Unpaywalled Book Review: The Lathe of Heaven by Ursula K. Le Guin

A classic of science fiction and a powerful reminder of how much progress we've made since the 1970s

Classic sci-fi and fantasy maestro Ursula K. Le Guin is perhaps best known for her Hainish Cycle and Earthsea series, but my favorite of her works1 is a standalone book: The Lathe of Heaven, first published in 1971. I first came across a tattered copy in the impromptu library of the Kianjavato Ahmanson Field Station in the eastern forests of Madagascar in 2019, part of a collection of literature donated by previous volunteer research assistants, and it was a truly delightful read. Somehow, this book manages to be a catalogue of 1970s-era worries about social and environmental catastrophe, a Taoism-inspired philosophical meditation on the nature of reality, a suspenseful page-turning read, and on top of all that a counterintuitively comforting and reassuring reminder of how human ingenuity can solve seemingly intractable problems.

Full review now unpaywalled!

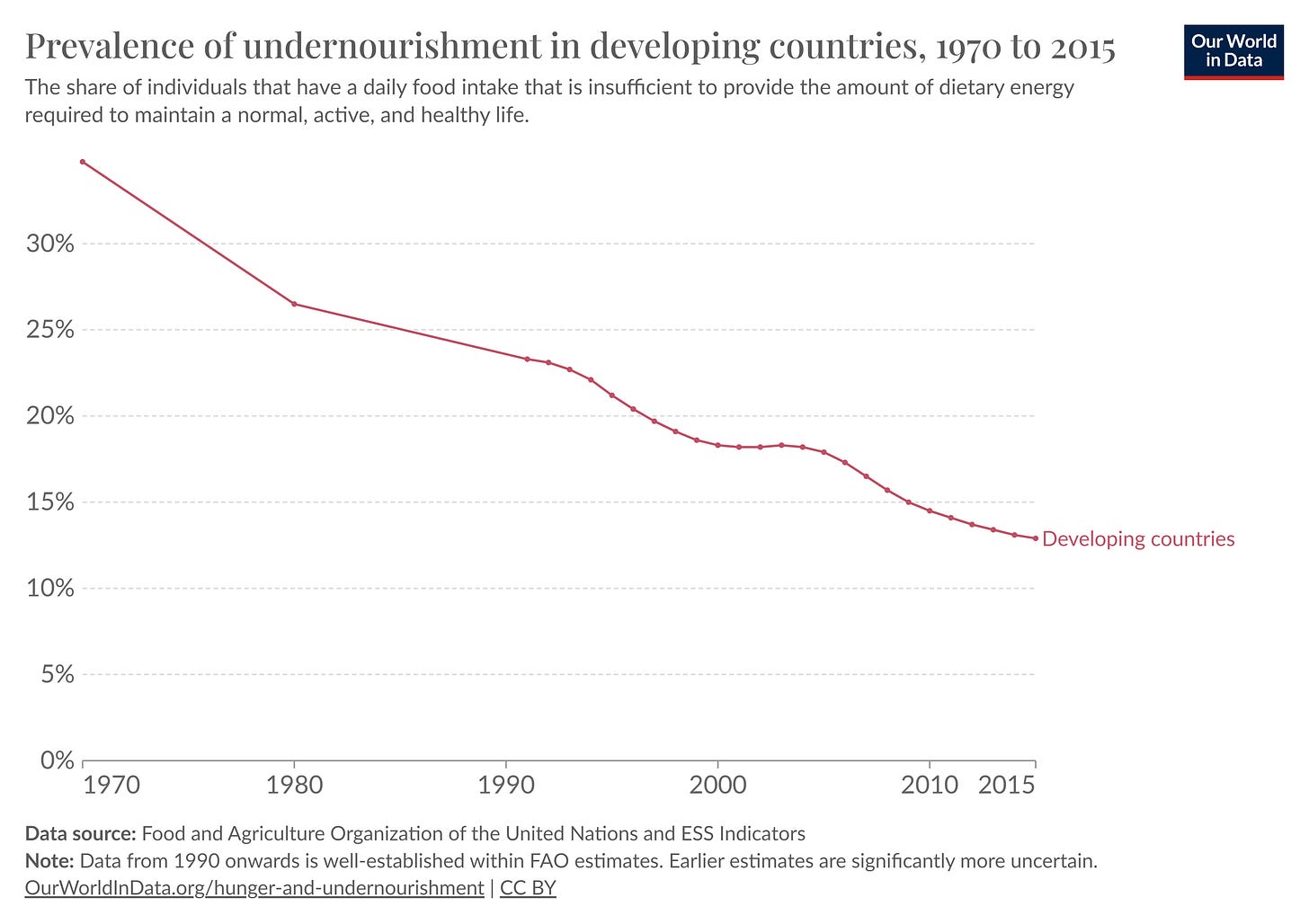

As I recall, the book starts in a dark alternate Earth: a hyper-overpopulated Malthusian nightmare future straight out of Ehrlich’s failed predictions (which seemed very plausible when this book was written), where famine and war ravage the warming, polluted globe and food supplies just keep getting scarcer. The main character, George, lives in a Portland, Oregon where children on the street are dying from kwashiorkor, the real-world panoply of disorders that arrive when a human body has a critically low protein intake. (A chill went through me reading this in a subsistence agriculture-dependent region of a developing country; helping renew my respect and gratitude for modern civilization’s great and ongoing victories against the ancient and insidiously quotidian horror of hunger. In the real world, children dying of hunger is getting rarer and rarer, and that is a civilizational achievement worthy of solemn and joyous profound celebration). Aside from general despair at the state of the world, George has a more specific problem: he believes he’s going insane, because every time he goes to sleep and has a dream, the world seems to change somewhat to match the dream when he wakes up, and he’s losing his sense of reality. His psychologist, Dr. Haber, an incarnation of mid-twentieth century “father knows best” High Modernism, immediately takes charge of a “cure,” hypnotizing George to sleep, telling him to dream of a change in the painting of a horse he has on his office wall, then waking him up to show that the painting of a mountain is completely unchanged. Wait a minute….

