The Weekly Anthropocene Interviews: Dr. Rhys Lemoine, Megafauna Rewilding Scientist

Earth's amazing wild history - and future!

Dr. Rhys Lemoine is a Canadian ecologist currently working at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. His research focuses on the immense potential to regenerate rich, vibrant ecosystems around the world through megafauna rewilding. Dr. Lemoine has also published an excellent series of rewilding articles on his LinkedIn.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Dr. Lemoine’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

This interview is syndicated by both The Weekly Anthropocene and Your Daily Dose of Climate Hope.

Why is megafauna rewilding important? Could you give an overview of the role played by now-absent megafauna in many major Earth ecosystems, when and how they went extinct across most of the world, and why we should bring them back? What are we missing, essentially?

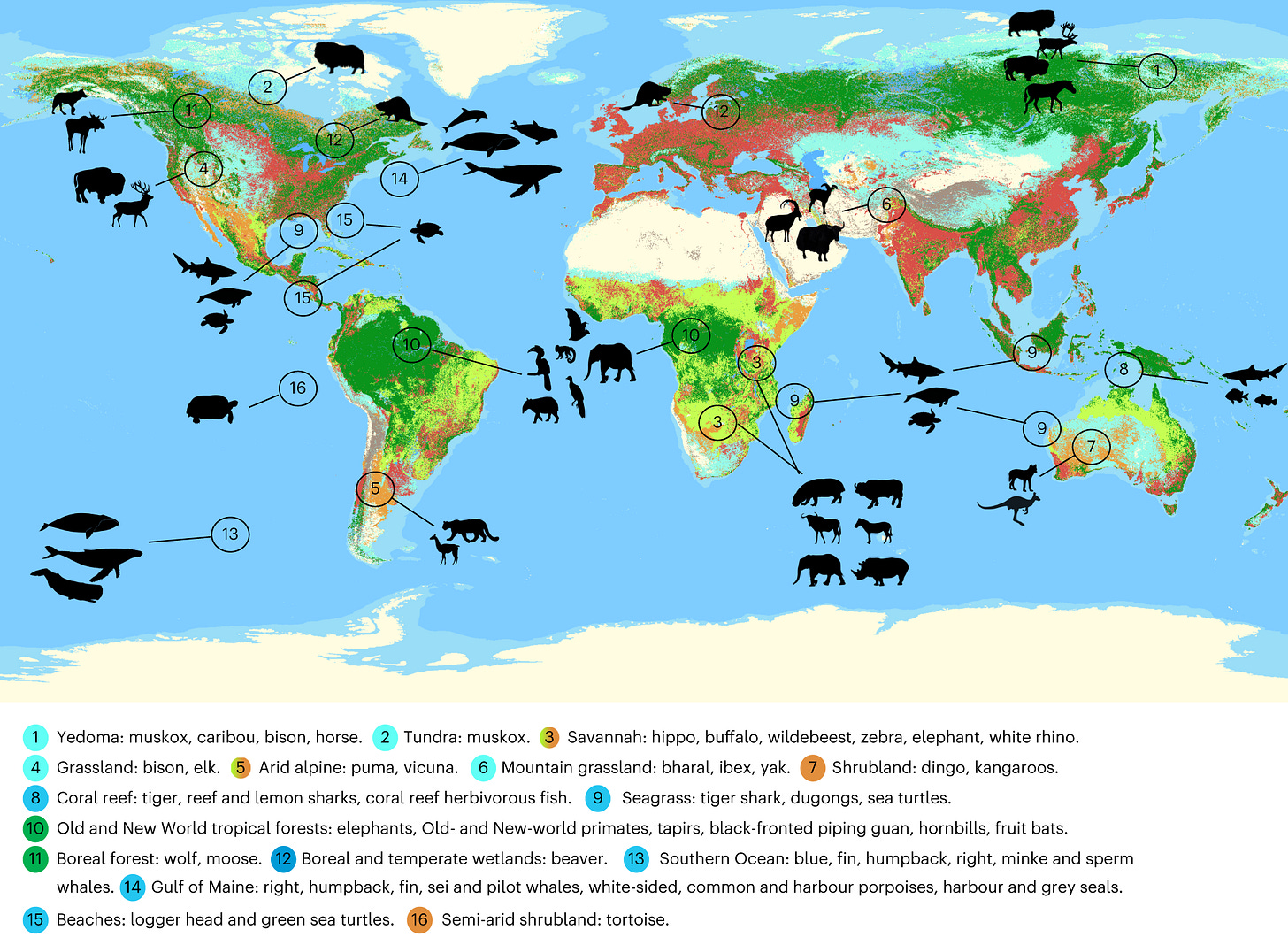

Today we think of large animals as being almost exclusively found in Africa and South Asia. Elephants, rhinos, hippos, all of the animals that can weigh over a thousand kilograms on average live in those areas.

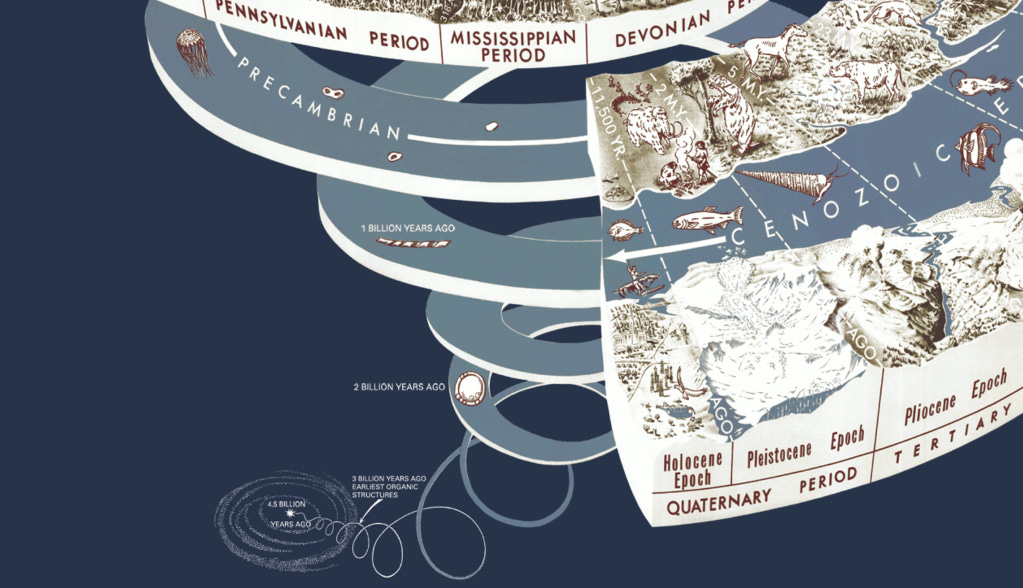

But of course, that wasn't always the case, right? It used to be every continent had large animals of that size. And from a geological perspective, it’s only extremely recently that that has ceased to be the case. When I say recently, I mean between 5,000 and 50,000 years, depending on the location you're talking about.

