Wild Parrots in Cities Are A Delightful Development

In the Anthropocene, urban green spaces are increasingly safe havens for flocks of these colorful, intelligent birds. Awesome!

London. Paris. Hong Kong. Singapore. Chicago. New York City. Los Angeles. San Francisco. Sydney. Rome. Athens. Phoenix. Dallas. Brussels. Houston. New Orleans. Barcelona.

What do these cities have in common? In the Anthropocene, they’ve all become home to at least one species of wild-living parrots, generally the descendants of escaped or abandoned pet birds. Social, colorful, melodious, and intelligent, the arrival of parrots in modern civilization’s great cities is a delight—and may well end up saving a few species! Let’s explore this phenomenon.

London, Paris, Rome, Miami, Tokyo…

The Anthropocene city parrot par excellence is surely the rose-ringed parakeet (Psittacula krameri), a wide-ranging generalist native to India and Africa, but introduced everywhere from Japan to the UK to the USA. In Tokyo, spreading flocks of rose-ringed parakeets hang out near the Tokyo Institute of Technology. They’re particularly common across Northern Europe, where this writer has seen their cacophonous flocks enlivening several different cities’ parks1 (including on my recent trip to Amsterdam). In Paris, they split the air with their cries from the leafy Bois de Vincennes on the outskirts of the city to the half-restored Notre Dame Cathedral near the center. In London, they swoop through St. James’ Park. In Rome, they soar over Vatican City and perch on the Colosseum.

Brussels, the de facto capital of the European Union, is estimated to be home to around 10,000 rose-ringed parakeets as of 2023, possibly the descendants of a few dozen released from a small zoo in the 1970s. Researchers note that rose-ringed parakeets benefit from both warming temperatures caused by global warming and abundant food in restaurant, market, and park-filled urban neighborhoods.

New York, Chicago, Houston, Austin, New Orleans….

Monk parakeets (Myiopsitta monachus), originally from South America, now are well established across the USA, particularly known for breeding across the greater New York City and Chicago metro areas. In fact, they’re now found in a whopping 43 U.S. states! They survive Chicago’s harsh winters by switching “almost exclusively” to backyard bird feeders as a food source from December through February. Monk parakeets were reportedly some of the first animals to return to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and are now widespread in the Big Easy. They’re common across Texas, with colonies in Houston, San Antonio, Austin, and Dallas. They’re also increasingly common in European cities as well, sharing space with the rose-ringed parakeet from Rome to Brussels to Barcelona.

And wherever they go, they start winning over some friends and admirers. At least one person is leading parrot safaris in Brooklyn. The Economist notes that monk parakeets building their elaborate stick nests around warm electrical equipment has caused more than a few power outages in Long Island in recent years, but that they remain popular with residents nonetheless, and that local utility company PSEG has stuck to a policy of not destroying nests during nesting season. Former Chicago mayor Harold Washington called them a “good luck talisman,” and Chicago residents once threatened a lawsuit to successfully block the USDA’s proposed removal of the local monk parakeets. This underscores a key reason for the success of parrots in Anthropocene cities-they’re cute. They’re fun, colorful, and people like having them around.

And there’s a certain poignant historical resonance to the arrival and flourishing of a small green big-nest-building parakeet in eastern North America. For we once had a native species answering this description: the Carolina parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis), which ranged from the Atlantic to the Great Plains before mass deforestation and unregulated hunting contributed to its extinction in the 20th century. The last known specimen, or “endling,” named Incas, died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918. The monk parakeets are now living in much of their old habitat, possibly occupying some of the same niche and potentially playing a similar role in local ecosystems.

America drove the Carolina parakeet to extinction, but we’re now providing a welcoming home for their distant cousins. To this writer, that’s worth celebrating!

Hong Kong

The yellow-crested cockatoo (Cacatua sulphurea) is native to forested islands of East Timor and eastern Indonesia2, where it’s become critically endangered due to logging and mass trapping for the pet trade. Interestingly, one of the species’ most well-protected and stable populations is now outside of their native range, consisting of the descendants of pet yellow-crested cockatoos released into the parks of Hong Kong.

