Book Review: Climate Capitalism by Akshat Rathi

A brilliant "first draft of history" outlining how individual researchers, companies, and governments around the world have started winning the fight to power human civilization with clean energy

Climate Capitalism, by Oxford-trained chemist and veteran Bloomberg Green reporter Akshat Rathi, is fairly brief, with twelve short chapters packed into just over 200 pages. Despite this, it’s the most up-to-date and comprehensive book-length treatment of the 2010s-2020s global clean energy revolution that The Weekly Anthropocene has yet seen.

When I was about halfway through reading Climate Capitalism, I realized that this book’s genre is “superhero team-up movie,” and one of the better ones at that. You can practically hear the different musical themes for each chapter’s main character and see the montage as their work progresses to world-changing levels. It’s Avengers: Climate Change, with a colorful cast of characters from all over the world.

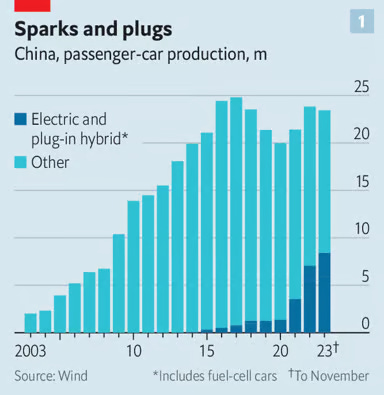

There are chapters on the slow, subtle, years-long effort to convince China’s bureaucracy to invest in battery and EV manufacturing resulting in the launch of titans like CATL and BYD, with world-transforming results.

There’s on-the-ground reporting of how Indian farmers can benefit from leasing their land for solar power, making money from clean electrons as drought and groundwater shortages make it harder for small proprietors make money growing crops.

There’s a detailed treatment of how Denmark kicked off the modern wind energy industry in response to the oil shock of the 1970s, culminating in the epic metamorphosis of a state-owned energy company from a lumbering run-of-the-mill fossil fuel incumbent named DONG (Danish Oil and Natural Gas) to a world-leading wind power innovator Ørsted.

There’s an entire chapter devoted to Bill Gates, from his international and domestic politicking to his founding of Breakthrough Energy Ventures to fund decarbonization startups.

The story of Bryony Worthington (now Baroness Worthington), the British environmental campaigner who was instrumental in getting the UK to adopt some of the world’s most ambitious climate targets even while convulsed with Brexit-related chaos.

A profile of Fatih Birol, the Turkish economist who transformed the International Energy Agency from an oil markets management club to the world’s most influential intergovernmental forum on clean energy technologies.

This book feels very much like a first draft of history: if I had to give one volume to a time traveler to explain where the global fight against climate change stood as of Q1 2024, Climate Capitalism is the one I’d pick. There’s been so much change so fast on clean energy and climate issues, any book becomes outdated fairly quickly, but Climate Capitalism will likely still be relevant for years to come due to its in-depth analysis of the key political, economic, and technological breakthroughs of the 2010s and early 2020s.

For current readers, it’s an ideal primer on Where We Stand Now. It just…it feels up to date, across the board, in a way that very few climate books do given the rapid pace of change in both clean energy technologies and Earth science research.

Often, when this writer reads a climate book or even a news article, they have to mentally append footnotes or clarifying clauses to oversimplified sentences that don’t take into account new developments. For example, “coal is the dirtiest fuel,” is a classic line, but Climate Capitalism adds the accurate clarification that burning coal emits more than burning oil or gas, but direct leaks of methane from poorly maintained natural gas infrastructure can add up to more overall emissions per unit from natural gas than from coal. The Inflation Reduction Act changed the financial picture for everything renewables-related in the U.S.; this book describes how it will impact each of the major technological domains it covers. China’s growth to become the world’s leading EV exporter and India’s investment in gigantic new solar parks went from science fiction to geopolitics-reshaping fact within a few years; Climate Capitalism not only discusses these trends but draws on exclusive interviews with some of the key associated figures.

Part of this is simply that Climate Capitalism is being published in 2024 and thus has a recency advantage (you can’t exactly blame books older than summer 2022 for not covering an Act that hadn’t been passed yet), but part of it is that author Akshat Rathi seems to be just really good at his job. He’s able to wangle interviews with Chinese executives who rarely talk to the English-language press, integrate information from across disparate technical, economic, and political fields, and convey it all to the reader in engaging, accessible prose.

