Andy Revkin has been a longstanding climate reporter for The New York Times, member of the Anthropocene Working Group, a director at the Columbia University Earth Institute, and a songwriter and accompanist of Pete Seeger. He now writes on Substack as

at .As background for this conservation, Andy particularly recommends the

pieces “How to Defeat the Climate Change Complexity Monster” and “With Billions of Dollars to Invest in Clean Energy and Resilience, Here's the New Climate Communication Challenge.”Bold text is The Weekly Anthropocene, regular text is Andy Revkin.

Well, Andy, thank you so much for joining us. I really appreciate it. I really appreciated our talk on the Sustain What? platform and your webcast. That was amazing. And I'm really looking forward to talking with you again.

My first question, really, the thing that I'd most like your advice on, is a sort of perception I've had that the script has kind of flipped on the climate movement from what it was when I was a kid. And obviously you have more experience with this than I do. My nascent gestalt feeling of how things have changed from, say, 2010, is that there was once a three-point sort of belief on how climate change needed to be solved.

Point one was that a public broad-based social movement akin to the civil rights movement was needed, in order to

Point two, convince governments and corporations who wouldn't take action on their own, to

Point three, make sacrifices to install renewables technology because renewables tech hadn't become economically competitive yet.

And the belief was that we have to limit energy use or generally make hard tradeoffs to address climate change. And I would just like to advance the proposition and bounce it off you and see how you think, that none of those three really appear to be true. And yet we're making great progress on climate change, in part because some of those aren’t true.

We haven't gotten really that much of a public social movement. We've gotten some great people who are really clued in and doing great stuff, like 350.org. But I don't think you can argue it's really a dominating publicly rooted movement today.

Because in many ways, I feel like we've seen a flip where the belief was that we need civic activism to pressure government to get corporations to change. And like now, I feel like we switched into this place where governments and corporations want to change, despite, in some cases, popular opposition. A lot of the big climate change related social movements have been anti-climate action, like the gilet jaunes in France. A carbon tax couldn't even pass a referendum in Washington state.

So I'm kind of shocked by this, because like when you see these things like Republican states’ elected officials trying to pass rules to lock in the fossil fuel industry like in West Virginia and like Texas and others’ Attorney Generals going after ESG and going after corporations trying to do their own investments with renewable energy, I'm like, wow, this is topsy turvy.

Like, this seems like the reverse of what I thought I'd be part of as a kid. In a good way, because major actors like companies and governments have changed faster. But we've got this far right, what Robinson Meyer calls “carbonism,” just sort of an ideological attachment to fossil fuels. That's formed, I would argue, at least as powerful, sadly, a social movement as the public push for action on climate change. Like, I really didn't expect to see a state government trying to stop BlackRock and major utilities from moving further on climate action, you know? I expected state governments needing to push corporations to move faster on climate action.

But now, I don't know if you've heard the term “greenhushing,” we're seeing that a lot of companies are wanting to do moving to renewables and climate action because it's economically profitable and are wanting to not publicize it because in some places it makes you part of a culture war. And that's just kind of shocking to me. I think they're doing that because point three is not true, you don't need to make sacrifices to install renewable technology. Solar is the cheapest electricity in history. I think this is happening because you don't actually need to care about the planet to be willing to make big changes on climate change.

So that's my perception of what I'm seeing and I'd love to know what you think.

Boy, there's a lot there. I mean, I have my own sense of a learning curve on what the climate problem was. I really like Bill McKibben. He and I have been on this journey around climate change since the 80s. My first big article on this was 1988 and then his book came out in 1989.

And he chose an activism path and he and I have sort of sparred over the years because as a journalist whose activism is my journalism, my activism is around reality. Like I'm an activist for what's real. And so I'm not a campaigner, but I've studied the campaigns. And now that I'm an opinion journalist, which is really what I am now, I still have my own ideas, but I'm just passionately addicted to reality, even when it's uncomfortable, even when it's gray. So looking back at the climate movement part, I think, as you say, their theory of change is press enough, build a community, and you don't need a majority. There's some past progressive theory of change that if you get a certain percentage of people, I can't remember what the number is.

3.5%?

Something like that. That can become a lever for bigger change. And that has worked on other issues. Gay marriage is a good one to look at. And it wasn't just activism. It was some Republicans realizing that their children are gay and that they should be allowed to be gay. So social change like that can be propelled through activism, civil rights, as an example, of course.

