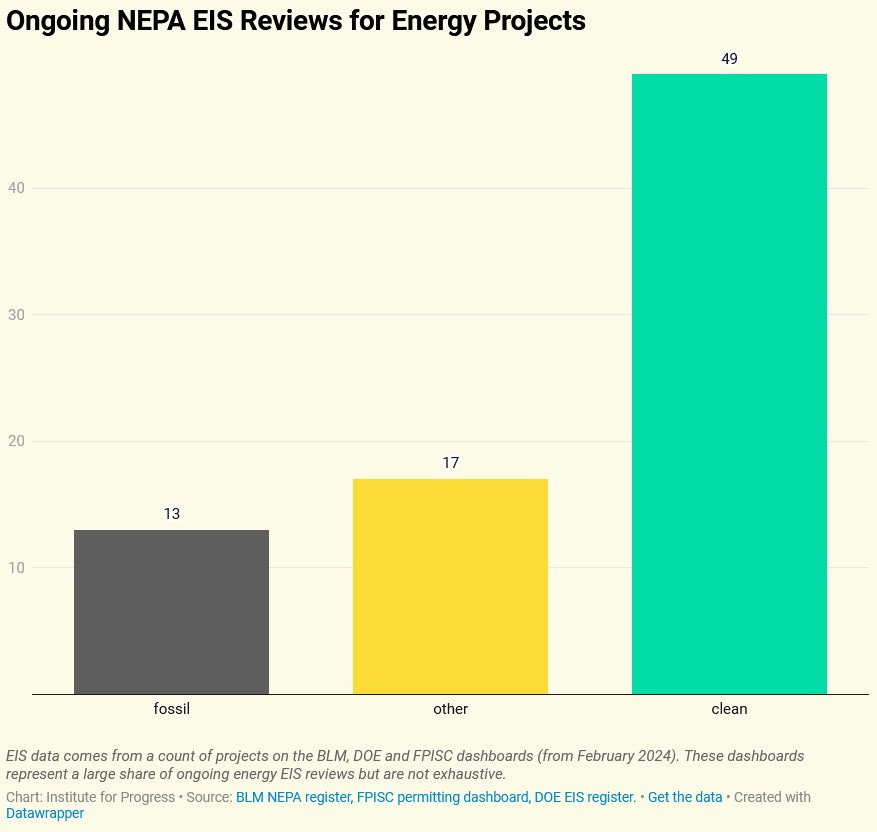

And that means that NEPA reviews, and everything else making it harder to build new stuff are now disproportionately harming clean energy projects.