One particularly endearing feature of Climate Capitalism is the presence of paragraphs that neatly explain vital concepts in non-technical language, an all-too-common omission from nonfiction literature but vital for a deeper understanding of the issues being discussed. Read Climate Capitalism, and you’ll get not only the stories of major decarbonization technologies and actions, but expertly crafted and easily digestible explainers of a wide array of related topics. These include:

How exactly a solar panel works

How lithium-ion batteries are manufactured

How cement is made and what points in the process emit greenhouse gases

How a stock index relates to shareholders’ voting rights

How a venture capital fund works

What a hostile corporate takeover needs to succeed

How governments using reverse auctions for electricity bids can help solar power development

The difference between Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 emissions

And lots more. While on the journey of learning more about how modern human civilization is trying to decarbonize, you’ll learn a lot more about how modern human civilization works in the first place. Here’s a list of some of the things I personally learned for the first time from reading Climate Capitalism.

Not a single car company anywhere in the world has ever managed to become globally competitive without substantial government support.

The incredible story of Wan Gang, the Chinese bureaucrat who personally managed to convince what was then the world’s largest country to bet heavily on then-untested battery and EV technologies.

Just to what extent solar power development has become a literal lifeline for small-scale Indian farmers. Per Climate Capitalism, “A 2017 study found that nearly 60,000 Indian farmers have killed themselves in the last thirty years because of crop failures linked to climate change.” The book profiles Srinivas, a farmer who leased his land to build the massive Pavagada Solar Park and was able to use the resulting revenue to send his daughters to university.

That Bill Gates personally met with key swing vote Joe Manchin several times to ensure passage of the Inflation Reduction Act

That the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), established to support the renewables transition, hasn’t turned out to be nearly as effective as a rejuvenated, formerly fossil fuel-focused International Energy Agency (IEA) which under Fatih Birol’s leadership played a key role in coordinating international emissions reduction targets. A major reason for this is that the IEA had strong preexisting institutional relationships with various nations’ energy departments and ministries.

The story of the Tvindkraft project: at one point the world’s largest electricity-generating wind turbine, built in 1978 by a group of Danish high school students, and eventually inspiring a nationwide industry.

How the n-type and p-type silicon layers in solar panels got their name, and how they supercharge a solar panel’s basic function of photons knocking electrons off silicon. Per the book, “N-type silicon is made by mixing silicon with a tiny amount of phosphorus or arsenic-elements that have one more electron in their outer shell [than] silicon’s four. Similarly, p-type silicon is made with minuscule loads of boron or gallium-electrons that have three electrons in their outermost shell….Because n-type has an excess of electrons and p-type has electrons missing, the layering creatures a junction with an electric field across it.” This makes it easier for photons to push the electrons off the n-type silicon, as they’re already being “pulled away” by the electron-lacking p-type layer. Classic valence electron chemistry, producing clean power with no moving parts!

Ultimately, the lesson of Climate Capitalism, drawn out from the evidence of a dozen in-depth case studies and the global exponential growth of clean energy, is a deeply heartening one. We do not, in fact, need to destroy and rebuild all of our economic and governmental institutions to deal with climate change; we just need to reform, focus, and direct the systems we already have, overcoming fossil-fueled corruption to unleash our innovation-driven clean energy future. The kludgey politico-economic mishmosh of a global civilization we have right now, with democracies and autocracies and free-market-ish companies and state-owned and state-subsidized companies and tariffs and regulations and government-funded research labs and eccentric billionaires and venture capital funds and stakeholder revolts and all the other moving pieces, is gradually turning towards clean energy, thanks to lifetimes of dedicated work by a worldwide assemblage of extraordinary people.

If you read Climate Capitalism, you’ll get a much better sense of how the world works—and how it’s starting to work better.

Thanks so much. In 2024 I’m trying NOT to read every climate crisis book on publication, so I’m a reluctant reader of something like Climate Capitalism, but after reading your review, I’m convinced it’ll be a bedrock of this year’s reading.

This one has been on my TBR pile for awhlie! Time to move it to the top.