Akshat Rathi is the Senior Reporter for Climate at Bloomberg News, where he leads the Zero newsletter and podcast. He holds a Ph.D. in organic chemistry from Oxford, and recently published his acclaimed first book, Climate Capitalism (reviewed by this newsletter). Prospect magazine named him one of the world’s 25 Top Thinkers for 2025.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Dr. Rathi’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

This interview is syndicated by both The Weekly Anthropocene and Your Daily Dose of Climate Hope.

You’ve written about how market forces are now leading the clean energy transition, with solar providing the cheapest electricity in history. Can you talk more about that interplay between government support for R&D and eventual market-driven global shifts?

I think the way to think about this, the one that most makes sense, is that most technologies — not all — get started with government support. Through research in universities and national labs, or sometimes company R&D. But that company R&D, things like Bell Labs in the U.S. where there was research dollars of real significant amounts being invested in speculative ideas, required a level of investment upfront which typically came from government. And then sustained investments to try and make it commercial, which came from the private sector.

So solar and wind and renewable energy in general required that [government investment] initially, because those are technologies that held the promise to be cheaper in the long run, but needed to become cheaper through early development, through early deployment. That was where, the involvement of governments in research and then early-stage deployment was crucial. But in many parts of the world, that is not necessary now. That’s true for solar, wind, batteries, and electric cars, in many cases, but it's not yet true for many other types of technologies that we do need in the transition, which will still require government support.

So, I think the narrative shouldn't be that it is only through government support that these technologies will do what is needed to tackle climate change. It is through early support from governments, and then eventually it is market forces that will actually really scale them.

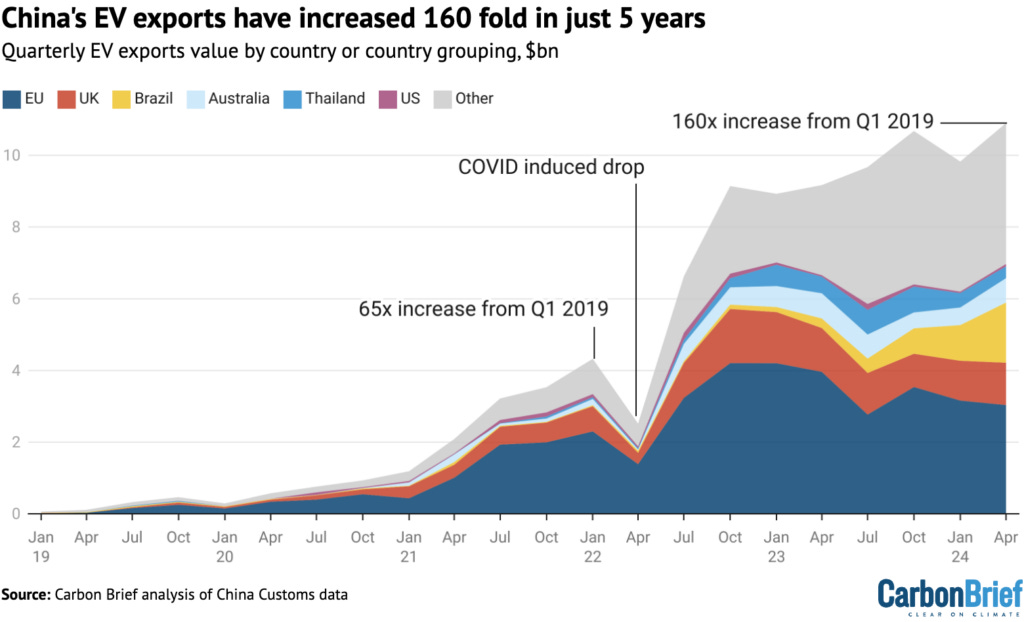

One really paradigmatic example that you shared about that was the story of how China, thanks in large part to one man, Wan Gang, has invested so much in R&D of batteries and electric cars that they’ve now built world-leading companies like CATL and BYD. So those are market-leading colossi, built thanks to that early government support. Could you share a summary of how that happened? How did we get from one Chinese guy being interested in this stuff to the huge global cleantech colossus companies that China has today?

Wan Gang was born in China, trained as an auto engineer, but really got his professional credentials in Germany, working for Audi. And German auto engineering for the past century — until this decade — was among the leading places to make cars. Chinese leadership often visited Germany to understand, what can we learn from Germany and how can we improve our own auto manufacturing? And in that process, they met with Wan Gang, who was at Audi at the time. They had this conversation about, what is the future of 21st century auto manufacturing? [This happened c. 2000.]

Wan Gang made the case that it is much better to move away from fossil fuels, because the internal combustion engine has sort of peaked in its ability to give more. There are definitely still improvements to be made, but those improvements are very small and they'll take a long time and we won't be able to catch up with the Germans. So that was one reason: if you want technology leadership it is better to try a different technology [than the incumbent].

The second reason was, we don’t have much oil in China. We continue to import a lot, and we will import more as more combustion engine cars are sold. Wouldn't it be better if we tried to rely on something that we have access to domestically? Which would be electricity.

The final reason was of course that he anticipated, as he had seen in other places, that if you start to burn fossil fuels in cars at a real large scale you'll see air pollution, and pretty terrible air pollution given the density of population in China. That came true.

So all those three reasons were real important reasons for the Chinese leadership to go, yes, this makes sense. We should invest in this technology and see where we can go with it. So the government set a direction for investing in batteries and in electric car manufacturing initially, and created these government incentives both for manufacturing but also for purchasing these cars.