I’m very much on the side — and I think the evidence is increasingly on the side — that this is an effect of modern humans moving out of the places where hominins evolved into places where there was no history of hominins. And then through over-hunting, other forms of exploitation, and habitat modification, causing extinctions amongst most of these large animals to varying degrees in different places.

Now, that's important because invariably the largest species tend to be some of the most ecologically important and to have perhaps the least redundancy. So you get the situation where ecosystems that evolved with many and diverse large mammals or other forms of vertebrate suddenly have far fewer, far smaller, or none.

You know, with varying levels of extremity. In Eurasia and North America, we still have bison and things like that, though much depleted. But in Australia, the largest thing is a red kangaroo, unless you're counting crocodiles.

And for the timescale on this, this is happening around the beginning of the Holocene epoch, around 11,700 years ago, and even before that. This is happening before serious agricultural revolutions. Stone Age technology was enough for humans to drive a lot of these species extinct.

Yes, absolutely.

What you described so far, I think people might easily confuse it with modern trophy hunting and poaching and stuff, but no, this is a long time ago. All of recorded history, more or less, has been since we’ve wiped out all these megafauna.

Yeah, with some amount of overlap. The last mammoths were around the time the Epic of Gilgamesh first popped up. But yeah, that's generally true, we are talking about pre-agriculture. There's a good argument to be made that agriculture sort of came in response to the fact that megafauna hunting became less viable as a result of extinctions.

Ooh, that's interesting! I hadn't heard that one before. Could you elaborate?

Sure. Let’s back up a few steps.

Okay, so humans are generally considered to be apex predators, but in one particular aspect, we're not particularly good at it, which is that only about 30% of our calories can come from protein. The limitations of our liver and other organs make it so that we can't eat more than that, or at least we can't effectively process more than that. And fiber, we can maybe only get 5% of. But that means the entirety of the 60 to 70% remainder has to be met with either fat or carbohydrates.

Now, pre-agriculture, fat was far more available than carbohydrates. Some research that's coming out now has found, as established by Ben-Dor and Barkai, that the most efficient way to get enough fat out of a primarily hunter-gatherer diet is to hunt the largest and most reproductively aged megafauna available in the system. Often specifically females as well. So what happens with that is that you can then make a living off of entirely megafauna, but as a result, it eventually leads to local extinction of megafauna.

The theory is that this started even before our species, Homo sapiens, existed, with species like Homo erectus. The idea is that Homo erectus was predominantly a megafauna hunter, that Homo erectus was exploiting things like rhinoceroses and elephants, in large amounts. So what happens is that as Homo erectus starts to have this sort of effect on the largest megafauna, then in response, in order to meet caloric requirements, smaller and smaller animals have to be hunted.

But, perhaps counterintuitively, smaller animals require a greater level of technology to hunt effectively than larger animals!

Like snares and traps and stuff as opposed to running up and throwing a spear at the big obvious thing.

Exactly. Some of the earliest extinctions that are attributable to hominins are large tortoises.

Oh yeah, that's really easy.

Yeah, so we actually see some extinctions in Africa and maybe South Asia that are attributable to Homo erectus, and it's always in the most large, slow-moving kind of species for this reason, including large tortoises. The theory is that this level of exploitation and subsequent adaptation towards smaller game actually is what drove the evolution of Homo erectus and similar forms into Homo sapiens as the level of intelligence required to make sufficiently complex tools increased.

Fascinating.

Then once Homo sapiens migrated out of the paleotropics — so tropical Asia, tropical Africa — megafauna hunting then became a viable strategy again, but with an even greater level of technology. [For example, it’s currently thought that Homo sapiens was the first hominid species to invent the bow and arrow, making them even better hunters than Homo erectus].

Following that, there would then have been another crash, even bigger this time, as megafauna were hunted to extinction. Leaving humans where they started, but now with the greater brain capacity to then figure out agriculture, which can support more people than hunter gathering because it produces carbohydrates. And as soon as megafauna are no longer in the scene, fat hunting becomes no longer a viable strategy.

That's absolutely fascinating.

Zooming forward to today, to me and you it seems obvious we should bring megafauna back because they're cool and awesome. But just from a utilitarian perspective, what benefits do we get with megafauna rewilding today? Everything from carbon sequestration to landscape management to all sorts of stuff.

I know we've lost huge high-productivity ecosystems like the mammoth steppe, there’s entire latitudes of the planet where we don't have big carbon cycling wildlife anymore. I want to get into species by species later, but just broadly, what are we missing?

Well, you covered a lot of it there, right? But yeah, a big one is nutrient cycling. And carbon sequestration. Like you said, large herbivores specifically cycle a lot of biomass back into the system and often into the soil where it's less likely to be lost through things like fire. And fire is another one, because herbivores reduce total [plant] biomass and increase heterogeneity and increase coverage of things like grass and herbs compared to shrubs and trees. Generally, they reduce fire intensity and severity in so doing.

In several studies, you can see the break in sporomelia, which is a genus of fungi associated with animal dung, you can kind of see where it peters off and then levels of charcoal in the system kind of go up as a result. Both are associated with an increase in people, because a reduction in megafauna is also associated with an increase in people.

So in the age we have now, with a hotter climate, we would really like a lot more carbon to be cycled into soil and we would really like a reduction in fire intensity. And also, incidentally, we have a global agricultural system that means most people are not desperate enough to need to hunt anything large and slow moving for food. It seems like we could really use some megafauna!

That gets us into rewilding, and the big case study, obviously, is Europe. There’s been a huge rewilding movement in Europe that’s led to a gigantic increase in many species’ populations, including megafauna like European bison. Can you give me an overview of what that's looked like in Europe, on a very broad level?

Sure. Generally, where it started was with the work of a Dutch ecologist named Frans Vera. who came up with the wood-pasture hypothesis. [Check out the Wikipedia page for the wood-pasture hypothesis].

And what Frans Vera hypothesized was that, in layman's terms, “Isn't it weird that most of the rare biodiversity that we have in Europe is associated with open and mixed habitats, not closed-canopy forest?” The idea being that it doesn't make sense that all of Europe would have been closed canopy forest or other sort of shade loving trees in the absence of people. Because then why would we have all of these things that are clearly not adapted to those conditions?