George is just relieved that someone else sees he’s not crazy, but Haber has bigger dreams: a reality warper has turned up on his doorstep, all trusting and ready to let himself be hypnotized! What better moment for a Man of Destiny to set the world to rights? Most of The Lathe of Heaven follows the escalating sequence of this, allowing a brilliant “flipping through pages” look at alternate sci-fi futures. And a fascinating ride it is, because every time George dreams a change in the world, it has unintended consequences.

To start with, the sinister Dr. Haber urges him to fix the world’s overpopulation crisis, hypnotizing him to dream of a green, plentiful world with plenty of room for everyone. As might be expected by a modern reader familiar with the trope’s use in subsequent media, George awakes to find not that more resources or, better, new innovative technologies have been created, but that he’s Thanos-snapped a majority of humanity out of existence, retroactively changing the timeline such that it has always been this way. (George comes across as a pretty decent guy overall, but really gullible and suggestive, remaining a pretty sympathetic character because he’s genuinely aghast when his dreams create horrors and gradually loses his trust that Haber will fix it all in the next session). Somehow that fails to make the world a utopia, so Haber has George keep plugging away on solutions to the obvious problems he sees. George dreams of abolishing racism…and he wakes up to find that everyone in the world has, and has always had, a uniform gray skin tone. Worse (for him personally, at least), his love interest Heather has disappeared: her parents met at a 1960s civil rights rally.

People are still imperfect even when they all share a skin tone, though, so Haber decides the roots of the problem are deeper, and starts seeing ways to describe possible futures to George that will generate unintended consequences to his advantage. Softly sketching a plausible-seeming “sensible regulation of breeding” to George under hypnosis, a few more dreams and awakenings result in a world run by a totalitarian Science Directorate straight out of 1930s technocratic fascism, with Haber now the head of a Eugenics Department and an Institute for Oneirology (the study of dreams) in Portland, capital city of Earth.