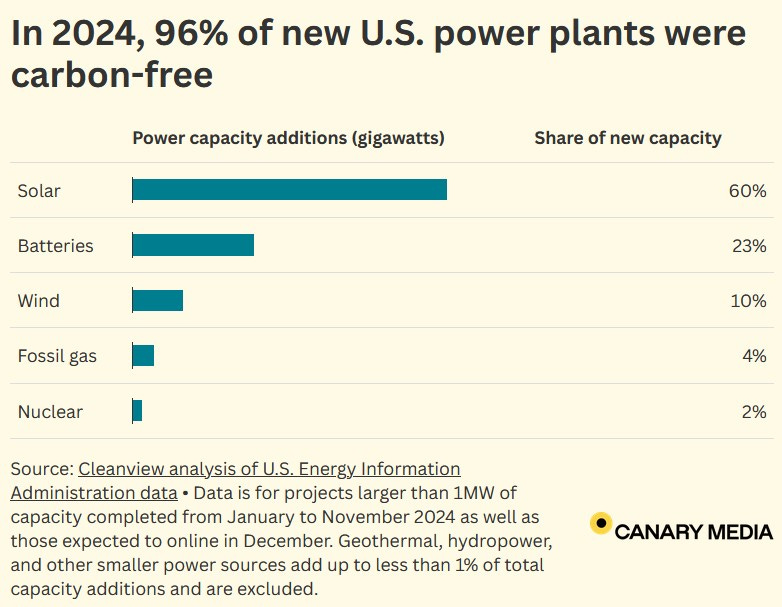

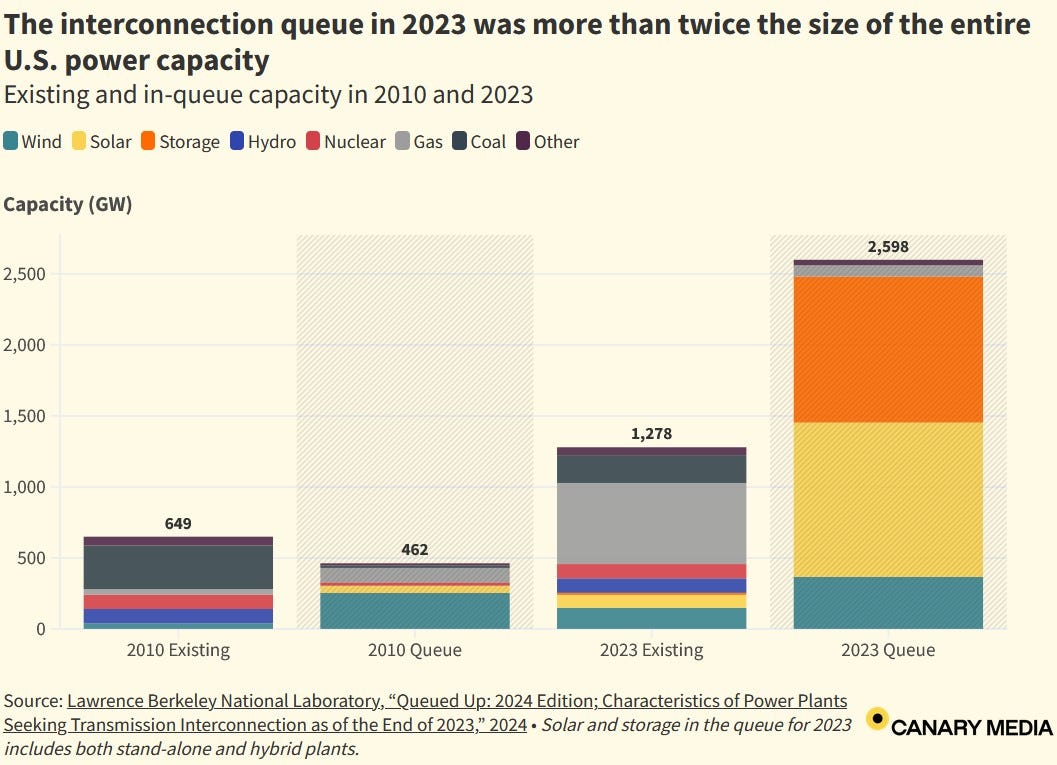

The effects of these permitting barriers have added up very fast — especially when they block key bottleneck-overcoming projects like power transmission lines, which can allow lots of clean energy projects in one region to power cities in another. With the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022, the Biden Administration unleashed unprecedented federal support for clean energy — but permitting and review barriers remained. By 2023, the “interconnection queue,” the line for proposed projects that someone already wanted to build to get a chance to plug in to the national grid, had grown to over 2.5 terawatts (aka 2,500 gigawatts or 2,500,000 megawatts) — much bigger than the total existing U.S. power supply of around 1.3 terawatts.

That’s a truly extraordinary situation: by 2023 (and since then), America had far more already-proposed solar and battery capacity waiting to be built than all of America’s existing electricity-generating capacity from all sources already built! If we’d just built everything that companies and developers and co-ops across the nation had already applied to build in 2023, the entire nation would be running on clean electricity by now — and we’d have tons more left over to electrify heating, transport, data centers, and more.

The proposed Manchin-Barrasso bipartisan permitting reform bill of 2024 would have exempted most energy projects, both fossil fuel and renewable, from environmental review, but it didn’t pass — in large part due to furious opposition from much of the the environmental movement on the grounds that this would make it easier to build some fossil fuel projects, despite the fact that it would also make it much easier to build overwhelmingly more renewables projects and hyper-accelerate the entire country’s electrification! This was a truly massive strategic error, a historic own-goal screw-up that this writer strongly argued against at the time. We didn’t do permitting reform, and now the best climate action legislation in American history is on track to be repealed when it’s only achieved a fraction of its true potential.

The key point is this: red tape used to be good for the environment, but red tape is now bad for the environment.

Way too much of the legacy environmental movement hasn’t caught up with that yet, and unfortunately that means that a lot of environmental groups have become, on net, bad for the environment. Not just by holding up permitting reform at the federal level, but by adding to the permitting drag at the state and local levels, holding up many much-needed clean energy, housing, and public transit projects over relatively minor issues in a way that prolongs the fossil-fueled status quo and makes global warming worse. In the worst cases, well-meaning but woefully misguided environmentalists’ anti-renewable development efforts can be indistinguishable from fossil fuel-funded astroturf campaigns to choke off cleaner competition.

As people from Bill McKibben to Kamala Harris to the Abundance authors have called for, we now need to reverse the polarity of the environmental movement itself to keep up – and become a pro-building, pro-development, “YIMBY” (Yes In Our Backyards) movement. Because that’s what we need to build enough clean energy in a fast enough time-frame to stop climate change.

That’s a big part of what I’m trying to do with my writing. But beyond the macro-level picture, the details of specific projects are worth examining to see what this looks like in practice, and Abundance delivers a multitude of in-depth data-driven case studies.

One particularly infamous case is California high-speed rail – or rather the lack thereof. The combined impact of CEQA and NEPA is why1 California still has no high-speed rail despite the state and federal government repeatedly trying to fund this much-needed emissions-reducing, economy-boosting and life-improving clean public transport infrastructure.

“In 2009, then, this was the status of high-speed rail in California: It was a signature project of the president of the United States. A signature project of the most powerful governor California had had in decades. Voters in California had set aside billions to make it real. And the federal government was adding billions more. It is hard to imagine a more favorable climate for the project. A spokesman for the California High-Speed Rail Authority joined a call-in radio show and told listeners that they’d be able to “ride that train from San Francisco to LA in the year 2020.”

But progress crawled and costs ballooned…

The scaled-down plan was estimated at $22 billion…

The latest estimate is it will cost $35 billion to complete and it won’t begin carrying passengers until sometimes between 2030 and 2033. If all goes well. …

These days, six years is roughly the amount of time it takes California to realize that its bullet train needs to be pushed back by another decade. In the time California has spent failing to complete its 500-mile high-speed rail system, China has built more than 23,000 miles of high-speed rail…

Trains are cleaner than cars, but high-speed rail has had to clear every inch of its route through environmental review, with lawsuits lurking around every corner. The environmental review process began in 2012, and by 2024 it still wasn’t finished.”

— Abundance

The problem isn’t governmental inefficiency or lack of money or labor issues. It’s not just China that’s way better at trains: highly regulated and unionized countries across Europe are able to build widespread high-speed rail networks for a fraction of the price and in a fraction of the time of America’s fumbling efforts. It’s the litigation and environmental review process – the permitting slog, the red tape, the endless time and money-draining lawsuits and delays, the infinity of “veto points” where some person or group with enough funding to sue (and there are a lot of those in America) can threaten more lawsuits and demand more review before anything gets built.