But energy realities are what butt up against that. You know, 2008 was the Great Recession and a lot of people in this country were in what's called energy poverty, you know, and Obama recognized this. He did a White House South by South Lawn thing, you know about South by Southwest, the Texas hipster, you know, kind of thing.

They did a South by South Lawn event where Obama is sitting there on the green with Katharine Hayhoe, the scientist, and with Leo DiCaprio, the movie star activist. And they were talking about, you know, the need to drive change. And Obama said, well, yeah, yeah, but you have to remember the guy who's got to drive 40 miles to his job in Ohio.

Yeah.

His activism is about being able to maintain his job and get home and still afford to put food on the table and stuff like that.

And Obama was saying this, he kind of recognized the nuance. And so that activism model doesn't really work for something that's as systemic and deeply embedded as our energy norms. As I've said before, it took a hundred years to invent suburbia. And you just don't uninvent suburbia overnight, it’s just one facet of transportation, the need, the fact that we're a spread out country.

And you can't like, have have marches in the street and think you're going to wake up one day and have everyone have a heat pump. It took us, you know, we spent $10,000 in the house we moved into here in Maine a couple of years ago to put in a heat pump and another one in the garage apartment. And they're really good and they're surely cutting our energy needs. But my neighbors don't have the money to do that, even with what's coming through the Inflation Reduction Act. Maine has been ahead of the game on that because of their state incentives, which is what we took, which is what we used.

And so I think the activism model is mainly, the theory of change is about Congress and pressure on presidents. In 2011, there was a lot of pressure on Obama about Keystone Pipeline. It’s like the LNG fight right now, the fight by Bill McKibben and others to stop, to pressure Biden to constrain expanding LNG exports.

Here we are, you know, in the run up to a very consequential election, the same thing happened with Obama in 2011 and run up to his reelection. And in that case, Obama punted, he said he was going to put it off the decision. And he ended up in his second term saying no to Keystone.

But, that's the model of change. You know, we get into the streets, we blockade, I think they're planning to go to the Department of Energy and have a sit in, and it's all fine and good.

But you know, as a journalist, my job is essentially to be caustically honest. My job isn't to have a lot of followers or, you know, be in a sort of Pied Piper mode. I'm a Pied Piper for people who are interested in reality, even if they're pursuing a campaign. It's good to know what the baseline is. So that's like your first point.

Your second point about government is, I think now, as you said, we are in a different moment. A big chunk of the activism in 2009, 2008, 2010 was about getting a climate bill.

Yeah, and we got one!

Yeah, but back then it was a different kind of climate bill. It was regulatory. It wasn't a stimulus.

Yeah, we didn't get Waxman-Markey. We didn't get Cap-and-Trade, but we got sort of the supply side climate bill. We got the carrot and not the sticks.

Yeah, and by the way, that says a lot because sticks are just very hard to apply, where you have a country with a mixture of energy needs and where sometimes that activism can propel counter activism. The Republicans have gone a long way in trying to cast this as an elitist movement and “they're trying to raise your cost of energy” and that kind of thing, even without the regulation.

So now the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which is like a trillion dollars, and a significant chunk of that is, you know, the grid and cleaner energy. And then you have the Inflation Reduction Act. We're now in a moment of resource abundance.

And the activism that's needed, to my mind, is exactly what Jigar Shah of the Biden Administration said on my webcast a year, maybe it was a year and a half ago. He said, look, we have these resources now, but we can't force you to take them. We need someone in every town in America to go to the school district or to go to the town council meeting or the city council and say, hey, you know, half of our streetlights are still incandescent and here's a loan we can get that pays off in eight months and then becomes a way for us to save scads of money.

So he's turned it around. The activism that's needed is local. It's about people getting involved in their community change making process. And it's not about this high level pressure on government to solve the problem for us by putting a carbon tax in place, that kind of thing. So I think this model of abundance and opportunity is it.

Yeah, and I really strongly agree. And this is something I've tried to say. I said it in a couple of recent interviews. And to his great credit, Bill McKibben has called for climate activists to embrace abundance. I'm sure you saw that great Mother Jones article, Progressives must learn to love the green building boom.

But I do think that in sort of a more logical world, where people were able to step back and look at the broader context, and we're not so driven by the incentives of organizations that already existed, the thing that would have made sense, in my opinion, for the American climate movement would be to say, “Okay, we have won the biggest climate bill we are likely to ever realistically get. And those are uncapped tax credits so it could potentially be as big as we make it.” So this is what I would have said if I was in the room at 350.org in like September 2022: “We should switch our entire focus from lobbying politicians to engaging citizens and the business community to take advantage of the stuff that we just got the politicians to do, that we just won.” And the fact they didn't do that honestly really disappointed me because it sort of seemed to say that activist organizations by their nature will try to self perpetuate as activist organizations even if that's not what the time calls for. Like if you're trained to campaign, if your job is campaigning, if your professional experience is campaigning for federal action, it's hard to switch away from that once you have it.

