The Weekly Anthropocene Interviews: Annalee Newitz, Science & Fiction Author

Terraforming future planets, learning from ancient cities, living alongside animals, the impressiveness of naked mole-rats, and more.

Annalee Newitz is an acclaimed science fiction novelist1, nonfiction author2 and science journalist. Their third novel, which just came out in early 2023, is called The Terraformers, and received praise from The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, and The San Francisco Chronicle (as well as this newsletter’s review). Their latest nonfiction book, Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age, is a national bestseller and was praised in The New York Times, The San Francisco Chronicle, and The New Yorker.

They are currently a freelance science journalist, a contributing opinion writer at The New York Times, a columnist at New Scientist, and the co-host, with Charlie Jane Anders, of the Hugo Award-winning podcast Our Opinions Are Correct.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Mx. Newitz’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

Let’s start with The Terraformers, and your thoughts on planetary-scale ecosystem governance. What I love about that book is that it brings ecology into the realm of high science fiction. Like, there's a laser battle over diverting the course of a river. There are so many ideas that you share in your book, but one that I really want to talk about is your fascinating idea that the internet and the ecosystem will merge, as you beautifully imagined with Destry's powers. So, can you just tell me about this world, guided by the principles of the Environmental Rescue Team and taking place far in the future on a different planet? Can you just share some of the ideas that led to this creative universe?

The book is about a group of people who are terraforming another world. They are working for, or they’re owned by, an interstellar real estate corporate that wants to build a planet that looks like Pleistocene Earth, because that's very attractive for real estate buyers who are nostalgic for the Earth of many thousands of years before the book takes place. The main characters are part of a group called the Environmental Rescue Team, and their job is to be first-responders to emergencies and natural disasters, but also environmental engineers who keep ecosystems in balance. They’re kind of ancient order of engineers and first responders, and there are hints that it’s almost a spiritual order, if you could imagine a spirituality that’s kind of techno-animist. And they have an engineering handbook with a lot of guides to interacting with nature, and we get little excerpts from their handbook throughout the novel. and find out a little bit about the deep history of this group.

So they’re working on making this planet into a Pleistocene Earth ecosystem, and they’re encountering all kinds of problems that actual environmental engineers encounter, ranging from ecosystems that are out of balance to corporate interests coming in and messing around with land use and making life much harder for all the life-forms in the system. The book takes place over fifteen hundred years, because I wanted to have a big enough canvas to allow the reader to see ecosystem change. Ecosystem change is not very rapid, usually. Right now we’re living through a period of fast ecosystem change on Earth, but it’s still taking place on the order of centuries rather than minutes or month. So I created this big canvas, an intergenerational, multigenerational epic. We see different generations of people who are shepherding this planet and the different kinds of issues that they face. The inspiration for this really came from the work that I’ve done as a journalist covering environmental issues, covering deep time, looking back into geological time at previous mass extinctions, but also looking back in anthropological time at previous civilizations on Earth that have transformed into the world that we have today. If you have read any of my science journalism, the themes are going to sound familiar.

The thing that I really wanted and needed to do was kind of have a story that in some ways was a wish fulfillment. The main character, Destry, has this ability to interface with the ecosystem. The ecosystem on this planet is dusted with sensors that form these ad hoc networks that exchange data about the health of the ecosystem. Like they're measuring nitrogen levels and oxygen levels and acid in the soil and health of plants and you know, food web robustness. And she has these sensors on her hands where she can place her hands on to the earth and send her consciousness out into all of these sensors and feel the chemical reactions taking place, feel the metabolic pathways coursing through the system. It allows her to be a really good environmental engineer. But also this is definitely for me, a pandemic book where I threw a lot of stuff in because it gave me comfort, and it kind of fulfilled a wish that I have.

So Destry’s superpower of being able to physically feel what’s happening to the environment is kind of a dream. Also, because it’s set in the far future, there’s incredibly advanced genetic engineering. People aren’t like the people of today. There's Homo sapiens, of course, but there's also people who are moose, and naked mole-rats, and cats, who’ve been genetically engineered to be human-equivalent intelligences, but they’re in the body of a cat. So there's a cat who's an investigative journalist. I've always loved to write non-human characters, but also during the pandemic I just needed a story where I had a talking moose that has a romance with another moose. It was really comforting to me to imagine a world where human relationships are not centered. I was really sick of humans in a lot of ways. That was kind of how it came about. And like all my fiction, it started with me interviewing a lot of scientists.

