The Weekly Anthropocene Interviews: Noah Smith

An Exclusive The Weekly Anthropocene Interview

Noah Smith is an economist and economics writer formerly associated with Stony Brook University and Bloomberg News; now an independent Substacker at Noahpinion. He’s written extensively on the economics and geopolitics of renewable energy.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Mr. Smith’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

What are your thoughts on the Inflation Reduction Act and its multifarious results? From reducing emissions to unlocking a boom in climate VC to potentially revitalizing a "Battery Belt" in the Midwest to potentially unleashing a trade/subsidy war with the EU and East Asia to boosting America's global R&D and manufacturing role, et cetera.

Well, I think the most important function of the Inflation Reduction Act is green energy investment. I think everyone agrees this wasn’t about inflation. Although there’s a couple Democratic social spending priorities in there, by far the bulk of the spending goes towards subsidies for clean energy technologies. And some subsidies for fossil fuels, which a lot of climate activists are not happy about but which was politically necessary because of the Russian situation where energy prices were spiking. So that may have helped with inflation a little bit. But mostly it’s about clean energy. There are actually three purposes to this massive buildout of clean energy.

The first main purpose, of course, is climate change, which progressives care about and which everyone in the country should care about. It’s pretty clear at this point that no degrowth-style solution is going to happen, nor would it be good if it did happen. The answer to climate change is not to overthrow capitalism or to reduce the rate of growth or shrink rich economies, or any of this crazy stuff that people in the UK like to talk about. Instead, it’s just going to be that we’re going to switch to clean energy, and that’s going to be the solution. And so, that means getting rid of coal, eventually getting rid of gas, getting rid of oil as well. And that’s what the IRA is really about. It provides massive subsidies to replace gas cars with electric cars, and to build out green energy like solar power. And so that’s the first purpose.

The second purpose is to speed the energy transition to make us actually richer. This idea of abundance, that is a thing that people don’t really understand yet. Most people still believe that renewables are more expensive than fossil fuels, and that we’re actually making an economic sacrifice to switch from fossil fuels to renewables. That is increasingly not true. Because renewables have gotten so cheap that now on the margin, and eventually in totality, it is and will be cheaper to switch from fossil fuels to renewables. That actually gives us cheaper electricity, and with that cheaper electricity we can do all sorts of cool things. We can drive our cars without ever filling up a tank. That’s gonna be fun! We can desalinate water, produce tons of aluminum, supercharge advanced manufacturing. All sorts of things we can do with cheap electricity, because renewables are simply cheaper than fossil fuels now.

The third purpose, as you said, is geopolitical. I would say it’s less in terms of staying competitive in the battery industry versus China-although we will do that-it’s mostly about getting the world off of oil in terms of transportation. So, converting a lot of the world’s transportation to battery electric vehicles will massively reduce the profit and therefore the power of Russia and Iran, two of our major geopolitical rivals now. The third being China. Russia and Iran are petrostates, and certainly switching to EVs will reduce the power of those petrostates quite a lot.

This neatly segues into the next question, which is: a lot of the key minerals for the renewables transition are currently from China. How do we avoid China becoming an “electrostate,” gaining geopolitical clout based on their exportation of rare earth elements? How do we handle the renewables transition and geopolitical conflict with China at the same time?