The Hong Kong cockatoo population has grown from around 50 in the 1970s to around 200 now, and it’s stayed around that level for several years, possibly limited by a lack of appropriate nest sites. (They’re not builders like monk parakeets). With an estimated 2,000 mature individuals or less remaining in the wild, Hong Kong is home to at least 10% of the global population of this species! And it looks like there might be a similar feral population developing in Singapore, although it’s much less well-reported and is probably considerably smaller, for now at least.

San Francisco

San Francisco is home to several parrot species, but perhaps the most well-known are its cherry-headed conures (Psittacara erythrogenysi) aka the red-masked parakeet, originally from South America.

The SF conure population won fame as “The Parrots of Telegraph Hill” in a book of the same name. (The Weekly Anthropocene has read it, it’s really good!) As of 2023, there were an estimated 220 individuals, and they’re increasingly beloved by local residents, narrowly defeating the Pier 39 sea lions in a vote to become San Francisco’s official animal. As the San Francisco Chronicle put it, “They’re loud, colorful newcomers that help shape the city in their bold image — just like so many of our greatest residents.” The flock is also spreading to the suburbs, recently spotted in the town of Brisbane just south of S.F.

Perhaps the most fascinating thing about these parrots is that they appear to be on their way to developing into a unique species. At least one mitred conure (Psittacara mitratus) joined the cherry-headed conure flock at one point, which is now “dotted with hybrids.” The mitred conure is also from South America, but its native range is on the opposite side of the Andes from the cherry-headed conure, so they’ve never been known to interbreed there. Perhaps in a few decades, the “San Francisco conure” will be genetically and behaviorally distinct enough to be widely recognized as its own species!

Los Angeles & Texas

Southern California is home to more than twenty recently arrived wild parrot species, but the case of the red-crowned amazon parrot (Amazona viridigenalis) is particularly noteworthy. They’re a globally endangered species native to the lowlands of northeastern Mexico3, but there are now likely more of them living in Los Angeles, with an estimated 3,000 in California and possibly less than 2,000 left in Mexico. The California population also appears to be rich in genetic diversity, and seems to be growing. A 2023 study also found that there now seem to be four roosts of the species in southern Texas as well!

Although their loud choruses of squawks each dawn and dusk occasionally excite comment from local residents, it’s becoming common knowledge that they represent a “rescue population” vital to the future of their species. The title of one LAist article summed up the situation pithily: “Pasadena's Screaming Parrots Are Super Annoying But May Save Their Species From Extinction.”

And following the broader pattern, the many species of wild parrots newly established in Southern California have inspired some devoted local fans. The Free-Flying Los Angeles Parrot Project (FLAPP), a community science network using the iNaturalist app, has registered over 7,800 observations from 2,000 individual observers. Residents and police responded quickly to a report of someone attempting to capture them for the pet trade. At least one parrot rehabber has actively defied the law to patch up injured parrots and re-release them into the wild, despite their technically being an invasive species. The red-crowned amazon parrot seems to have found a new and welcoming homeland, with plenty of room to expand in the coming decades!

Phoenix

Rosy-faced lovebirds (Agapornis roseicollis) are native to the Namib Desert of southwestern Africa, but a thriving population has established itself in Phoenix, Arizona, possibly descended from lovebirds released from an aviary by a storm in the 1980s. There are now estimated to be at least 2,000 individuals, often spotted nesting in palm trees and saguaro cacti.

And they’re smartly adapting to the unique conditions of the 21st century, with researchers finding that when climate change-supercharged heat waves hit, the lovebirds flocked to large buildings’ air conditioning vents to take advantage of the cool air leaking out. Interestingly, while they’re now common in the city, they haven’t managed to expand into the desert and scrubland surrounds, suggesting that they’re actually dependent on human-shaped environments as their habitat in the New World. A true “anthropophile” species!

Tampa Bay, Los Angeles, Tempe, Phoenix…

The Nanday Parakeet (Aratinga nenday) is another “biggie” among the American feral parrots, behind only the monk parakeet and the red-crowned amazon in a recent survey of sightings. Native to South America’s Pantanal wetlands, the species occupies many of the same areas as the monk parakeet but doesn’t seem to venture as far north in such great numbers, spreading across warm parrot-friendly spots like Florida, Texas, and California. They seem to be particularly in evidence around the Tampa Bay area, and Arizona ornithologists reported a while ago that they may be on their way to becoming the second major immigrant parrot population in the Phoenix area, joining the rosy-faced lovebirds.