You mentioned the protest in front of the Department of Energy in 2010, 2011 against Keystone XL. I'm on Bill McKibben's email list, great guy, interviewed him last summer. He's planning, with ample justification, almost an identical play, going to the Department of Energy in February to potentially get arrested to stop the liquefied natural gas terminal buildup. And those LNG terminals are bad projects!

But I mean, honestly, I don't think it's a good idea, especially with, as you said, an incredibly consequential election on the line, for there to be daylight between the Biden administration and the climate movement right now.

Like, my proposal, sort of a radical proposal, is that basically the climate movement should stay on message. And the message should be, “the Inflation Reduction Act is great, vote to reelect Biden.” Like, start talking about stuff that Biden can do better in 2025! In my opinion. Once he gets reelected, follow that Keystone XL model, Obama punted on that, got reelected and then closed it down in the second term.

[Since this conversation, it looks like the Biden Administration has listened to the climate movement and taken steps towards halting the LNG export terminal expansion, without a noticeably strong political backlash so far].

I don't know, maybe it's social media driven. I don't know what it is. There's sort of an attempt to attack Biden from the left on climate. And I feel like that is massively misguided because Biden has just delivered the biggest climate wins in American history. And we need to lock those in and get reelected before we start pushing for more.

So I've tried to write, hey, you know, the Willow Project, it's a bad project, but Biden actually needed to approve that to appease Murkowski and Manchin, and it might not even be economically competitive by the time it's done. So its climate impact might not be that huge. I've kind of tried to say, you know, Biden's actually doing overall really great work on climate. And I feel like that message has just gotten lost. And I feel like I'm really disappointed in the climate groups that they haven't rallied more strongly behind Biden in the wake of the Inflation Reduction Act. Let me know what you think of that.

Oh, yeah. Well, you know, I guess it gets back to this theory of change business. This fight came up again back in the days of Keystone. Bill was chaining himself to fences in Washington and getting arrested. I let him do a guest post on my blog at the time, dot earth at the New York Times, where he was kind of saying, look, if you're not here or down here chaining yourself to the White House, you're not serious about this issue.

Activism is a mission, it has to have opponents and it's very much built around a model where there are bad guys and good guys and we're the good guys and come on, let's all get together and do our thing.

But we have to have deployment of infrastructure on the scale that's needed for this energy transition. And so whether it's permitting reform, whether it was Keystone, whether it's LNG exports, if you're an activist, it's all about your lens on the world.

You mentioned carbonists. There are definitely carbonists out there, but the “climatism” problem is if you're putting climate, the climate emergency, climate change as your foreground monumental focus, then that means it's really hard to have a useful conversation with, for example, folks in Iowa, a Republican state that's put up an amazing amount of wind and cut its coal use. So Iowa’s like a climate leader, they just don't call it that. They're not doing it for climate reasons.

That's how we win! That was my point. We get people who are not at all invested in the environmental case for solving climate change, doing the most important action needed to solve climate change, because it makes them money! I think that's great.

And then as far as Biden goes, this gets to this issue of, there are very few single issue voters who will go to the ballot box in November based on climate. There'll be maybe a couple million across the country. But then if you're not paying attention to Biden's international security policy, the fact that we do have allies and developing countries for whom restricted supplies of LNG going into the global commodity market will raise the price of the fuel. Bill has posted on Twitter recently some counter arguments there related to the carbon cost of shipping and liquefying the gas and stuff. But that, because there's a lot of murkiness in those data, that's a cover for basically an ideological attachment to the grand transformation away from fossil fuels, period. And when you do that, you negate issues that are real-time crisis issues.

Yeah, like energy poverty, like you said. There’s an emerging North-South divide and for Africa in the longer term, China and India very short term, people are like, okay, you got rich off fossil fuels, and now you want to stop us from doing the same.

And I think that the sort of approach the Biden and Democratic Party settled on of carrots instead of sticks is really good because American carrots can help the world, but American sticks can't.

Like, if somehow we got incredible political consensus to absolutely phase out the use of fossil fuels in America by 2030 with some insane Herculean effort, that would not change the calculus in India and China, except indirectly through politics. However, the Inflation Reduction Act means a whole bunch of new technologies and businesses will be developed in America, with subsidies for like carbon capture and advanced nuclear and geothermal and a bunch of other stuff. And those technologies, once they exist, will benefit the entire world.

