The Weekly Anthropocene Interviews: Dr. Angus Hervey, Political Economist at Future Crunch

The world is doing a lot better than you think

Dr. Angus Hervey is the co-founder of Future Crunch, which reports data-driven good news on human progress from around the world. He was previously the founding community manager at Random Hacks of Kindness, and holds a PhD in International Political Economy from the London School of Economics.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Mr. Hervey’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

I'm really excited to talk with you. I actually started my newsletter before I'd even heard of Future Crunch, but once I saw Future Crunch, I'm like, wow, this is someone who's doing a more professional, more developed version of what I'm trying to do. To share with people all the stories that get underreported or decontextualized of all the stuff going right in the world, the amazing wins happening all over the place. To fight against despair with writing.

Thank you very much. I really appreciate the kind words. And also, you know, I wouldn't put your newsletter down at all. I think it's fantastic. I really enjoy it. I think you're doing a fantastic job with it. And I hope that it's going well. I hope you're getting some traction with it.

Yes, I've got like 2,700 and change subscribers on Substack, but that's up from just 300 in January. So that's growing. Going pretty reasonably. I had like only a couple hundred for years and years because [The Weekly Anthropocene] was just my own personal newsletter. It wasn't even really accessible online. I would just collect people's email addresses who I met in real life. But now on Substack there's a bunch of recommendation features and stuff and I've got some network effects.

That's really exciting.

Yeah! So whenever you're ready, I have some questions prepared and some stuff I would like to discuss with you.

Before we jump in, I just wanted to find out a little bit more about you and your background. So you're an environmental journalist. What have you sort of, what have the last few years looked like for you?

Well, I was homeschooled, and then I kind of got into the college track a bit early. So I graduated with my bachelor's degree when I was 18 from the University of Southern Maine. And then I went straight from that to working in Madagascar for a few months. I just republished my blog posts about that on this newsletter.

I’ve kept The Weekly Anthropocene up nearly every week since 2017, which seems like a lot. It's given me, I think, a really decent sense of what's going on in the world, and that's helped me in other aspects of my life.

So then from like 2021 through June 2022, I completed an intensive one-year master's program in GIS, Geographic Information Systems. I found that GIS mapping was a really useful tool to complement work on environmental issues. I currently work as sort of a GIS consultant for a couple different entities, doing maps and data visualizations and story maps and stuff like that of cool stuff that people are doing. And in as much of my spare time as possible, I write this newsletter.

How is that working for you?

Basically, I try to write about really cool, interesting stuff happening in the world. And doing this for the past couple years, it has made me realize that most climate activists, even many professionals involved in climate, have no idea how fast things have changed. Like the Inflation Reduction Act, and more investment in renewables than in fossil fuels this year, and stuff like that. There’s so much good news that people just don't get. People think we're still in 2010 and building coal plants constantly and solar and wind are still sideshows. And that's just not the case at all.

I feel like there's sort of a thread in climate discourse that's very doomist, and I'm trying to counter that and show people that the world's worth fighting for. There's good stuff happening and this is not the “darkest timeline” or any of that stuff that goes by on social media. So I’m trying to show that kind of rational optimism and.…wow, you, you're really interviewing me! In a really good way. Um, thank you. Very effective turning the tables there.

That’s the problem when you have two journalists speaking to each other! I've got a last question for you and then I promise you we can switch the tables. I'm just very curious. There's not many of us out there reporting good news, so it's always really good to find someone. It's like they've almost stumbled into the path of this rare but very compelling idea. It's sort of so compelling that you have to do something about it. And everyone operationalizes it in different ways.

Two people doing this work who I really admire are Steven Pinker and Hannah Ritchie. Steven Pinker wrote a book.

I love it. Enlightenment Now.

And Dr. Ritchie got into it through her research work. Check out her excellent Substack at Sustainability by numbers and her superb recent TED talk. She's now written a book, which is coming out early next year, which I think, which is basically everything that you do personified. It's this link between human development and conservation and environment. It's going to be really good.