Miami

Miami, in addition to many other “immigrant” parrot species, is home to a small but persevering population of magnificent blue-and-yellow macaws (Ara ararauna). While doing very well in their homeland of South America, there’s only a small flock, perhaps around 20 individuals, in Miami, and their future in the city is much more uncertain than most of the other populations in this article. In Florida, unlike California, it’s not illegal to take non-native parrot species from the wild, so harmful “legal poaching” is an ongoing problem for the Miami blue-and-yellow macaws. However, something seems to be working: the macaws have been in the city for decades and poaching has been a threat since at least 2015, but plentiful iNaturalist reports prove that the macaws are still around, perhaps thanks to a local resident working to raise awareness about their plight who has already inspired some municipal-level pro-parrot ordinance. Here’s hoping these beautiful birds thrive and eventually expand their numbers and range in the Sunshine State!

An Enriched World

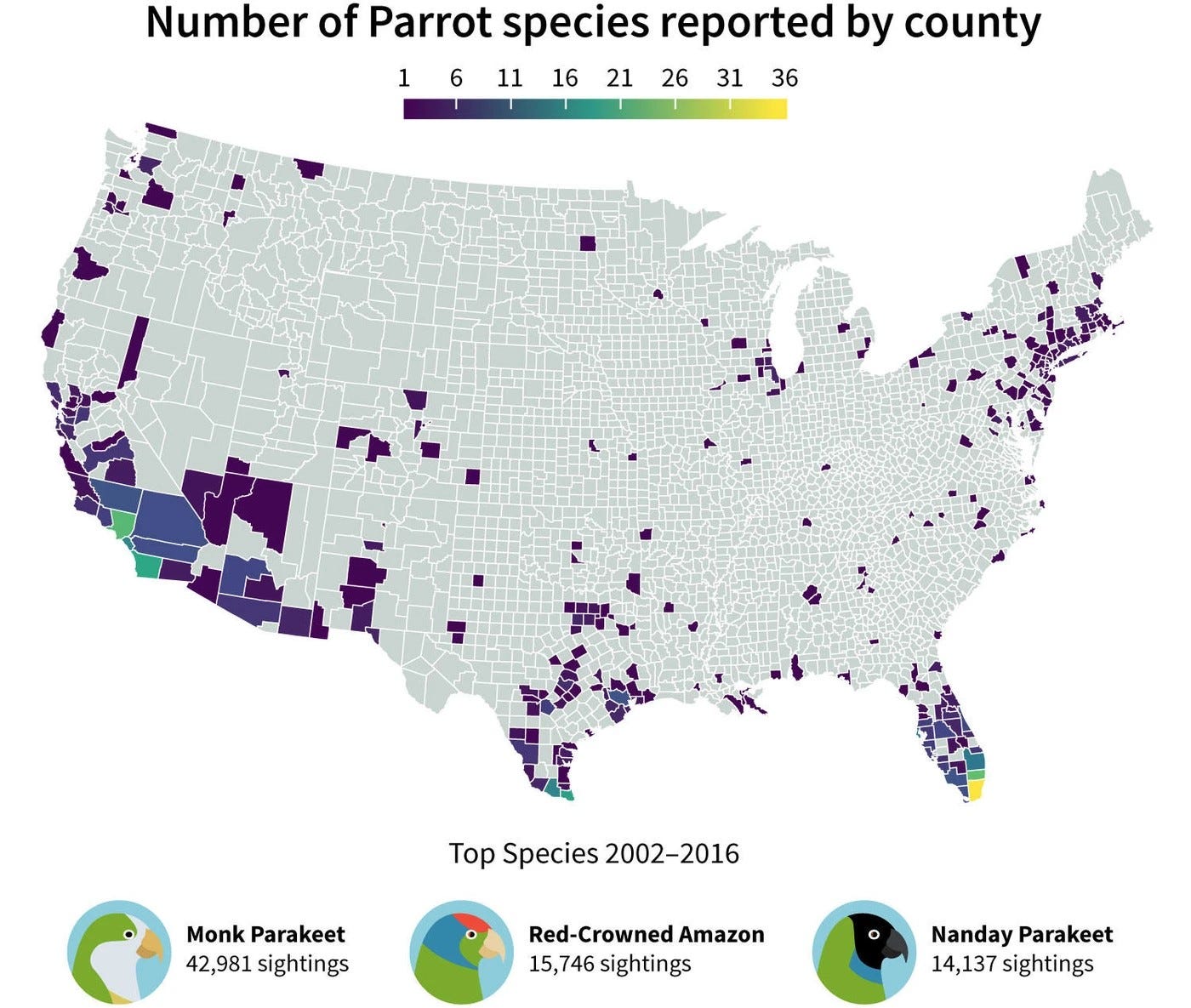

This article is the merest amuse-bouche to the wonderful world of wild “immigrant species” parrots in human-dominated landscapes. As shown in the map above, a recent survey of parrot sightings found that some counties in the warmer parts of the United States are now home to dozens of different parrots, with 25 species now breeding in different parts of the nation. America is now rich in parrots! This writer hasn’t found a similar study or map for Europe or urban East Asia, but things seem to be headed in broadly the same direction.

This biological efflorescence of parrots in cities is such that this writer would like to propose that it be seriously considered as a proactive parrot conservation strategy, building on the existing series of happy accidents. Surely there’s a warm, park-filled city in the American Sunbelt that would benefit from hosting a backup population of scarlet or hyacinth macaws, perhaps even the extra-rare Spix’s macaw if the captive-bred stock gets large enough? You’d want to pass the necessary protective legislation and get community buy-in in advance, but as a tourist attraction it might pay for itself. Elsewhere, the Puerto Rican amazon and Philippine cockatoo are both critically endangered species, but their populations have been increasing recently and it might be worth checking if San Juan or Manila (or indeed Savannah or Singapore) could host a few. As the experience of many other parrots in many other cities has shown, the upside could be immense!