But eventually, the vast majority of money that got invested in that [Chinese EV and battery] industry, and why it's become this global behemoth and a global leader, is because of private industry. People like Warren Buffett invested in BYD.

So it is a good poster case for what can be achieved if governments have a long-term vision for a technology and have precise amounts of support given to it. And then letting competitive private industry actually take forth what types of technology within that big broad set would progress, and what types of products will be purchased by people. That combination seemed to have worked in China's case. And it is not an accident because it is also something that other places like the United States have done, broadly classed as industrial strategy. It's just that China has done that for green technologies and done that pretty well.

Absolutely.

There's been a lot of growth of renewable energy in India recently. Your book actually directly inspired me to go visit and report on the Pavagada solar farm when I was in India earlier this year. As you know, the Modi government and others are really interested in developing independent Indian cleantech manufacturing. What do you think are the odds that India can economically develop its own, solar, wind, battery, and EV manufacturing given that China already has such a lead in these fields?

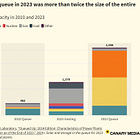

I think it’s hard to generalize for all technologies. Solar already has a manufacturing capacity of a terawatt [1,000 gigawatts, or 1 million megawatts] per year. In most projections, solar doesn’t need to be more than a terawatt per year to reach net zero.

To be clear, what Akshat is saying here is that the world (mostly China) now manufactures more than enough solar panels per year to transition the entire world to a net-zero emissions economy over the next few decades!

And so perhaps building solar manufacturing, not just India, but as the U.S. is attempting and as Europe wants to attempt, are going to be attempts that will be done out of national security concerns, not out of an economic energy transition concern. It is up to governments how much they would like to invest in that industry as part of national security, rather than as part of an economic motive.

But in almost all other technologies…wind is one where there's already a distributed nature to it. Wind turbine blades are really big, and you want local manufacturing. Even though the industry is at scale, it is not concentrated in China alone. There’s room for other players to grow. Things like lithium-ion batteries, electric cars, they are at a very early stage of development, and there's plenty of room for other countries to get involved.

The total number of cars in the world that are electric, just as a fleet [i.e. all existing cars, not new sales per year], is only about 3%. There's 97 percent of the market still to play for. Most car manufacturing does happen domestically, most countries make cars in their own countries. That's true of American cars, that's true of German cars, that's true of Indian cars. There’s plenty of room for large economies to build their own battery and EV manufacturing.

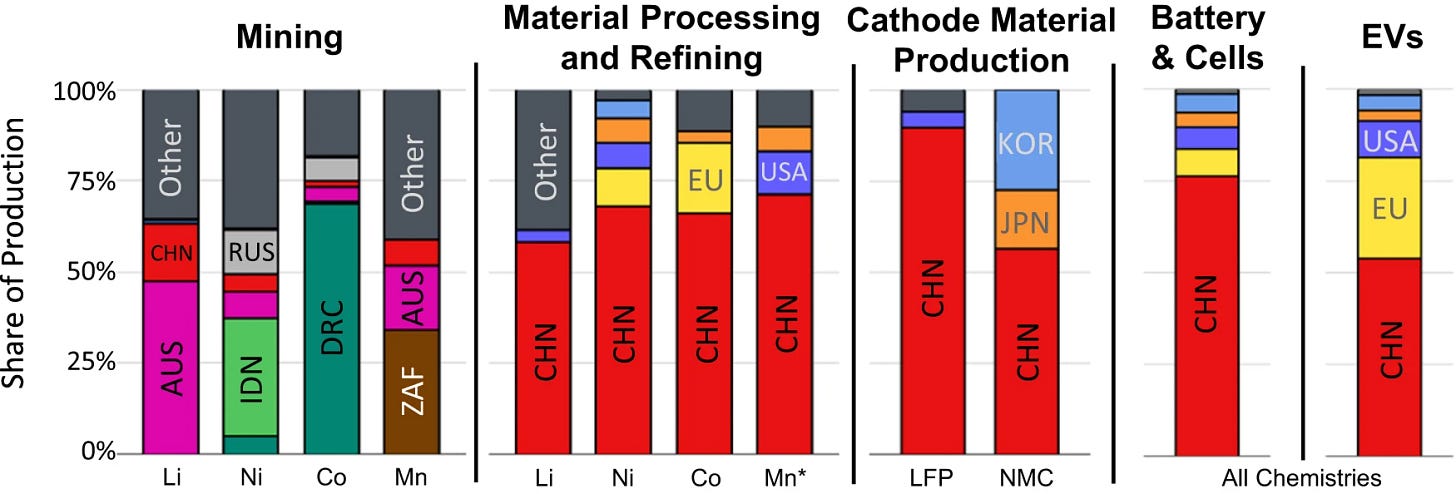

But if you take one step back, the metals that go into batteries are currently very Chinese-dominated. And trying to break that is seen by many countries as a national security demand, right? These metals are not just needed for batteries. They're also needed for semiconductor manufacturing. They're needed in electronics of all sorts.

That’s why you’re seeing, in the U.S., EU, and India, bills tied to local recycling, manufacturing, mining, and refining of these minerals, which would incentivize more of that mining or refining to come onshore. How fast that will happen is a question, but there's clearly a motivation from governments to do it.