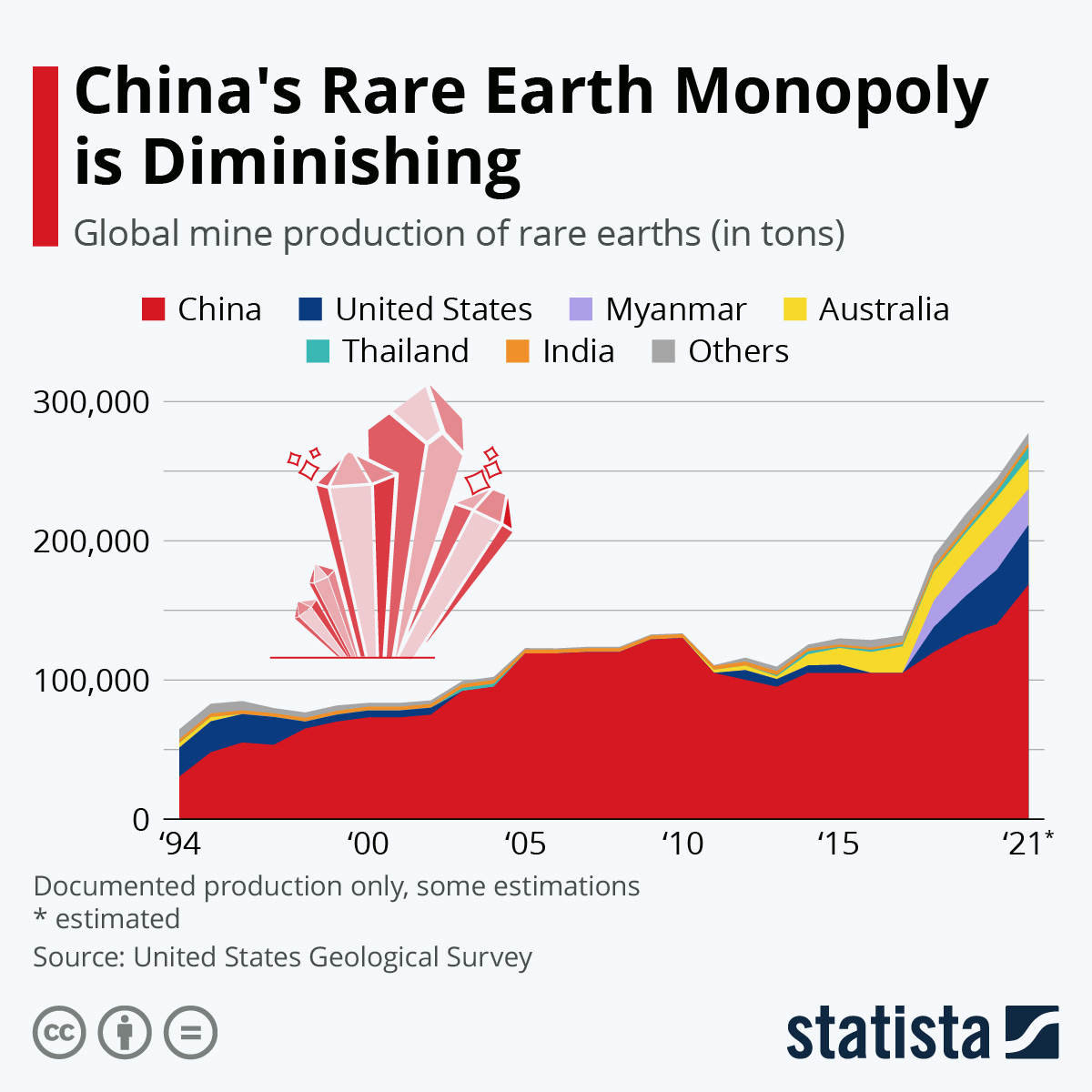

It really depends on the mineral. Copper, for example, you’re not talking about China, you’re talking about Chile. Cobalt is increasingly not used in batteries. Cobalt, that’s a non-story, because we’re switching to lithium-iron-phosphate chemistries that do not use cobalt. Nickel is still somewhat important, but lithium and copper are the main metals here. And the problem is not that China mines these things. People talk about China having a chokehold on mining, but China attempted to weaponize the rare earth weapon against Japan several years ago [this happened in 2010], and Japan simply very very quickly found a way to extract rare earths fairly cheaply from the seabed, and now is independent in rare earths. It’s fairly easy to mine our own rare earths. [To clarify: rare earths are a set of 17 different elements with similar properties, and do NOT include copper, lithium, or cobalt. However, they are are also extremely useful in batteries and other high-end technologies].