“A new layer of government: democracy by lawsuit…

Decisions that are often made by bureaucracies in other countries are made by judges in our country…

America has twice as many lawyers per capita as Germany and four times as many as France. Much of this energy is devoted to suing the government...

The problem we faced in the 1970s was that we were building too much and too heedlessly. The problem we face in the 2020s is that we are building too little and we are too often paralyzed by process.”

— Abundance

In addition to crippling our transition to greener energy and infrastructure, that same “democracy by lawsuit” paradigm is also what created America’s dire homelessness crisis. And the mechanism by which it did so was simple: it made it way too hard to build homes.

Why So Many Homeless People? Not Enough Homes.

This sounds too simple to be true, like a five-year-old’s idea of why homelessness exists. Surely there’s deeper issues going on here? Maybe poverty, substance abuse, mental illness, unemployment, inequality, lack of a social safety net, “bowling alone” atomized individualism, or whatever else you’re concerned about already?

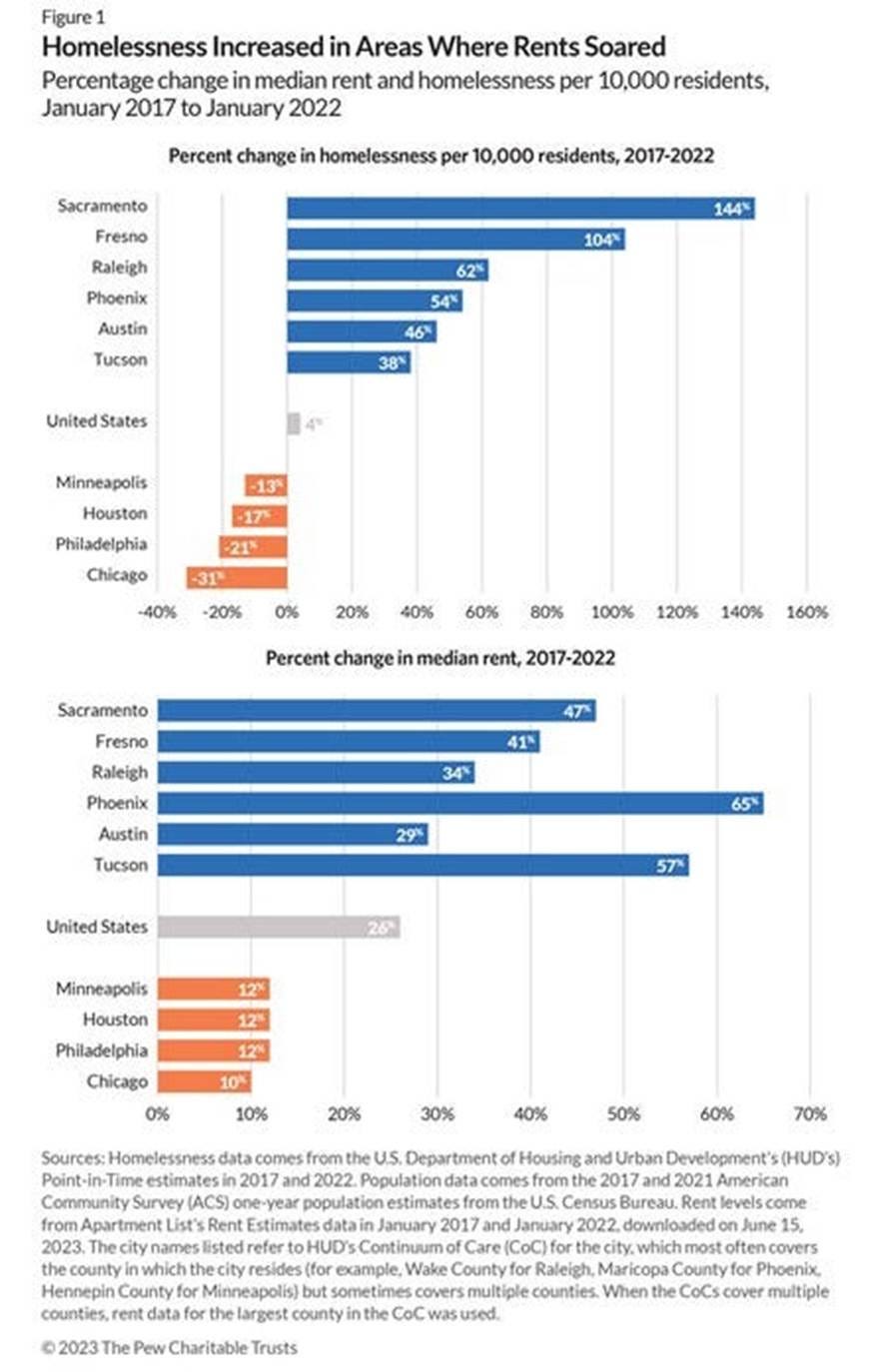

Nope, not really. Those things are real problems, but they don’t actually correlate with homelessness at all, while “availability of homes” very strongly does. If there’s enough affordable houses to go around, even horrible life problems generally don’t cause homelessness. California has far more homeless people *per capita* (adjusting for population!) than West Virginia, which has way worse rates of poverty, drug abuse, and just about every other social malady you’d care to name. If housing is cheap, you can probably still have a home even if your life is really screwed up. If not, a personal problem can easily turn into missing rent and then being kicked out onto the streets.

“Imagine a game of musical chairs.

With ten chairs and ten people, everyone will find a chair when the music stops. That will be true even if one of the players is on crutches.

With nine chairs, someone will inevitably be left out. That’s when individual life circumstances begin to predict homelessness.