Awesome! So that is amazing. If I hadn't read the book already, I would be desperate to read it now.

One thing that really stood out to me was the visual imagination and world-building of the story. There’s a scene where you have genetically modified intelligent earthworms playing a video game as honeybees. And that’s just in the background, that’s like in a version of the Star Wars cantina scene. That was so cool.

And the historical background details are also fascinating, like in the backstory something huge happened in Saskatchewan. The planet is named after Saskatchewan. There's all this legend in the Environmental Rescue Team handbook about Native American deities doing something in Saskatchewan. There was clearly some kind of huge transformative event that led to sort of Environmental Rescue Team type principles being adopted, the Food Revolutions, I think you called it. And now it’s been co-opted to be just lip service, just like every other would-be genuine social movement in history.

You’ve got this delightfully evil corporate character, Ronnie, who’s like “Oh, yes, we're totally focused on doing what’s best for the ecosystem.” And she's creating sentient beings to be sold as slaves. And that seemed really realistic to me, because that’s pretty much what happened with every major real-life religion. Christianity used to be a radical social movement, and then starting with at least Constantine, it’s been used to legitimize whatever the empire of the day was. I feel like a lot of other sci-fi works basically say that whatever the author’s favorite viewpoint is, the world will just become utopia once it’s widely accepted. But you're like, nope, there will still be bad people, even if the whole world is turned on to the importance of ecosystems. There will still be people doing horrible things and just saying that they follow these beliefs.

I think that’s a very perceptive reading of the book. One of my preoccupations in my work is this idea that of course we are going to change our relationship with nature. We're going to develop, hopefully, new civilizations, in a Star Trek-y way. But at the same time we're still going to be grappling with all kinds of problems. grappling with all kinds of problems. There's always going to be people who suffer from mental illness, some people where that mental illness takes the form of trying to harm and control other people in a coercive way. But I also think that there’s always going to be a problem with systemic injustice. It’s a constant struggle for people who are trying to create better relationships with nature and balanced relationships with each other, against whatever system is trying to give some minority of people a lot more power or resources than others. I don’t want to say this is human nature, because what the fuck is human nature. But I think it’s part of how our social relationships work right now.

Because I’m not a wizard, and I can't predict exactly how the future will unfold in 60,000 years, you know, I'm dealing with thinking through the problems that we're dealing with now on Earth. So I really wanted to show how it would work if we did have an alternate point of view. about how human beings fit into nature, which is definitely an Environmental Rescue Team point of view. And what I was imagining-you kind of alluded to the farm revolutions and these events that took place in Saskatchewan. What I was imagining is that the planet proceeded as we expect it will, which is that there will be sea level rise. There's going to be really catastrophic climate migrations and that food resources will dwindle, and there will be, you know, wars and famines.

Eventually what happens in my timeline that I was imagining is that groups like indigenous folks and land-back movements would actually be the people who kind of come to the forefront with the best solutions for these problems, and that all of these scattered tribal groups will eventually turn out to be the ones who can lead human civilization into a future where people are able to eat again and live in balance with habitats again. And there's a group of activists, most of whom are Cree, who are working with genetic engineers. And they figure out a way to build non-human animals so that they are able to communicate with humans, and so cows and moose and dogs and cats, and all of the animals that we have in and around our agriculture and our homes, are now no longer just being acted upon, but they can kind of come to the table and bargain with us over how we use the land. And in the book, they refer to this as the Great Bargain. This is the moment when humans are finally able to bargain in a way that is collaborative and equal with the natural world. If they’re wondering, how do we build cities so it doesn’t harm this moose habitat over here, they don't have to guess. They can just go ask the moose and the moose will say, actually, we’d really like it if you would, you know, build over there instead. And so that ushers in a new phase in human history, and also Earth history, where the environment is able to talk back.