What we’re really talking about in respect to these clean energy transition minerals is mineral processing, not mineral mining. [This is accurate: China has only 7.9% of the world’s lithium reserves, but 60% of its lithium processing and refining capacity. Similarly, China mines just 8.5% of the world’s copper (Chile mines 28.5%) but produced about 42% of the world’s refined copper as of 2020]. Mineral processing is essentially a large volume, capital intensive, low margin, low tech business. You take some ore, you crush it, you pour some chemicals on it, you heat it up maybe, et cetera. It’s not very hard, you just have to build these very large plants. When you hear the words industrial machinery, you probably think of a mineral refining plant. We let China do that for one very specific reason, which is that it’s low margin. You don’t get a big return on equity, it’s capital intensive and low margin. In other words, for an American company to do that mineral processing would require it to go out and borrow tens of billions of dollars and get just a little bit more than that back. That’s not the kind of financial return American companies are used to. Technologically, there’s nothing that we really can’t do there, and China doesn’t have the actual mining of the ore for these minerals. If we want to, we can easily set up some copper refining and lithium refining operations here in the United States or in any cheaper allied country that wants to get some of this economic activity. We can do it in India, all kind of places. We can do this refining anywhere we want, it’s not really much of a strategic vulnerability at all. The only issue would be if we don’t build any of those facilities, and then a war breaks out and China abruptly cuts us off. It would take time to build those processing facilities, and we’d have to rely on stored-up stocks. it would cause a crunch, similar to what happened at the beginning of COVID when we got cut off from our supply of masks and ventilators from China.

[And remember, all this mining for renewables still adds up to orders of magnitude less mining than the fossil fuel economy, because coal, oil, and natural gas are constantly consumed but the same small amount of lithium stays in a battery for years. As Dr. Hannah Ritchie writes in her excellent article: we currently mine 7 million tonnes of minerals for clean technologies every year (which could rise to 28 million tonnes by 2040 with rapid renewables deployment), compared 15 billion (15,000 million) tonnes of fossil fuels per year!]

You’ve written a lot about NEPA [a core US permitting and environmental protection law that mandates that any project receiving federal funds or permits write an in-depth report of the likely environmental impact], and that’s relevant to a lot of American critical mineral sourcing [and renewables buildout]. Basically, NEPA used to be environmentalism’s best friend for a long time when we focused on stopping a lot of bad stuff from happening, and now that we need to make a lot of good stuff happen [renewables, critical minerals mining], it’s starting to become arguably an impediment to the renewables transition. And my personal background, one of my academic mentors was an expert on NEPA and taught courses on NEPA, and it’s saved a lot of special places from fossil fuel mining and stuff. For the environmental audience, it’s a difficult mental switch to realize, this thing that we have really strong positive associations with might be causing some harm now. Could you unpack that?

The thing about NEPA is that it’s a procedural requirement rather than a substantive requirement. What that means is it’s more about how we enforce environmental laws and it’s not at all about what the environmental laws actually protect. It’s about the method of enforcement. It’s more like policing than courtroom law. That’s what NEPA is, and the problem with NEPA is that it is what some scholars call a low-end strategy of state policy. High-end strategies are when the state does it itself, the government creates an army of bureaucrats to enforce environmental law. This is how Japan does it. The alternative is to essentially farm it out to local interests, and say instead of having a large government bureaucracy to do this, we’re gonna let local people simply sue in court to stop projects by demanding these environmental reviews. So they’ve farmed out environment enforcement to local people. This was very attractive to people who, for example, didn’t want a big highway destroying their community because some distant planner in a state capital decided there should be a highway there to create jobs, right? Or if there’s some chemical factory that’ll poison your kids, you could wait twenty years and file a class action lawsuit, or you could just stop it with NEPA. So there were lots of cases where people preferred the local interest approach because there really is a lot of local stuff where communities have concerns about projects. And the problem with this is that when the central government finally wants to do something important, local interests can block it. And the local interests often do not have interests that are aligned with the federal government. For example, if you really love the view of the mesa outside your house, and you simply think it’s aesthetically displeasing to have it covered in solar panels. And the central government says, no, we have to build solar panels to fight climate change. And you say, no, I like the view of my mesa, build them somewhere else. Then you can use NEPA to hold up that project for months or even years by demanding environmental impact statements, the longest, lengthiest, most cumbersome form of NEPA reviews, that take years to do, and you can gum up the process. (Here’s the Noah Smith article on the real-world solar mesa case). Even the threat of being able to gum up the process like that often is a credible threat, that makes developers not even propose a project in the first place because it’ll be delayed to the point of unprofitability.