If you live in a city with too few homes, poverty and drug abuse and unemployment and mental illness make it likelier that you will be among those who end up without a home.

But the cause of homeless isn’t the poverty or the addiction or the unemployment.

All of those conditions are far more prevalent in, say, West Virginia than in California, and yet California has six times the per capita homelessness of West Virginia.”

— Abundance

This is driven in part by environmental review laws as well, but mostly by a much denser thicket of restrictive zoning regulations often imposed at the municipal or even neighborhood level. Those restrictions tend to get voted for by existing residents due to to a pernicious logic of economic self-interest: if houses are scarce, the people already owning homes are sitting on an asset that’s appreciating faster and faster. It’s a collective action wicked problem in which far too many Americans feel that the only way to make their family richer is to make some other family poorer. This often gets portrayed as primarily about “preserving neighborhood character” or some form of hyperlocal environmentalism, but “make other families poorer” is what it amounts to in practice.

Minimum parking lot space requirements, maximum residency limits, banning accessory dwelling units, minimum number of staircase requirements, architectural or historic “compliance with the character of the neighborhood” requirements, minimum square foot per inhabitant requirements, every-room-has-to-have-its-own-kitchen-and-shower requirements, and especially the scourge of “single-family zoning” that forces suburban sprawl and prevents European-style low-rise multi-family apartments – it all adds up to make any housing development other than luxury condos unaffordably difficult to build.

There are a lot of factors pushing people to campaign for such requirements, even beyond homeowners’ economic self-interest. Well-intentioned people campaign against building ugly, cheap and crappy housing (and/or not-so-well-intentioned people campaign to keep poorer or nonwhite families far away from their house), but their campaign makes things much worse because ugly, cheap and crappy housing being available is a heck of a lot better for *everyone*, very much including the people living there, than no housing being available at all.

Tenements are better than tent cities. Boarding houses are better than bridge underpasses.

This writer personally has in the recent past2 lived for over a month each in several extremely cheap and crappy short-term rental apartments, like “poop rises up through the shower drain when you flush the toilet” or “ceiling fan breaks during a heatwave and there’s no AC” cheap and crappy (and those were two different apartments!), and can confirm that they were still very, very glad to be living there as opposed to on the street!

Restrictions on housing may sound like a boring, local-only issue, but they’ve added up to become a massive problem for American democracy on a number of levels. Homelessness is a classic club to bludgeon anti-authoritarian blue-state politicians with. Red states tend to have less zoning restrictions and are building more homes to attract more residents, which is why Texas is steadily gaining electoral votes and California is losing electoral votes, making it harder for a Democrat to win the presidency with every national census. And perhaps worst of all, it shifts the entire national dialogue into a scarcity mindset. When you artificially limit housing supply, you drive people towards a narrower, more selfish, more grasping politics, born of genuine desperation. You end up with psychotically evil political outcomes — much of the Republican Party now pitches “deport innocent people who have lived in the U.S. since childhood!” as a solution to high housing prices.

The Abundance writers don’t go this fair – the whole tone of their book is polite and data-driven almost to a fault – but this writer would like to translate the moral weight of this data into practical consequences for the extreme circumstances of 2025. I think it’s now fair to say that if you’re an American homeowner and you’re trying to stop any apartment building being built anywhere in America – yes, even on that nice bit of green space next to your bucolic suburban house – you are actively enabling the Republicans’ authoritarian agenda. This kind of “NIMBY” (Not In My Backyard) -ism is helping create the soil in which authoritarianism grows, the cultural and economic conditions of artificially imposed scarcity that make people vote for atrocious mass deportations and mistreatment of homeless people.

Science Needs To Fund More Weird Risks

Zooming in on another key aspect of human civilization, he “Invent” chapter of Abundance focuses on internal funding processes in science and the federal agencies which (used to) fund it in the United States. The authors find that a lot of the problems there “rhyme” with the problems in clean infrastructure build-outs: too much paperwork, proceduralism, and a risk-averse “stick to the rules” mindset are slowing progress. America’s most brilliant minds are spending much of them time doing mind-numbingly tedious paperwork before they can get any grant funding, and the grant funding that does get awarded is playing it too safe and not investing in the kind of radical ideas that might lead to the biggest new breakthroughs. Basically, Klein and Thompson’s science funding thesis can be summed up as “more research dollars need to be flowing to people like Katalin Karikó3.” When you get into the details, that’s an extremely convincing argument.

Katalin Karikó grew up in a house with no running water, daughter of a potato-farming family in rural Hungary. She trained as a scientist and migrated to the United States, where she ended up working at the University of Pennsylvania and developed an unusual interest in something nobody else was working on: the potential medical applications of messenger ribonucleic acid, the molecule that cells use to ferry information from DNA in the nucleus to protein-making ribosomes. As early as the 1990s, she started submitting dozens of grant applications requesting funds to work on this weird research idea to the National Institutes of Health, the major U.S. medical science funding body. Almost one application per month for two years. All were rejected. She teamed up with another scientist, immunologist Drew Weissman, and they diverted some funding from other grants to keep doing this research while applying for more grants together. They still got rejected. They eventually got a proof-of-concept early success published in a minor journal in 2005. It didn’t attract any new funding. Dr. Karikó was demoted at the university, didn’t get tenure, and was eventually, in her own words, “kicked out” of academia in 2013. America’s science institutions had judged her a failure.

But did she give up? She did not.

Leaving academia wasn’t the end of the story. Two startups, one husband-and-wife affair in Germany called BioNTech and one U.S. team called “Moderna” which hired Dr. Karikó in 2013, pursued this weird “mRNA” research in the private sector, backed by philanthropies like the Gates Foundation.

