The Weekly Anthropocene: Effective Altruism

A Deep Dive into the Wild, Weird World of Humanity and its Biosphere

In this Deep Dive, I’d like to offer a “10,000-foot view” summary of effective altruism, often known simply as “EA”, a fascinating new socioeconomic movement. If you’ve previously read about effective altruism, this post will probably seem ludicrously oversimplified. If you haven’t heard of it before, or the name just rings a faint bell, know that this is an extremely brief introduction to a complex and multi-faceted school of thought1, that may well end up being one of the most influential ethical/economic theories of the 21st century.

The Moral Imperative

Arguably the philosophical core of EA is a thought experiment proposed by famed and controversial ethicist Peter Singer in a famous 1971 essay. To paraphrase: it asks what would be the right thing to do if, when walking by a shallow pond, you saw a small child drowning in it, on the point of going down for the last time. Clearly, one is morally obligated to jump in and save them. To extend Singer’s metaphor: would that obligation change if you happened to be wearing extremely expensive clothing that would be ruined by water damage, or were about to be late to a crucial meeting where merely attending on time would earn you a large amount of money? Intuitively, no: when we have the opportunity to save a child’s life we must take it. However, as Singer points out, in the modern, globalized world, everyone has the opportunity to save a child’s life, often at a relatively low to middling financial cost.

“If it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it…It makes no moral difference whether the person I can help is a neighbor's child ten yards away from me or a Bengali whose name I shall never know, ten thousand miles away.”-Peter Singer.