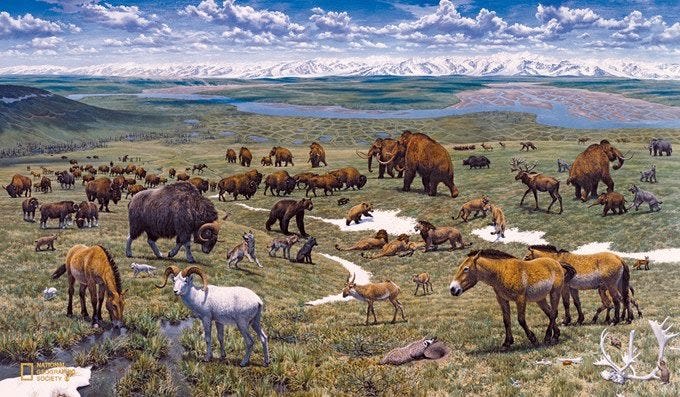

The hypothesis was that, well, those conditions must have been created by the original sort of wild herbivores that would have been normal in Europe. And he was mostly talking about Holocene stuff, so horses, aurochs, bison, these sorts of things. It's been debated whether or not he was correct in thinking that this works in the Holocene context, or whether these things are themselves remnants of the Pleistocene state, where you also had elephants and rhinoceroses. These things would also later have been encouraged by Neolithic farming and stuff like that.

The basic premise led to a lot of what are now called rewilding projects, which had all sorts of other names applied to them at the time. Famously in the Netherlands, with the Oostvaardersplassen, experimenting with high densities of cattle. horses, and red deer, and seeing what sort of effects they could have on environments where it was not considered desirable to have a lot of regeneration of trees and shrubs. Specifically, in this case, wetlands that were proving to be a very good habitat for geese and other wetland birds.

And so it was experimented with. Okay, could these species effectively stop forest encroachment? And for all the other things that people have said about it, that's certainly true. They can. They did.

So that's led to all sorts of other kinds of experiments in Europe, such that this has kind of become standard practice in a lot of places. It's actually a lot cheaper to have large herbivores in an area than it is to actively manage it for the same effect with machinery or tools or whatever like that. Ultimately, these kind of areas usually have more biodiversity value than if you simply let it turn into another closed canopy forest.

Yeah, that's one of the things that's really counterintuitive for people. We're used to comparing forests to an entirely human-dominated landscape, like when forest is cut down in Indonesia for palm oil or in Brazil for cattle ranches. So we in the environmental community are often like, “Forest good. Why would we want anything other than forest?”

And forests are great, obviously! But when you have that mosaic effect, that heterogeneity, like you said, in a natural context where animals are, physically breaking open the soil and doing bison wallows and all the stuff they do, you do get more biodiversity than just a forest without large animals in it.

That's a thing that I think people are surprised by. Because for a long time, in a low megafauna context, in a lot of places the choice has been forest or nothing, right? The choice has been either forest or a totally human dominated landscape. But now if we put some large animals back, we can have something even better, a mosaic with forest and also bits of grassland and wetland and other cool stuff that's formed and shaped by animal activities.

Yeah. Heterogeneity is very important. I think a lot of the time, not only do we over-prioritize forest in conservation and in restoration discussions, sometimes it leads to us promoting forests in places that shouldn't even be forest. Especially in dry areas, where ecosystems that might, both historically with human usage and prehistorically with megafauna usage, have been more like open woodland or savanna, are allowed to grow into these extremely flammable low biodiversity plantations, essentially. We don't always use that word to describe them, but it is kind of what's happened.

Let’s talk about pachyderms, the elephant family. You’ve written about the widespread potential for the reintroduction of pachyderms in North America, Europe, and elsewhere. I was lucky enough to see wild elephants last year for the first time in my life, Asian elephants in India, and you can really visibly see that mosaic-forming effect. They leave a corridor when they walk through the forest.

The world used to have pachyderms almost everywhere, and now we associate them with the paleotropics only, tropical Asia and Africa, like you said. Could you summarize the role that they played in North America and Europe and across the world and how important that was?

Okay, so first some context. Every continent except Australia and Antarctica had elephants of some kind. Now, whether or not we would call them elephants proper is sort of a taxonomic issue, but proboscidians in general, right?

You would have had not only your still-living elephants in Africa and Asia, but also other species of elephants, even in those areas.

Like in Africa and South Asia, you had Paleoloxodon species, which were even larger than living species and coexisted with them. They’re generally called straight-tusked elephants, which also lived in Europe and East Asia. [Here’s Dr. Lemoine’s in-depth post on straight-tusked elephants].

Then in tropical Asia, you had the Stegodon, which were elephant-like, but had these sort of pillar-like tusks that kind of touched together in the middle to create almost one super-tusk. Both palaeoloxodons and stegodons produced dwarf varieties on islands, the former in the Mediterranean and the latter in Indonesia.

Then, of course, in northern Eurasia, you had woolly mammoths and steppe mammoths. Towards the end, they're kind of hard to tell apart. Both had at different times moved into North America, with steppe mammoths having developed into Columbian mammoths there, which spread as far south as Mexico. They were maybe slowly displacing the last of what are called the gomphotheres, which were a more primitive family of elephants or elephant relatives that were still established in much of Central and South America, groups like Cuvieronius and Notiomastodon. And then, of course, you had the true mastodons, which were still very widespread in North America at this time.

Check out Dr. Lemoine’s article on historic ecosystem engineers in Alaska and the Yukon, published on rewilding site The Extinctions.

So pretty much almost everywhere had something like an elephant, often more than one! And this would have had an enormous impact on the environment, just like the removal of elephants from protected areas does today. They can have huge effects on things like vegetation regrowth, fire, heterogeneity, et cetera. Not to mention nutrient cycling and carbon sequestration!

Effectively, the past removal of these creatures from places like the Americas and Eurasia is functionally no different, only that it happened a slightly longer amount of time ago. We're in many ways still seeing the consequences of that.

So it seems like there's a pretty strong ecological case to potentially reintroduce existing elephant species or even de-extincted elephant species to the Americas and Eurasia, in places where people would very much not think of elephants. The elephant family is, in a very real sense, native to Italy and Iowa.

And we see that in the landscape! Like coppicing, the traditional European method of renewable wood harvesting, that started as an adaptation to elephants, trees evolved to be able to grow back branches after big chunks were broken off by elephants.

What are your thoughts on the historic ecological relationships like this, of currently extant species, like white spruce and magpies, with extinct megafauna? I personally have always found this particularly evocative, like seeing megafaunal "ghosts" still around in the landscape. To anthropomorphize a bit,the ecosystems of many developed countries today are kind of “waiting for elephants.” There’s a lot of stuff there that evolved to live with elephants. [See the Wikipedia page for “evolutionary anachronism.”]

Sure! The specific relation to elephants is more obvious in some places than others. In a lot of places, there’s still fruits that have seeds too large to be dispersed by any living herbivores in the area! South America in particular is a classic example.

Which fruits?

A lot of the ones that have been domesticated, for example squashes.

Yeah, that's an elephant-sized food. A tapir’s not swallowing that.

Avocados are thought to have been dispersed by giant ground sloths. You can kind of tell, their seeds are pretty big! That's actually quite common in fruits that were later domesticated, including some that would recently have been dispersed by living elephants. Like mangoes, that were domesticated in Southeast Asia and are still a favorite of elephants there.

That’s common because dispersal by large mammals is actually a pretty good dispersal strategy — if there are large mammals to disperse them. It's only once that group completely disappears that they become sort of refugee species that are considerably less viable. Assuming that they're not later domesticated by humans, which was actually quite a common thing for a lot of them.

