The Weekly Anthropocene Interviews: Ayr Muir, CEO of Clover Food Lab

A company that's making seasonal, locally sourced vegetarian fast food a working proposition

Ayr Muir is the founder and CEO of Clover Food Lab, a plant-based fast food restaurant network in the Boston area with a seasonal locally-sourced menu.

Yay, a financial disclosure! This is one of The Weekly Anthropocene’s first-ever sponsored posts, thanks to Jason Ingle of Third Nature Investments (who we interviewed recently) and his work to support plant-based food and textile companies.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Mr. Muir’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

So, Ayr: what is Clover Food Labs? What do you do?

We're a fast casual restaurant chain based in Boston. Right now we have 15 locations, all in the Boston area. And we also do meal kits that we ship to people's homes, we have about 2,000 subscribers who take part in that every week.

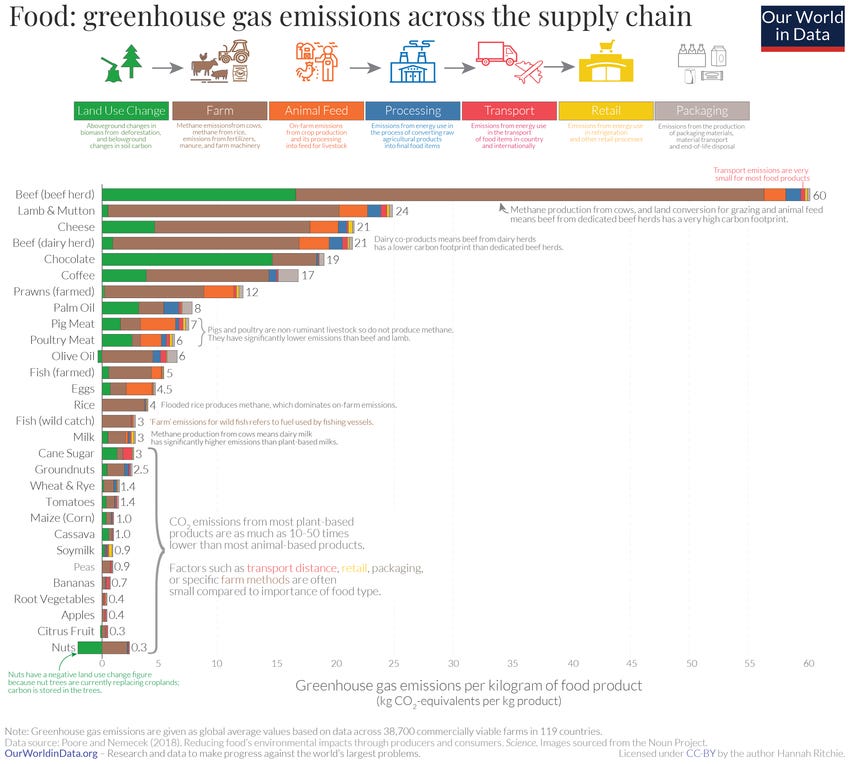

Clover is a mission-based company. Our mission is to help encourage people who love eating meat to take some meals where they don't eat any meat at all. And our idea is if we can do that and scale it, we're going to end up having an impact on global warming, among other things, because the carbon footprint of a meal with meat is enormous compared to the carbon footprint of a meal that has no meat. So that's what we're up to. 90% of our customers are non-vegetarians, even though there’s no meat on the menu. We want to sell to people that love eating meat, because that’s where we can have a lot of impact.

“Our mission is to help encourage people who love eating meat to take some meals where they don't eat any meat at all. And our idea is if we can do that and scale it, we're going to end up having an impact on global warming, among other things…We want to sell to people that love eating meat, because that’s where we can have a lot of impact.”

-Ayr Muir

There are a lot of other things we do that are really different. I think a lot of our success, like the reason those customers love Clover and look forward to it, is we source from farms and we source what's in season. And so the produce that we're sharing with people is really at its peak. And to do that means we have to have a menu that changes all the time. So we have a lot of tech we built and systems we built that let us gracefully make updates and changes to the menu on a day-to-day, week-to-week basis.

So what is the origin story of Clover Food Lab? You started as a food truck, right?

Yeah, I started Clover in 2008. I had been reading about food and the environment and I thought I could have a bigger impact on people eating every day. And it was a big ambitious project from day one, one I didn't think would work. So this is why we started with food trucks, just to test the idea, which was, you know, as it is now, trying to see if we can feed plant-based meals to people who otherwise love eating meat. So that that was sort of the idea. But there weren't any examples of that working in the world. I didn't have a lot of expectation we'd be able to make it work.

So we started our truck which actually had a ton of success. We started opening some more food trucks. At one point we were the largest food truck operator in the country. We only use food trucks now for catering, but it was a big part of our early growth. We were planning broader expansion, right before COVID. The timing of the outbreak was really tough for us. So we ended up, the past few years, we've been just refining the business within this market. And we still have the interest in expanding, but we will really need the capital to do that. And most people aren't really investing in restaurant companies right now. So that might be a little ways out still.