And that was something that, again, is kind of a fantasy that I think that a lot of us have who are interested in environmental politics. What if we didn't have to just try to convince other human beings that trees have rights or rivers need to be shepherded, or that non-human animals have the ability to feel pain and shouldn't be abused? What if all of those things could just speak for themselves and tell us to shut the hell up and listen? And so that's what has happened in in the distant past in this novel. And then, of course, as you said, there are still many social structures like corporations which push back on that, you know, and try to figure out how they can extract resources and can still use other living beings as uncompensated labor, while still remaining in balance with nature somehow.

So at the time that the book takes place. there's been these Farm Revolutions, the Great Bargain has happened, there are many non-human animals and robots who are working alongside humans, but there's also corporations who are trying to own land and privatize a lot of the resources that would have belonged to all these other people. So there's a kind of a counter revolution going on, and that's what my characters are stuck in. The middle of this counter revolution, and they're having to push back again and reassert their rights.

That is really fascinating. And thank you so much for expanding on the back story of the Great Bargain, because you kind of piece it together from the book, but I don't know if it's ever like explicitly set out like you said it here.

One thing I really love about your work, from your books to your short stories like When Robot and Crow Saved East St. Louis and The Almond Pirates, is the focus you put on animals. I find that science fiction ignores animals all too often. There’s the classic trope “are we alone in the universe,” and I’m like, are you kidding me? By the mirror test alone, there’s like twenty other sentient species on earth right now, apes and cetaceans and corvids. Your work really pays attention to the real moral weight and significance of animals in a way that relatively few people do.

You're welcome. And of course, because I love non-human animals. I mean, humans are fine, too. I think that animals do show up in science fiction and fantasy a lot, but one of the things that I always want to push back against is this, I want to call it stereotyping. What you'll see is you'll have a science fiction story where there's, like, tiger people, and they're all really aggressive and bitey and fighting all the time, or they'll be rabbit people who are really swift and scared, or robots who are cold and calculating. And I try to make my non-human animal characters and my robot characters just as diverse as humans in terms of their personalities, and what they're interested in and like. Toward the end of The Terraformers. There's a fleet of sentient trains who are performing public transit for the planet, and they form their own collective, and they bargain collectively, and they figure out the best way to do routes between cities and things like that. And I was like, well, what if they don't want to be trains? There's all these creatures being built as trains, but maybe some of them don't want to be public transit. And so we meet some of the trains who've like gone into other kinds of thing. One of them designs video games and some of them do biotech development. And so they don't all have to be the thing that they're supposed to be based on their body type or based on their ancient evolutionary history.

You know, you see it a lot in Star Trek and Star Wars, where it's like, oh, it's the person who has the personality of whatever they look like. Each planet is like a small village following a particular cult. Every Klingon is honor-bound and warlike and all that. There’s no queer artist Klingon. I mean, maybe there is! I hope we meet that person one day.

Could you share your thoughts on wildlife-friendly cities (a major theme of my newsletter)? You’ve written about "the moose in the swimming pool" as an urban future.

Sure. that's a great question. When I was working on my book Four Lost Cities, which is about ancient cities, that grew out of previous work I had done about cities as ecosystems. And I'm really interested in thinking about urbanism as just a form of ecosystem and thinking about how cities and undeveloped areas interact with each other, and the porous border between what we call wilderness and what we call urban or suburban. Because there is no real boundary. We like to pretend, oh, we can put up a wall. But then lichen grows on the wall, and birds fly over the wall, and animals burrow into the wall. I’m really interested in breaking down the distinction between urban and not-urban, and thinking about how wildlife flows between human these human habitats and these habitats that are not dominated by people, the very few habitats that are left on the planet that are not dominated by humans.

So I'm always drawn to stories about how wildlife comes into cities. But also I love stories about how cities and towns try to are increasingly trying to adapt to the wildlife. that comes through. You can see examples all the time, like in Davis [California], they’ve built a little tunnel for frogs to go under the road so that they don't get squished when they go on their migration, their little frog migration. There's examples of this in Australia. There’s a giant crab migration on Christmas Island, and they've now figured out ways to divert the crabs so that they don't just get squashed on the road.