It’s still not enough; Haber urges him to dream that humanity is finally united as one. He does…and giant alien ships arrive, landing on the Moon and producing unprecedented global unity against a terrifying potential foe. Damage control time: George desperately dreams that the aliens are no longer on the moon…and wakes up to announcements that they’ve landed on Earth. And then things get really interesting, because the aliens actually recognize George’s dreaming as a known class of phenomenon, the Lathe of Heaven through which reality shapes itself. Finally, someone has a clue what’s going on here! (That’s enough plot spoilers for now, go read the book!)

The most glorious part of the novel, for me, is how it ends. After the imaginative climax where Haber is defeated and the reality-warping dreams end, Earth doesn’t snap back to “the normal way the world should be.” As Le Guin acknowledges, there is no “normal way the world should be” in this crazy yet wonderful Anthropocene epoch of ours. Humans are talking apes wearing clothes who have reshaped their home world and are starting to dip toes into space: there’s no “normal” to go back to. And nor should we want to: “normal” is kids dying of kwashiorkor after a failed hunt or bad harvest year. A repressed childhood memory of George’s serves as a brilliant analogy for this: in the world of The Lathe of Heaven, the closest thing to a “true” or “original” reality, pre-dreaming, is the aftermath of an apocalyptic nuclear war. George eventually remembers that his first reality-warping dream occurred when he was a small child dying of radiation sickness in a nuked Portland. As bad as many of the alternate Earths were, they were better than that.

So after the climax, instead of a boring “then he woke up and realized it was all a dream within a dream” ending (I find those distasteful!), George steps outside to find a richly kaleidoscopic new reality incorporating elements of all the previous ones he dreamed up. There’s still some of the nice green spaces and wild land from the low-population world, but a high human population is better integrated: I seem to recall it’s implied that some of the birth-control tech from the Science Directorate-y world sticks around but is optional now. Gray-skinned people are just another ethnicity among many, mostly found in Central Europe and the American Midwest. Some of the turtle-like aliens are just hanging out on Earth as small-time traders and/or inscrutable wandering mystic tourist/gurus; one lives in his neighborhood and seems to remember more of what’s just happened (or un-happened) than the humans do. And, an unexpected joy for George; Heather is back: she doesn’t know George anymore, but she exists, and there’s a chance that they could get together in the future.

That’s the book. It’s a really good book! From one perspective, it’s lost some of its punch these days because it’s very much “of its time” and can seem outdated: many people now worry far more about human population decline than human population growth, as fertility rates are dropping sharply around the world. But I would argue that as time has gone by, The Lathe of Heaven has actually taken on a whole new meaning that enriches the reading experience. As its featured fears receded into the past; it’s become a fascinating time capsule of what smart people in the mid-20th century were extremely worried about. The litany of horrors George dreams up really did seem like very plausible near-term futures in the 1970s. Reading books and articles from the time gives a sense of a broad-based horrifying feeling among many intelligentsia of the time that dystopian tradeoffs were inevitable, that we’d either have Malthusian mass famine or totalitarian control of all reproduction, and probably lots of both. The fact that we have a population of over eight billion humans as of 2024 would have seemed a sure indicator of apocalypse to many. Make Room! Make Room!, the 1966 science fiction novel that inspired the movie Soylent Green, posited that a population of just seven billion would have caused total environmental collapse, with only the infamous ration left as a food source for the starving multitudes.

As it turned out, human beings have brains as well as stomachs. Writing about the book in the 2020s gives this writer an immense feeling of thankfulness for the great advances that have already been won, a “saved from the scaffold” feeling. The Green Revolution was just getting underway when LeGuin was writing The Lathe of Heaven; it wasn’t yet clear that Norman Borlaug’s drought-resistant wheat and its clever successors had staved off the feared famine. Even today, as climate disasters escalate, food production is keeping pace with disruption and we’re seeing record-high yields of many staple crops. Human civilization as a whole is nowhere close to starving! We take that for granted now, but it would have seemed a beautiful dream in the 1970s.