I emailed Dr. Ritchie for an interview, but she wasn't available. She sent a very lovely email back saying, I'm so sorry, I'm not available. But yeah, she's amazing.

I would encourage you to keep on trying. She would be a really great interview to do. And yeah, everyone stumbles into it in different ways but once the idea takes hold it doesn't let you go. And there's this weird, very small but slowly growing kind of tribe, I suppose of people around the world who do this work, and we’ve all stumbled into it in different ways, so it's really lovely to meet and talk to somebody else who joins this small but weird little tribe.

Yeah, you kind of can't believe this is a small but real little tribe, because what we're saying is, maybe the world isn't totally awful. Like, it seems like it should be like a default point of view. But that was one of my questions for you.

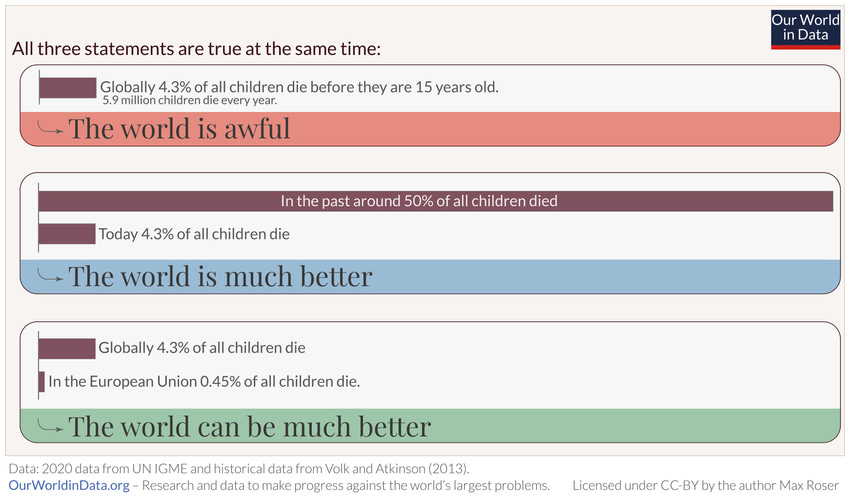

Why do you think, maybe it's human psychology, maybe it's current sort of internet algorithm incentives, maybe it's all of those, but why is there such a negativity bias? Why is everything “if it bleeds, it leads?” Why is the headline always like the “worst thing that happened in the world that day” and not like “125,000 more people rose out of extreme poverty?”

There are three answers to that question, or there are three different versions of that question. One of those answers is rooted in evolutionary biology and two of those answers are rooted in media and the evolution of media in the past two decades. So the answer to evolutionary biology is one that's pretty well known.

You know, human beings have a negativity bias, we tend to pay attention to things that are dangerous and scary. Things that are dangerous and scary tend to be remembered for longer. We retain that information for longer, it takes up an outsized proportion of our attention in our brains. And there's a very good reason for that, which is that we are all descended from a very long line of scaredy cats. The people who didn't pay attention to bad news and who didn't prioritize bad news over good news, fewer of them passed on their genes. By far, the majority of us who are alive today are alive because our ancestors were the ones who preferred bad news to good news. For most of human history, that turned out to be a really great adaptive evolutionary trait because it allowed you to pass on your genes.

But now, by and large, not for everybody, but four-fifths of the world now live in a world where death is not around the corner every day, where many diseases are far less prevalent than they used to be, where the chances of dying by not paying attention to the weather are a lot less. [Yes, this is the case even with climate change: weather-related disasters have increased over the past 50 years, and property damage has increased, but deaths from weather-related disasters have decreased due to better early-warning systems and other factors].

Human biology doesn’t change in a single generation, or even many generations. We’ve got evolutionary hangovers. Which is not to say that we can't overcome those evolutionary hangovers, but it means that if you are trying to promote a message of progress and good news, you are pushing a rock up a hill. The amount of evidence and the amount of messaging that you have to get through is orders of magnitude higher than the amount of messaging and evidence you have to get through if you're trying to promote a message of doom and disaster and destruction.