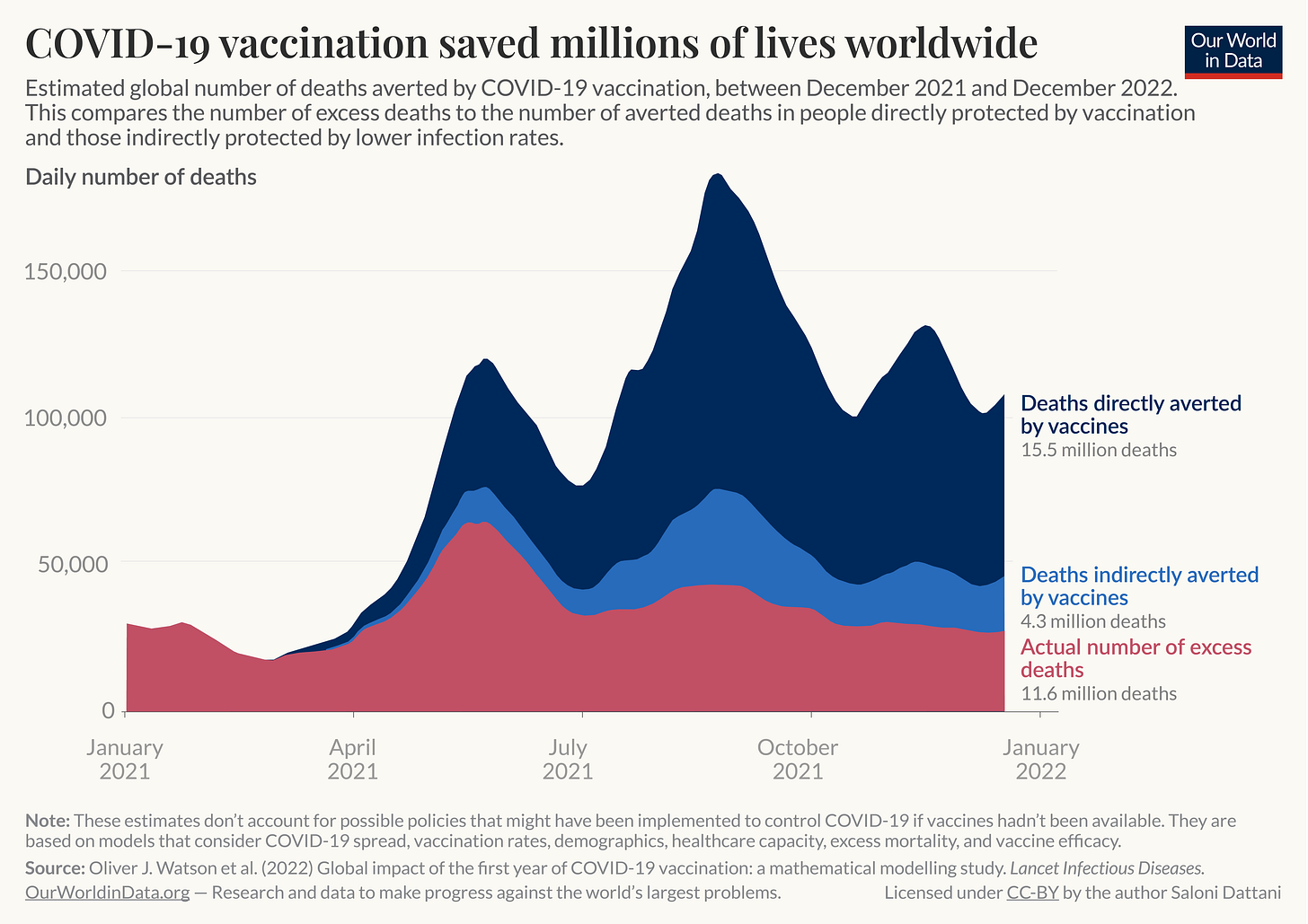

You probably know by now what came next. During the COVID pandemic, mRNA technology directly based on Dr. Karikó’s research led to the fastest vaccine deployment in history. Moderna had their mRNA vaccine recipe ready within forty-eight hours of Chinese researchers publishing the genetic code of the COVID-19 virus in January 2020, and by December 2020, it started rolling out to the public after months of clinical trials – a rapid deployment helped by an unusual “make it happen fast and ignore the paperwork” government program known as “Operation Warp Speed.” Billions of mRNA vaccines have now been shipped, saving millions of lives, and scientists are now talking about using this technology to create vaccines against heart disease and some forms of cancer – the two biggest causes of death in the United States.

In 2023, Karikó and Weissman won the Nobel Prize. For a technology arising from a research project that they tried hard to start in the 1990s, only got to scale up by 2020, and that the U.S. government repeatedly rejected opportunities to fund. Karikó is quoted in Abundance as saying “Even now, I am working on therapies that were part of grant applications that were rejected twenty years ago.”

We barely got a COVID vaccine at all, and the only reason we got it was because one offbeat scientist who’d been rejected over and over didn’t give up on her weird bright idea.

This is not an isolated case. Consider the history of paradigm-shifting breakthroughs in science. Manhattan Project or CERN/Higgs Boson-type breakthroughs, where there’s a clear agreed-upon objective and a big team and dedicated facilities and lots of funding, dominate popular perceptions of scientific advancement, and they can be incredibly valuable, but they’re more of the exception than the rule. Abundance goes in-depth on several examples of weird, offbeat science winning through to world-changing success, and this writer can think of many, many more. As recent history shows4, incredibly weird-sounding research into lizard spit and moldy cantaloupes and Italian soil samples can turn out to be some of the most effective, highest-return investments that a government can possibly fund!