NEPA was always a risky strategy because low-end strategies of state formation are always vulnerable to the idea that parochial interests don’t have interests aligned with the government that’s farming the work out to them. People who defend NEPA often say, well, if you want an alternative to NEPA, you could actually staff the federal bureaucracy more effectively, hire more people. That’s actually true, but I’d say that’s more an an alternative approach to NEPA than a complement to NEPA. That’s not a way to make NEPA better, that’s something better than NEPA. I would say that ideally, we should put a lot more environmental enforcement under the control of the federal bureaucracy, which has to be well funded and well staffed, than farming it out to any NIMBY who likes the view of their mesa and so refuses a solar plant.

“Ideally, we should put a lot more environmental enforcement under the control of the federal bureaucracy, which has to be well funded and well staffed, than farming it out to any NIMBY who likes the view of their mesa and so refuses a solar plant.”

-Noah Smith

What do you think of the long-running controversy over tariffs and import bans on Chinese (or suspected Chinese) solar panels, particularly its recent manifestation with the Auxin Solar Commerce Dept. complaint in early 2022 over Southeast Asian solar panels from places like Cambodia and Malaysia [and Thailand and Vietnam] that were merely linked to Chinese companies? Obviously we don't want to fund slave labor in Xinjiang, but we also don't want to overshoot and slow down US solar buildout. And obviously we want to build out the US solar supply chain too, but that takes time.

I think the more effective way to accomplish those goals is subsidies rather than tariffs. Subsidizing US-made solar panels will decrease the price and increase the amount of solar that is ultimately deployed. And it will preserve some domestic capacity, and it will reduce the world’s reliance on slave labor from Xinjiang. Subsidies are really the answer here rather than tariffs. Tariffs drive up prices and reduce the amount that we install. But subsidies are great, because we can’t put a tariff on French imports of Chinese solar panels. We can’t. We can’t put a tariff on African imports of Chinese panels, or Japanese imports of Chinese solar panels, et cetera, but we can subsidize our own. And if we subsidize our solar panels so that our solar panels are competitively cheap, our solar panels can displace Chinese solar panels not just in the domestic market but in world markets as well where we have no form of tariff control.

“If we subsidize our solar panels so that our solar panels are competitively cheap, our solar panels can displace Chinese solar panels not just in the domestic market but in world markets as well where we have no form of tariff control.”

-Noah Smith

So that Japanese and French and African solar panel installers will install American solar panels just because they’re cheaper, because they’re subsidized. So a subsidy war where we try to make our solar panels as cheap as possible through subsidies is the answer.

What are your thoughts on the transition to EVs and its geopolitical implications? China’s building a lot of EVs, we’re also subsidizing them with the Inflation Reduction Act, there’s a need to move to EVs rapidly to reduce reliance on petrostates…

Everything’s looking very, very good. China is building a ton of EVs and that’s great, we really really need that. China’s building some of these for exports, although car exports will never be that big of a deal for one simple reason, which is that a car is a very heavy thing. The weight per dollar of value per cars makes it very, very unattractive to ship cars across the world. That’s why you see most places have a car industry, because most places make cars locally. Even, for example, Hyundai and Volkswagen and Toyota are making cars for the American market in America. The company that owns them is elsewhere, but the factories are here in America. Toyota’s cars are more American-made than GM’s cars or Ford’s. Cars are typically made locally, so China making electric cars is great. It’s not enough, because China needs to switch their grid away from coal; China is now by far the biggest coal offender in the world. That’s where most of the coal in the world gets burned, it’s China. When China is making EVs, and they’re driving around EVs, those EVs are powered by coal more likely, whereas American EVs will now be [more likely to be} powered by natural gas, and in the future by solar and wind. China needs to kill the coal industry and leave that coal in the ground, and that’s a very, very thorny problem for climate change. But, it’s not something we have direct control over.