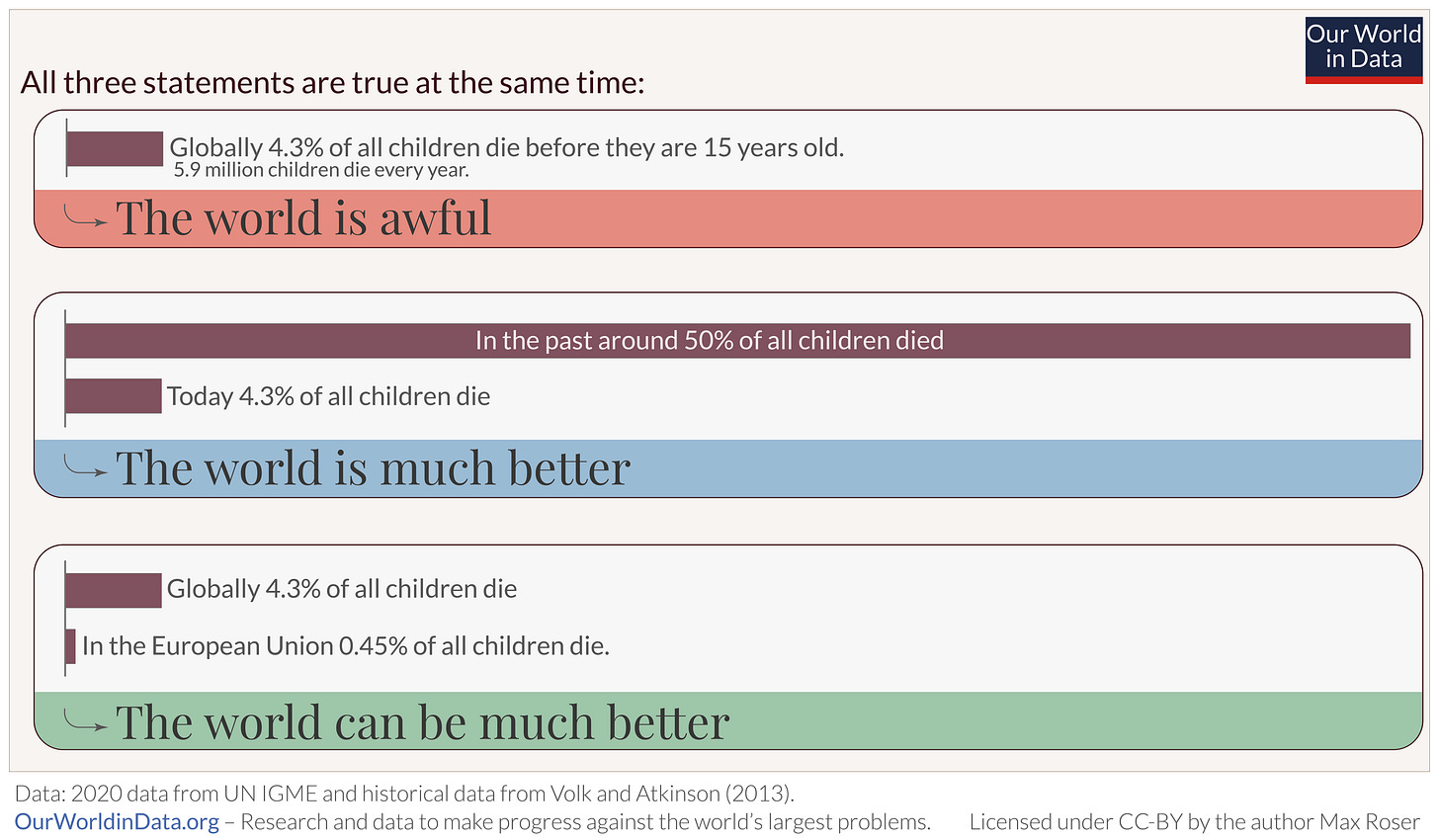

There are children drowning in metaphorical shallow ponds all over the world: 5.9 million children die every year, the vast majority of them in impoverished countries from causes that would be easily preventable in rich countries, like malaria, parasitic diseases, malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies. (Important note: before getting too depressed about this, keep in mind that due to modern medical technology we are living in the best era for children in history: about 4.5% of children worldwide die before the age of 15, compared to 50% before the Industrial Revolution. However, there’s room to do better still: only 0.45% of children die before the age of 15 in the European Union. As this excellent Our World in Data article puts it, three things are true at the same time here: The world is awful. The world is much better. The world can be much better).

And yet, most people do not give money to initiatives working to reduce these avoidable deaths, even when they could easily afford it. That’s the “altruism” part of effective altruism: we should extend our natural altruistic impulse to save children, and donate to save the lives of children in faraway impoverished countries.

The Real-World Calculation

But wait a minute: it’s not so clear-cut as all that. The thought experiment is set up for moral clarity, while the real world very much is not. When you see a drowning child in a shallow pond, you know that you can save them, but it’s far from clear that a donation to “help dying children in developing countries” will actually save a life. Aid money to poor countries’ governments is very often embezzled by dictators. Many so-called charities have highly inefficient financial management, with some being little more than scams that spend less than 4 cents on the dollar on actual charity work. (Here’s a list of the 50 worst). Furthermore, poorly thought out charitable programs can sometimes cause more problems than they solve: to take one of many examples, the West donates lots of complicated medical equipment to African hospitals in an effort to save lives, but it almost always breaks very quickly and then can’t be repaired with local technology, leading to useless “equipment graveyards.”

