The Weekly Anthropocene, December 13 2023

Black rhinos arrive in Chad, white hydrogen found in France, deforestation drops in Brazil, a climate survival plan in the Marshall Islands, indigenous land back in Ecuador, and more!

Holiday schedule: this is the last weekly news roundup of 2023. We’ll be publishing extra content for the remainder of the year. We’ll restart weekly news roundups (with exclusive paid subscriber content as well!) in January 2024!

There are so many more amazing stories I want to write about—please consider a paid subscription to The Weekly Anthropocene!

Chad

Renowned conservation NGO African Parks has pulled off another successful long-distance translocation: flying five black rhinos from South Africa to Zakouma National Park, Chad, an epic 4,400-kilometer journey. They will join the two black rhinos currently living in Zakouma (both female), and hopefully establish a viable breeding population of black rhinos in Chad for the first time in decades!

This is just one of the many fascinating rewilding projects African Parks is leading across the 22 protected areas in 12 countries that they manage. Now that they’ve acquired 2,000 southern white rhinos from a defunct ranch in 2023, African Parks will be conducting many more rhino translocations to national parks in the upcoming years!

France

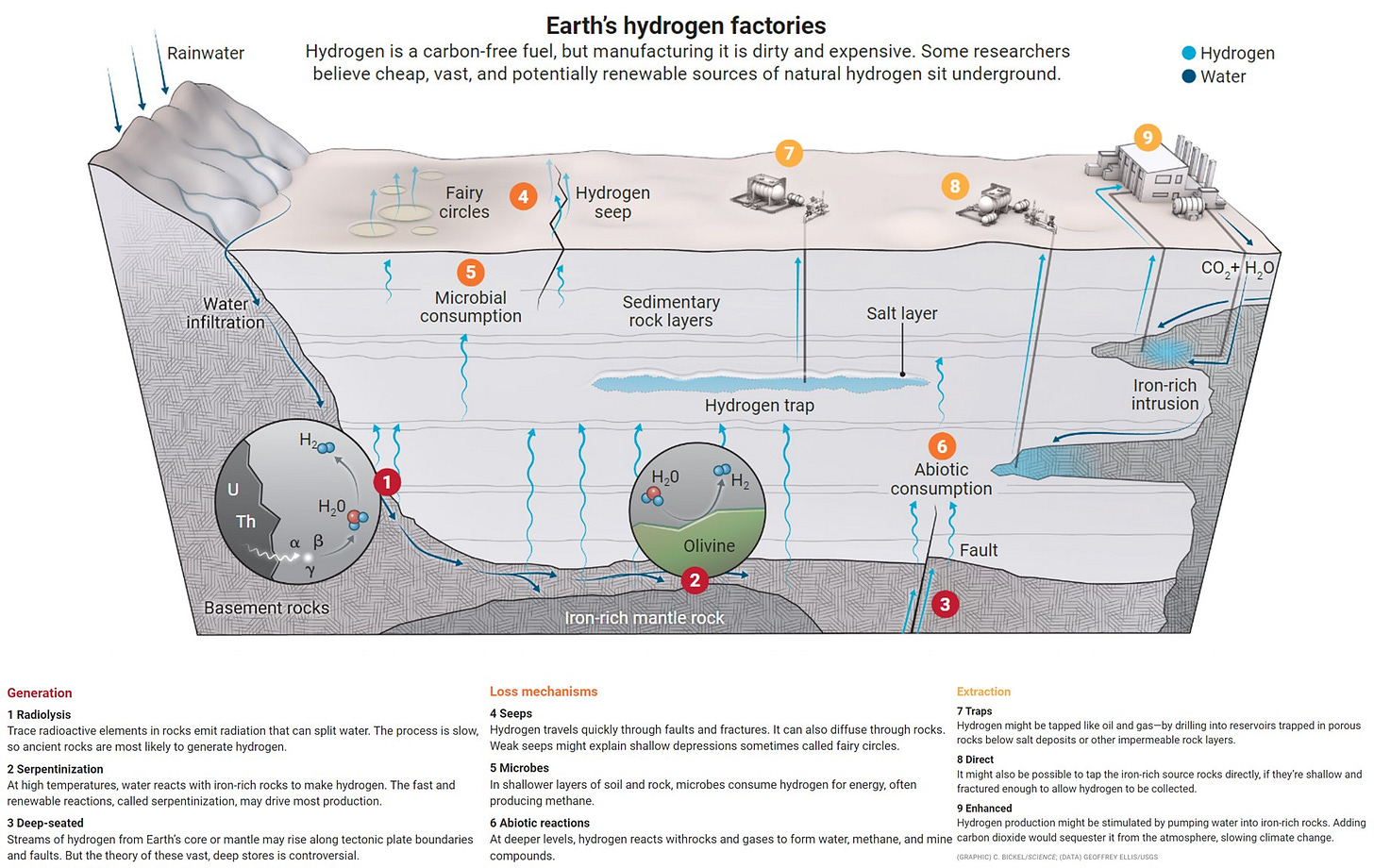

You may have heard rumblings over the years about a “hydrogen economy” of technologies powered by burning hydrogen. (Hydrogen also has many preexisting non-fuel uses, like producing ammonia for fertilizer). There’s a whole “rainbow” of terms for hydrogen originating from different sources, like “green hydrogen” for hydrogen made by renewable energy-powered electrolyzers, “pink hydrogen” made with nuclear power, “gray hydrogen” made with natural gas, “black hydrogen” made with coal, and “blue hydrogen” for a complex boondoggle that’s politically useful in getting fossil fuel companies to support the IRA, but unlikely to be seriously technologically or economically relevant. There was a brief wave of excitement a while ago over hydrogen fuel cell-powered cars, although it turns out that battery-powered EVs work much better. Ultimately, none of the green hydrogen hopes have come to all that much: moving electrons in batteries and power lines is just intrinsically much more efficient than using electrons to produce hydrogen and then move the hydrogen to be burned somewhere else. So far, hydrogen has been mostly a confusing sideshow in renewables technology compared to the exponential global growth of solar and batteries.