Science progresses when smart weirdoes get the chance to try crazy things. We are right on the cusp of a new age of incredible scientific and technological progress, and if the U.S. wants to lead on that (maybe restarting in earnest in 2029) it needs to fund more risky, out-there, weird-sounding research projects. A lot of those projects will fail, but the ones that succeed will make it worth it a thousand times over.

“Inventions that may seem outlandish today may soon feel essential to our lives.

Streets filled with electric self-driving cars that give us mobility without emissions and free us from the vast number of deaths caused by faulty human reflexes or judgment.

Gigantic desalination facilities that transform our oceans into drinkable tap water.

An economy with robots that build our houses and machines that take on our most dangerous and soul-draining work.

Wearable devices to scan our bodies for diseases.

Vaccines that we can rub on our skin rather than inject at the tip of a needle.

As unrealistic, or even ludicrous, as some of these ideas might seem, they are not much more ludicrous than a rejected, ignored, and unfunded mRNA theory that came out of nowhere to save millions of lives in a pandemic.

To make these things possible and useful in our lifetime requires a political movement that takes invention more seriously.”

—Abundance

There’s already an impressive burgeoning movement trying to figure out practical ways of reforming science funding away from tedious paperwork and towards transformative progress. Random online science enthusiasts with access to funding, like Tyler Cowen’s Emergent Ventures or Scott Alexander’s ACX Grants, have been issuing zero-paperwork no-strings-attached instant grants to promising young scientists with weird ideas, and the results so far are highly promising. The MacArthur Genius Grant is another great model with more established institutional backing, and what they do is similar: identify extremely smart and driven people who really want to do more research, then give them money with no bureaucratic overhead. As Akshat Rathi chronicled in Climate Capitalism, China in the early 2000s shoveled money at long-shot EV and battery research back when that seemed like a very risky bet. They now lead the world in fast-spreading ever-cheaper battery technologies and earned 10% of their GDP from cleantech last year! The U.S. needs to embrace a more high-risk high-reward mindset for science funding and deployment, using the story of the COVID vaccine and Operation Warp Speed as an example, to make us once again the kind of country that invents the future.

“In the 1940s, the Office of Scientific and Research Development mapped out the chemistry and production challenges for penicillin and turned an obstacle course into a glide path.

In 2020, the US government similarly identified the bottlenecks to rapid vaccine development and removed them.

In both cases, the government served as a chief national problem solver, molding its policies to fit the moment.

It is a vision of a new kind of entrepreneurial state.

It is the government as a bottleneck detective.”

— Abundance.

We need to get one heck of a lot better at deploying our new inventions – it’s no use having an amazing new scientific breakthrough if you can’t build it in the real world. In an archetypal example, which Abundance discusses at length, the U.S. historically funded breakthrough solar panel and lithium battery research, nailing the “invention” side, but squandered its lead and let China become the first to build solar and batteries at sufficient scale to make them the world’s cheapest energy source. This dovetails back into the review/litigation issues that most of Abundance discusses, and makes it a fundamental cross-cutting question of values, not just specific legislative or administrative details. People need to be thinking in terms of outcomes, not of process. Of achieving great things to advance human well-being, not making sure that all the paperwork is right. Paperwork, litigation, and procedure can be useful, especially in preventing genuine abuses of power, but the U.S. has erred way too far in the too-hard-to-build direction. And that reduced people’s quality of life, made people justifiably angry, and left our political scene wide open to what’s beginning to look like the worst abuses of governmental power the nation has ever seen.

Trumpism Is Degrowth, Scarcity, and Hate. Abundance Is The Way Forward for Freedom and Liberal Democracy.

People of all political persuasions are deeply frustrated that America has become a “build-nothing country.” They see and feel it in the absurd incongruities that our low-state-capacity government-by-lawsuit society has created, where pocket supercomputers are cheaply available for the masses but owning a roof over your head feels more and more like an unattainable luxury. Many of them are so frustrated that they’re willing to embrace crazily counterproductive and harmful ideas like “let a drug-addled billionaire randomly fire government workers” in the hope that that does something good. It’s not a coincidence that Trump made his name as a real estate developer – as sleazy and worker-abusing as that career was, it linked his name to the idea of stuff getting built in the physical world. Americans are hungry to build again, and angry that it’s not happening.

Now, the time is ripe for liberal America to channel that energy to become the party of building as well as the party of freedom. The current Republican Party feeds off the anger at existing scarcities (as well as a multitude of cultural resentments and a lot of other issues) but does less than nothing to make them better, instead harnessing it to fulfil their own agendas. The Trump Administration is a presidency of degrowth and scarcity. Their policies are indistinguishable from what you would pursue if you wanted to make housing, energy, and transport as expensive as possible. Tariffs on basic home-building supplies like Canadian timber, deporting construction workers, tariffs on steel, tariffs on car parts, tariffs on battery parts, cuts to tax credits incentivizing battery factories, cuts to tax credits incentivizing clean energy projects adding new layers of red tape to clean energy projects, outright denial of permits to clean energy projects – what we’re getting right now is an Abundance Agenda in reverse5. A Scarcity Agenda – all the better to make people angry and try to use their dominating position in the information environment to direct that rising anger, that sense of “not enough for everyone, someone’s got to go,” into cruelty towards immigrants, the poor, and the dispossessed. That’s how you get ICE secret police on the streets.

There is no lack of horror for the Democrats to campaign against — unaccountable masked men abducting people who have never committed a crime, omnipresent self-serving corruption and sleaze, the atrocity that is the destruction of America’s scientific and health infrastructure, an ever-increasing cost of living actively made worse by government policies, cartoonishly-villainous freakishness like Alligator Alcatraz, the other horrible evil things that have happened between my writing these words and your reading them. A cascade of cruelty and coercion and crime.