China switching to EVs and America switching to EVs are great from a geopolitical standpoint as well as an environment standpoint, because they weaken the power of the petrostates, Iran and Russia. They’re going to lower demand. So the thing about oil is that short-term supply of oil is pretty inelastic. It takes a very long time to find and drill for more oil. There used to be this thing called spare capacity, where essentially Saudi Arabia had some unused oil fields and whenever the oil price went up Saudi Arabia would just tap those fields a bit and the price would go back down. We’ve mostly run out of spare capacity now, and so now, we’ve got big swings in oil prices. You’ll notice when Russia invaded Ukraine, we put sanctions on them, immediately the oil price surged to incredible heights. And then it crashed again. Because Russia started selling their oil at a steep discount to India and China and that basically restored global supply. America fracked a bit more, everywhere else drilled a bit more. And so global supply got restored, price just crashed. It’s now back to down around $70 [per barrel], that’s pretty average, historically. Oil’s very sensitive to these movements. So switching the global passenger car fleet to 50% EVs over several years, that will be a heavy blow to Russia and Iran. And you remember if you’ve read Yegor Gaidar’s Collapse of an Empire, which is about collapse of the Soviet economy in the late 1980s, he says-and he was working for them at that time, he was a major official-he says the big thing was just the oil price collapse. At that time, the reason for that was the breaking of the OPEC cartel. So when the OPEC cartel got broken and couldn’t fix prices anymore, oil prices collapsed in the mid-80s. That price collapse completely annihilated the Soviet economic model. Similarly, if oil price collapses, if we can use demand reductions to get oil down to $30 a barrel because nobody wants it, Russia and Iran are in a tight spot. They’ll have to figure out something else to do economically. That’ll make sanctions bite more than they do, and make them a little less adventurous geopolitically in terms of invading countries and supporting invasions of countries.

What are your thoughts on modern rapidly-improving battery technology in general? You’ve written about its potential to be a smartphone-level source of change, transforming everything from war to home appliances to grid-scale energy storage. Most people know about batteries for EVs and grid-scale energy storage, what’s the next wave of battery transformation?

There’s a number of things that batteries enable. Batteries, of course, enable EVs, everyone knows about that. I think e-bikes and e-scooters will be more important than people realize. We haven’t even started doing electric ships, although that’s harder. But more importantly, everybody thinks about batteries for storage of electricity. You don’t have sun during the night, so you charge your battery during the day and use it to run your house at night. Everyone thinks about that as well. And those are extremely important, huge applications, but there are a lot of other things batteries enable as well.

One thing batteries enable is better appliances. You can have little electric leaf blowers that are much easier to carry around than gas appliances. Because the battery lacks the giant cumbersome energy extraction machinery that you need to burn gasoline. And it also lacks the fumes, so that’s nice. The company I invested in, Impulse, is making extremely powerful battery-powered appliances for the home, where you can basically cook your food really fast on high heat, or dry your clothes real fast, or cool your house down, et cetera, et cetera. (Here’s the Noahpinion article on Impulse and battery-powered appliances). You can do that stuff with a rapid discharge battery without rewiring your whole house to have higher-powered wires in the walls. Right now we can’t do any of that stuff just with the wires in the walls, because they burn out the walls. But if you can charge a battery and then discharge it rapidly, you can do this.

But I think the biggest application of all is going to be robots. Robots that are plugged in, they have them in some factories, but they’re inherently limited. Robots need to move around. You need little robots to crawl over solar panels and wash them, construction robots to build buildings from the ground up. They need to be portable. We need energy portability, and batteries are going to be the way that we get that. We’re going to have the world come alive, in a way, because of batteries, there’s going to be robots everywhere because now we can finally allow them to carry energy around in a safe, dense, portable way.

That’s a really cool perspective. I think a lot of people think of “robots and AI” and “renewable energy” and sort of separate tracks, but they really are fundamentally interconnected.

Oh yeah, they go together like peanut butter and jelly.

What are your thoughts on hydrogen? I’ve seen some strong arguments for hydrogen, and I’ve also seen arguments that it’s a really huge waste of time and resources, that batteries are so good they’ll do everything hydrogen can and do it better. There’s some stuff hydrogen just doesn’t work for, like cars. But in your analysis, you found that there is some stuff hydrogen does work for, and that electrolysis is a valuable technology for the renewables revolution. [Check out the Noahpinion review of hydrogen’s pitfalls and potential]. Could you outline the case for hydrogen?

