Unpaywalled Book Review: Indigenous Continent by Pekka Hämäläinen

A fascinating deep dive into the long-lasting power of Native nations in North America

I hadn’t planned to write a review of Indigenous Continent, but I saw a copy at my local library, and then I was inexorably going to do so. The book demanded my attention, then successfully held it. A one-volume history of the Indigenous nations of North America, this chef d’oeuvre brilliantly integrates the decades of new scholarship that have forged a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

For example, the book has a delightfully ecological bent, explaining how life-forms like kelp, corn, squash, beans, salmon, acorns, bison, beaver, and horses were vital to Indigenous life in North America. Kelp forests likely provided the first major highway for humans to arrive in the Americas, with fish, shellfish, and marine mammal-rich marine ecosystems providing sustenance for Pacific Rim voyages even while what is now Alaska and Canada were thickly glaciated. Salmon became the primary food source for the Pacific Northwest peoples, shaping hierarchical kingdom societies based on control of key salmon rivers, while acorns became the primary food source for peoples in what is now Northern California, shaping more egalitarian societies spread across plentiful oak groves. (This absolutely fascinating salmon/oak nation distinction is further discussed at length in modern anthropology classic The Dawn of Everything). Corn, squash, and beans were the symbiotic “Three Sisters” of North American agriculture, the core crop of lands from the Pueblo to Cahokia to the Wampanoags, providing a balanced diet while keeping the soil fertile. Beaver pelts were the core trade good of North America for centuries, with pelts exchangeable at French, Dutch, and British trading posts for everything from cloth to scissors to kettles to guns & ammo.