The Abundance Agenda is something to campaign for. And even if the 2026 and 2028 elections are more about “against” than “for,” if firmly opposing all the horror is the best campaign-season messaging, Abundance is a set of tools to build a long-term better political order and more successful nation from the foundation of a short-term election victory. Something to deliver the results that Americans demand, something to materially lower the cost of living, something to make sure that the next period of Democratic governance – if we fight hard enough to defeat wannabe-autocracy and actually get one! – doesn’t end in disappointment and reaction like the last one just did. In the meantime, it’s something blue states can do to overcome their massive problems of housing scarcity, homelessness, and skyrocketing costs of living, which in addition to their immediate human costs provide an easy fund of attack lines for the pro-authoritarian party to use in efforts to entrench their rule. And although the book Abundance almost exclusively focuses on American politics and institutions, its lessons can provide inspiration for other countries with saner governments (especially countries in the Anglosphere with similar political cultures and English common law-based legal systems, like Canada, Australia, and the UK) to enact pro-abundance reforms before their politics reach American-style crisis points.

“What we are proposing is less a set of policy solutions than a new set of questions around which our politics should revolve.

What is scarce that should be abundant?

What is difficult to build that should be easy?

What inventions do we need that we do not yet have?”

— Abundance

The very good news is that there’s a heck of a lot of “low-hanging fruit” on the table to get things working better. It’s not that difficult technologically to build vast amounts of stuff very fast (look at China), and the U.S. has the money to make it happen – the barriers are political, procedural, and legal. And we’re starting to mobilize political action to take down those barriers.

So far, federal-level attempts to do that haven’t worked out great. A 1996 law exempted border security projects from environmental review (to the eventual glee of the horrific Trump administration) and President Biden signed a 2024 law that exempted semiconductor factories from environmental review (this one might yet pan out OK!). As I’ve written before, the failure of the 2024 bipartisan permitting compromise was a gigantic missed opportunity6.

But America is a federal republic, and there have been some amazing successes for the dawning Abundance Agenda in state and local jurisdictions. In recent years, the YIMBY movement has gone from strength to strength in state and local American politics, culminating just a few days before this article was written in an absolutely revolutionary state-level legislative victory in California that exempts almost all apartment buildings (as well as food banks, health clinics, clean water and broadband projects, and more!) from CEQA review. Governor Gavin Newsom even name-checked Ezra Klein and the Abundance Agenda when signing it into law.

It’s too soon to see how the California YIMBY victories will turn out (though I’m excited!) one other state-level case provides an undeniable example of just how much potential progress is available if we adopt Abundance-inspired policies to make it easier to build stuff.

When the vital I-95 highway bridge in Philadelphia collapsed due to a steel-melting flaming tanker truck crash on June 11, 2023, following the normal state procurement and review process for a highway repair project would have taken an estimated “twelve to twenty-four months” to fix the bridge – an unacceptable delay that would disable a key transit link for the entire Northeast. So Democratic Governor of Pennsylvania Josh Shapiro issued an unprecedented emergency declaration that essentially said “skip all the normal procurement steps, ignore all the paperwork, do zero environmental review, do whatever you need to do to get this fixed very fast.” The state picked two construction companies with good records (and 100% union labor!) that happened to already be working on projects physically nearby and told them to get going right now. Repair work began within hours as soon as the fire department left, and continued around the clock in shifts covering all twenty-four hours of the day. In addition to skipping the mountains of paperwork involved in normal review processes, the emergency declaration empowered the construction workers to take risks that would normally be illegal as long as they sped things up: a street sign in the way was knocked over instead of unscrewed and taken apart, and paving began while it was raining. The risks worked out. The bridge was fixed in twelve days.

Twelve months down to twelve days. Not by compromising on labor rights, but just by the government untying the bonds it had made to limit its own action.

Imagine if we did this for a solar farm. Imagine if we did this for every solar farm – and wind farms, and grid-scale batteries, and power transmission lines. The economic fundamentals were there for a clean energy boom much bigger than the one we got: once the IRA supercharged the funding picture, there was active developer interest to build terawatts of new clean energy capacity, enough to power all of America twice over, and it was reviews and lawsuits and delays that stopped that from happening. If we’d combined full-on permitting reform with Operation Warp Speed-style emergency-level government focus and relentless elimination of bottlenecks, we might have achieved 100% clean electricity for America in the window between the Inflation Reduction Act funding of August 2022 and the election of November 2024, and now be ramping up to build even more to power mass electrification of transport and heating, with rising data center demand barely a blip compared to this epochal surge of constantly arriving clean electrons. Imagine what the 2024 election might have looked like if Biden and Harris could have said, credibly, “We have rebuilt the nation’s entire energy system. We have ended deadly air pollution from coal plants. Our emissions have plummeted. Millions of new green jobs have been created. Your electricity prices have gone down because of the huge amount of new power-generating capacity we brought online. We are leading the world to solve climate change and safeguard our children’s future.”

That’s what we have to make happen. It’s time for American liberalism to build again.

“We seek a politics of abundance that delivers real marvels in the real world. We want more homes and more energy, more cures and more construction…

Abundance contains within it a bigness that benefits the American project.

It is the promise of not just more, but more of what matters.

It is a commitment to the endless work of institutional renewal.

It is a recognition that technology is at the heart of progress and always has been. It is a determination to align our collective genius with the needs of both the planet and each other.

Abundance is liberalism, yes.

But more than that, it is a liberalism that builds.”