And one of the Utopian images I've seen a couple of times in relation to San Francisco, the city where I live, is the idea of at some point in the future opening up the main street that goes downtown. It's called Market Street, not unlike many other cities which have a Market street. San Francisco's Market Street cuts all the way through downtown, and then it continues down south. It was built on top of a river, and so this was like the center of a lot of like natural life and a lot of a gathering place for animals that weren't just homo sapiens.

And that river is still there. I mean, it's been, you know, boxed in by development. But what if we opened that up again? And had a kind of migration corridor through the middle of the city. I think that's just a super cool idea. And also it makes sense. It's better for the wildlife. It's better for the city, because you don't want wildlife coming into the city and like splatting on your windows, or causing trouble of various kinds.

So there's there's been a lot of discussion, I think, among people who are interested in environmental futures about, how do you build a city so that elk could migrate through it or fish could migrate through it, or whatever?

So I like that idea. I like the idea of acknowledging the porous boundary of cities and the wilderness, and actually inviting the wilderness in and making a place for it, and not treating it like an invader. I think that also will allow us to have a more balanced ecosystem within cities, because often in cities like you get this explosion of pigeons and corvids. Which for me…I love corvids. I'm not as crazy about pigeons. That's a personal issue that I need to work on.

Rosemary Mosco has a great book on overcoming “pigeon trauma” and learning to love pigeons.

Yeah, that's so awesome. I love her work so much. She's just fantastic.

But anyway, I think that like if we were to make more space for a wider range of species in our cities, you would have predators of pigeons helping you out with that. And we're starting to see that happen here in the Bay Area, because peregrine falcons are that have bounced back from near extinction, and they love to eat pigeons. There's a peregrine falcon family that I follow on a webcam, and they are just helping out. And they’ve been given a permanent home on the clock tower at UC Berkeley, where they return every year to have babies and eat more pigeons. I love that idea.

The Terraformers definitely deals with that, but also in Four Lost Cities, I tried to talk about how animal life flowed in and out of these cities, and how people tried to adapt to it, but then sometimes tried to keep it out as well, and that that was kind of the origin of cities in some ways, was about trying to hold certain kinds of wildlife at bay. so that that's a perhaps one of the origin stories of why we think of cities as being separate from wilderness.

Yes, can we talk more about your amazing book Four Lost Cities and the lessons we can learn from Pompeii, Angkor, Cahokia, and Çatalhöyük in the age of climate change? You’ve written extensively about previously unrecognized models of civilization (often overlooked because they didn't fit into European archaeologists' paradigm) from tropical cave art to wampum belts.

David Graeber’s last book, which he co-authored with David Wengrow, who's an archaeologist, is called The Dawn of Everything, which really deals with a lot of the parts of human history that I’m not able to touch on in my book, although I do talk about some of the same places. I read some essays that became that book, and that helped inspire my perspective. The Davids’ thesis, in that book, is that we have focused really narrowly on one extremely specific definition of civilization, and one very specific place on Earth where we think that that took place, which just so happens to be the West. And it just so happens to be this narrow band of civilization that has focused on trade and resource extraction and economic development. And to our detriment, we've kind of ignored anything that didn't look like that and described it as being Dark Ages, or primitive, or nonexistent.

And so I chose the four cities in this book which are on four different continents, because I wanted to show that cities and the civilizations that support them can take a whole bunch of different forms. And those forms don’t go away, they just transform. In the popular conception of ancient cities and ancient civilizations, we have this model of the rise and fall of a of a civilization. We think that civilizations have like a life and a death, and once they die, that's it, they're gone. And that isn't how civilization works. Civilizations transform.

Even with a city like Angkor, which was the largest city on Earth at its height, with close to a million people living there, over a period of several hundred years it shrank down to, basically, a village-sized population on the order of hundreds of people. Archaeologists for a long time said, okay, that meant that that civilization failed. It fell. It was over. But what actually happens, of course, is that when a city is abandoned it's not like all of its culture and ideas wink out of existence because the people who lived there all go move too other places, they migrate away, but they take the ideas with them. I wanted to explore the fact that not only are there these many different models of civilization, but they’re not gone, they’re still with us today. We’re still living in the stream of history that they added to.