“If you are trying to promote a message of progress and good news, you are pushing a rock up a hill. The amount of evidence and the amount of messaging that you have to get through is orders of magnitude higher than the amount of messaging and evidence you have to get through if you're trying to promote a message of doom and disaster and destruction.”

-Angus Hervey

So that's the first reason: we have these kind of evolutionary biases that leave us ill-equipped to deal with the world as it currently is.

The second reason is that in the past 20 or 30 years, global media and the practice of media and news organizations has changed. And the reason that they've changed is that there are a number of reasons that they've changed, but essentially what's happened is that their audience has fragmented, the business model of journalism has changed, and it's essentially changed from a business model of advertising to a business model of attention. The attention economy has required media organisations to change the tenor and the tone of their messaging. And a big study came out last year that analysed, I think it analysed headlines from something like tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of headlines from something like 350 or 400 news organizations across the United States. And it analyzed those headlines over 20 years.

And what it found was that there had been a significant decline in the sentiment that was expressed in newspaper headlines. It wasn't people's impressions, this was actually evidence-based. Newspaper headlines have become significantly more scary. They've become more filled with stories of doom. The newspaper headlines tended to be more sensationalist, more shocking and more scary than they were 20 years ago. So this has kind of compounded the negativity bias. And of course, this creates a horrible feedback loop.

If you think the world is a terrible place, or if you tend to pay more attention to bad news than good news, then the news organizations are putting out more messages of bad news that makes you feel more negative about the world. Then because of confirmation bias, you go out looking for more news that confirms your preexisting notion. And of course, there's more of it out there. And so the whole cycle kind of starts again. More people are clicking on those headlines. The news organizations are saying, great, these headlines are working. We're getting more attention for them. And so there's this horrible feedback loop.

If you go to the front page of any of the top news sites in the world, four out of five of those stories on average will be bad news stories. And the remaining 20% of stories are often things about celebrities or sport. People who have been blessed with great bone structure and good hair, or people that have been blessed with genes that can make them run fast or jump very high.

So that's essentially what our news organizations are doing. And what that means is that humanity's sense-making organs are just atrophied. They've gone horribly awry. We have a kind of collective disability to make sense of the world.

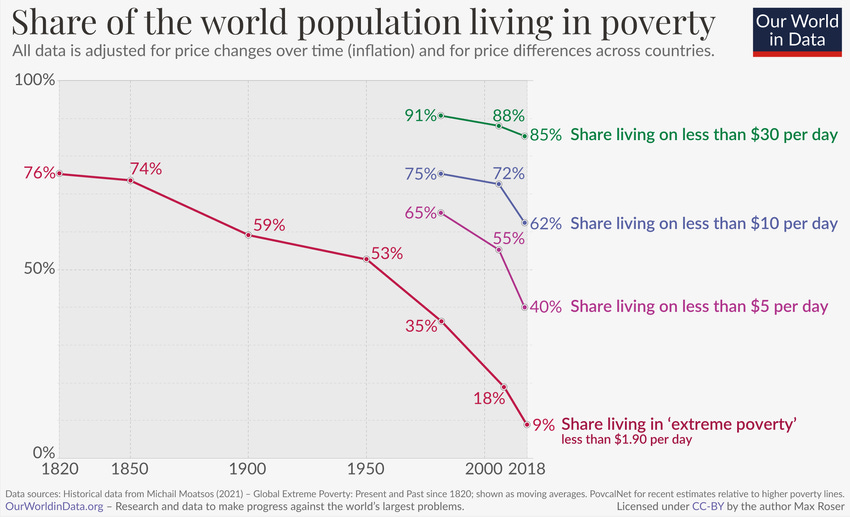

I’ll give you a recent example. UNICEF has just published a study. It’s their first ever big measure of child poverty, extreme child poverty in the world. And what this study showed is, it found that the number of children who are living in extreme poverty has fallen by 49.2 million between 2013 and 2022. There are nearly 50 million fewer children living in extreme poverty compared to ten years ago!