— Abundance

It’s also why SNCF, a renowned French rail-building company, quit the California rail project and instead built an entire nationwide rail network in Morocco (which I rode!), where - as they said - the political system was more stable.

Don’t feel bad for me because of this, it was my choice to live there and I’d do it again - I’m from a not-at-all-impoverished middle-class background, but I really like traveling and learning what life is like in other countries, and I’m unusually willing to undergo substantial discomfort to be able to afford to do so.

Which most definitely includes accepting more people like Karikó into the U.S. in the first place: the current artificial cap on H-1B skilled worker visas might have prevented Karikó from ever coming to America if it had been around in the 1990s, and the current hyper-xenophobic administration is horrifically damaging the historic U.S. strength of being an attractive destination for scientists from around the world. It’s not a major focus of the book, but Abundance definitely includes immigration as an archetypal pro-abundance policy — and building housing is key to sustaining political support for immigration and escaping xenophobic doom spirals.

Isaac Newton developed optics in part due to experiments such as sticking a blunt needle into his own eye socket, and discovered gravity by asking seemingly pointless questions about obvious stuff like “things fall down”. Charles Darwin discovered evolution by closely examining finches’ beaks. John Snow developed modern epidemiology when he stopped a London cholera outbreak by illegally removing the handle from the Broad Street well pump. Henrietta Leavitt developed the first way to measure the distance between galaxies by analyzing the brightness of Cepheid variable stars on photographic plates – despite working only as a low-paid “computer” and not being allowed to use a telescope as a woman in the 1910s. Marie Curie discovered radioactivity by messing around with weird glowing powders that eventually killed her. Albert Einstein discovered relativity by thinking really hard about what it would be like to ride a beam of light. Mary Hunt made mass production of penicillin possible by analyzing the “pretty golden mold” on a random cantaloupe she found at a market. Barry Marshall discovered that H. pylori bacteria caused peptic ulcers and stomach cancer, and when nobody believed that bacteria could colonize the stomach he proved it by drinking a petri dish the bacteria and making himself sick. Jane Goodall discovered non-human tool use by going into the woods and sitting next to chimpanzees for a really long time. Doxorubicin, a core precursor of modern chemotherapy drugs, was discovered by analyzing bacteria from a soil sample taken in the garden of an Italian castle. Beata Halassy injected research-grade viruses into her own breast cancer tumor and discovered a new successful cancer therapy. Tim Friede intentionally let himself get bitten by venomous snakes hundreds of times so that his blood could be used to develop what is potentially a universal antivenom. GLP-1 agonists, the molecules behind the incredible obesity-curing products now transforming global public health, were discovered by intense analysis of the strange properties of the saliva of the Gila monster. (Yes, lizard spit got us Ozempic!)

Does any of that sound like something that could easily pass a federal grant review and win funding in today’s risk-averse hyper-scrutinized political climate, especially if nobody had ever done it before? Can you imagine what Republicans would be saying about projects like this on social media? Your taxpayer dollars at work…on THIS?!

In a weird way, I think that long-term, the U.S. might be in some respects perversely lucky that an out-and-out “degrowth” presidency is happening due to Republican nativism, not Democratic environmentalism. If some of the more extreme voices in the climate activism space had won power, the economic aspects of Trump II closely resemble what degrowth environmentalism might look like in practice – massive cost increases in housing, transportation, and energy, but (in this hypothetical) due to government action to combat the real-world threat of carbon pollution, not the imaginary threat of “foreign-ness.” I fervently hope and desperately believe that the madness of a rightist-degrowth presidency is setting us up for a massive swing back towards liberalism and against hatred and xenophobia – and I strongly suspect that a hypothetical leftist-degrowth presidency would set up a massive swing back towards conservatism and against anything even remotely tied to climate action or environmentalism. Although it is hard to imagine offhand how bad that would be compared to what’s happening right now, I suspect that if the left alienated the public enough with active degrowth policies, the U.S. right would find some way to make it even worse.

Also, in 2025, the Trump Administration has made noises about limiting NEPA review with executive action, but in the context of their constant attacks on clean energy and economic competitiveness more broadly, it’s clearly meant to be another effort to prop up the dying fossil fuels industry. Cutting paperwork isn’t a silver bullet, it’s more like a “last hurdle blocking you from crossing the finish line” if you’re already trying to run the race — it doesn’t do nearly as much good when the president is simultaneously cutting tax credits for cleantech, arbitrarily denying federal permits for clean energy projects subsidizing fossil fuels, and tariffing construction materials! Defeating this nightmarish administration is Priority One — Abundance is a plan for how to make sure nothing like it happens again.

Right on Sam Matey - excellent book review with so many pros and cons regarding the realistic atmosphere of why America tackling the climate crisis, our housing shortage, and how China can outrun America on building high speed rail points a big arrow to the bottlenecks which could explain the voters being so frustrated that so many didn't see the treachery and betrayal by Trump and his GOP before voting for him. Our future is now in quicksand exposed to the silent violence caused by Trump.

Our legacy media fell short reporting on the rebuilding of I-95 in PA back in June of 2023, but you mentioned the successful, ahead-of-schedule project that both Biden and Shapiro played key roles in the emergency response and rebuilding of the I-95 bridge. I remembered that the administration also worked with state and local partners to provide resources to those affected by the Philadelphia bridge collapse, including assisting small businesses and impacted workers - do you agree that our MSM could support America better in actively supporting the good news and the truthful bad news better with Americans? Thank you for your articles in your 'Weekly Anthropocene' journalism in Substack.

I liked the audiobook 'Abundance' too.

Well done!

Add wildfire to the long list of damages that NEPA and CEQA are doing.

Will return and restack tomorrow.