The thing about hydrogen is that hydrogen’s main limitation is that it is expensive to convert water to hydrogen. You have to spend a lot of power for electrolysis, cracking water into hydrogen and oxygen. That involves some efficiency losses of energy. And it’s also difficult to store hydrogen, because hydrogen is a very small molecule. Unless you put it in a very, very solid, sealed, extremely airtight container, it will leak. And any container will leak a little bit. Hydrogen just leaks much more easily than anything else. And so it’s difficult to transport it because of the leakage. It’ll leak right out of a pipeline. So that’s the limitation of hydrogen.

The advantage of hydrogen is that it’s a chemically stable thing, and the feed stock is just seawater. You can crack any water into hydrogen and oxygen, it’s very easy to get that feedstock, which is just water. Electrolyzers are an an exponentially decreasing cost curve, meaning they’re getting cheaper at a pretty constant percentage rate every year. That’s really great, that’s something we’ve seen with solar and batteries, and those learning curves have proven to be absolutely transformational for solar and batteries, and have completely transformed the climate discussion. The third green technology that we see on this similar curve seems to be hydrogen.

So, an important thing: what do we use hydrogen for? There are a lot of ideas, but I think the most promising idea is long-term seasonal storage for power plants. You have a power plant, the power plant draws in some water. Wastewater, seawater, I don’t know. You draw in some water, and you use some power during the peak times, when the sun’s shining, the wind’s blowing, whatever, and people aren’t using all the electricity. You could charge a battery, or smelt some aluminum. You can also produce hydrogen, and store it locally in places where it’s much harder to leak because you’re not transporting it around. You really cut down on the storage costs and the storage losses by storing it locally. And then you can store it all the way up until winter, and winter you just burn it for energy. It’s not very difficult to burn hydrogen for energy. [Burning hydrogen does not produce CO2, methane, or other long-lived greenhouse gases, just water vapor1].

And so long-term storage I think is an important thing. You can have plants that both produce energy and do heat-intensive processes on site. Where when the sun is shining and the wind is blowing and electricity is cheap, you produce hydrogen and then you pretty much immediately burn it to provide heat for chemical processes. Decarbonizing chemical processes is sort of the boring, grubby, understudied underbelly of decarbonization, because people just don’t think about it. They think about consumer stuff, right? They think about the electricity in your house and the gasoline in your car. They don’t think so much about industry burning natural gas as a way of providing process heat for all these chemical processes that we do. But that’s important, quantitatively it’s pretty important. We need to do something about it, and this is an opportunity to that.

Hydrogen cars aren’t going to work, we know that. Transporting hydrogen around is very difficult, although some people are working on transporting it around in the form of methane or ammonia. But then converting it to those forms involves further efficiency losses. I think the uses where hydrogen doesn’t have to be transported will be the most important things. Not cars, not transportation, things where you produce it and either use it immediately or store it on site.

Can you tell me about the innovative concept "friendshoring" that you’ve written about, and what the Biden Administration should do to move this forward?

The name “friendshoring” I heard from Janet Yellen, the Secretary of the Treasury. I didn’t invent this, this is just something I picked up on and talked about a lot.

If we want to be leader of a coalition, we can’t go it alone. There is definitely a Trumpist “America alone” element to Biden’s trade policy that needs to be excised immediately. And Brian Deese [Biden’s Director of the National Economic Council] needs to listen to this. There are occasionally reasons why we want to move economic activity from an allied country to the United States. For example, having all of the world’s top-end chip production in Taiwan is not good. Even forgetting about China, it’s not good because of earthquakes. Taiwan is in an earthquake zone. We don’t want a sudden chip crunch because of earthquakes. So we need to move some of that out of Taiwan, but it doesn’t need to be America, it could be Canada or anywhere. So there are a few cases like that where we need to diversify if we can, simply to avoid a catastrophe. But in general, the idea that we need to produce stuff in America rather than an allied country is a bad idea. We want to get our factories out of China. And that means we need to get them into India, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Taiwan, and a lot of places. And America, of course.