Tell me more!

You're in the eastern U.S., right? I'm from southern Ontario, originally. There are actually quite a lot of temperate eastern North American examples that are thought to have been originally megafauna-dispersed. Osage orange is a big one, pawpaw, squashes. Several species of legume, like honey locust and Kentucky coffeetree. These all have traits that suggest they were not effectively dispersed at all by any living large animals or smaller mammals. Some maybe are occasionally dispersed by smaller mammals, but less effectively. Persimmon is another big one, and wild apples.

Even marcescence, which is when trees keep their dead leaves hanging on the branch in the winter instead of shedding them. That helps protect twigs from being grazed by large herbivores.

You’ve written about the relationship of elephants and magpies. Could you tell me about that?

There's some speculation that magpies may have themselves been adapted to megafauna-driven landscapes, because they're still very widely associated with livestock and with grazing lawns or short lawns created by people. They actually show a lot of traits similar to an African corvid called the piapiac, a bird that is primarily associated with large animals because they flush insects. Oxpeckers and other birds like magpies and piapiacs will eat ticks off of large animals.

Historically, in North America, magpies were largely associated with bison herds for a similar reason. Much like European magpies, they later made the switch to livestock. We see actually a lot of biodiversity that is now associated with livestock that was previously likely associated with megafauna. This is also true of plants as well! Mesquite in North America is well-loved and well dispersed by horses and cattle, generally not a favorite of many smaller fauna, or less effectively dispersed by them.

In those regions of the American West, mesquite roots go what, like 50 feet down? That's because they evolved to at least have a chance of surviving being pulled up by the strong trunk of an elephant, right? Elephants are sort of “meant” to eat mesquite. That's what they evolved to resist, which is why they're so tough to get rid of today.

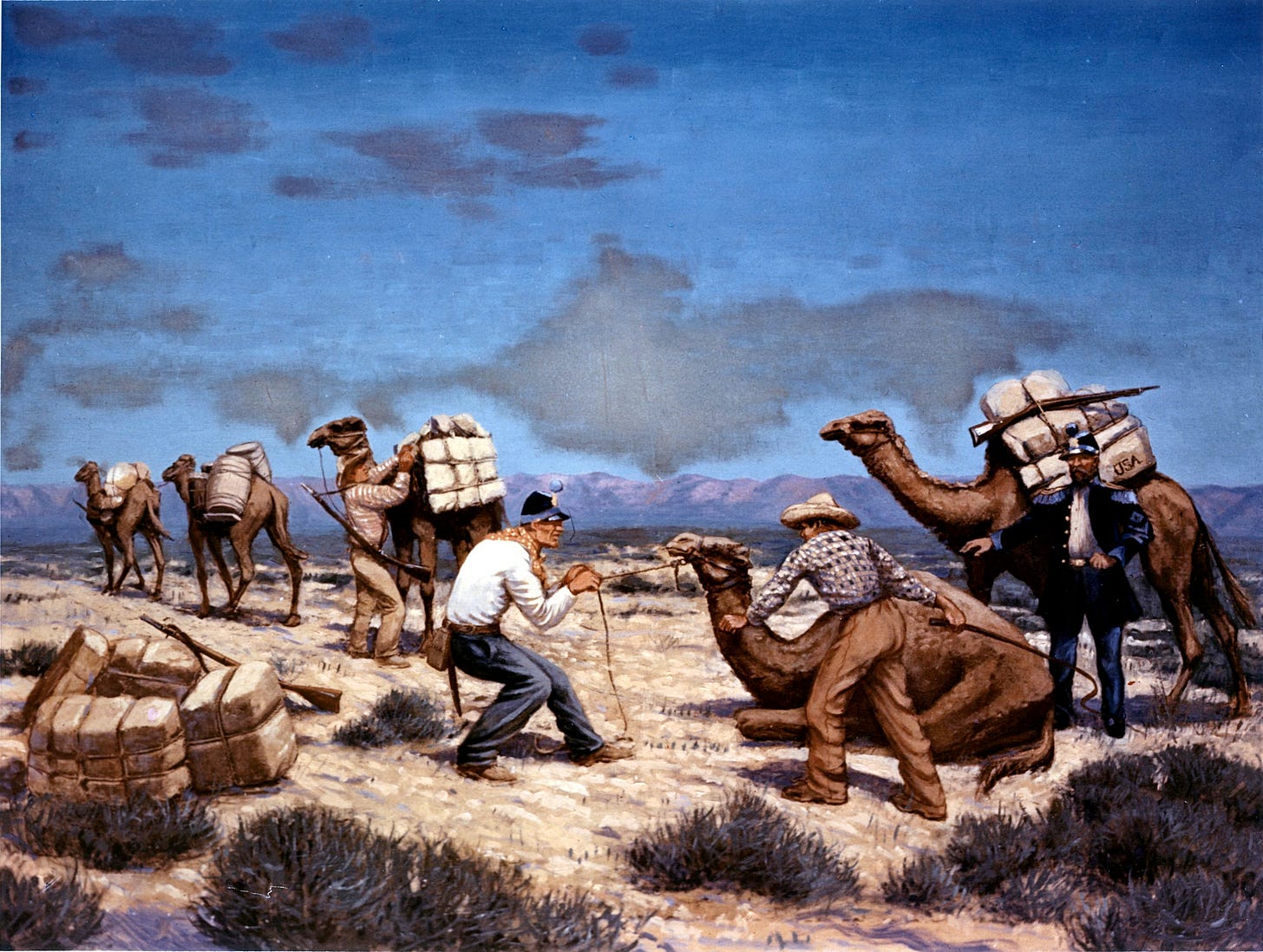

Sure. Another classic example is in the 1800s, there was a brief experiment by the American government, shortly after the Mexican-American War, to explore large parts of the desert territory what is now New Mexico and Arizona that had recently come under American control. It was very difficult to do so with mules or horses, so there was a brief experiment to import camels. It was briefly very successful! It was stopped because the Civil War diverted attention and funding.

But in that brief period where they were experimenting with camels, it was found that they ate a lot of American desert plants that were not popular with other herbivores. Mesquite being a big one, but also sagebrush and creosote. And a lot of these sort of things that can actually be a huge over-shrubification problem in the American Southwest today.

Because camels are another one of those species that was also in North America before humans showed up there. There's that classic thought experiment, “where do camels belong,” right? They evolved in North America, disposed over Beringia to Eurasia where they got domesticated…

…and now they’re most commonly found in Australia! It's a good question, right? Both camels and horses evolved in North America and were there until, depending who you ask, 5,000 to 10,000 years ago.

We're sort of having an informal, unexpected wilding with the massive takeoff of wild boar descendants, feral hogs, in the United States. One out of the box option there would be to reintroduce a major predator known to preferentially prey on pigs. What are your thoughts on the potential to rewild jaguars in the United States?