To be fair, occasionally someone expresses concern about urban parrot populations in one city or another, wondering if they compete for nest holes with native birds or cause some other possible harm. Rose-ringed parakeets in particular have been found to compete with some native species for nest-worthy tree cavities and spots at bird feeders (in the Anthropocene, that counts as an ecosystem resource). Monk parakeets, while they build their own nests, may have become a crop pest in parts of Spain.

Fundamentally though, if having flocks of parrots enlivening our urban ecosystems is wrong, I don’t want to be right. Other species, from pigeons to starlings to herring gulls, have some negative effects too, and they’re still more-or-less accepted as part of the modern urban fabric. The presence of wild parrots of Anthropocene cities is a gift, a marvel of beauty and intelligence provided by the chance alignment of a wide array of evolutionary and anthropogenic circumstances. They’re beautiful, social, fascinating birds, and it’s really awesome that they’re living their loud, colorful, social psittacine lives in the hearts of the metropolises of Earth!

Several different urban legends have emerged around how these parrots got to Britain in particular; some holding that they escaped from the set of The African Queen in 1951 and others holding that Jimi Hendrix released a bunch in London in 1968. These myths have been pretty well debunked, but they’re too good not to share.

Not to be confused with Australia’s larger and much more common sulphur-crested cockatoo, although they’re doing great in cities as well!

Yes, they’re called Amazon parrots but they’re not from anywhere near the Amazon rainforest, although some of their relatives are. Yes, it is confusing.

Lovely! While living in the Sydney suburbs in the 1980s, I was visited daily by a pandemonium of rainbow lorikeets. They came to drink from a pan of water I placed on the balcony. Occasionally, they would venture a few feet into the apartment to have a look. Of course, that was Australia and you didn't have to venture far to hear the sound of birds. In visiting Adelaide, I recall that galahs, pink and gray cockatoos, were as common a pigeons in NYC parks.

This is fascinating info to learn! I saw a parrot on a power line near our house in Portland three winter's ago. It didn't have much coloration and wasn't huge, but it's beak and green color was a give-away. Probably a monk parrot, judging from the photos in your article. I remember being very worried how such an obviously tropical bird would make it through the winter! I hope it did!