I loved your blog post about visiting your egg supplier’s farm to check on the chickens’ living conditions. As you know, in the food industry there’s a huge amount of “humane-washing” where allegedly humane meat, dairy, or eggs actually comes from truly horrendous, deeply unethical conditions. How do you make sure that your animal-sourced ingredients come from good places?

Yeah, I think ultimately, we would love to move to a place where there aren't any animal ingredients. But I think that's a little ways in the future. Since our start, we've used eggs and cheese and some dairy, modest use. And we still do. But we're actually about to make an adjustment in the next year where any item on the menu you can just ask for a vegan version, which will be fun. So we're making changes to make everything substitute that way, but in the meantime we do use eggs and other things. And I think that the climate impact’s pretty minor, from eggs, but if you’re concerned about humane issues around animals, it’s a bigger issue. The eggs that we source right now, we go to the farms and look at their conditions. I mean, there's no other way to really do this other than that. And if a supplier won't let you do that, that's like a nice clear answer. And we've dealt with that in the past too.

The chickens, it's not like a pastoral life. I mean, they're like, they're not in horrendous conditions, but you know, it's not fantastic conditions either. And, you know, the farms only keep them while they're productive layers, which doesn't last that long. So I mean, I think it's like as good as we could do at this stage, but I don't think it's ideal. I actually personally, I have chickens in my backyard. We have like a dozen chickens and we've had chickens for a while. I think it's a different thing eating eggs from those chickens than it is from any chickens from a farm. Even if a farmer's trying to, you know, do things well, it's just not quite the same.

But like I said, I think that what we have in place right now is as good as we could be doing. We don't use a whole lot of dairy, but we work with a cheese supplier called Grafton, which is in Vermont. They're a pretty amazing company. They've been doing really great things for years. We buy yogurt occasionally from a company called Sidehill. It's in Western Mass. And Sidehill is actually the only yogurt maker in Massachusetts that's fully integrated. So they have their own cows that they milk and then they make their yogurt with their own milk. And, you know, that's a situation I actually think—you know, I visited them a number of times and feel very good about it.

The difficulty is, when people start using animals for business, very quickly they start making trade offs that are not in the favor of the animals. So I think that you do have to be cautious. And really, there's nothing that's a substitute for just going yourself to visit and observe directly. But that's true for all food, by the way, with any supplier. When we buy coffee, we go and we look at what the roasting operation looks like. If we buy beer, we go and we look at the brewery. So I think that same principle carries through for other things too, because there's a lot of weird things people do.

“The difficulty is, when people start using animals for business, very quickly they start making trade offs that are not in the favor of the animals. So I think that you do have to be cautious. And really, there's nothing that's a substitute for just going yourself to visit and observe directly.”

-Ayr Muir

I’m a big fan of Beyond Meat and Impossible Meat, which are trying to replicate the exact flavor and texture of animal meat. You’ve gone a different direction, looking to highlight many foodstuffs that are naturally somewhat meat-like but still clearly their own thing, like mushrooms. Can you talk about that?

For me, if I buy Impossible, it’s expensive. That’s probably what’s limited these businesses. If you’re already vegan, maybe there's a reason to stay more, but if you don't have any problem with eating meat, why would you buy something more expensive? I think that's a difficult proposition for a lot of people.

And it may change, but it's going to be challenging because you know, forget about plant-based meat, look at oat milk, right? It’s crazy that water and oats is much more expensive than dairy, where you have to have a cow that’s milked. And the reason is there’s a lot of subsidies in our system that make that dairy milk as cheap as it is, and those same subsidies aren't hitting and supporting oat milk. I think, you know, it's the same thing when it comes to meat. There's a lot of government spending that beef benefits from that Impossible or Beyond don’t. Unless there’s a political shift, it’s going to be very, very difficult to get wide adoption.

You’ve said that you at Clover don’t brand yourselves as sustainable or vegetarian food, because that can turn some people off. Can you tell me more about that?

It’s always evolving. Most people don’t really want to be preached to. Our avenue has really been through taste, like getting people excited about flavor and taste. And that's usually our first foot forward. And most people that love Clover, that's their primary connection point. That's worked really well for us. We remain focused on that. We’re not coy about our environmental mission, we don’t try to hide it, but we don’t make it the first thing we talk to people about.

Food awareness and food knowledge is quite low. Somebody the other day told me, wow, your oat milk latte, it was a real life-changer. For that person, that was a wild thing for them, that they could have a latte with oat milk. For me, when we’re selling someone an oat milk latte, I think it’s a very normal, basic product, but for many customers, it’s an adventure for them. So I think we always have to just keep reminding ourselves, what little steps do we need to start out with?