So, you know, it's not a uniform answer. In some cases, it's much better to let China do it, like in solar. But in other cases, if governments can see reasonably that that is an industry they want from a national security perspective, or they see an economic opportunity in the future, then they can still invest in it and do so systematically and get to a point where they do have a domestic industry.

What do you think, basically, are the odds of actually pulling this off? Especially given the the second Trump presidency, that might be focusing on trying to extend the life of America's fossil fuel industry rather than becoming competitive on critical minerals and stuff. What do you think are the prospects for India, the EU, and America to build an independent cleantech manufacturing base to match China's? Do you think that in 20 years or 15 years or 10 years, China will continue to be the providing the vast majority of battery critical minerals refining and electric vehicle and solar panel manufacturing in the world? Or do you think that America and India and the EU will successfully stand up their more local versions of these industries?

I don’t know. It’s hard for me to make any prediction of that kind. What I do know is that these industries are needed not just from a climate perspective, not just from a carbon emissions reduction perspective. There are many other motivations for these technologies to be within your territories. You could look at those other motivations as reasons why they might still be supported even though they are quote-unquote “climate technologies.”

One thing you can see in the U.S. is a bipartisan desire to try and reduce U.S. dependence on China. So critical metals mining and refining might get support even through a Trump presidency. But whether that turns into a sustainable economic enterprise is hard to say right now. Given the trends, it’s hard to see it happening without there being persistent support from government. In Europe and India, there is, at least, some consistency in government thinking. In the US, it tends to swing left and right quite a bit these days, so businesses will find it harder to think about a long-term trajectory in the U.S.

So we've been talking so far about some of the major existing clean energy technologies. Who do you think are the current leaders in some of the emerging technologies? Like, decarbonizing heavy industries like steel and cement? I've read about some exciting startups. Electric arc furnaces have become more popular in China. There's hydrogen-burning steel making in Sweden. There's the startup Boston Metal in the United States, they have their own really cool green steel making method. And I actually just read that China claims to have developed a new “flash” iron making technique that should be another lower carbon way to make steel. The Biden-Harris administration's Department of Energy has given some substantial grants to early American startups working in these spaces.

Who do you think is leading in this, the next phase, of decarbonizing the harder to abate industries? What governments do you think have more sustainable support for that? Where do you think the economics are pulling for that kind of technology to emerge?

There is no clear winner yet. You're right that the things that have been commercialized have been electric arc furnaces. It's an old technology, recycling of steel using electric arc furnaces. But now you can actually use electric arc furnaces to make virgin steel as well, which is something that is getting a boost.

Yes, there is one plant in the world that uses hydrogen, in Sweden.

There are some attempts at using just electricity to do electrolysis. It's a sweet spot for technology nerds to be able to explore what works and what doesn't work.

No single technology has emerged as the clear choice for decarbonizing heavy industry, unlike the clear choice of solar photovoltaics for power generation. So there's plenty of room to play for it. Again, decarbonization is definitely the end goal for these technologies. You want all sorts of things to not have any carbon attached to them. But the thing that will make them economic is if they're able to do so with lower energy input. In hydrogen, for example, the energy input is actually higher than it is if you're using coal, whereas in electrolysis, it could be lower. You could imagine a future where decarbonization is the outcome that people seek, but it is going to be cheaper if you have lower energy input. That's one place to look out for when you're looking at these new emerging technologies, not just the decarbonization potential, but also how much energy they use and thus how much they'll cost, which will make them economically attractive to actually scale.

I’ve been reading that in countries with really abundant open, sunny land, like Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Australia, and even Namibia, some have proposed to build a whole bunch of solar photovoltaics to have really cheap electricity for industrial processes, and then export the resulting products. These strategies to have places with huge amounts of renewables so electricity is really cheap so you can get a head start on these electricity-powered industrialization processes: will that work, do you think? Or will decarbonizing heavy industry end up being more like solar, where it's more dispersed and whatever the right technology is, that'll kind of work anywhere in the world?

Well, electricity is fundamentally the most important, exciting form of energy that we have. It is interconvertible into any other form of energy as you want, and it does so very efficiently. You can get from electricity to motion much more efficiently than you can from heat to motion.

Same for heat. Electric heat pumps actually produce four units of heat for every unit of electricity, whereas when you are burning fossil fuels you only get one unit of heat for every unit of fossil fuel you're burning.

So electricity itself is a form of energy that's going to be used more and more all around the world, and our reliance on electricity will grow because of the benefits it brings in, just fundamentals.

However, electricity does have its downsides. The reason why it hasn't become the only source we are using so far is because in the past, it was hard to generate in all the places we wanted. Because distributed energy from solar and wind was very expensive. And now it's cheaper! So that one challenge has been overcome.

The second, which hasn't yet been overcome, is storage and distribution. Those are still expensive and challenging. And yes, storage prices are coming down, but they need to come down a lot before we can say we have solved the storage challenge. Transmission isn't so much about the cost of building, although there is that cost. It's really about just the distances that would need to be moved [i.e. building long-distance power lines]. Government reforms or public acceptance for how much they can be moved is more of a question than the cost.

So going back to your point, which is, would countries that are blessed with renewable resources be able to really tap into the advantages they bring to those countries? The answer is yes, if they so wish. Because if you look at the history of energy, the countries that have cheap access to energy are able to then convert that into productive outcomes for those countries. Perhaps that is through exporting, as has been the case in the Middle East where petrostates have used their access to cheap oil and gas to become big hubs for exporting that oil and gas to other countries. With electricity, it's harder to extract it, say, in Namibia and then use it in Germany, because transport is much more expensive. But what Namibia could be doing is extracting that solar energy, converting it into something that the world wants — that might be iron or steel using electrolysis — and then using that to become the export hub that it needs to be.