The purpose of trade wars and tariffs is really to hurt the other country. You take losses to hurt the other country. We did tariffs against China under Trump, those hurt our consumers and didn’t help our producers, but they hurt China more. That’s why Biden kept the tariffs on China. Biden sensibly took away the tariffs on Mexico, Japan, Europe, all those things. Some had already been taken away. But he basically took away tariffs on everybody but China, and that was great because there’s no reason to hurt our allies, that just makes us a rogue state instead of the leader of a global coalition. Instead, friendshoring means that we need to treat economic growth and industry growth in our allied countries as a win for us. If India builds iPhone factories, that is a win for America, if it’s being built in India instead of China. If Vietnam builds iPhones in Vietnam instead of China, that’s a win for America, Japan, and Europe, a win for everybody except the authoritarian bloc, who we don’t want to make stuff. Yeah, it’s a bit of a Cold War mentality! But the Cold War was also a golden age of limited internationalism. America was actually much more protectionist in those days. The reason we could persuade ourselves to support the economic development of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Germany, France, and other European countries was because it was necessary to build up those countries as a bulwark against the Soviet Union. We need to bring that thinking back. We need to build up not just those countries again, but also India, Vietnam, Indonesia, countries like this that want to resist domination by their powerful neighbor.

What is your horizon scan on some of the nascent energy abundance projects in America? I try to do this in my newsletter. What do you think of the big proposed lithium project in California’s Salton Sea, using geothermal energy to extract lithium from brines? Here’s a great article on it.

That’s so good, more of that please. Geothermal is important, it’s not a whole solution to renewable energy because you can’t do it everywhere. [This may change in the near future with new technology-check out The Weekly Anthropocene’s deep dive!]. Geothermal availability is different by place, but as Iceland has shown, it’s extremely efficient in places where you have heat close to the surface. And so let’s do more of that. Locating these metal processing facilities right next to those sources of cheap, consistently available energy, that’s just a no-brainer. And again, we’ve just got to get past NEPA.

Engineering is amazing. And one thing about modern America is that we have been removed from engineering. We have a special caste of people who do engineering instead of engineering being a broadly participatory thing that everybody knows how to do. And part of that is the offshoring of manufacturing, part of that is the shift from hardware, changes to our education system, I could go on all day. We need to get back to being closer to engineering and having everyone know a bit of engineering. Just knowing how to fix your car is a little bit of engineering. I don’t have an answer for this yet, but we need some way for people to get closer to engineering as a participatory activity, so people understand just how cool it is that we can actually do all this stuff. And how important it is that we retain the capability to do a lot of this stuff.

We are part of nature. Our technology is part of nature. The degrowth people who imagine that humanity is a tumor on nature need to rethink their approach. Humanity certainly can act as a tumor, destroying natural habitats. But we shouldn’t, and technology gives us the ability to coexist with nature without acting like a tumor.

“Technology gives us the ability to coexist with nature without acting like a tumor.”

-Noah Smith

What are your thoughts on the future in general? You’ve written a lot about the future, science fiction2, and potential science realities: about a potential new American century, the post-cyberpunk-ness of the world we live in today, the mind-boggling possibilities of generative AI (as you put it, the "third magic"), and more. How does all of that fit together in your mind when you’re trying to think about what 2050 or 2070 looks like?

I think that the combination of energy portability and AI will mean that robots will be a reality in a way that they weren’t before. Our most important robots are now either industrial robots in factories or Roombas. Those are the robots we use. Robots are going to become more important to our lives. They’re not going to be a humanoid android walking about like in an Isaac Asimov book, that’s not what robots are going to look like. they’ll look like little spiders, little dogs, blah blah blah. Autonomous drones are going to transform warfare. Warfare in 10 to 20 years will just be us siccing our robots on their robots, and on their people, and vice versa. The world will be populated by a lot of robots. I think that’s an important trend.