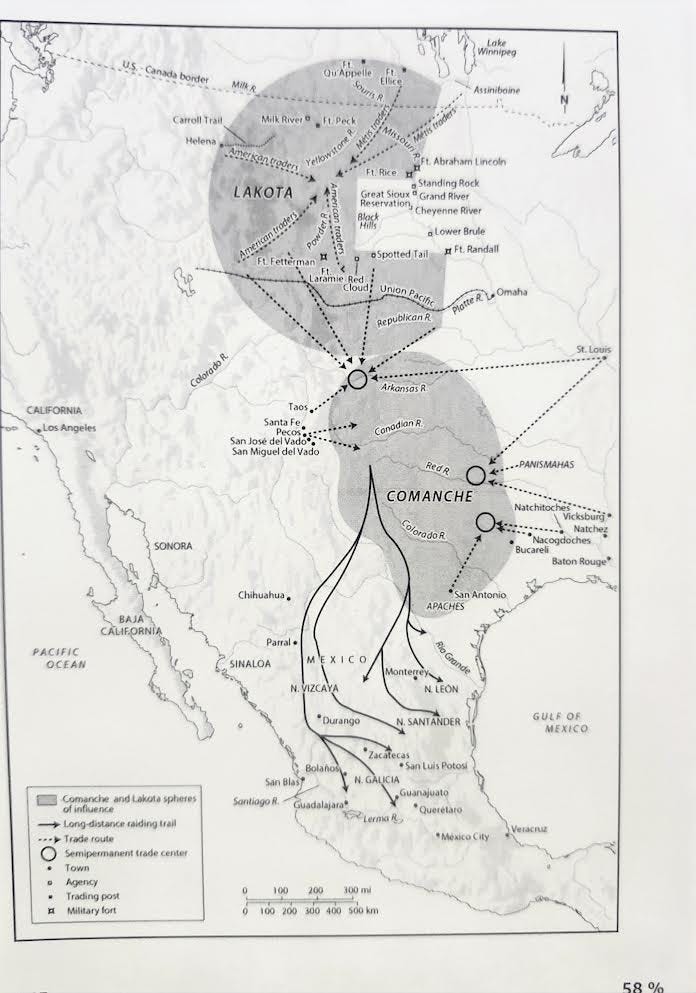

And horses…well, horses changed everything. Native Americans previously had dogs as their main domestic animals, and they weren’t nearly as useful. Dogs have to be fed meat from herbivorous animals: they’re a high-trophic-level species, with big energy losses between photosynthesis and usable animal work. Horses (in a delightful detail, the Comanche called them “magic dogs”) are one trophic level down, and thus could more directly access the immense caloric resources of the vast grassy Great Plains with less energy losses. As Hämäläinen eloquently puts it, “The horse was a bigger and stronger dog, but, more profoundly, it was an energy converter. By transforming inaccessible plant energy into tangible and immediately available muscle power, horses opened up an astonishing shortcut to the sun.” This allowed much more effective hunting of bison, enabling the rise of nomadic, ultra-bison-dependent “horse rider nations” like the Lakota, Comanche, Crow, and Blackfoot. The Comanche actually focused their food-production activities so intensely on hunting bison that at one point that they traded with sedentary Native peoples for almost all of their carbohydrates, swapping protein and fat-rich bison meat for Three Sisters crops (and by then, European imports like bread as well).

Full review now unpaywalled!

The book also presents a fact-based and data-rich portrait of Indigenous and settler geopolitics. Indigenous Continent doesn’t subscribe to the mirror-image dehumanizing myths that Native Americans as one-dimensional stereotypes, either brutal savages (more common in the 1800s and early 1900s) or noble forest elves (more common in the late 1900s and 2000s so far). Indigenous nations tortured prisoners, massacred civilian families, conducted human sacrifices, and traded slaves, occasionally nearly as much as the Europeans did. The book’s writing style does slant towards seeing things from an Indigenous point of view (in Indigenous Continent’s prose, settler attacks on Natives are driven by “fear and hate,” while Native attacks on settlers are “communicating through violence”), but this is frankly welcome, providing a valuable counterweight to the multitude of works that deemphasize Indigenous power to paint them as either brutal barbarians or childlike victims.

Indigenous Continent tells the story of Native Americans across essentially all of the modern United States and Canada, from the salmon kingdoms of the Pacific Northwest to the swamp-savvy Seminoles of Florida. But the stories of the Iroquois (aka Haudenosaunee) and Lakota stand out particularly vividly. In the late 1600s and early 1700s, the Iroquois League was the dominant power between the Mississippi and the Atlantic, expertly playing the French and the British off against each other to secure manufactured goods (including, vitally, abundant firearms) on preferential terms. In the wake of population-ravaging epidemics, the original Five Nations of the Iroquois League launched “mourning wars” for captives from other Iroquoian-speaking nations to replenish their population, forcibly absorbing much of the Wyandot (aka Huron), the Erie, the Susquehannocks, and other peoples, then admitting the Tuscarora as an equal Sixth Nation. In the process, they underwent their own “westward expansion” from their homelands in (what is now) New York into what is now Ontario, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. Indigenous Continent puts forth very strong evidence that the Iroquois were the pivotal power on the continent for most of the 1600s and 1700s, taking on the characteristics of an empire and an equal to the British and French Empires. This quote gives context to their global reach: “In 1710 the Iroquois League sent four envoys-Tejonihokawara, Sagayenkwaraton, Onioheriago, and Etowaucum-to London. Queen Anne received them at St. James’ Palace, where they shared their grievances with the British sovereign. Dubbed as “The Four Kings,” they dined with William Penn and other London elite and were received by the archbishop of Canterbury.”

The eventual (very limited and conditional) entry of the Iroquois League into the Seven Years’ War on the side of the British (the North American theater of which was also known as the French and Indian War) was a major deciding factor in the eventual British victory. The age of Iroquois supremacy lasted until the American Revolution, which was also a devastating “Iroquois Civil War” in which some of the Six Nations sided with the American rebels and others with the British. Even after that, Iroquois brother and sister Joseph and Molly Brant (aka Thayendanegea and Konwatsitsiaienni) were key to putting together the first iteration of the Indian Confederacy in the 1790s, a serious rival to the fledgling United States at the time.