So there is certainly a case for all the countries that have higher potential for renewable energy than others to actually tap into it. And we will see them doing it. Whether they do it systematically with the kind of support that they need, with the financing coming through, is the real question, not whether they will do it or not.

Fascinating.

There's a huge amount of excitement about nuclear, especially in the U.S. And my personal take on that is that it's nice, but minor. I mean, nuclear is much lower emissions than fossil fuels. It’s much safer that its detractors say. But it feels fundamentally like a sideshow. You see so much excitement around new reactor designs, like TerraPower in Wyoming or Kairos in Tennessee, and then you read that they’re hoping to produce, like, 500 megawatts by the 2040s or something, whereas China just inaugurated 2,000 megawatts in this month’s new solar farm in the desert. Nuclear, it's always technologically interesting, and quite safe and low-carbon, but it's always way more expensive, takes way longer, and produces way less power than the rapid growth of solar farms. So do you think there's any future for nuclear at all or do you think it'll fundamentally just stay a side player?

Well, it's an interesting one. I feel like the talk of nuclear has been around for a lot longer than outcomes. And only in recent months, I would say, not even years, have we started to see some level of outcome outside of China. China is also the place that is building the most nuclear power plants in the world. It's the only place where multiple reactors are being built sometimes in the same year, which is not the case anywhere else in the world.

So outside of China, there hadn't been really any outcome based on all the talk around nuclear. Now you're starting to see that with some of the small modular reactors getting into the hundreds of millions of dollars from tech companies, not just governments. Nice to finally see some outcome to all that talk.

But yeah, you're right. In the sheer amount of potential that nuclear has and will deliver, that's just going to be a big gap, right? If you really wanted to build nuclear like the way France built it in the 70s or China built it in the 2010s and 2020s, you have to make a serious commitment towards it at a government level and build many, many plants [enabling modular parts, economies of scale, and a higher learning rate, among other factors], have the engineering training capacity to build it, have a real 21st century plan to deal with the nuclear waste that would be generated. You don't see that. So there is a whole structural conversation that impedes its potential from being able to reach the sort of cost or just sheer capacity that it can.

And that's okay. I feel like in terms of electricity generation, it’s good to have different sources of energy generated. Ideally, all of them decarbonized. It could be geothermal, it could be nuclear, it could be, you know, solar thermal. It really is good to have a diversity in technology, but you are also right that you should be realistic about what will get built at scale.

That really segues perfectly into my next question: enhanced geothermal.

I'm sure you follow the startups in this field in the U.S., like Fervo Energy and Sage Geosystems. They are building functional clean energy power plants with relatively much less investment than a new nuclear reactor, and they're doing it with something pretty close to off-the-shelf parts from the oil and gas industry. I'm really excited about this for several reasons. It seems to me like enhanced geothermal might have solar photovoltaics-like world-changing growth potential in a way that nuclear does not. And I'm really hoping it does, because it would be great to have that 24-7 baseload energy.

What are your thoughts on the potential of enhanced geothermal as both baseload clean power and a ready-made "off-ramp" from fossil fuels due to using similar drilling rigs?

It’s very exciting to see, there’s no doubt about it. But I think we also need to be realistic. The only place where you're really seeing advanced geothermal takeoff is in the U.S., in the place where there is fracking happening for oil and gas at scale, where you have both the technology but also the government permissions to be able to do it at scale. So you're able to use those engineers. You know, the founder of Fervo, Tim Latimer, used to work in the oil and gas industry, and has a ton of engineers from the oil and gas industry coming and joining him. The rest of the world hasn't really tapped into shale [fracking], for many reasons. Some don't have the capacity, some don't want to do it, and technology transfers haven't happened in those places yet. So I would be excited for the true potential of geothermal only if I see that stuff outside the U.S. starting to scale, which it isn't currently. But, you know, even if it doesn't happen outside the U.S., if it does happen in the U.S. and happens at scale, that's still a pretty good thing!

What about in Kenya? Kenya gets a really large chunk of its energy from geothermal now. Of course, that's sort of old-fashioned geothermal, that's not enhanced geothermal where you inject your own water underground.

Correct. There's conventional geothermal potential that exists in Kenya and Iceland and in Asia and a bunch of countries, and that can still be tapped. That would be good to be tapped. But you were talking about enhanced geothermal, that I haven't seen outside the U.S.

What I’m saying is, do you think that countries with a solid conventional geothermal industry will be able to use some of that expertise and engineering to get a head start on enhanced geothermal outside the U.S. in the near future?

I'm not sure, because I don't know whether the geology supports the fracking-style technology in those places. Also, I'm not sure whether the government regulations exist to be able to allow that to happen, or the technology and the expertise for engineers in those countries to do it. So until I see a Fervo plant somewhere else outside of America, I am not sure that potential is realized.

But yeah, it is certainly one that is very exciting, and I'm keen to follow and see where that lands!

Yeah, me too!

You recently had a famous one-on-one discussion with Exxon CEO Darren Woods at the climate talks, about the future of fossil fuel incumbents. During your interview, Woods rather surprisingly said that Exxon recommends that President Trump stay in the Paris Agreement and keep Biden-era climate legislation.