Jaguars were once naturally present across a huge chunk of North America. as well as a lot of their current range now.

A separate thought, what's interesting about pigs is that a lot of their explosion isn't so much to do with a lack of predation, but with a huge access to anthropogenic food. Pigs normally are very limited by the fact that they have not very complex stomachs and have to live off high-quality, high-carbohydrate foods. But as soon as you introduce potato farming or garbage dumps or any of these sorts of things, suddenly that limiter can go away pretty quickly.

What has been noticed in some parts of South America is that where pigs are super-abundant in association with human settlement, they are a favorite prey of jaguars. Which makes sense, because they are similar to a lot of things that jaguars already eat, like peccaries, capybaras, just that size.

I learned from your article that jaguars once ranged as far north as Pennsylvania. Right now we've got a couple individual males coming across the Mexican border, but what’s the long-term habitat available? Would climate change expand their range? What do you think the actual potential is for jaguars in the United States within the next hundred years?

Well, it's hard to say. In glacial times, they ranged as far north as Oregon or Washington in the west and Pennsylvania in the east. But they generally didn't fill out a lot of the middle area, suggesting maybe they weren't really present in the Great Plains area or in the Rockies. That may simply be because they’re an ambush predator not really associated with open grasslands. Or that a lot of the prey was found more in the forested areas. They were probably eating beavers and giant beavers and tapir calves and giant capybaras, which were also present in the Southeast and West. Maybe some calves of some larger things, and deer.

It seems like their range kind of forked, so that they went up both the coasts but then didn't go up the middle. But even historically, they were found in southern desert regions and riverine habitats of Texas and Arizona and California. There's some evidence to suggest that they were driven to extinction there and then later came back up, maybe as a result of the huge sudden crash in human population following the introduction of things like smallpox. Which is actually maybe true of a lot of things that had become very abundant in between the original arrival of people from Spain in the south and the later arrival of British people in the east.

Shifting around the world, you’ve written that monkeys and primates generally are another group of species that until recently had a much bigger range than people think. Could you discuss the potential for monkey and great ape rewilding?

One of the ones I wrote about specifically was the Barbary macaque, which is still found in northwestern Africa and the Atlas Mountains.

And Gibraltar, right?

Yeah, although it's introduced there. But prehistorically, that same species, Macaca sylvana, was found across almost the entirety of Europe, at least during warm periods, and during cold periods across most of the Mediterranean. It's kind of unclear why they don't anymore, because in previous glacials, they simply retracted to the south of the Mediterranean, then expanded back. Monkeys are themselves important in a lot of seed dispersal and other habitat functions, and it's kind of interesting to imagine them as part of European nature today.

Macaque extinctions are attributed elsewhere as well. Macaques survive in Japan, but prehistorically it looks like the same species, the Japanese macaque, was maybe also found in Korea but isn't anymore. And of course there were native monkeys in the Caribbean which are now extinct, but island extinctions are kind of par for the course, they happen on every island.

As for apes, orangutans are the most obvious one, because they're the only living ape with an extensive fossil record. Currently, we associate them with Borneo and Sumatra, but the fossils suggest they were also naturally present on mainland Southeast Asia and in Java. Given how threatened all three living species of orangutan are today, it could be quite practical to reintroduce populations of them to protected areas outside of what we consider to be their normal range, which may in fact be sort of a relict range driven by past human activity.

Yeah! That’s another mega-trend, right? For surviving large animals, we often think, “Well, where we're seeing them, that's where they must want to live.” But no. Often that's just the inaccessible habitat where they managed to survive because we killed them all in the parts near human settlement.

Sometimes it doesn't even have anything to do with how good the habitat is. Sometimes the places they survive aren't even ideal habitat. It's just that they were less accessible or for whatever other reason had less hunting. Like, orangutans are often most populous in high-elevation areas. The same is true for tree kangaroos and koalas in Australia, even though that doesn't actually seem to be any sort of habitat limitation. When hunting of any of these species ceases, we often see that they start moving into the lowlands again. It's just that those high-elevation areas were the least accessible to people and thus afforded the most protection.

We think of giant tortoises nowadays as something super exotic, in the Galápagos and maybe a couple other places, but where else in the world used to have giant tortoises?

Pretty much everywhere!

Tell me more!

It’s honestly one of the best examples of the history of human-caused extinctions that you can give, because it almost exactly follows the pattern of human evolution and migration. In the early Pleistocene, there were giant tortoises in Eastern and Southern Africa but then they generally seem to have disappeared following the evolution of Homo habilis and erectus. Then in South Asia and Southern Europe you had Megalochelys and Titanochelon and Solitudo. They also seem to disappear following the arrival of hominins. With some exceptions, usually on islands that didn't have humans till later like Sicily or Timor, both of which held on to their tortoises approximately until human arrival.

In Australia, you didn't have tortoises, but you had meiolaniids, which were convergent with tortoises, but a much more basal group of turtles. They kind of had an ankylosaur kind of look to them. They had horns and spiky tails.

I hadn't heard of those guys before!

They were found in the tropical parts of Australia and also on several islands around there. Fiji, New Caledonia, Vanuatu. And their extinction is also very well-timed with human arrival, with the last populations of those having gone extinct following human arrival there.

In the Americas you had Hesperotestudo, which in the warmer parts of North America holds on until the end of the late Pleistocene when humans show up. And in South America you had continental forms of tortoises extremely similar to Galápagos tortoises, that again go extinct once humans show up there.

Tortoises are then only hanging on on islands, which also sequentially go extinct once humans arrive on those islands. The aforementioned examples, but also the entirety of the Caribbean, essentially, had Chelonoidis tortoises very similar to Galápagos tortoises. Historically, there were also tortoises in Madagascar, very similar and in fact ancestral to the Aldabra and Seychelles tortoises. And in the Mascarenes, Mauritius, Reunion, and Rodrigues, you had Cylindraspis tortoises, which were the result of an extremely old evolutionarily distinctive group of tortoises that have been isolated there for millions and millions of years.

But every time people show up to an island with tortoises, with the exception of the very purposefully protected Aldabra and Galápagos tortoises which people had to interfere to protect, tortoises go extinct anytime people show up. Or even pre-people, even hominids. It's one of the most glaring examples of the history of human-caused extinction that there is. The only exceptions are two places that were discovered, A, very recently, and B, where people interceded to protect the native tortoises. And in both cases, there were still extinctions. Because not every Galápagos tortoise subspecies survives, and Aldabra tortoises were completely wiped out from the Seychelles and then reintroduced from Aldabra.

But there has been huge success in rewilding Aldabra tortoises, right? We didn't lose all the giant tortoises! This is like if we still had giant ground sloths living on some island somewhere and we could bring them back. This is a big classic group of megafauna that we almost totally lost but didn't.

So today, where do you think we should put Galápagos tortoises and Aldabra tortoises? Where do you think, ecologically, it would make sense to reintroduce those species, the giant tortoises that we still have?