I think that the activism driven, state driven, regulatory driven model of “identify and punish the bad guys” works great when it's social stuff that does not require massive physical infrastructure transformations to fix, because then you can actually kind of name and shame bad guys. And that actually fixes the problem if it's a discrimination issue or something like that.

But for fixing climate change, we actually do need massive sort of infrastructure shifts and technological shifts. We needed the huge developments in solar panel manufacturing and battery chemistry we've had in the last couple of years. One lens I'm trying to put on it is we really, really have shifted from a sacrifice mindset to an abundance mindset, at least in the real world and in adapting to climate change. And I feel like that hasn't quite been reflected in the climate movement yet. I'm not sure what your take on that is.

Well, again, it depends on who you define as the climate movement. The movement that's most visible on social media and the like is clearly the Bill McKibben, Emily Atkin, Fridays for Future, Extinction Rebellion cadre. And they will not, I don't think they're going to change.

And I do think in a way, it's like the wild rumpus in that children's book by Maurice Sendak, Where the Wild Things Are, you know, let the wild rumpus begin.

Democracy and complexity of human reactions to problems requires a range of responses.

And I started writing way back actually during the Keystone thing, I was so frustrated with the idea that you can't have a macro argument along with the basic political activism argument. I started to Google around thinking, like, can, what's, can there be response diversity in environmental campaigns? What's the history of thinking about, you know, a diversity of responses to environmental stress?

And lo and behold, I found this paper from like 2003 by a Stockholm professor, Thomas Elmqvist and others, studying ecosystem resilience, the diversity of responses from species with a particular function in an ecosystem when they face an environmental stress. Like acid rain, you put it in a stream. If the plankton all react the same way to the stress, it's a brittle ecosystem. If the plankton have a diversity of responses, it's a resilient ecosystem. And I kept thinking about that in the context of social change and social stresses. And I wrote about that a little bit. And the same batch of researchers just this past year wrote a new paper on response diversity as a sustainability strategy.

And there's an increasing body of thinking around the importance of embracing a range. In other words, embracing the reality that there's eco-modernists and techno-optimists, there's Bill Gates and Greta Thunberg. Can you imagine the world ahead if we were all Greta Thunberg or if we were all Al Gore or we were all Bill Gates? It would be very brittle and we would be bound to have regrets.

You need the diversity. Absolutely. Like, I disagree with all of those people on some things. I think Greta Thunberg is kind of too apocalyptic in her rhetoric and can discourage people, and I think Bill Gates overrates nuclear’s importance, his nuclear startup TerraPower isn’t doing well.

I feel like if you time travel back to the 1980s, you could see someone saying, wow, look at the 2020s as they are now, we've already lost on climate change, there’s huge coal bleaching events extreme heat and we're about to cross 1.5 C and we're not even done with using fossil fuels yet.

And I could see another perspective where they're like, oh my God, solar is the cheapest electricity in history. Most new electricity generating facilities being built in America and Europe and China are renewable. It'll take a couple of decades, but looks like we're on the right path. We might hit like 2.5 C, but probably not 5 degrees C.

I feel like you can either tumble into despair or be incredibly energized by hope while looking at the same situation in the world right now with respect to climate change. I've tried to write more on the hope side, because I saw so many people pushing the despair side and very few people talking about the hope side. I wanted to provide a more balanced picture of reality.

Because I feel like we're kind of doing better than most people think on climate change, given how fast renewables have grown, especially. And a lot better than people expected we'd be doing as of like 2010, when it looked like we'd just keep building coal plants forever. But you know, I also grew up kind of expecting the apocalypse due to climate change. So I think we're doing better than we expected, because I expected civilizational collapse. I grew up as a kid with the IPCC’s RCP 8.5 scenario warnings that looked really, really possible.

There’s several layers here. One, over the decades, I've talked to a number of folks who are looking at long-term trends on carbon and energy and development.

People like Jesse Ausubel and Nebojsa Nakicenovic, who is one of the earliest IPCC authors, they look at decarbonization.

If you look at it with a very long lens, like from the 1800s forward, we're on a very long journey that's been happening through time as we use fuels more efficiently, as we replace old ones with newer ones.

And the thing that's noteworthy about these graphs is, you don't see much evidence of policy changes changing that long path. You see little blips when China was really in surge mode with coal in the 90s into like 2000. And I think by the way, that's what generated those RCP 8.5 kind of trajectories. There was an upward, even that decarbonization pathway, the long multi-century one shows a little blip. And so that takes me away from thinking that there's a lot you can do to change that.