But that might just be able to change, with the discovery of a massive deposit of white hydrogen in France by scientists at the University of Lorraine. White hydrogen is a relatively new discovery: unlike green, pink, gray, black, and blue hydrogen1, it’s not created by industrial processes but naturally occurring in pockets buried in Earth’s crust. You can drill for it and burn it like oil: the world’s first “white hydrogen well” was a small project in Mali in 2014. The Lorraine deposit may have up to 46 million tonnes of white hydrogen (over half of the world’s current annual production of gray hydrogen, 80 million tonnes) and there appear to be other white hydrogen deposits in the Alps and the Pyrenees in France alone, with untold others around the world. In Lorraine, new sample drilling going 1.8 miles deep should start in 2024, with hopes for commercial extraction of white hydrogen by 2027 or 2028.

White hydrogen is particularly interesting as a source of clean energy that really, really closely resembles our historic fossil fuel industry, and thus doesn’t require major new technological breakthroughs to use; it’s a gas found underground that you drill for, then burn to produce heat or turn turbines to generate electricity. It’s just that when you burn hydrogen, you get water (H2O, H plus O molecules) instead of carbon dioxide (CO2, C plus O molecules). Between enhanced geothermal and white hydrogen, a good Anthropocene might turn out to include a surprising amount of drilling—but for emissions-free energy sources, not fossil fuels!

California

In 2020, a severe wildfire struck California’s Big Basin Redwoods State Park, severely charring the coastal redwood forest. Now, a new study has found that the redwood trees used decades’ worth of stored energy reserves to help regrow, with sprouts emerging from buds that had lain dormant under the bark for as much as 1,000 years, As one researcher told Science magazine, “This is one of those papers that challenges our previous knowledge on tree growth.” Fascinating news!