Well, it's already pretty well underway with a lot of Indian Ocean projects where Aldabra tortoises have been introduced! First reintroduced to the Seychelles from Aldabra, and then following that they've been experimentally introduced to Mauritius and Rodrigues as ecological substitutes for the not very closely related but ecologically similar Cylindraspis tortoises. More recently, there's a trial site in northwestern Madagascar.

Yes!

Yes, where Aldabra tortoises are being used as a ecological substitute for the two members of the same genus, which existed there until Madagascar's colonization around 1200 or whatever it was. It was weirdly recent, humans’ arrival in Madagascar.

Madagascar’s right up there with Greenland and New Zealand as one of the last landmasses on Earth that humans visited.

There were two large tortoises there that were related to the Aldabra tortoise. And one of them was probably ancestral to it, or at least close to it. Closer to the Aldabra tortoises than to the other Madagascan tortoise. So that's being trialed.

As for Galápagos tortoises, it's been proposed for years but nothing's yet happened, to experiment with introducing them to several Caribbean islands.

Ooh, that’d be great!

Because there were other members of Chelonoidis that were closely related to Galápagos tortoises that lived in the Bahamas and Cuba and Hispaniola and a lot of these sorts of places.

And tortoises in the Galápagos are so important for the conservation of dry habitats and browsing of prickly pear and things, the management of which is actually a conservation concern in a lot of Caribbean dry forests. It's been talked about for a while that tortoise rewilding would be a very low risk experiment to try. because tortoises are famously easy to remove.

Yeah, like every time. Even with big “swing for the fences” things like mammoth de-extinction. People are always like “I've seen Jurassic Park, what if it gets out of control?” Come on, we drove all these species extinct with Stone Age technology! It’s easy. They are not a threat.

There's all sorts of problems with the Jurassic Park comparison that I'm sure you already know.

A friend of mine, Ben Novak, who’s working to bring back the passenger pigeon, actually made a t-shirt subverting the Jurassic Park comparison, with a Jurassic Park-style illustrated passenger pigeon and the phrase “Conservation finds a way!”

So I'm sure you saw the news, Colossal Biosciences had a good funding round and now claims they will bring back the woolly mammoth [or at least an Asian elephant embryo gene-edited with CRISPR to express woolly mammoth genes originating from frozen mammoth tissue found in Siberia] in six years.

What do you think of the potential near future de-extinction of the woolly mammoth, thylacine, and passenger pigeon? And what other species beyond them would you like to be de-extincted? I think that could be a really good thing. It's at least worth pursuing.

I think it's good to be realistic about what's actually possible with that. Keep in mind, when we say we're bringing back the woolly mammoth, what we mean is we're putting a few woolly mammoth genes in an Asian elephant. Hopefully that will be able to fill the ecological role. And I'm all for that, generally!

I think sometimes people hear we're bringing back the woolly mammoth and think, “Well, we could bring back anything.” No, there are some limitations.

Because DNA degrades over time. You can’t bring back dinosaurs.

No. And honestly, even with DNA, we have to be able to modify something that still exists. We couldn't directly clone a mammoth because we don't have any living nuclei or, or living cells that could just be transplanted into a, an elephant host. Because we only have DNA, we kind of have to use that to modify a cell line that already exists. It's just very convenient that mammoths were basically the same elephants, right? I mean, they're closer to Asian elephants than Asian elephants are to African elephants. If we allow elephants to live in colder environments, that is essentially filling the ecological role of a mammoth.

But you couldn't do the same thing to a tree sloth to make it a ground sloth, you know? That would be a fundamentally different and greater undertaking. That's just where our current technology is at right. We also don't currently have the ability to clone birds, which is why Colossal is kind of pushing to get that technology to the point where we can. I'm sure that would also be of interest to the chicken industry

But yeah, that's just sort of generally a limitation. All I'm saying is that, while I think the de-extinction technology is very interesting, it does have a lot of limitations that people may not be aware of.

In fact, in the form it exists now, it essentially just is a conservation tool, right?

Right!

I mean, it can be used to increase the genetic diversity of living endangered species or to improve the ecological capacity. There was a paper, I believe sponsored by Colossal or somehow involved with it, but they came out in a good recognized journal, that estimated extremely conservatively that Alaska's North Slope could hold about 0.13 mammoths per square kilometer.

And that was extremely conservative. A lot of the weights they used were overestimates, and they didn't take into account that productivity rises when you reintroduce herbivores, and thus carrying capacity. So 0.13 at the minimum, extremely conservative. If you assume that to be the case for the entirety of the Arctic tundra, that's 1.5 million mammoths. That would mean Alaska's North Slope alone could support almost as many Asian elephants with slight mammoth-gene modification as there are Asian elephants now. [The paper estimates that Alaska’s North Slope today could support approximately 72,000 mammoths].

Yeah! And that could help save the world from melting permafrost, right? That could have huge ecological effects.

It's certainly a mediatory possibility. It's one of those things that only works if we're actually doing other stuff to address climate change. Basically how that works is that large herbivores, not just mammoths but also horses and bison and things like that, excavate snow, which allows cold air to come into contact with the permafrost, thus cooling it several degrees. That is a very useful thing, and one that we should be working on scaling even without mammoths. But mammoth de-extinction is a very interesting avenue and I do hope it has some success — and not just because I personally really want to see one!

I do think that de-extinction technology in its current form is essentially just a conservation tool because the only thing we can use it for is to improve the range and diversity of living cell lines. [E.g. by adding mammoth genes to closely related living Asian elephant cell lines]. We quite simply do not have the ability to create a living genome from scratch. [Yet.]

Even thylacines are a much bigger undertaking than mammoths, even though they went extinct more recently, because the amount of genetic changes to make a dunnart into a thylacine is exponentially more than an elephant into a mammoth.

With passenger pigeons, the closest living species is band-tailed pigeons, and they're pretty close too. The potential is just incredible.

What are some more out of the box ideas for rewilding? And/or some kind of genetic cell line enrichment slash de-extinction. I've brought up a lot of the rewilding ideas I'm aware of, but your articles often bring up ideas I’ve never thought of, like cassowaries or macaws or sirenians as rewilding candidates. What other rewilding options do you see, as an expert on megafauna, that we haven't discussed so far?

I mean, a lot of the cases are going to be maybe less interesting than that. It would be great if we could get more American bison and more European bison projects.

I think South America has a lot of potential, and there's been people who talked about this long before me. Mauro Galetti first proposed this idea that elephants and other larger animals could be rewilded on the Brazilian savanna. The reason behind that being that they are so amazingly fire prone, so flammable, and flammability in protected areas is actually a huge, huge concern. Ironically, in an attempt to protect a lot of these protected areas, cattle grazing and horse grazing was ceased within the confines of those parks, which of course meant that there was more biomass and everything was even more flammable.

Check out Dr. Lemoine’s in-depth article on rewilding potential for South America.