What do you think are the near-term future moves that will likely be made by the major fossil fuel incumbents? Because on one side, obviously, they're trying to ramp up production, burn as much fossil fuel as possible while there’s still a big demand. But sometimes you see glimmers of alternatives from even these infamous companies; I recently read that Exxon made an investment in a lithium mining project in Arkansas to supply lithium to an electric vehicle battery factory in Tennessee.

So, how would you summarize your takeaways from that interview?

I would say that there is no reason to expect a U-turn in a company like Exxon’s strategy just because they came up on a climate podcast and appeared at a climate conference. To me, it was an opportunity, and I would take that opportunity with any oil and gas company CEO anywhere in the world, to be able to get them to answer questions that so many people have but they rarely ever answer. That is what I did with my interview. I wanted to ask a set of questions which I was able to ask without there being any restrictions on what questions I asked.

And it gives you an insight into the thinking that the company has, which is that it is an interesting choice to make to come to a climate meeting after the U.S. election chose to have Trump be the next president. It was interesting to me that the CEO of an oil company that has a history of opposing climate action and sowing doubt about climate science you know comes to a climate conference and says, “Actually the U.S should not be pulling out of the Paris Agreement, because it is good for U.S. industry to be a part of the Paris Agreement.”

It tells you something about the moment that we are in. Which is that despite the talk of Trump or other right-wing parties to move away from climate action, there is a fundamental motivation that comes perhaps not from the climate space but from the space of the future, which is “This is where money will be made.” Climate solutions are where money will be made, eventually. That is why companies are so keen on making sure that they don't end up on the wrong side of history betting on technologies that are not going to have much of a future, and being on the right side of history on betting on technologies that will provide for a longer term return.

That's how I would see that interview. I wouldn't see it as a sign that Exxon suddenly becomes the lithium supplier of the world or Exxon suddenly stops extracting oil and gas and starts becoming a carbon capture hub. I don't think either of those things happen. What Exxon is saying is “Look, we showed up at a climate conference! We have shareholders who care about climate change, we have a portfolio of things we can show them which we are doing because we think those things will make money, maybe in the future a lot. But we are also doing the things that make us money right now. Which is, extract oil and gas, and a lot of it.” Exxon is the only oil major in the West that is increasing its capital expenditure on oil and gas extraction, no other oil company is doing that. Take Exxon for what it is, rather than construct a narrative from the fact that they ended up on a climate podcast.

Yeah, definitely. I'm not trying to do apologetics for Exxon! Hell no. I'm just trying to figure it out. What did you feel during the interview?

The engagement was genuine, which is really good to see. They were interested in answering the questions. They were open to it, they had their own take on it. Which I expected they would have, but that they are open to scrutiny of this level, that is very welcome.

It’s really striking to me that freaking ExxonMobil, one of the world's largest fossil fuel companies, is is in favor of staying in the Paris Agreement and a bunch of Republican legislators still want to go out. And there are other similar cases, like at the state level in Texas. [Extremist anti-renewables bills only narrowly failed to pass the Texas state legislature in 2023, with disaster avoided mostly thanks to business interests, including dozens of Chambers of Commerce, strongly lobbying to protect clean energy].

It seems to me that there’s now an increasing list of issues where fossil fuel companies, business interests more broadly, and climate advocates are sometimes on the same side, often just because of the manifest economic value of clean energy-related stuff, and the more extreme sort of anti-climate action people in politics are further opposed to climate action than the actual fossil fuel companies. I think Robinson Meyer called it “carbonism,” the ideology that burning fossil fuels is just a good thing for its own sake, regardless of the economics. Have you noticed that?

Well, I think that the number of people who are, as you say, ideologically driven to burning fossil fuels regardless of the economics, is a small, small number. Yes, some of them sometimes end up in powerful places, but the reason why we even talk about them, just as we did talk about climate deniers, is they are a loud bunch and they can try and make themselves heard in ways that others don't.

Any ideological extent of wanting to produce fossil fuels against the economics of it will have limits, and hard limits in some places. That ideology will only go so far. To me, the way to think about this is, rather than focusing on the people with those ideologies, you have to think about it in a bigger picture. More than 70% of all oil and gas capacity reserves today isn't in the hands of public companies like ExxonMobil or BP or Shell. It's in the hand of national oil companies. It's in the hands of the sovereign states which own these companies. So to really be able to fight fossil fuels, to be able to put them in the place that they really should be on the economics today, you don't just have to face up to the small ideological bunch who want to burn fossil fuels, but you have to face up to the much larger cohort of sovereign states who have access to these fossil fuels and who would burn it because it is still economic to be able to just extract it at the level that Saudi Arabia or UAE can and export it to a country that still needs it.

So, you really want to make those countries realize that it's not going to be economic for very long. You can start to see some of that come together in things like the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty that has been signed by nearly 20 countries now, including Colombia, which is a sizable fossil fuel producer for coal and oil. These countries are looking towards a future where they do not want to extract the fossil fuels that they have in their own countries and would much rather have either the world pay them to not burn those fossil fuels or pay them to help to move away from the consumption of fossil fuels. And that to me is a much bigger fight and a much bigger challenge, and if you find solutions a much bigger outcome on climate, than really focusing on the fringe of fossil fuel ideologies.

Interesting.