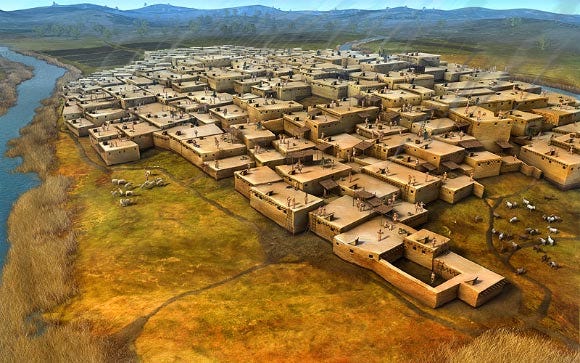

I start with one city that is now called Çatalhöyük, a Neolithic city that was as its peak about nine thousand years ago. That's when it was like really rocking. They were having great parties, and lots of people were excited about it. And at that time, a super rockin’ awesome city was about five thousand people. That would have been huge, because most people either lived in small nomadic groups or in villages of about a hundred people. So if you'd spent your whole life hanging out with like a hundred people, and you came to a place with 5,000 people, you'd be like holy crap. This is just enormous.

And it’s kind of cusp-y, it has many characteristics of modern cities, but it also has characteristics of villages. and so sometimes so archaeologists argue like, is it? They sometimes say it’s a “mega-village” or “proto-city.” I think it was the city of its time. Cities are relative. It was the biggest settlement that would have existed for thousands of kilometers around, it would have functioned as a city does today.

And it was built in a very different way than most modern cities are. People mostly had houses that were roughly the same size. They built so that the sidewalks of the city were on the roofs of the houses, so the houses were all connected to each other, kind of like in pueblo style, or like a honeycomb. So all of them shared walls, and then you entered houses through the roof. To Western eyes, that looks really alien. That's not how we expect cities to look. But it made a lot of sense for the people who lived there at that time. It allowed you to have workshops and social life on your roof when the weather was nice, and then you could kind of go downstairs into your cozy warm home when it's cooler, and that's where you have your hearth. And that's where you do a lot of work, probably in the colder months. Or during the rainy season.

One of the really interesting things about Çatalhöyük is that it lasted for a really long time. Like people were living there at a pretty large population size for about a thousand years. Pretty badass, for a city! San Francisco’s only been around for like 150 years. So they're doing really great and we got to see a lot of social transformations that are visible.

When you do archeology as we excavate the site, you can start to see things like chemical evidence that people start cooking with milk, for example, which is a really big deal. It's a big transformation. So in this civilization, people also start using fired pottery, which is a huge technological advance, enormous. People always talk about like the Bronze Age like that's a big deal, but fired pottery transformed our diet because it meant that you could cook in pots at high heat, you could boil things in pots. And before that people would heat stuff up, or they'd like roast it on the fire, but they couldn't make a stew, at least not the way we make stew, so it really changed it. Like a labor saving device, basically.

So we see those changes. We also see evidence of cultural practices where people are interacting with wilderness through art and through the way they build their houses. That kind of suggests that people were trying to work out, like, what was their relationship with nature now that they're living in a sedentary way, they're not travelling like nomads anymore. They're living in the city, and it's a city with a lot of history. Most of the people who lived in it would have lived there when it had when it was hundreds of years old, right? So they're living in this ancient settlement, and what is their relationship to nature at that point? They're living in a thing that was entirely built by humans. And we see representations of animals, and we see them doing things like drawing animals as being larger than humans, but sometimes as smaller than humans. And a lot of anthropologists think that that's humans rethinking their relationship with the natural world as animals kind of shrink down. But also they'll do things like when they build their homes. they build them with animal bones in the walls, as if they're kind of building a barrier between human habitation and the wilderness, and there's this wall where animals are kept at bay.

And again, of course, this is open to interpretation. We don't really know what they thought. they didn't leave any writing behind. They left a lot of art behind, but we don't know what they were like. Maybe they they were just like, Wow! That was a great dinner. I'll keep that bone in the wall, because that was tasty. So it might turn out that we're we're wrong about these interpretations, but it seems like there, there was a concerted effort to think about how much of nature do we bring into our human habitat, and how much do we keep out. What do these walls mean about who we are?