A lot of the most biodiverse ecoregions on Earth are naturally disturbed, are places where trophic impacts, so fire and herbivory, are crucial. We have this idea that if we just leave it alone, it will behave naturally, but that doesn't work.

Not only following the extinction of megafauna, but also following the breakdown of traditional management by indigenous peoples. Originally you had large megafauna remove a lot of the excess biomass, create heterogeneity, and reduce fuel loads. Then the megafauna are gone, but the people who live here understand that it's important to keep things open and diverse and to prevent larger fires, so they do burns and management of remaining megafauna in such a way that biomass still seems low. And then we have us now doing nothing. Having no megafauna and just sort of waiting for things to pile up and then explode.

Like in California.

I mean, if you look at La Brea, it was once like the Serengeti! That's Los Angeles now. It was a big open dry savanna filled with camels and horses and bison. Now it's a forest and it's going to explode. The same thing for the whole boreal region in Canada. Maybe this is too dry to be a forest. Maybe the idea of dry forest is itself kind of flawed, and we need to manage it more like open woodland or savannaor something like that.

Mauro Galletti proposed something like that for the Brazilian savanna, with elephants specifically coming up a lot. He was particularly interested in, this was not set up for this purpose, but there's an elephant sanctuary in Brazil that has former circus elephants and stuff in a sort of retirement. There's been a couple of people who were interested in seeing what their effects would be on, on fire proneness and nutrient cycling and all these things.

I think if there's going to be experiments with [seriously rewilding] elephants anywhere, it's going to be one of three places.

It's going to be in the Arctic following partial de-extinction efforts,

Or it's going to be South America in either Brazil or Argentina.

Or it's going to be Europe, where people have been talking about experiments with elephants in fenced reserves for actually a very long time.

Just to see what happens, right? It's an easy enough thing. There's been talk of setting up an elephant sanctuary in Europe as well for a long time.

I think regardless of how far we go with these kinds of ideas, it's important to have them and to experiment with them. Because it's unavoidable that almost every ecosystem on Earth evolved in the presence of not only huge diversity, but enormous densities. of megafauna.

The estimates for the Siberian mammoth steppe that have been published are something like one mammoth per square kilometer! Plus seven horses, five bison, fifteen reindeer — the reindeer were probably migratory, so spread that out a bit. But still, these are densities similar to or higher than what we consider normal for the African savanna.

People have no idea. Even where you have megafauna today, it's a percentage of a percentage of what you should have. You should have an uncomfortably high amount.\ And then people start saying, oh, no, you're not supposed to, because there's no predators. But people have a fundamental misunderstanding of what predation does. Predation does not reduce total herbivore biomass in a system with all herbivores present. What it does is shift it away from the smaller species towards the larger species. Predation does nothing to elephants. Often it has a much smaller effect on buffalo than it does on things like antelope and zebra. And that's part of what makes these things work, right? They will have a higher biomass of the largest herbivores, but these are also the most generalist herbivores, which are going to have the most general wide-ranging effects on the ecosystem without specifically removing some specific species of plant.

I see.

Whereas, if deer are allowed to become overabundant, that can happen because they're selective grazers.

Like the Kaibab case.

Yeah. We kind of expect deer to be controlled by predators, but we really don't expect it of a lot of larger herbivores. And in fact, that's a very important part of how natural herbivore systems work, is that some herbivores have sort of escaped predation. Certainly lions don't control [i.e. hunt and eat] rhinos, right? It's just not a thing.

And some things that are more in the middle, like buffalo, it’s extremely contextual and has something to do with how migratory is this system. Because migration also means that some herbivores escape predation entirely, including some smaller ones. That's why there's millions upon millions of wildebeest in East Africa, which is a migratory system due to precipitation differences. But in South Africa, where precipitation is much less spatially inconsistent, wildebeest are usually much less common because they never really escape areas where they would be subject to predation.

Fascinating.

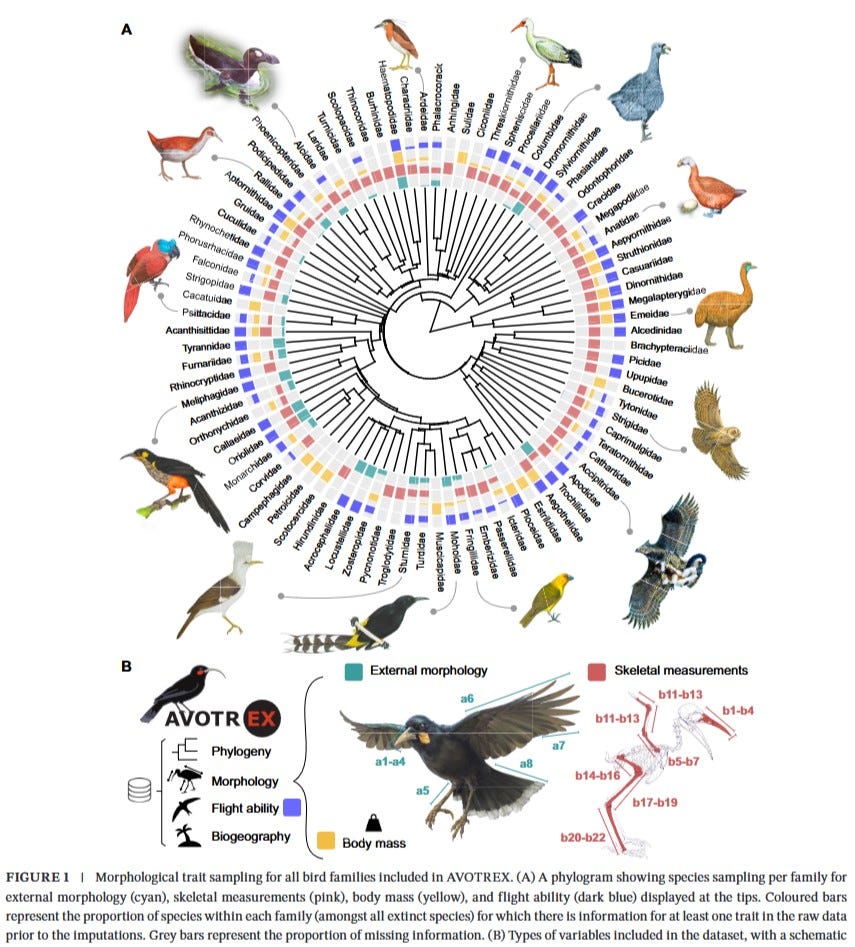

To jump around again, could you tell me about your AVOTREX database? That seems like a really interesting project.

I should point out that I'm just a co-author. I am using it very heavily for something I'm working on now. The data set itself was created by Ferran Sayol, who worked in the same lab that I'm working in now. He was first author on the paper for that. I joined it later because I had some information about continental bird extinctions that were later added. It's a very important data set, and one kind of similar to some previous ones that I and other people had worked on for mammals, like the PHYLACINE Project and things like that. The idea behind it was just to assemble traits for as many modern and recently extinct birds as possible in order to have that data set be available to people looking to do macroecological studies.

