The Weekly Anthropocene Reviews: Wild Souls by Emma Marris

A The Weekly Anthropocene Book Review

The Weekly Anthropocene published a review of Emma Marris’ Wild Souls in May 2021. The interview is now republished (with a few text & image updates) for Substack!

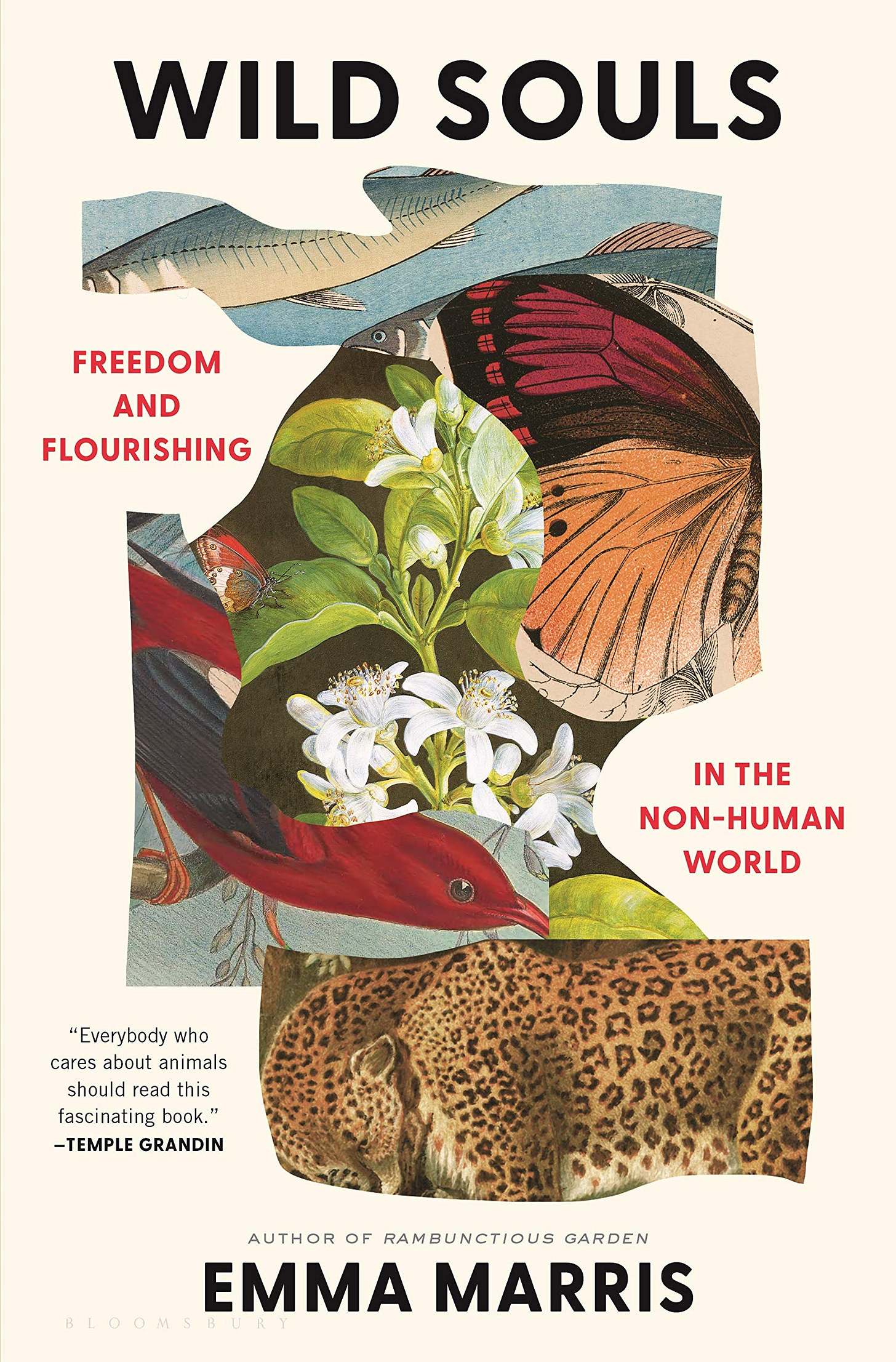

Emma Marris is a renowned environment, wildlife, and culture writer, known inter alia for her landmark “Earth Day 2070” article in National Geographic, her 2011 book Rambunctious Garden, her debate with E.O. Wilson, and her environmental coverage for The Atlantic. In her 2021 book, Wild Souls, Ms. Marris takes on some big questions, from animal rights to the meaning of the Anthropocene to the powers and responsibilities-perhaps even duties-of humanity as a whole.

Near the beginning, Ms. Marris makes a radical, even shocking, statement which informs the inquiries of the rest of the book. "After many years, I have come to see the concepts of wilderness and nature as not just unscientific but damaging. Firstly, all organisms alive today are influenced by humans. Second, we humans are deeply influenced by the plants and animals we evolved with; we are part of "nature," too. Thirdly, "wilderness" rhetoric has long been used to justify denying land rights to Indigenous peoples and to erase their long histories. And finally, thinking of nature and humans as incompatible makes it impossible to discover or invent new ways of working with and within nature for the common good."