And eventually, of course, the city is abandoned. People stop living there for many hundreds of years. It's a cemetery and kind of a holy place, even into like the Roman era. We see some Roman burials there. And then the city kind of crumbles and becomes just this hill. And everybody in the area around where the cities are kind of knew about the fact that they've been there. If you were farming in the area like you'd often find like figurines, or pieces of brick, or whatever from the old city. So it wasn't lost. People claimed it was a lost city, but it was everyone knew it was there. It was just that they weren't really sure what it was or what its significance was.

So what we do know is that when people abandon the city, there’s a change. In that area of the Levant, central Turkey and going up into the north and south from there, people went back to village life. So there's this phase that's about a thousand years long, where people retreat from these mega sites and go back to these small villages and and nomadic existence. Some archaeologists say it's almost as if people in that area rejected urbanism and were like, “Actually, that sucked.”

And then in Mesopotamia we see this incredible resurgence of urbanism, where, instead of having houses that are mostly the same size, and everybody is kind of sharing the same roof essentially, you get things like these ziggurats and pyramids, and palaces, and crazy walled enclosures to keep the riffraff out of the fancy city. So these are civilizations that show physical signs of hierarchy. Usually, when archaeologists look at at a city and they see a giant palace. they feel like that represents a hierarchical culture, because at least one small group has a lot more property than most of the other groups.

So there's a big question mark there, like, what happened? Why did people go from these kind of egalitarian structures to these much more hierarchical structures? And also that's around the time that we see the emergence of commerce and taxation. And again, that’s something that David Graber has written a lot about.

We see other cities in the Americas, like Cahokia, which was a going concern about a thousand years ago, along the Mississippi in Southern Illinois, where they do have these monumental structures, they do have pyramids, but they don't seem to have commerce. There's no evidence for commerce. There's no evidence for even wide scale trade. There's evidence for people like swapping trinkets, but not like trading like a giant amount of grain for a bunch of coins. They they don't have coins. And so that's an example of, this is a civilization that's engaging in the same practices of monument building, of interaction between cities that are quite distant. But they're not taxing their citizens, and they're not using money.

So it forces you to question of the received wisdom about the development of civilization. Like, maybe there's no reason why we had to develop money. Maybe there's no reason why we had to associate great monuments with people who have more resources. I love having that kind of comparative lens to kind of say, well, there's this one path that civilization takes. There's another path that we can take. There's many more that we don't even know about.

During the Neolithic period, which is thousands of years long, all kinds of social experiments were taking place, and the reason why I think that's incredibly useful to know is that it reminds us that we could go in lots of different directions as civilizations, too. We're not stuck being in the systems that we're in. Like, we could totally have a completely different state system. We could have a non-capitalist system. and it would be fine, and we would still have cool shit. And that's great, like I love looking at a civilization where it's like packed with cool shit, like art, music, writing, people hanging out and partying.

So you’ve written about the wonder that is naked mole-rats. I knew that they were unusual, that they were the only fully eusocial mammals. But when I read your article, I was blown away. They almost seem like an animal from a video game where someone just decided this is their favorite species and decided to give them all these powers. Could you tell us about why naked mole-rats are so awesome?

I mean, there’s lots and lots of really interesting things about naked mole-rats. They are the only mammal that we know of that forms a eusocial organism like a beehive or an ant colony. All that means is just that in a naked mole-rat colony, there's only one member that is giving birth. So there's one female who actually has offspring, and then all of the other members of the community care for them collectively. That's what bees do, they have one fertile female. But that's laying eggs. So it's a very unusual set up. Usually mammals do not have a breeding class of individuals. Every every individual that's capable of breeding does so. That makes them quite different.

They're also quite long lived. They are cancer resistant. Nobody knows why. They're being heavily studied for that reason. They have a really weird diet. They live underground in tunnels. They're hairless and mostly blind, and they interact through feel and smell. And they only eat one thing. It's just this giant tuber, and once they find one of these tubers, that's the source not only of their sustenance, but also their water. They don't really drink water. They just get water from this tuber. Kind of like how peregrine falcons never drank water, peregrine falcons are hydrated by blood.