But the headline of every single one of the stories about the report was not “50 million children have been lifted out of extreme poverty.” The headline of every single story was “333 million children still live in extreme poverty and the pandemic set back efforts on poverty eradication by three years.” So if you just read the headline of this UNICEF study, it looks like a bad news story. But then when you go into the actual statistics, the statistics say nearly 50 million children got lifted out of poverty in the last ten years. If COVID-19 hadn't happened, it would have been nearly 80 million. but unfortunately, we got set back by a pandemic. But it's still incredible progress!

I've often found many news stories are factually accurate, they actually have that information buried in a paragraph somewhere. But they’re just constructed in a way to give off sort of a negative affect, they sort of emphasize the negative and sort of de-emphasize the positive.

And there's a reason for that, because you are more likely to click on that headline if it's a negative headline. So, this kind of brings me to the third reason why bad news is such a problem, which is that essentially what's happened is we poured fuel onto the fire in the form of social media. It's important to remember that social media is only about 6,000 days old. We only invented it about 6,000 days ago. And what social media does is, when there’s a bad news story that is written or reported on by a news organization, that story spreads like wildfire throughout the global network.

And what that means is that you are now getting bad news stories, both in your social media feeds and on the pages of newspapers, from everywhere in the world all at once.

So it means you're now reading about war in Azerbaijan, flood damage in Madagascar, someone being murdered in their home in the UK, children being burnt in an accident in Chicago, and someone in Greece being robbed of their jewels while they're on holiday. It means that you're getting this torrent of bad news everywhere all the time. What that does is, it just warps your view of the world.

If the majority of those stories tend to be bad news stories, which is what social media rewards and what news organizations are desperate to create because it gets them more attention and more clicks, then what happens is it just gives you, subconsciously, this terrible impression of what's actually happening in the world. The world feels like an awful, awful place.

I absolutely agree, that media dynamic is really troublesome. Let's move to the specifics. One big thing that I really try to push back on in my writing is people's perception of developing countries, which often seems to be stuck in about 1965. People are still stuck in this sort of Paul Ehrlich-like idea that all of South Asia and Africa and Latin America all have super high TFRs and are all still deep in extreme poverty. People are still mentally stuck in the idea of the West and the Rest.

Can we talk about, can you summarize for someone who maybe only reads bad news stories—this is a huge, huge ask, of course—but the real economic state of the world? Like the fact that, you know, most people aren't living in desperately poor countries right now. Like, let's start with India, let's start with the amazing stuff happening in India that people don't know about.

There's a couple of ways of tackling that question. Maybe one way is to talk about the people who are living at the bottom of that pile; there's just far fewer of them today than there used to be. And I'll start with the three most populous countries in the world, not including the United States.

So the three most populous countries in the world, not including the United States, which is third, are China, India, and Indonesia. Those countries have a combined population of over 3 billion, so you're looking at three-eighths of the world's population. It's not quite half, but it's getting close to it. India and China are two of the three most important countries in the world, and Indonesia is pretty close.

India has pulled off one of the greatest poverty eradication efforts of all time. It's kind of followed closely on the heels of China. China's poverty eradication efforts are fairly well known, China's lifted more than 500 million people out of poverty in a single generation, which is arguably the greatest economic story of all time. But India has followed pretty closely behind. India's just released, I think you must have seen it, the 2018 multi-dimensional poverty index in India, which found that over 270 million people in India have been lifted out of poverty between the 2005-2006 period and the 2015-2016 period.

India has pulled off one of the greatest poverty eradication efforts of all time….270 million people in India have been lifted out of poverty between the 2005-2006 period and the 2015-2016 period.