So to switch sectors for a moment, I know this isn't quite your main focus, but what are your thoughts on the most immediately promising avenues for lowering agricultural emissions? There's been a whole bunch of interesting ideas I've read about, like climate-resilient crops, methane-reducing vaccines for cattle, commercialized methane-eating microorganisms, electro-agriculture, and decentralized clean ammonia production. Even something relatively simple like precision drone fertilizer application can just prevent a lot of fertilizer runoff and some of the the direct off-gassing of greenhouse gases from some of the nitrogen-based fertilizers. There's, of course, the whole realm of genetic engineering. There's a whole bunch of different stuff going in agriculture, but it all still feels very early to me. Do you have any perspectives on what the most promising avenues for decarbonizing agriculture are?

Yes, it's certainly a very fruitful area of technology improvements and growth and development. And certainly under-appreciated, under-talked about. Because agriculture is not sexy, right? You’re not coming up with some new gadget like an EV, just producing the same crop with a lower carbon footprint. But I think it is crucial to actually do the work in addressing and improving on these technologies, because agriculture is at the forefront of climate impacts. It's the place where you are starting to see real decreases in productivity for many major commodities. Cocoa and coffee prices in recent years have been crazy high, olive prices were crazy high, and the sheer number of people who are involved in the agriculture industry is huge. So it is completely under-appreciated and under-worked on.

Now, when it comes to emerging technologies, there's just one thing to realize. The ease with which you can build a solar panel in China, put it in Bratislava and still generate power is fantastic. It's not something that you can do so easily with agricultural technologies. So yes, you might be able to generate like a type of product like the microbes that can put nitrogen into the soil rather than ammonia from some synthetic fertilizers. But good luck convincing an Indian farmer to use that product, someone who has no education in climate or in science, who lives from harvest to harvest, who would rather just do what he knows has worked in the past and is not interested in your promises because those promises are nothing compared to the next meal that they need to buy. It is not as easy to transfer those technologies to the places where you will have to deploy them at scale.

I would be very interested, and this is not something I've looked at, but I'd be keen to know where are the places where large-scale agricultural solutions of all sorts — to improve productivity, to improve soil carbon — have worked not just in one rich country, but also the same technology has been working in a developing country. I think that I haven't seen yet. And so we do have a massive challenge in front of us with agriculture. It's not just about technology development, it's also about putting the technology to use, which is not going to be that simple.

Jumping around again, what do you think of the potential for huge unexpected bottom-up solar revolutions even in countries with almost no sort of government leadership on clean energy, now that we have so many cheap solar panels being made? You saw the news from Pakistan — something like a fifth or more of the entire electricity generation capacity of Pakistan was added again in imported solar panels in one year! And the government didn't even appear to be aware. It was just people buying solar panels themselves. We're getting something similar in South Africa because their grid's having trouble.

So, what are your thoughts on the "bottom-up" solar revolution of Pakistan and its potential as a model for other developing countries with low state capacity? What are the odds of a best-case scenario where we wake up ten years from now and billions of people in the global south now have solar?

The odds are very high that solar ends up in more places than people are imagining and projecting. Betting against solar, the odds are very low. Betting for solar, the odds are quite high, just because of the accessibility of the technology. It is just dead simple. These days you can buy a solar panel, plug it into your home, and use the electricity from that generation, as you can do in Germany with balcony solar. You don't even need a rooftop! That’s very exciting.

You know, solar is the ultimate form of energy. Even fossil fuel is just solar power converted through some dead plants. And so it's nice to be able to have the raw amount of power that just falls on the planet all the time!

That is spectacular! And the more I look at the solar energy statistics, the more I'm like, just how far could this go? How many of the world's problems can be solved with just escalating amounts of clean energy? There's a bunch of stuff that doesn't seem remotely economic now, but might be economic in a world with cheaper and cheaper solar, which it seems like we're going to get.

Like atmospheric hydrocarbon synthesis, “fuel from air,” synthesizing burnable hydrocarbons from the carbon in Earth’s atmosphere. Casey Handmore has a startup, Terraform, that's working on that. Theoretically, in a world with vast amounts of energy, you can, even though it takes a huge amount of energy to do, trap the carbon from the air and turn that into a fuel. We could theoretically just have an infinite loop of carbon that could replace the fossil fuels with an atmospheric carbon-derived fuel that could be burned in existing combustion engines. Do you think that we’ll ever get to a point where we have so much solar that we can do crazy high energy input things like that and have it be economic?

I mean, I think if you are thinking about what to do with the abundance of energy that we could be getting from solar, there is just a lot more that we could be doing before we get to the point where the vast majority is being deployed to make synthetic fuels.

Yeah!

There's just a lot more productive use of low cost energy that would be beneficial. Right now I would much rather have that abundance of energy being actually deployed to try and deal with energy poverty.

There's still 600 million people without access to consistent power, there are four billion people still not having access to enough energy on an annual basis. I’d much rather use that abundance to actually get people who live in the 21st century to live the kind of life that 21st century enables, before we worry about synthetic fuels. Which might be a useful thing at some point, there will be applications like intercontinental air travel.

There’s a theory that "batteries will outpace power lines" in some markets. There’s a startup called SunTrain that's proposing to literally ship batteries loaded with electricity on existing train lines, from solar farms in the desert to cities. And if this happens, it would be due to the dire need for permitting reform in developed countries - one of the last bottlenecks for cleantech, at least for mature technologies like solar. I'm sure you just saw the Manchin-Barrasso bill sadly failed in America. I wrote an article back in the summer begging Democrats to vote for it while we still had the chance, and they didn't. And now it looks like we'll get a Republican-led permitting reform bill, if at all.