A second important trend that I think will define the future is Africa, if you look at population projections. The number of kids in Africa is also declining, but it started declining much later than in other regions. Other regions, kids per person fertility rate started declining like in the 70s and has been declining since. Helped by rapid economic growth, which tends to make fertility rates fall. In Africa, fertility rates are now declining, they’re declining at a decent clip, but they started much later, in the 2000s or even just right now. So in other words, all the young people are gonna live in Africa seventy years from now. That’s where the young people are going to be. They’re not going to be in China, India, Latin America, the United States-unless we have more immigration-the Middle East, or Southeast Asia. They’re going to be in Africa. We must make a world where Africa flourishes, otherwise the world has no future at all. And so that’s a thing that people don’t really think about, but it’s really easy to see from these easy to predict trends. I think UN population projections have overstated future African population growth, but even so, it’s going to be absolutely huge.

Climate change, we’re not going to beat it. We’re going to dramatically limit the impact of it, but it will be a warmer and more environmentally volatile world for the rest of this century. And will be until we get carbon removal technology to undo some of the damage we’ve done. And even then, some damage will remain to ecosystems, shifting of biomes and things like that. We will eventually fix climate change but right now all we can do is kind of slow and ameliorate it. We are definitely going to get to 1.5°C of warming, that is a thing that will happen. Bet on it. Whether we get to 2°C depends on our current policies. I think we have a decent chance of holding warming below 2°C, but 2°C is probably a reasonable expectation of where we will eventually get. And if you look at the estimated impacts of what a warming of 2°C over preindustrial conditions looks like, it is quite different. There’s going to be a lot of severe stuff. Disasters, flooding, crop changes, all kinds of things that we don’t like. A few areas will be uninhabitable, some areas in the desert will be uninhabitable. A lot of places, they’ll be more subject to disasters like the recent Pakistan floods. So that’s going to happen, and that’s going to create danger and risk for much of the world. Even if, as I think we will, even if we act now in a big way to limit change change. So I think those are some important factors.

Another factor is that technology is shortly going to be able to change the basic nature of humanity more directly than we’ve been able to do in the past. In the past, you could take a person and give them a machine, take a person and give them a computer, augment them with all these things. But we haven’t done a heck of a lot yet to change how a human being works. And I think that with things like brain implants, the cybernetics people talk about, we’ll be able to give blind people sight, deaf people hearing, people with limb amputations we’ll be able to give robotic limbs that can actually feel-which we just invented, by the way. We’ll be able to do all these things. But the most important thing will be changing our brains and our genes, with brain implants and genetic modifications. Things are gonna get weird. Humans are going to be different. The era of transhumanism is upon us. We’re just gonna have to deal with that and try to shape that future, because it won’t be stopped and it can’t be ignored.

Wow. That was amazing. So the last question that I always try to ask is: what question should I have asked that I didn’t ask? What question do you want to answer that I didn’t get around to asking?

The question you should have asked me is, why do rabbits make great pets? (laughs).

Okay, Noah. Why do rabbits make great pets?

Well, there’s two big misconceptions about rabbits. The first is that rabbits cannot be litter trained. In fact, it’s easier to litter train a rabbit than a cat. All you do is you put the litter box next to the hay feeder and then they litter train themselves pretty much instantaneously. The second misconception about rabbits is that they’re not affection. They are extremely affectionate, and cuddly, and they’re great. They love having their ears petted. They’re basically vegan cats. Rabbits are just cuddly and fun. They don’t live as long as cats, but they’re quiet. They’re friendly, sweet creatures. People should definitely take a look at rabbits.

Thank you so much!

Thank you.

Which is technically also a greenhouse gas in that it traps heat, but water vapor falls out of the atmosphere as precipitation really quickly (instead of staying up there for decades like methane or centuries like CO2), so it’s not a problem and doesn’t contribute to climate change.

“If India builds iPhone factories, that is a win for America”

Really wondering how many of these comments are gonna come back to bite you in a few years, Modi is taking India down a very dangerous road and assuming that India is a long term strategic partner of the democracy Coalition is not a bet I would feel comfortable making right now

“Oh yeah, they go together like peanut butter and jelly. “

So this means they don’t fit together at all but Americans weirdly think that they do? 😀