Like with the tomato soup we make, it’s naturally vegan, it’s really creamy, it’s got carrots and tomatoes in it. That lets us bring in carrots, which we can buy about 10 months of the year from New England growers, which is awesome. We can bring those into the soup and it brings some of those dollars back to farmers and also improves the nutrient profile of the soup. Tomatoes, we're only buying regionally for a very short period of the year, but it makes something, tomato soup, that's very familiar, more nutrient dense, and also more beneficial to farmers in New England, but without making it too scary for people to approach it or try it.

How do you develop relationships with farmers? How does it go? Do you go to farming conventions and say, here's a really cool person, I want to buy whatever they're selling? Or do you say, we need a new produce supplier, let me go find who's doing it in a cool, sustainable way?

People come to us. That’s generally how it works. Clover’s got a good reputation, and farmers that like working with us tell their friends. Usually people come to us. It’s not much work on our part! That tends to be how it works.

Vegetarianism and veganism has this air of being modern, but there's also, you know, really rich plant-based, protein-rich cuisines from all over the world that are thousands of years old. Do you want to talk about some of the roots of your guys' theory of plant-based cuisine and what inspirations you draw from?

Most people in history, in most cultures, meat was rare and lightly used in cuisine, with very few exceptions. It’s a very modern idea-the average American eats 3.6 servings of meat a day. That’s totally new. It’s interesting, food is very cultural. You run up against a lot of cultural challenges. One is people, there’s been language created that associates protein with meat, and then associates meat with strength and virility and machismo. Which is kind of crazy, because if you eat a lot of red meat, it’s not great for fertility, and not great for long-term health. And many people, I would say probably most people in the US, think that protein is meat and meat is protein and they don't really think there is protein other places. Many people don't know that there's protein in beans, and then beyond that people don't know there's some protein in wheat and that there's some protein in broccoli.

I think that probably the number one nutritional concern for Americans today is “I’m afraid I might not be getting enough protein,” and then maybe right after this “I'm scared of carbohydrates” So, you know, those are very strong unfounded beliefs about nutrition that Americans have right now, which will make what we're doing very difficult and it's complicated to work through that. I think I don't have any great answers. And it's made it much, much harder to do what we're doing, because there's a lot of customers that are just like if they don't see meat in the meal, they don't think they're getting protein. It's very difficult to combat that belief.

Interesting. So could you give me an example of the Clover process of creating a new dish, from farm to finish?

Many, many examples. One is a fun one because it’s a little different. A lot of people thinking of local farms are thinking of cucumbers and things like that. But there’s a mill down in Plymouth where they’re milling corn, and they’re trying to work with farmers to grow heirloom varieties of corn they could mill, and find a way to sell the cornmeal. We did some menus, we ended up making Samp, a kind of traditional porridge.

We also made a Hasty Pudding, we made cheese grits for breakfast, we made a corn muffin, that we make with this Plymouth cornmeal. The corn muffin’s on our breakfast menu right now, it’s a beautiful corn muffin, the corn used is grown in Rhode Island and southern Massachusetts, it’s heirloom varieties of corn that wouldn’t be grown otherwise. And we’re directing customer dollars to that.

I think I’ve read that you’re related to famous conservationist John Muir. Is that at all important to you?

Just distantly related. John Muir did amazing things, so it’s very inspirational to me and many others. Yeah, I think it’s a nice reminder that people have been thinking about conservation and the preservation of natural spaces for a long time.

What question should I have asked that I didn’t ask?

A rapidly growing part of our business is meal kits. What we do is, we'll ship you a box that become a meal for your household. Usually it's dinner for people. Monday we have salads and what the salad is changes week to week based on what's in season, different farms. And Tuesday we'll have tacos, Wednesday we'll have soup, Thursday we'll have burgers, Friday we have pizza. So each day of the week this thing goes a different way and people subscribe to, on average, like three of these.

But it's been a lot of fun and I think that the most success has come from families with kids. You know, it saves people time and they can trust the food. It’s neat because the meals are awesome, people love it, and without knowing it they're eating a vegan meal one or more days of the week. Which is really fantastic. So it's been a fun way to see our mission extended, and it's something I hope to see continue to grow.

Ayr, thank you for joining us.

Thank you.

Wow! We don’t even eat meat 3.5 times a week although I grew up eating beef for every meal. We don’t eat beef and pork anymore. Eggs come from our own hens, who free range through the yard.

I still have my “Diet for a Small Planet” (from the 1970’s) as well lots of other vegetarian and Mediterranean cookbooks. You don’t need meat or factory eggs.

Great interview! With broadband delivery it is sometimes a "last mile" problem. With businesses like Clover I suspect it is a"first mile" problem: getting the

consumers through the door of tasting the products for the first time. After they taste how good the food is, you get devoted clientele. It's just that first step that's the biggest.