Do you think there's a world, if permitting reform for power lines continues to stall, where batteries outpace power lines? Where if regulatory sclerosis makes it too hard to bid power lines, there will be an industry of just trucking or training batteries full of electricity around? Do you think that's ever going to be feasible?

I don't know. You're going to still need permitting reform for building railway lines on that level. I think permitting reform is much easier to get to. The politics of permitting reform, it’s much easier to convince people. It's much easier. It's winning politics if you get it right.

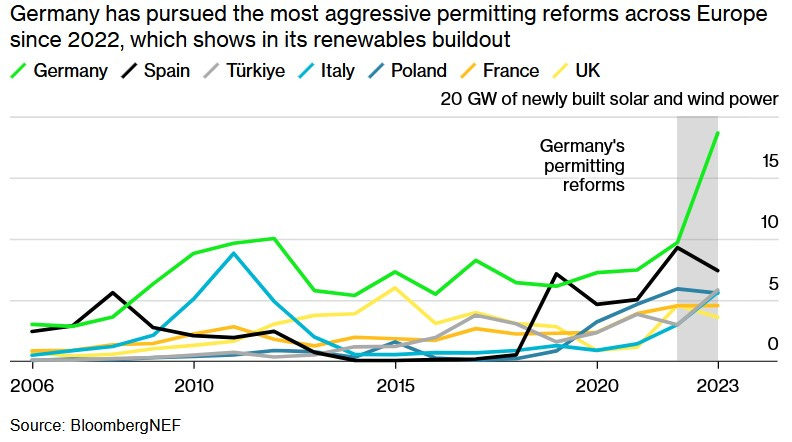

And you're starting to see some of that in Europe. Germany is a very good example. I wrote an article earlier in the summer about how, over the past two years, Germany has made a series of systematic changes in regulations that enable it to deploy vastly more solar and wind than it did two years ago, before the Ukraine crisis began. So, it's absolutely possible to do, even in a place like Germany, which is going through a political crisis of its own. Permitting reform seems to be a winning formula.

We will see more of that happening here in the UK. The UK had a very clear and ambitious plan to try to get as close to fully clean energy by 2030 as possible. It may not be able to get to carbon-free by then, but it's going to try. And that's going to require it to do permitting reform in one way or another.

I think we'll see that in the U.S. too. And maybe it doesn't come through in the form of energy, but it might come in the form of house building, which will have some benefits for clean energy. If not in this term, maybe in the next term.

But I think there's no option. It's cool to think about speculative things, like Sun Train, like the Boring Company idea that we don't need to have permitting reform to build more roads and we can just build tunnels to carry cars. But I don't know how far those go.

I’m glad you mentioned that German permitting reform case. I have two newsletters, my personal newsletter is the Weekly Anthropocene, and then I'm also doing a newsletter for a climate action organization in America called Climate Action Now. It’s called Your Daily Dose of Climate Hope, and this is actually one Daily Dose post that we did in September based on that German permitting reform article you wrote.

We’re basically asking people to use our app and use our online web form to tell Congress, “Look permitting reform means you build more clean energy, let's do permitting reform!” We're trying to be like a rapid response force accelerating the uptake of positive new ideas.

What else would you like to share in the last seven minutes? What cool technology or legislative strategy or economic factor would have we not discussed that you think more people should know about?

The larger thing that’s worth sharing is that climate change, yes it’s a problem caused by excess greenhouse gas emissions, particularly carbon dioxide. But the solution and the motivation to actually solve climate change does not have to be tied to carbon. You can find many, many other motivations that also deploy carbon reducing technologies. It could be about air pollution, it could be about competitiveness. Those other motivations are valid motivations and sometimes they are actually stronger motivations to pursue those solutions.

And I think in this time, it feels like, it’s been ten years since Paris, there’s been a right-wing turn on politics, how much progress have we made? How much progress can we make? Well, there is plenty of progress to be made even if you don't talk about carbon. So one place that I'm trying to focus my energies on is looking at electricity and electrification more broadly, because as I talked about, you know, it is the most interconvertible efficient form of energy we have.

We have certainly been increasing our share of energy consumed from electricity globally, but we are doing much more in developing countries than we are in developed countries. And that is a place where developed countries are actually losing out. They are losing out in the race to electrify. They're losing out in the race to build the technologies for electrification. And that is something that to me is an underappreciated story, that electrification of the world is actually happening faster in developing countries than in developed countries.

Fascinating. That’s the leapfrog effect, right? A lot of Asia and soon Africa is going straight from no electricity to solar panels being your first form of electricity, or an electric car being your first car, or an electric motorbike or three-wheeler being your first motorized transport. Sometimes it's even easier because you don't have something to replace, you're just adding, so you don’t have to fight the incumbents.

Yes! 100%. I mean, it's already happened, where they've gone from having no access to energy to having a smartphone that is powered by electricity, giving you the most sophisticated communication technology that there is on the planet powered by electricity right in your hands. I’ve seen that happen in India, and it’s happening all around the world. Now, if you are a person without energy, the first source of energy you use is already electricity. To me, it’s a large-scale underappreciated story. And it is the story of the West actually losing out in the race to electrification.