But the one that I think actually gets the least amount of attention, which is arguably the most incredible, is Indonesia, which is the largest Muslim country in the world. It has a population of over 250 million people. And it's very tricky because it's basically a country that's just strung out over hundreds of islands, it's kind of very fragmented. So it has a lot against it, you know. It's not able to have rail routes and roads and big infrastructure in the way that we kind of assume development requires. And yet Indonesia has managed to reduce extreme poverty [living on less than $2.10 per day] to less than 2% in the last few years! In Indonesia, extreme poverty has essentially been eliminated, and just 16% of the population are poor [living on less than $3.65 per day] - down from over 50% two decades ago. Childhood stunting, which is a major problem and a huge indicator of poverty, childhood stunting has dropped precipitously. I'll just quickly get the statistics on that. Give me one second.

I'll be going back and adding links to this, the sources of the statistics.

I'll just tell you very quickly on stunting. I'll roll the data.

So India, 16 million fewer children in India stunted today than there were in 2012. Prevalence of stunting has fallen from 42% to 32% during the last decade. So that's India.

Incredible.

The stunting in Nepal has more than halved in the past 26 years. In Ghana, the proportion of children under five suffering from stunting has fallen from 35% in 2003 to 17% in 2022, so that's halving of stunting again in Ghana. In Cambodia, childhood stunting has fallen from 34% to 22% in the last eight years. And then Indonesia is my favorite. In Indonesia, between 2018 and 2022, the national stunting rate fell from 30.8% to 21.6%. In Indonesia today, over 10.6 million more children than four years ago are benefiting from anti-stunting interventions.

So look, I mean, nothing I'm saying here will be news to you, but you can take any one of these indicators, extreme poverty, maternal health, childhood deaths, stunting. Malnutrition has had setbacks in the last two or three years, largely because of the pandemic and sort of global economic disruption. But it looks like nutrition is kind of back on track.

Access to electricity, I just wrote about that in the most recent newsletter, it's back on track this year. So this year, the number of people without access to electricity will fall by about 15 million.

Education has also seen huge setbacks in the last two or three years, but it looks like that's back on track. Poverty eradication efforts generally.

Everywhere you look on any of these indicators on rising living standards and human well-being, those indicators are moving in the right direction. And yet that story is just almost nowhere.

People don't get that. People think that the world's stagnating or something, or that we have internet maybe, but poverty is still entrenched. But in all these countries around the world, from Ghana to Kenya to Morocco to India to Cambodia to Indonesia, life is getting so much better so fast. And that is just amazing.

Moving on, and I'm just sort of scanning across a lot of things, global poverty reduction is huge but the other thing most people really don't know is: there's a lot more good news for wildlife than people think. I don't know if you saw Our World in Data’s chart on wildlife making a comeback in Europe, but beaver numbers in Europe have grown by like 16,000% since 1960.

There are similar stories in many other parts of the world. There's humpback whales in New York Harbor, there's caracals in Cape Town, there's leopards in Mumbai. I try to write about this as much as possible. There's otters and a Malayan tapir just swam over to a park in Singapore. That's like a wild bison coming to Manhattan Island!

My favorite story is that in Southern Africa, elephant populations are up by five percent.

Yes, I just wrote that in my newsletter!

Yeah! They're still being poached and attacked, but we are pushing back on that. Conservation efforts are working, anti-poaching efforts are working. Giraffe populations in Africa are on the rise again after dipping for quite a while. The story of tiger conservation is one of the great conservation success stories of the last 20 years, as is humpback whales. Sea turtles look like they're starting to recover now as well in multiple populations around the world. And yet people who are on the front lines fighting for these things don't understand these stories.

Sometimes people on the frontlines of turtle conservation say, they’re doing this because populations of green sea turtles are declining worldwide. And that’s just not true. Green sea turtle populations are increasing worldwide. And the reason that sea turtle populations are recovering is because of people like them!

Imagine a group of people who tried to improve life, and as they started doing it, no one who was working on trying to make things better was allowed to hear any stories about the fact that their work was actually succeeding. What would happen is that after a year or two or a few years of doing that work, they would just stop doing it because if you couldn't see the fruits of your labour or you didn't hear the story about how what you were doing was actually starting to make a difference, then you would lose hope and stop doing it.

Or what would happen is only one or two people would still be doing the work because it was such thankless, difficult work that only people who are true saints would actually be able to keep on going.