“Thinking of nature and humans as incompatible makes it impossible to discover or invent new ways of working with and within nature for the common good."

-Emma Marris

This is a new and potentially much-needed way of thinking about the Anthropocene Earth we live in. It can sound like a potentially very damaging ideology; this writer's first thought was that it could easily be used as a justification for anything humans feel like doing, no matter the cost to ecosystems and wildlife. But Ms. Marris walks the walk on her bold hypothesis, grappling with the complexities of issues of animal rights, sovereignty, and what we truly value and want to protect.

For example, conservation is already pretty on board with greatly decreasing a species' autonomy and "wildness" in order to save it: the last 27 California condors were captured from the wild for a captive breeding program in the 1980s, and most condors now, even those living in the "wild" outdoors, have radio tracking collars, numeric codes on their wings for easy identification from below, and receive on-site veterinary care. This is generally considered to be a good decision, as it saved the species, and would seem to indicate a moral principle that highly values preserving the lineage of a species. But the California condor louse was driven to extinction by this same program1, when those first 27 condors were deloused for their own health. And no one really cares-not even this writer, really-because it's a species of louse. This raises the question: do we only save species when we, as humans, personally like them and want them around? And is that a bad thing?

Yet even while considering such "heretical" sentiments, the California condor program can scarcely be recognized as anything other than a success. Because of it, an ancient American bird still soars above the Sierra Nevada and the Grand Canyon. We may not be able to come up with a perfect Theory of Wildness to explain this, but it’s obviously, intuitively a good thing in practice. That’s more than enough.

This author is reminded of the case of the critically endangered greater bamboo lemur (Prolemur simus) population in Kianjavato, Madagascar. They were far from a stereotypical purist’s idea of “wild”: collared with identification tags, constantly monitored, and buried by humans when dead (to prevent anyone developing a taste for their meat). Yet without these connections to the community, they would certainly not be able to coexist and even thrive alongside humanity as they do. It felt no less awe-inspiring to see them leaping between the bamboo stalks.

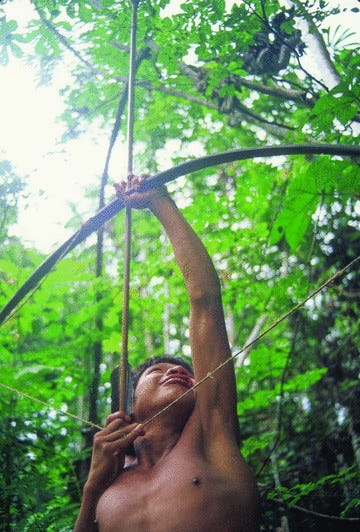

Ms. Marris travels the globe in her quest through these complex moral philosophies. One stop is a national park in Peru where the Matsigenka indigenous people live in villages within the forest-a practice far removed from traditional Western notions of a park as an inviolate, separate dominion. The Matsigenka and hunt spider and woolly monkeys within the park, as they have always done-but they voluntarily refrain from using guns, to avoid decreasing the population, and from their own self-interest serve as a 24/7 guardian force to ward off illegal loggers and miners.

And in the wilds of Australia, where vast efforts are spent killing some of the millions of feral cats, foxes, and other small-marsupial-eating predators (with little to no discernable impact), a new guard of "compassionate conservationists" is instead trying to selectively breed a tougher and more cat-savvy bilby (an adorable big-eared, hopping little marsupial that currently is easy meat for predators from other continents).

Ms. Marris also cites examples of pointless and counterproductive actions mandated by the existing legal structure that views "wild" and "species" as carved-in-stone, immutable categories, instead of the more fluid reality. A dog that ran away to join a wolf pack in Washington State was hunted down for recapture at great expense, and a female wolf he bred with was sterilized to prevent dog genes from entering the wolf population, as that could lead to legal liability questions. All this despite the fact that canids in the wild interbreed all the time; in Italy, one recent study found that over 30.6% of wild canids surveyed were wild-living wolf/dog hybrids.

Even more outrageously, the US Fish and Wildlife Service routinely kills common barred owls and spotted/barred owl hybrids in the Pacific Northwest in order to maintain the "purity" of the genome of the more threatened spotted owl. They got court approval to kill thousands more in 2022, after Wild Souls was published. This despite the fact that there is no objective value of "genetic purity,” a completely human-invented construct, not to mention early findings that these hybrid owls may actually be better adapted to survive under climate change. We [humans] are policing wild animals’ reproductive choices to make them better fit with our idea of what they should be, rather than what actually makes sense for them as a survival strategy!

As The Weekly Anthropocene has often previously written, they are in favor of finding ways for wild animals to survive that work for the animals, not for the humans’ preconceived notions, whether that means intense human conservation support, allowing harmless “invasive” species to thrive in new habitats, letting hybridization happen, or letting wild animals range into human-dominated landscapes. Wild Souls fundamentally acknowledges the complexities of these issues, and eschews easy "new rules" in favor of key principles to keep in mind when making decisions. It's a fascinating and deeply thought-provoking read. Check it out-it's worth your time!

At least four other parasite species have fallen victim to “conservation-induced extinction” as well, killed by good, caring, animal-loving people trying to keep their endangered species hosts healthy. Is this a bad thing? How, exactly? It’s clearly bad if we lose the California condor, but was it bad to lose the California condor louse?