This is overall still really good for the world, though, right? Just from a human welfare point of view, you’d rather have this than a reverse world where like rich countries like the U.S., EU, and Japan were electrifying faster and countries like China or India were just following the well-trodden path of fossil fuels first. I mean, it's really good that we have this leapfrog effect in terms of reducing air pollution and emissions, right?

Oh, leapfrogging is fine. What developing countries are doing is fine. What I'm saying is it's a bad thing for developed countries to be losing out, because right now the U.S. is burning far too many fossil fuels for doing the same activities that it could be doing with far less energy if that energy came from electricity. And it's not like the U.S. isn't capable of generating really cheap electricity! It has, like, all the blessings of the world to be able to build as much solar, as much wind, as much geothermal, as much nuclear as it really wants. It's just not doing it. It is very complacent right now. The U.S. has become a complacent country when it comes to energy technologies, especially electrification technologies.

Do you think that if we keep enough of the Inflation Reduction Act in this upcoming legislative session, say if Republicans don't manage to wholly gut it and we still have tax credits for domestic clean tech manufacturing, do you think there's a chance that a solid U.S. clean energy industry could survive even under Trump?

Oh, I think it [American clean energy industry] survives even if the IRA is gutted, because of the economics of clean energy. But the survival of the clean energy industry is really, that's a low bar to achieve. You want it to be thriving and you want it to be competitive and you want it to be pushing the world ahead. That is not what it is doing. Fundamentally, the U.S. is not really appreciating just how far behind it is when it comes to electricity technologies.

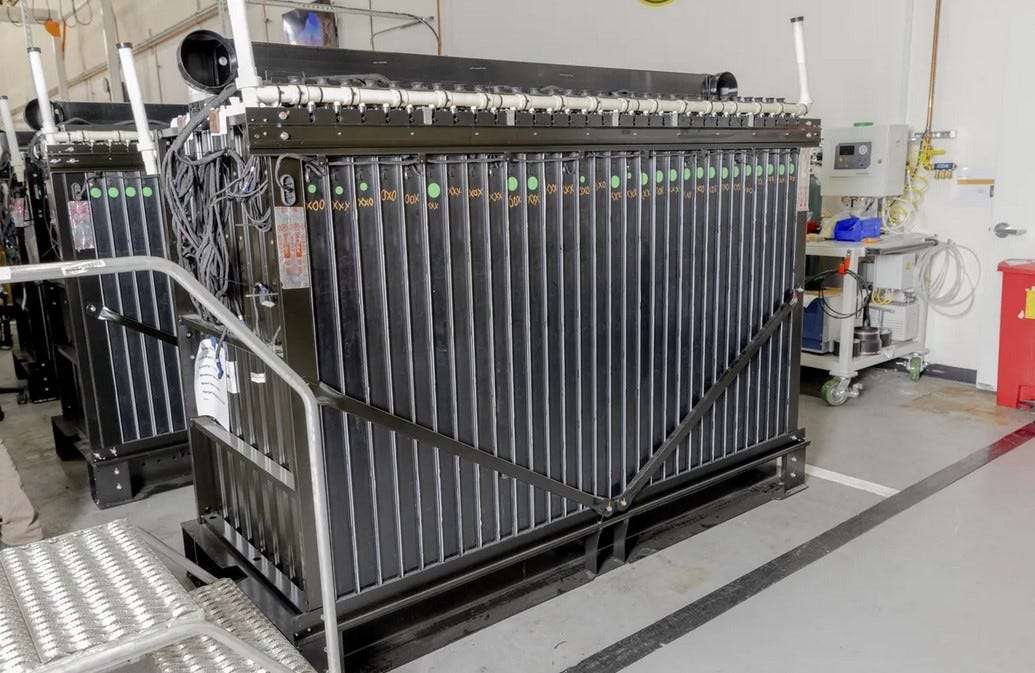

Well, that's sort of a downer note to end on for an American, but it's a message we need to hear. I am hoping that with some stuff like advanced geothermal, maybe some novel battery chemistries like Form Energy’s iron-air batteries, maybe we can find some sectors where we can still have a competitive advantage.

Here’s Akshat Rathi’s podcast episode about Form Energy batteries.

Yeah, I think that is the hope. There are places where the U.S. technology development is good, but the problem is that it doesn't always convert into deployment. Now it's starting to deploy, but will it continue to deploy at scale?

Let's imagine that someone on the smarter side in the upcoming administration, maybe Chris Wright or Doug Burgum or someone, calls you and says “Mr. Rathi, you're an energy expert. What can the U.S. do to be less far behind? What do we need to do?” What do you say?

Well, the U.S. has, as I said, all the resources it needs to be able to really grab hold of the electrification story and become the global leader, if it so chooses. It has the raw potential in wind and solar, and in metals for batteries. Access to subsurface resources for geothermal. Access to nuclear technologies and being able to deploy it. It has the engineering. It has the scientists.

What it does need to do, though, is it needs to decide to actually use them in a way that would give it a competitive edge in the world, rather than seeing the future of all world energy in fossil fuels and being beholden to the incumbents from those industries. It needs to think about where its future lies in the 21st century, and that future is certainly the one that is going to be powered by electricity. As is clear from the AI data center deployment that is happening in the U.S. now. Having access to clean, cheap, abundant energy, which the U.S. certainly can enable, is the way for the U.S. to think about the future.

Thank you so much. This has been a spectacular interview, and I have really enjoyed talking with you.

Thank you.