So naked mole-rats are being studied right now by a lot of scientists because they're interested in their ability to fend off cancer and to repair mutations in their DNA But they're really hard, I think, to breed in captivity. So there's a lot of research that needs to be done that just hasn't been done yet on them. And I don't know if anyone's trying to make them into a model organism, but I suspect that they are, and once they do that, then we'll know a lot more about them.

I'm trying to think if there's any other groovy shit I know about them. The breeding female uses hormones to help all of the members of the colony recognize each other and communicate with each other, and to work together. Kind of like ants, there's emergent properties in their behavior. It's not like there's one naked mole-rat who's giving everybody else orders, but they are connected to each other through this hormone, and that helps them determine what kinds of stuff they need to do. Like, who should be taking care of the babies? Who should be going to get more tuber? Who should be digging more tunnels?

And it does seem that when members of the colony get far enough away from the breeding female that they lose that hormonal connection, and they start engaging in other kinds of behaviors that are not colony behaviors anymore. So again, that's similar to ants, ants coat their bodies with hydrocarbons, kind of like pheromones, that allow them to recognize each other and smell each other and figure out what they need to be doing in the colonies. They're like mammals who kind of act like social insects who live a really long time. Also, they're not very charismatic looking. I was just talking to a journalist who does a great podcast called What the Duck?, and they said that naked mole-rats look like old men in the shower at the gym who’ve just smelled something bad.

They do!

They are not very pretty. But they are strong, and interesting. There are several [sentient] naked mole-rats in The Terraformers who have a lot of opinions about things.

I don't know if you have plans to do this, but the biology seems like a set up for a sci-fi story in that universe. You could have a naked mole-rat that leaves the colony and loses the hormone smell and starts developing new behaviors, and maybe having a fundamental philosophical shift in how they relate to the universe as an individual.

Yeah, and it could be a good allegory for what happens when people, you know, leave their corporate jobs or leave the church and are like, what do they do? Because, you know, humans have like mobile phones, social cues, stories, clothing and a bunch of stuff that says people like this behave this way, people like that behave that way. Memes and stories are kind of like our hormone smell. And so if you get away from those memes, what happens? I guess we’re in the middle of a giant social experiment about that. We’re going to see what happens.

Thank you for writing and thinking about this stuff and doing what you do. Is there anything else you'd like to discuss?

I mean, I think we've actually talked about a lot of my obsessions. that I'm excited about. I just finished a new nonfiction book that I'm hoping is coming out next year, and it's about the history of psychological warfare in the United States. So I've kind of gone back to my social science roots and and done a book that deals with that, not physics or geology.

One of the things I found while researching this book and kind of what the book is about is that a lot of the psychological warfare products that are developed by the military to persuade and coerce people have made their way into culture wars. It's very similar to what's happened with in the United States where we've had legislation that has allowed military weapons to be acquired by police forces at low cost or no cost. And we see this kind of transfer of military technology into domestic spaces. The same exact thing has happened with psychological warfare.

And so a lot of the culture wars that we're deeply in embedded in right now are actually the result of this kind of weapons transfer and it's been really interesting to to see that and realize it. And now that I know, it's easy when I see culture wars bubbling up to see the origin of a lot of the rhetoric and a lot of the tactics that have come out of about 200 years of psychological war in the United States.

I'm excited for people to read that book. It's called Stories are Weapons. I'm almost done revising it. I'm going to hand it in at the end of the month, and hopefully it'll go into production soon.

Awesome! Thank you so much.

And thank you. I mean, you've obviously really super thoughtfully engaged with my work. I really appreciate that, I really appreciate your nuanced response to it. And that's been really a pleasure.

Their second novel The Future of Another Timeline, received starred reviews from Publisher’s Weekly, Kirkus, Library Journal, and Booklist. Their first novel, Autonomous, won the Lambda Literary Award, and was nominated for the Nebula and Locus Awards. Their short story “When Robot and Crow Saved East St. Louis” was winner of the 2019 Sturgeon Award.

They’re also the author of Scatter, Adapt and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction.

Best interview ever! And that's saying alot! I purchased the Terraformers a while back and it was the best, most original, take on corporate planetary engineering I've read. A classic and highly recommended! Just an outstanding novel.