This is primarily data on their physical form. This is not genetic data, right? This is data about what we know based on fossil records of the physical form of these birds.

Exactly. For all species, basically, it's just a collection of morphological measurements and a few other traits for... for living and extinct birds. I'm working on a project right now that has to do with co-evolution, and co-extinction. Basically, the idea is, there were bird extinctions in the Lake Quaternary. Considerably fewer than for large mammals. But those birds that did go extinct are largely associated with megafauna in some way. And so what we're kind of doing is looking to measure the effect of different traits on bird extinction. Just trying to determine statistically what traits make animals more or less likely to go extinct

Awesome!

I've also interviewed and visited the lab of a gentleman in Maine working to bring back the chestnut in America. That would also facilitate much higher animal biomass, and potentially the wood-pasture system.

Sure, I don't know the guy personally, but I'm familiar with the association.

I'm really hopeful that even as we face these unprecedented challenges with climate change, with the combination of humans who are less reliant on subsistence hunting than ever before, more efficient agriculture, maybe a demographic global demographic peak, and we've already had a peak in global farmland acreage…I'm hoping that we can right this 10,000-year-old wrong, and even in the middle of all the other challenges we're facing, bring back these megafauna to the world. We are seeing that in some places, and I'm hoping we can see it more. So thank you for doing the work you do!

A lot of the interesting stuff that's also being done now is trying to objectively and in a non-biased way look at the effects of already introduced megafauna as well. I have a friend and colleague, Eric Lundgren, who does a lot more of this kind of work. I would encourage you to look into it as well. He comes at it less from this sort of prehistoric angle and more from the idea that invasiveness is itself kind of a myth.

It is! I wrote a series of articles about that last summer, citing you. Very controversial!

Yeah, I read it!

What Dr. Lundgren does is, he's done a lot of interesting work to empirically show that least with large mammals, you can't use their nativeness to predict what their effects are going to be. There's no measurable difference really between what native herbivores do and what introduced herbivores do that has anything to do with whether or not they're native or introduced. Where this comes up a lot is Australia.

The whole concept of invasive species, it's not scientific, almost, in the sense that it’s not Popper-falsifiable, right? You can't actually consistently see the signal of native versus invasive in the data, at least for non-disease species on continents.

In fact, what you find is exactly the same thing I was talking about earlier, which is that the best predictor of whether herbivores are going to have a positive or negative effect on biodiversity is how selective they are. And that has nothing to do with nativeness. There's plants that are at risk of extinction in Florida because of white-tailed deer, and it's the same thing that happens where deer are introduced, right? It's because they're selective feeders, they can selectively browse those most palatable plants, and that can actually lead to the exclusion of those plants.

It's the same thing with feral goats or a lot of other similar sort of small browsers. Large generalist grazers, like buffalo, are almost universally going to have a positive effect on biodiversity. It doesn't really matter where they are. Really what it shows is only that plants are adapted to high densities of large generalist herbivores and not to high densities of small selective herbivores.

This is absolutely fascinating.

And with global warming, very soon, if not already, no species anywhere on Earth is going to be living in the same place with the same conditions it evolved in, right? The world has changed fundamentally. We're past 1.5 degrees Celsius. Nothing is the same as it was.

So, I think we should be much more proactive and less precautionary about introducing and reintroducing megafauna. Like, “We're not 100% sure what this animal will do, but we're pretty sure that broadly speaking, it's better to have it here than not.” Let's put tortoises in the Caribbean islands. Let's put elephants in a park in Italy. Let's do these things!

And there's been a little bit of movement on this. I don't know if you saw, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service changed their interpretation of Section 10(j) of the Endangered Species Act, which means they're now allowed to do conservation introductions outside of a species’ native range. And they’ve already done one!

Sure! The nice thing about big things is that it's easy to experiment and easy to reverse the experiment if it has failed. Tortoises, elephants, easy to spot and remove. Maybe not easy to move, but easy to remove in general.

I think a lot of work has to be done with trying to, from an unbiased perspective, evaluate what's actually going on with mammals or other large animals that have already been introduced. And whether it's better to have the wrong megafauna than no megafauna.

I'm rooting for the camels in Australia and the hippos in Colombia, because it looks like they might actually be decent ecological substitutes, like hippos for toxodons, right? It looks like they might actually be having a really net positive impact in those ecosystems.

Yeah. I think it's also important to let go of the idea that something has to be a one-for-one substitute. Camels maybe aren't especially similar to anything that lived in Australia, certainly not taxonomically, but in terms of what their measurable effects on vegetation are, it's better to have them than to not have them. What happens if we don't have camels? We'll have more fires, and we'll have less browsing of introduced shrubs.

These are systems that are inherently dynamic, whether we let them be or not. Anywhere with intermediate precipitation like that, it needs consumers [of lots of plant biomass] otherwise it will be consumed [by fire]. It’s inevitable. We can try to choose to do it in a responsible way, through grazing and browsing or prescribed burning or ideally both in a lot of cases. I think it's a thing that we're going to see change a lot in the near future out of necessity.

Thank you so much. And also, I'm excited! I would love to see mammoths on Alaska's North Slope. I would love to see giant tortoises on Caribbean islands. I would love to see all of this. I'd love to see this this wilder world.

It's almost like a secular environmentalist version of original sin or something, in which the original ecological sin of the rise of our sentient species was driving this mass wave of megafauna extinctions. And now we can finally make that right again.

Sure, and it’s kind of like a dispelling of this idea that humans' negative effects on the environment are exclusively a recent thing, right? It's not like environmental destruction started 200 years ago. It's been happening for thousands and thousands of years, that we just forget.

Yeah! And the systems that we have now make it possible to do better on some of the problems we caused thousands and thousands of years ago.

Exactly! And we're uniquely able to address some of these problems now because we have our needs met in other ways, right? A huge thing that's gotten the rewilding movement in Europe going is that globalization has led to widespread land abandonment, because it's no longer profitable to farm in a lot of the warmer, drier parts of Europe.

Also just technological advancement! Fertilizer and stuff means you can get more food on less land. Yield per acre keeps going up.

Yeah, fertilizer, genetically engineered crops, whatever you want to do. Honestly, improving the yield of land does more to free land from agriculture than anything else!

What happens is you have large areas of Spain and Greece and Italy that people are leaving, because it’s not profitable to farm there anymore. All the children leave and go to the city. So there's just sort of these aging populations living in the middle of nowhere, it's not profitable to farm.

But a lot of these are dry areas, and so they get taken over by shrubs, and then they become fire hazards. And so the idea comes along. It's like, okay, we can't do traditional livestock rearing here anymore because it's not profitable, but there's no particular reason why we can't have wild game here doing the same thing and creating ecotourism!

Thank you so much for this interview.

Awesome interview that covers an enormous amount of ground. Well done!

Amazing stuff!