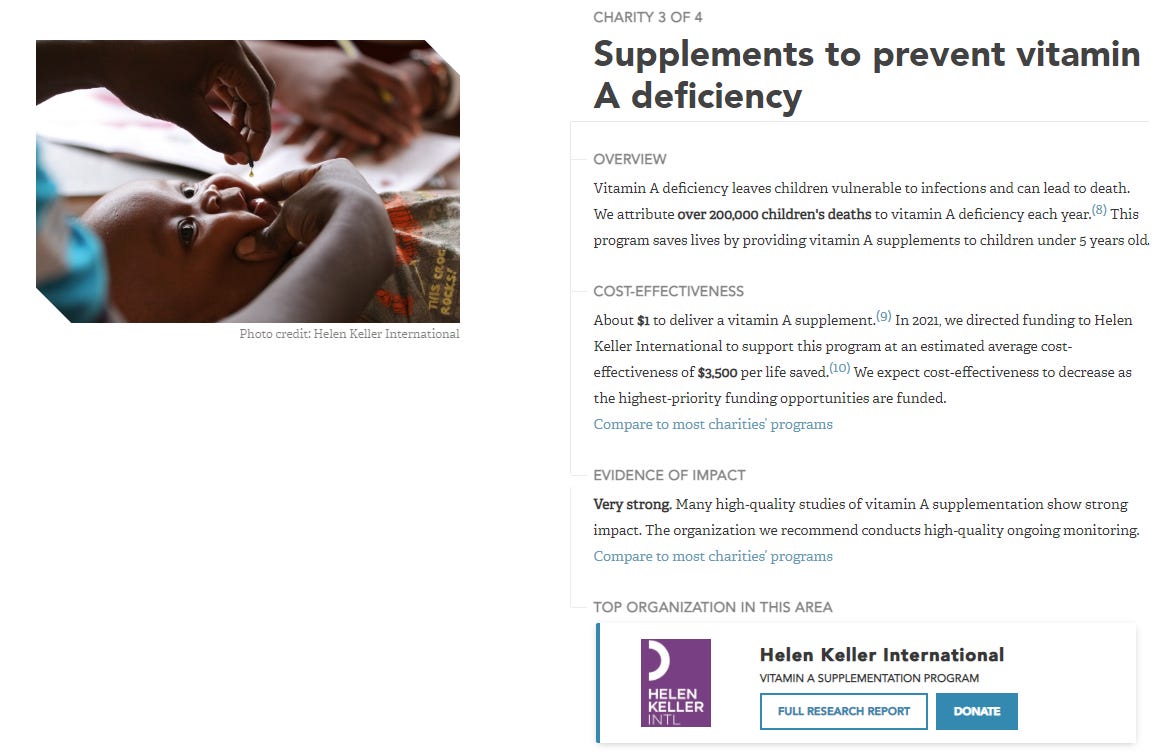

That’s where the “effective” part of effective altruism comes in. Early effective altruism organizations, like Giving What We Can and in particular the unparalleled GiveWell, try to function as “meta-charities”: putting a vast amount of ongoing time and effort into researching the best charities. (Here’s a great article on GiveWell from The Atlantic). And they’re strict, conducting exhaustive research programs that investigate the charity’s finances, the long-term outcomes of their interventions, the marginal value of a donor’s dollar, and any potential negative unintended consequences. Full research reports for their top-ranked charities, along with a bunch more transparency-focused information like a list of all the times they’ve made mistakes, are available on their website. At the moment, GiveWell ranks only four charities in the world as highly effective Top Charities: the Malaria Consortium, the Against Malaria Foundation, the Helen Keller Foundation’s vitamin supplements program, and New Incentives’ vaccination program, all of them working on preventable health issues in sub-Saharan Africa. All four have been evaluated to save one child's life, on average, for every $5,000 donated. (Pictured, below: screenshots from the Top Charities page).

The Climate Connection

Effective altruism may seem fairly off topic for a newsletter primarily concerned with the relationship between humanity and its biosphere, particularly when it comes to climate change. But it’s really not. The kind of people being helped by GiveWell’s top charities-desperately poor children in sub-Saharan Africa-are also the people most imperiled by the climate crisis (here are some details). They’re also the people who’ve done the least to contribute to that crisis, and are receiving very few of the benefits of the global technological civilization producing all these carbon emissions. Donating in an “effective altruist” style, specifically to save the lives of African kids through programs that have been rigorously evaluated to be efficient and effective, is a way to share the medical riches of modernity with the people who are most at risk from the climate damage it has caused.

The Call to Action

Normally, this writer is fairly uncomfortable sharing personal details, especially involving money, but a new paper found that talking about one’s donations is one of the best ways to encourage others to donate, so here goes. Since having started a new job in September, I’ve instituted a new effective altruism-based habit: on the first of every month (started October 1st) I’m now donating 2.5% of my after-tax income earned from that job during the previous month to a GiveWell top charity. This percentage is of course very small, and I hope to increase it gradually over the next few years as my personal finances improve. But the point is to build a habit, and continue giving to effective charities for a long time at a sustainable pace. If you can afford it (don’t harm your own well-being!), I invite you to consider taking a similar step.

I’m focusing on this article on traditional “core” effective altruism. There’s also a more controversial wing of effective altruism, also known as “longtermism,” that tries to extend the morality logic to hypothetical people living in the future, which leads to calculations that the most important places to donate would be organizations trying to reduce “existential risk", like nuclear war, that could drive humanity extinct and prevent the lives of trillions of future people. There’s also a much more controversial sub-splinter group of longtermism which believes that the creation of a super-intelligent AI is imminent, and that in turn could either solve all problems or drive humanity extinct, and so the single most important thing to do is fund cutting-edge research into how to get an AI to align with human values. (Seriously). This is all fascinating philosophically (and is a long Internet rabbit hole to go down, if you’re interested) but a lot less evidence-based and morally clear than the simple reality that a relatively small amount of money could save the lives of kids in Africa.