The thing about hope is that hope is not faith. It's not faith that things are going to turn out better. Hope is much more robust. It's based on evidence. It's rooted in understanding that things can change and that they are changing. And yet at the same time, hope has that kind of element of inspiration. You don't understand the story unless you actually seek out these stories of progress. They're not going to come to you. So you have to make an active decision to be optimistic.

And in that sense, optimism isn't a reaction to the world around you.

It's a choice by which you navigate the world around you.

And in making that choice, the world suddenly starts looking very different.

So on those two fronts, on the human rights and material well-being and certainly on public health and disease where the progress has just been extraordinary, I think things are getting better. But at the same time we're kind of also entering this kind of narrow funnel where that seems to have come at the expense of the environment, or certainly has for the last hundred years.

Now, on climate change, things seem to be turning around quite rapidly. I've said this in the most recent newsletter, the most important climate story in the world right now is what's happening with solar in China, and yet it's barely being reported by any mainstream news organization. A new report from Rystad now estimates that China's installed solar capacity will cross the 500 GW mark by the end of the year and will then double again to 1 terawatt by the end of 2026. And over at Bloomberg, they're now saying that global solar installations will rise by 56% in 2023. Those kinds of figures blow every previous prediction out of the water.

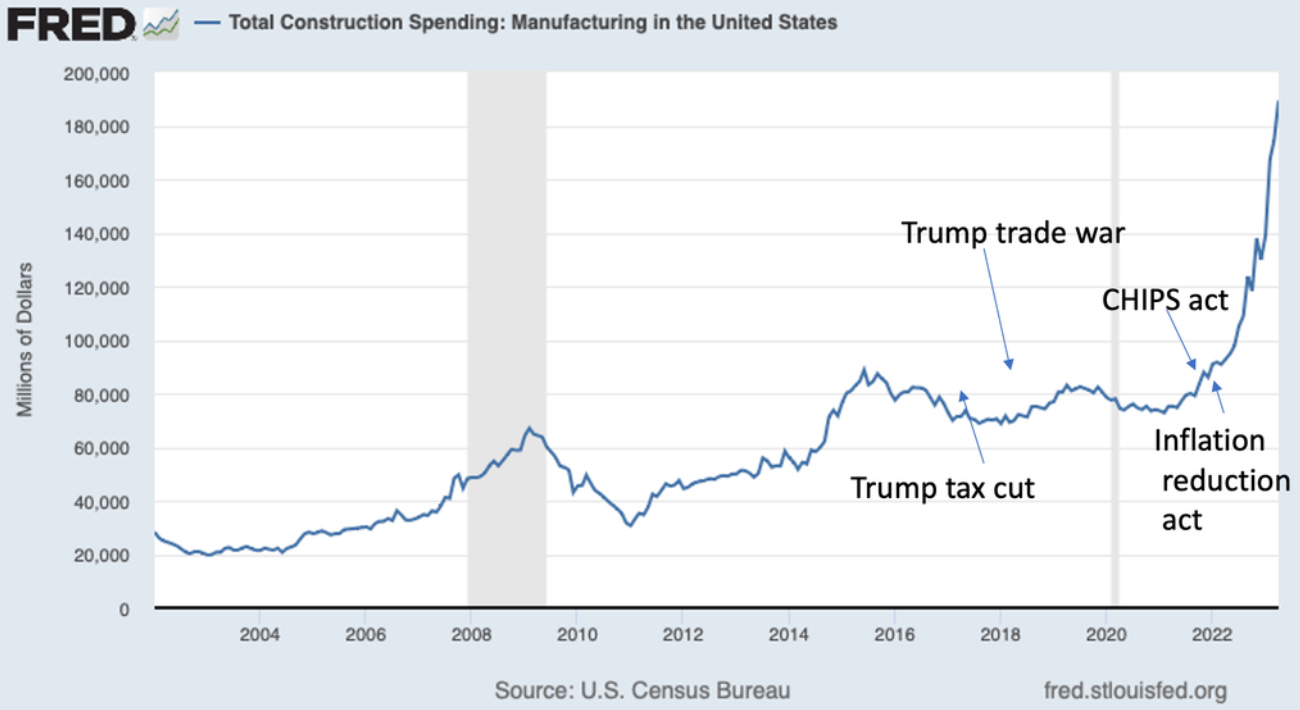

Yes, absolutely! And, in the non-China part of the world, the Inflation Reduction Act! I constantly talk about the Inflation Reduction Act, just because I have a little more perspective on American issues than Chinese issues. You're familiar with the Inflation Reduction Act, right?

Very, yeah, I've written a lot about it, I understand it very well.

I thought so, yeah, because no one else is! Like, I talked to someone recently, a PhD who was actually studying protein folding, a really really smart person, and she's like, what is the Inflation Reduction Act? And I'm like, it's the biggest freaking investment in America since the New Deal.

It is this unbelievable titanic investment. The graph of U.S. manufacturing investment under Biden looks like a hockey stick, exponential growth. The investment in American, solar, battery, electric vehicle manufacturing is incredible. And the projections! The EPA is saying it [the Inflation Reduction Act] might reduce like electric sector emissions by up to 83 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. It is actually appropriate to the scale of the problem of climate change. It's a freaking miracle! And yet the average climate activist still just sees social media memes about like, Biden approving one oil project in Alaska, which I don't agree with, but it's was done to like appease Lisa Murkowski and swing senators and he probably didn't have legal authority to stop it anyway. And it might end up not producing oil at all: see my full article. I would love to tell other climate activists: be able to accept wins and celebrate wins! Because otherwise, you just drive people to despair. And people are being driven to despair.