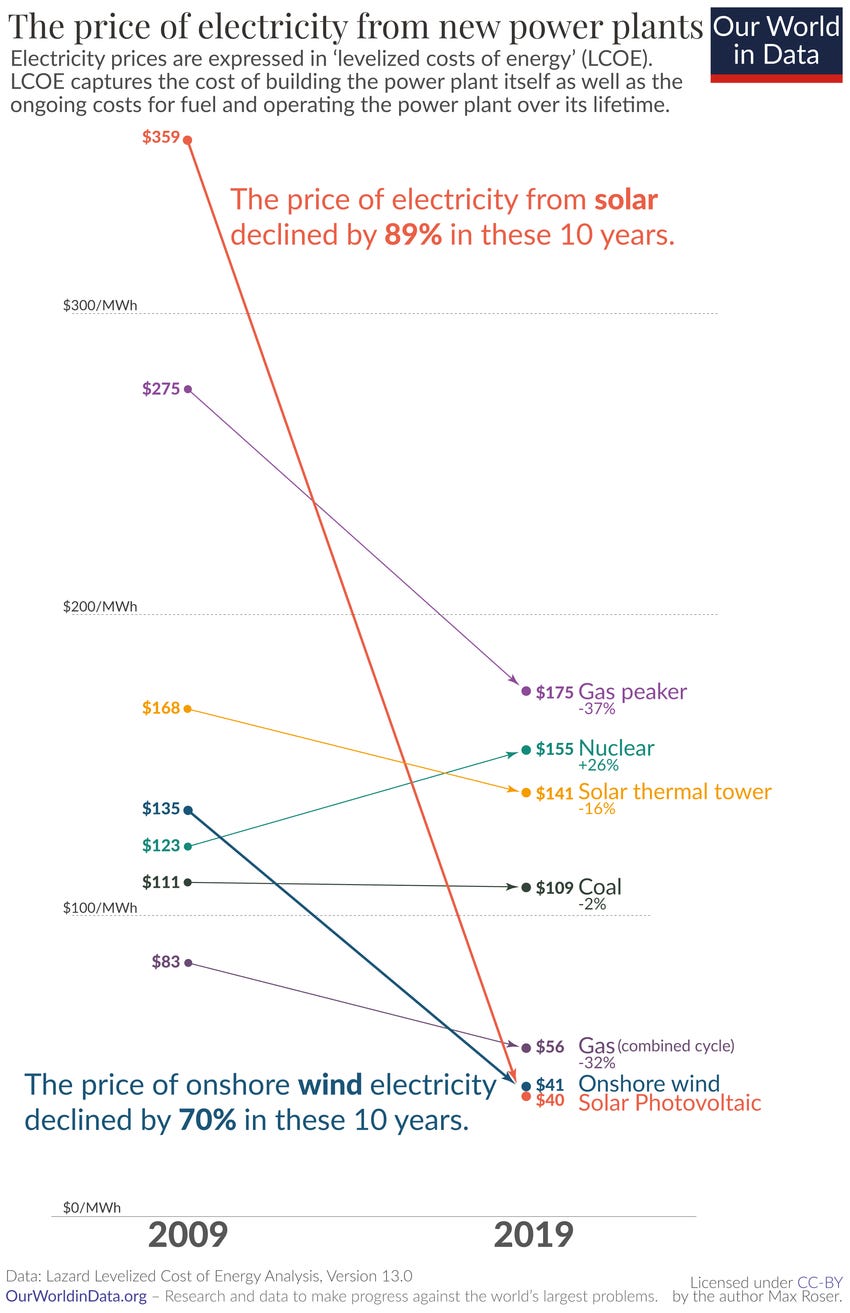

And it’s starting to look like some of the worst fears of the 2000s and 2010s will eventually fade out of the realms of realistic fear and fade into gibbering shadows of alternate histories like the ones in The Lathe of Heaven. In particular, this writer is really jazzed at the fact that the recent rapid advances in renewable energy technology mean that we are clearly on course to avoid RCP 8.5, the “worst case scenario” IPCC climate change forecast that guided a lot of the scariest studies and projections. RCP 8.5 models what would happen to the atmosphere if global greenhouse gas emissions keep rising for the rest of the 21st century (the “we keep building new coal plants instead of renewables” scenario), only peaking and starting to decline sometime after 2100. That would have led to a truly catastrophic degree of warming, potentially as high as 4°C to 6°C by 2100, which would have caused civilization and biosphere-threatening consequences. This looked very, very plausible as recently as 2010, before the epic innovation-driven price declines in solar and battery technology led to a global clean energy boom.

As of late 2023, according to the International Energy Agency, it looks like global carbon dioxide emissions will peak in 2025 or sooner (perhaps 2023 was the peak, at the rate we’re progressing!) and we’re on course for around 2.4°C of warming by 2100, with the potential for better outcomes if we keep improving. Hopefully, future generations will look back on RCP 8.5 as we now look back on predictions of mass Malthusian famines in the late 20th century: as a possible “self-denying prophecy,” a warning of a future that seemed scarily close at the time, but that great advances have allowed us to definitively avoid.

To be clear, saying that we might one day look back on worst-case-scenario climate change as a threat we mostly avoided is not to say that climate change will magically fix itself, or that climate disasters and shifts won’t cause horrible suffering. No doubt many bad, dystopian, sucky things will still have happened in some places! But many bad, dystopian, sucky things have happened in our world too, and we’ve managed to still build an unprecedentedly good world. We should strive to limit and prevent suffering as much as we can, but saying “some bad things will happen and it’s up to us how we respond” is very different from saying “everything is doomed to be bad forever.” We did get some of the horrors from George’s dreams in real life even without a global overpopulation crisis: China’s longstanding (and eventually hastily abandoned) one-child policy was as cruel and coercive as anything Haber could cook up. Famine struck Somalia in recent years. But by and large, we’ve avoided them. We’ve found a better way.

I believe, strongly, that despite the challenges Earth and humanity face, the world overall will continue getting better. We as a species—heck, as a biosphere, with everyone from whales to soil microbes lending a hand, flipper, or cilium—can and will deal with climate change. We can have a prosperous, creative, 100% clean-energy-powered, no-kids-dying-of-kwashiorkor global technological human civilization, with a rich and thriving biosphere that humans have helped survive and adapt to a warmer world, a task made easier but an atmosphere that’s finally stabilizing due to negative or negligible anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. That may seem implausibly optimistic. But I don’t think it’s any more implausibly optimistic than our current reality, the record-crop-yields, fertility-rates-dropping, no-nuclear war world of 2024, would seem to someone reading The Lathe of Heaven in the 1970s. And that is why you should read this book. It has the power to inspire gratitude for the world we have and hope for the one we can build.

Another overlooked Le Guin gem is her children’s fantasy series Catwings, which I absolutely loved as a kid. I’m also a big fan of Rocannon’s World, the “Semley’s Necklace” introduction of which explores what relativistic time dilation might seem like to inhabitants of a low-tech “fantasy-world” planet to strikingly powerful effect.

I've never read the Lathe of Heaven, but after reading this review, I will. Le Guin lived in Portland of course and I met her once at a bookstore there where she was perusing the shelves as a customer. I recognized her and rudely interrupted her browsing to blather about how much I had enjoyed her Earthsea books. She endured the fanboy adulation diplomatically...

My brother in law really esteemed her novel, the Left Hand of Darkness which I had never read. Still haven't. Reading hard Sci-fi was always more my métier.

Loved this book and this post! You caught things I missed from the book. It’s nice to be reminded of hope in a big picture way too.