The Lakota, in the form familiar to history, were arguably founded in 1776, when Lakota explorers from the areas around what is now Minnesota reached Paha Sapa, the sacred Black Hills which eventually became their new capital (more or less), starting another Indigenous “westward expansion” and the eventual conquest and imperial consolidation of the Missouri River Valley. As the book puts it, “In 1776, according to American Horse [a later Lakota elder], two nations had been born in North America, both destined for discoveries of new worlds, dominance, military glory, and finally, a terrible, violent clash with each other.” The Lewis and Clark expedition was only possible because the Lakota granted passage along the Missouri River they controlled. They remained a major power through the 1870s.

Reading previous works on Native American history, from American Colonies to 1491 and 1493, this reviewer had often been confused by space and time. Where, exactly, were the Shawnee and the Lenape located? What happened to the Apalachee, and where did the Seminoles come from? Don’t the Apaches and the Comanches seem to have the same described homeland? Who was living where, when? Indigenous Continent spells it all out in painstaking detail, providing the necessary context and big-picture summaries that make it clear: Native American nations were often highly mobile and proactive, moving fast and far across the continent to escape settler violence, forming new nations from scattered survivors of epidemics, and strategically uniting and dividing in response to the geopolitical and ecological context. The Seminoles were formed from the survivors of several Florida peoples devastated by epidemics, including the Apalachee, joined by escaped Black slaves. The Comanches came in from the north and drove the Apaches from lands that are now in New Mexico and Texas to lands that are now in Arizona and Northern Mexico: as the author succinctly states, “the old Apacheria became Comancheria.” The Shawnees and Lenapes took off on epic journeys to try to stay one step ahead of colonists: the Lenape people, originally from the New York/New Jersey/Pennsylvania area, ended up on reservations as far afield as Wisconsin, Oklahoma, and Ontario after generations of migrating westward to maintain their independence.

This writer had thought of the European colonization of the Americas as essentially inevitable in the long term, given the technological disparities and Eurasia-nurtured epidemic diseases. But Indigenous Continent persuaded me that it was a lot more complex and contingent than that. Sometimes, Indigenous Continent gives the feel of a history book from an alternate history, maybe a timeline where multiple Native American nations retained full sovereignty on their original homelands and the United States evolved a looser, multicultural, European Union-like format. It does this not by falsifying history, but by reversing the emphasis of “traditional” American history textbooks where Indigenous victories are portrayed as “speed bumps” to settler expansion, anomalous delays of the inevitable. The thing is, there actually were a bunch of really resounding and impressive Indigenous victories, and at several points it looked very possible that Indigenous peoples would retain control of substantially larger parts of the continent than they ended up doing! There’s a strong case to be made—and Indigenous Continent makes it persuasively—that at several key points in the history of North America, European colonies were essentially tributary states on the outskirts of Native American empires, providing guns, cloth, and metal tools in exchange for protection, food, and trade goods (for centuries, mostly beaver furs).

Indigenous Continent points out that for centuries, most European victories against Indigenous nations were only possible because other Indigenous nations were fighting on the European side, from the Tlaxcala people that sided with the Spanish in the conquest of Mexico in the 1520s to Apache scouts helping force the Chiricahuas into a reservation in the 1870s. The book makes a solid case that this sort of thing wasn’t so much Europeans pulling off a “divide and conquer” strategy as Native Americans successfully manipulating Europeans into unleashing superior technology on their traditional enemy nations. Most Native Americans didn’t start thinking of themselves as “Native Americans” until the late 1700s at the earliest; the Europeans were just new players in a preexisting complex geopolitical system, and they were often very useful in helping one Indigenous nation gain ascendancy over others. While the long-term impacts of entrenched European settlement often harmed their erstwhile allies, Indigenous nations that fought alongside Europeans often reaped substantial gains. The book discusses several occasions where a nation enjoyed a half-century or so of being staunch European allies and preferred trading partners. That represents periods where people enjoyed generations of prosperity and peace.