In October 2023, this newsletter wrote about an awesome new initiative vaccinating captive California condors against the scourge of bird flu. Now, on November 28, 2023, six young captive-born California condors that had been vaccinated against bird flu were released into the wild in San Simeon, California. (Interestingly, one of them, Condor 1139, was released then flew back into the pen to stay behind with another condor; both flew out together the next day).

Epic progress for an awesome confluence of two of humanity’s most noble endeavors: wildlife conservation and vaccines! Excellent work.

Brazil

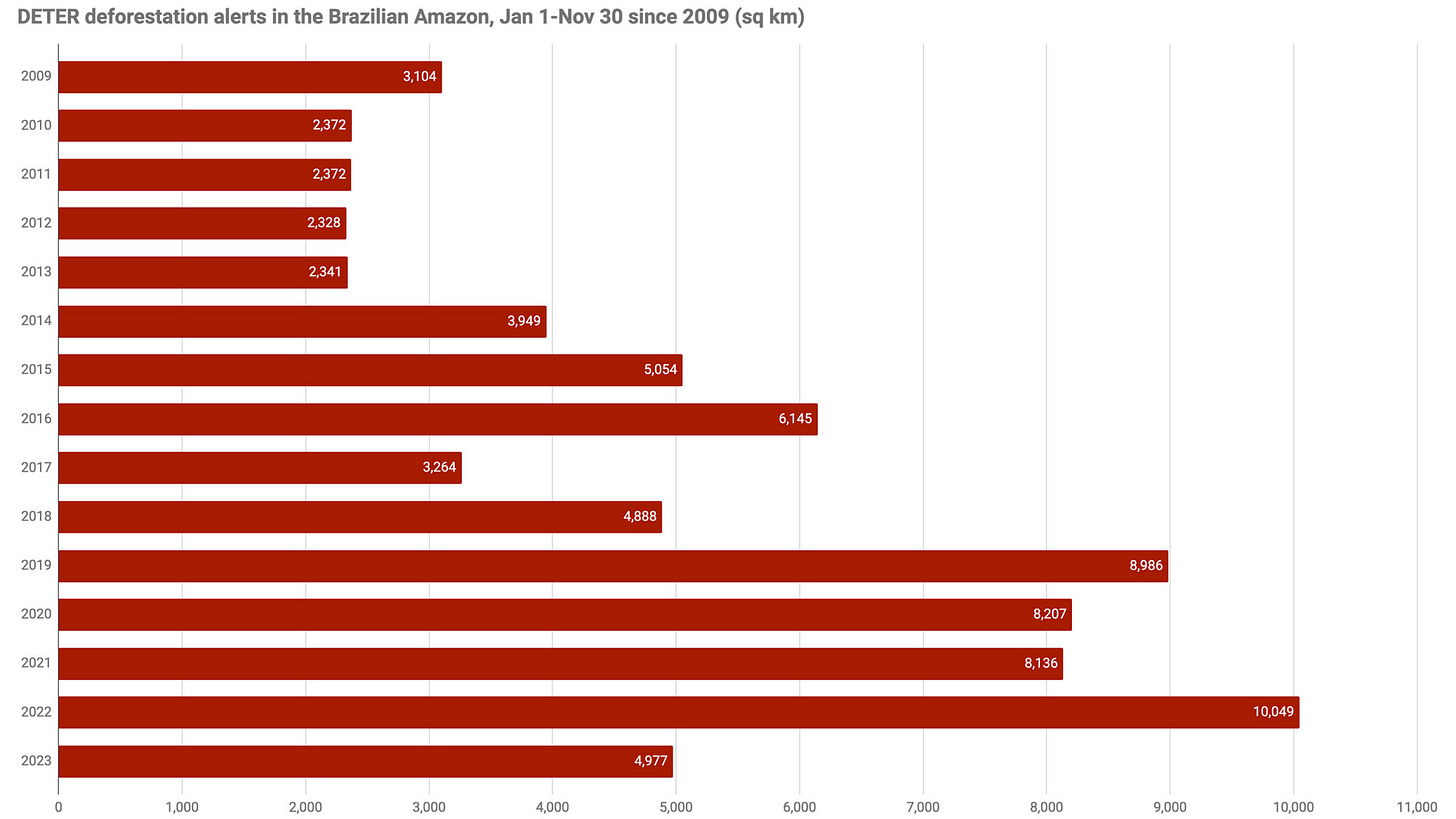

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has decreased for the eighth month in a row, despite the extra difficulties posed by an ongoing severe drought. In January through November 2023, 4,977 square kilometers were deforested, a 50% decrease from the 10,049 km2 lost in January-November 2022 under Bolsonaro. Progress continues!

Marshall Islands

The Republic of the Marshall Islands has published one of the most detailed climate survival plans in history at COP28. Composed of dozens of low-lying coral atolls with a land mass collectively smaller than Baltimore, the Marshall Islands are extremely vulnerable to sea level rise, and they estimate that it would cost $35 billion, or $800,000 for each of the 42,000 residents, to build enough sea defenses and desalination plants to ensure the nation remains habitable. Given that saving a child’s life from preventable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa currently costs about $5,000 as of 2022, it’s sadly difficult to see such a project as a top global funding priority even from a purely altruistic perspective.

The Marshallese plan is clear-eyed about the hard choices the nation will likely face at “decision points” in 2050, 2070, and 2100, with potential options including consolidating population from 24 to 4 atolls around 2070 to make it easier to protect everyone and, if sea level rise continues, evacuating the entire population around 2100. Although the Marshallese people reportedly very much hope to be able to stay on their islands if at all possible, they do fortunately have a “worst case scenario” backup option of moving