So, what are your thoughts on that? What is your perspective on how people have missed the insane shift towards renewables in the last three years and the likely future of exponential growth in clean energy?

The Inflation Reduction Act, as good as the news is on the Inflation Reduction Act, what most people I think don't understand is that it's just so much bigger than the headline figures. Because the headline figures in the Inflation Reduction Act, which was like $372 billion or something like that [of federal investment] that's just a fraction. It mobilizes trillions of dollars of private investment! Because what it does is it essentially says the government is saying, look, we are guaranteeing that we're going to do this come hell or high water for the next 10 or 15 years. And so the actual investments that are happening as a result of the Inflation Reduction Act are orders of magnitude higher than that figure.

The other thing that I think is really interesting with the Inflation Reduction Act is that although mainstream news organizations have not been doing great reporting on it, I think what makes it so powerful is that the on the ground effects can really be felt. And they are being felt by the people that need to feel it, which is people that live in red states. Most of the investments that have happened as a result of the IRA have happened in red states.

And down there when a new factory opens, or when a new solar plant gets inaugurated or when the myriad of the hundreds of other ancillary services spring up in order to support that new battery factory, everything from takeaway shops to rental accommodation to new bars, that is all stuff that gets felt on a daily level by ordinary people that don't necessarily make it into the news. I think what that does is it turns climate change and clean energy from a partisan issue into one that is just an economic issue. And so it means that people aren't opposed to solving climate change, because it means that it gives them a good steady job.

My favorite recent statistic from the IRA was that there's been $242 billion of clean energy investments since the passage of the IRA. But there's also been the creation of over 142,000 jobs now.

I think that that’s right in that people know when they’re working on a battery factory or a solar farm. But I worry that the roots of this stuff, the policy and the reasons why good stuff happens, are just not seen by people.

I think that most Americans are a lot smarter than media organizations give them credit for. And people understand that a new solar panel factory doesn't just drop out of the blue to a part of deep rural Georgia that hasn't had any investment for 25 years. [For example, thanks to Biden’s IRA, the biggest solar panel factory in the Western Hemisphere is expanding in a Trump-voting rural county in Georgia]. It doesn't just happen by magic.

What question have I not asked that I should ask? What do you really want to show people?

The stuff that I'm probably most excited about is disease eradication and public health in terms of what's happening in the world that people don't know about, which again is just astonishing.