And there seemed to be several points where the overall macro-contest for the continent really could have gone the other way. For example, the 1670s and 80s saw the Great Southwestern Revolt (aka Pueblo Rebellion) successfully kicking the Spanish out of New Mexico, a Susquehannock offensive driving the slave-trading Virginia colony into civil war with settlers against settlers, and Algonquian-speaking peoples from the Narragansett to the Wampanoag to the Wabanaki uniting under charismatic sachem Metacom (aka “King Philip’s War”) to drive back the increasingly hard-edged Puritan colonists of New England. If the Iroquois had intervened on Metacom’s side instead of on the New Englanders’ side, all of American history might have been different.

Later on, a multinational Indian Confederacy army under Little Turtle and Blue Jacket routed fourteen hundred U.S. Army soldiers at the Battle of the Wabash in November 1791, inflicting a 97.4% casualty rate. Indigenous Continent was the first time this writer had heard of “the most decisive defeat in the history of the American military,” which doesn’t get much emphasis in most history books. Nor did the aftermath of that battle, in the discussion of which Indigenous Continent drops the perception-recalibrating sentence, “Unable to defeat the allied Indians in battle, the president of the United States relied on terror and total war, targeting noncombatants, fields, orchards, and trade centers.”

Right up until the 1810s and the fall of Tecumseh’s second-generation Indian Confederacy, some kind of independent Indigenous nation east of the Mississippi looked very possible.

However, Indigenous Continent doesn’t shy away from the reality that however powerful and innovative they might have been in their prime, the Indigenous nations of North America were all eventually eclipsed by the growing United States and Canada. After the last hurrah of the Battle of Greasy Grass in 1876 (aka Custer’s Last Stand, where the Lakota under Crazy Horse defeated the Seventh Cavalry), Indigenous nations were no longer capable of winning these wars, not against ever-growing late-Industrial mega-nations equipped with telegraph lines, railroad networks, and a policy of deliberate industrialized bison slaughter to cut the Great Plains nations’ food supply out from under them.

Yet the book takes an unusual “glass half full” view of Indigenous America in the twentieth century, pointing out that to have secured legal rights to reservations was no small accomplishment, and represents not a gift from the U.S. or Canadian governments but a hard-won concession, an acknowledgement that there was no more political will for European settlers to fight wars of extermination to the bitter end. As Hämäläinen points out, “The continent is speckled with hundreds of Native nations that preserve Indigenous sovereignty and nationhood.”

And several recent events seem to be bolstering this viewpoint. To stretch a naturalistic analogy, one could view the Native American reservations as tough-shelled “seeds” that can endure hard times and later sprout in more favorable conditions. The Lakota, Navajo, Cherokee, Squamish, Seminole, Wabanaki, Yurok, and multitudes of other nations successfully avoided the dreadful fate of the Beothuk and the Tasmanians when settler violence was at its height in the 1800s, and in the more Native-friendly 21st century are beginning a cultural and political renaissance.

In the early 2020s alone, this newsletter has observed several epic Native victories, including the brilliant inventiveness of the Squamish Nation’s under-construction clean energy skyscrapers at the Senakw Project, the Yurok Nation’s restoration of the California condor on their ancestral lands, and the historic appointment of Deb Haaland as the first Native woman to be United States Secretary of the Interior, with excellent work since.

What can these seeds grow into? What would be a good analogy for these dispersed yet deeply-rooted Native lands sprouting new endeavors, from wildlife reintroductions to solarpunk cities? A distributed autonomous network? A pointillistic painting? A circulatory system to bring new nutrients to the hundreds of millions of peoples with ancestors from around the world now sharing the continent? A sturdy foundation to build on? This writer is excited to live through the next chapters in the story of North America as an Indigenous continent.

Another really good one!

Good stuff. I, too, was fascinated by the stark difference between salmon and acorn harvesting peoples. Have you read 1491?