to America, as the Marshall Islands have a Compact of Free Association with the USA that grants freedom of movement rights. Springdale, Arkansas, or “Springdale atoll,” is already home to a thriving community2 of 12,000 Marshallese migrants. The Marshallese people have been dealt a very bad hand in the Anthropocene, but they’re doing their best to face the future with grace and determination.

Ecuador

In November 2023 in Ecuador, a court granted the Siekopai indigenous nation ownership over 42,360 hectares of their traditional Pë'këya territory, a patch of Amazon rainforest on the Peruvian border that includes many of the culture’s historic and sacred sites. (42,360 hectares is 423.6 km2 , or larger than Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx combined). During the case, a Jesuit document dating from 1753 was instrumental in proving that the Siekopai were the historic inhabitants of Pë'këya. This is a welcome new chapter in the broader story of widespread reclaiming of indigenous lands in recent years; lands owned by indigenous and Afro-descendant communities grew from 16.7% of Latin America’s land area in 2015 to 17.6% in 2020, with more progress since!

To be clear, all actual physical hydrogen is colorless, the colors are a mnemonic system to keep track of origin that everyone seems to have agreed on using for some reason.

Quote from a Ph.D. thesis about Marshallese culture in Arkansas that I couldn’t resist sharing: “For example, in a tent on the side lawn of the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History in downtown Springdale, efforts are underway to build a traditional-style Marshallese mid-sized outrigger canoe, or kōrkōr. Although Arkansas is a landlocked state, it is not without bodies of water such as Beaver Lake, a large reservoir near Springdale. Miller (2010) shows that the canoe is an important part of Marshallese culture and identity. Traditionally, it would be carved from the trunk of a breadfruit tree. However, as it would have been quite impractical to get such a large, heavy material from the Tropics to Springdale, the Arkansas kōrkōr is being made from the trunk of a native sycamore.” A traditional Marshallese canoe in Arkansas! And some quick Googling found that it did get built! So cool.