I mean, we've got gene therapy eye drops and GLP-1 agonists and like all this amazing new technology coming out.

Well, those things are really exciting, but I actually think the thing that's most exciting is very basic public health.

Vaccinations, preventable diseases, treatment of neglected tropical diseases. Something like, compared to a decade ago, 500 million fewer people are at risk from neglected tropical diseases. And what most people don't understand is that a neglected tropical disease is really fucking horrible. Most of them don't kill you, but they're really agonizing, awful diseases to suffer. You know, elephantiasis, leprosy, trachoma. These diseases are disfiguring, they're painful, and they have a huge effect on individual lives. River blindness, guinea worm, these diseases have affected and afflicted human beings for thousands of years, they have always been with us.

And what's starting to happen now in our generation, is that for the first time ever, the actual end of these diseases is now in sight!

Most people kind of know the story that smallpox was eradicated. It looks like guinea worm is going to be the next disease that gets eradicated before polio, because polio is so difficult to get to the last mile. So guinea worm is probably next up.

But leprosy, leprosy cases have declined by around 20% since 2013. Nigeria has just eliminated neonatal and maternal tetanus in northwestern Nigeria, which is home to 30 million people. Iraq eliminated trachoma, which is the most common infectious cause of blindness in the world. And that became the 50th country to eliminate a neglected tropical disease since 2013, which means that we're halfway towards 100 countries eliminating a neglected tropical disease by 2030. I mean, that's incredible progress in a single generation. Bhutan and Timor-Leste eliminated rubella this year.

For trachoma generally, the number of people at risk globally has fallen from 1.5 billion in 2002 to 115 million today.

Wow, 1.5 billion. That's more than an order of magnitude. That's incredible.

Yeah, 1.5 billion people in 2002 were at risk from trachoma, a disease that literally caused them to be blind. Today, that's 115 million. And of course there's malaria, which is starting to decline. AIDS has seen a precipitous decline.

We’ve got malaria vaccines!

Malaria has probably killed more people than any disease in human history. The fact that we have a vaccine for it now is absolutely incredible.

I think what would be so interesting in media is what would a media look like where the habits of reporters were geared towards being able to tell those kinds of stories?

The fact that Iraq has eliminated trachoma, to me, that feels like a really compelling story. Why was there not a New York Times front page feature on the big personalities involved in that story, you know, a hero's journey where this disease felt impossible to eliminate 20 years ago, it was afflicting all these different people, but a small but bold band of people decided they were going to take on this impossible task and through war and the invasion and everything that was happening around in Iraq. They fought on and persevered and then in 2023 officials from the World Health Organization descended on this country and declared it to be free of trachoma. It’s this amazing Story of Human Triumph in the Face of Incredible Odds! Why do we not know how to tell those stories on newspapers?

It's been great talking with you. I really, really enjoyed this conversation. You know you can sometimes feel like when you keep having to explain to people, no, the world actually isn't terrible, you start thinking, am I the crazy one? But talking with other people really familiar with the data that shows what's getting better, that's a really good feeling. So I appreciate this conversation.

Oh, it's such a pleasure, thanks very much. You know, keep on keeping on! I've been researching and talking about this for years. I think it's really important work. And I'd really just encourage you to just keep on going. The world, we need so many more people to be telling the story. There's so much more room for it. It is not a competitive space because there's just so much space that needs to be filled up. So, you know, please keep on doing what you're doing.

Thank you.

Worth the read, thanks. One point on population and poverty - even though 125,000 more people rose out of extreme poverty each day the total population rose by 190,000. Not sure where the 65,000 end up. Unfortunately I expect there are more people in poverty now than at any time in history, probably more than the entire pre-industrial population, so I am a bit wary of claiming poverty reduction as a great victory for industrialization.

Great interview Sam! You two are very much bird of a feather! In defense of the doom and gloom community--it is our warnings and focus on the negatives that drives the reforms and improvements worldwide that you note! Neither community can exist without the other!