I think basically the more we can spread the capacity to integrate clean energy into developing country energy development, the better, which is partially just making developing countries less poor.

Like, I'm really interested, and I'd like to maybe do a show soon on, there's a newish version of what used to be called debt for nature swaps, where rich countries that had loaned money for development to poor countries would forgive some of their loans for the sake of forest conservation. And now there's a little bit of discussion of debt for climate swaps. In other words, what can we do to just alleviate this huge debt that we've imposed on poor countries as a path to them becoming rich.

Yeah, a lot of the real progress looks like, you know, John Goodenough coming up with better lithium battery chemistry in a lab in the 80s and stuff like that. A lot of the really big inflection points are, like, complex financial instruments or esoteric lab breakthroughs or stuff that doesn't lend itself perfectly to a social movement.

Yeah. And, you know, this gets back to, one of the other longstanding debates has been the role of innovation and basic R&D, basic research and development, in driving change versus regulation.

And I had these epic debates online with Joe Romm, who was at the Center for American Progress and really punished me when I was a journalist, actively trying to denigrate me. You know, journalists always make mistakes, but activists never make mistakes. So it's easy to pick up on a journalist's mistakes and say, oh, you really got this wrong.

But we were, you know, I really was, dug in on the history of disinvestment, disinvestment in basic R&D. And not just in the United States, but all the OECD countries. From the early 70s, because of the energy crisis, there was a real burst of investment in basic R&D on energy, solar and nuclear and other things. And then it all went to sleep. And I called it like a long bipartisan slumber party on the need to support energy innovation and energy science. And I would say the same thing about agriculture, agricultural research. Especially when you compare it to things that we did spend a lot of money on for research, like defense and medicine.

The more progressive wing of the climate arena say, no, no, no, you just need scale, so that's why we need a climate bill that will force companies to move away from coal and gas and scale on renewables. When you do scale, you drive efficiency and innovation.

And that's what we've seen, it's a big chunk of what we've seen, of course, scaling got a manufacturer of photovoltaics in China to supply Germany during its early transition. That's great, but you still need basic breakthroughs too.

And if you really look back the chain at how this all happens,

Like LEDs, there was a Nobel Prize finally awarded for LED technology. And, you know, it was given to like two or three scientists, but it wasn't just two or three scientists. As you say, with lithium batteries, it was like a long, long process that led to that breakthrough to have LEDs become a truly usable form of light. And now you've got Jigar Shah saying, we have loans to give you to transition your incandescent bulbs to LED streetlights. Half of America still hasn't done that. But where did that come from? It came from a lot of hard work in laboratories and then in, you know, demonstration projects to get things bigger.

Yeah, absolutely.

And I think it's a really good point, that you brought up that the scaling and also R&D investment.

I feel like, and Robinson Meyer also wrote something similar to this, but I feel like the original sort of climate image was that it would be solved by international cooperation, with the conferences of the parties at the UN and stuff. But I feel like international competition and Cold War II between the U.S. and China might have done more to help the renewables revolution than cooperation has.

Because I'm not sure the Inflation Reduction Act would have been passed if the U.S. was in a more peaceful sort of relationship with China.

Like you said, government R&D spending for fundamental breakthroughs in energy and other technologies is absolutely critical. And historically, one of the major things that drives that is geopolitical competition.

So I'm kind of really, really hoping, like crossing my fingers hoping, that we get a perfect sweet spot where we get kind of a Green Race between the U.S. and China. Like has already really started with the Inflation Reduction Act. Like we got between the U.S. and Soviets for the Space Race. And that that stays right in the sweet spot, where it stimulates research spending, but doesn't actually end up in a war. So that's what I'm hoping for. I don't know what you think about that. But I think that competition and scary geopolitical maneuvering might actually be one of the key drivers of fundamental spending in research. And it shouldn't be, obviously, but I think it is.

Yeah, well, there's several things there.

One, I think, along with the COP process since 1992, the Framework Convention, what happened starting with George W. Bush and then Obama was a parallel process where they pulled together the major economies, like eight countries, I think, that together were 85% of emissions.

And they started having sectoral conversations. So what can we do on nuclear? Or what can we do on carbon capture? Or what can we do on efficiency to make progress together? And it's so much more sensible to think about sectors like the industry. You know, one of the hard to evade areas is is heavy industry and smelting and all that stuff.

And the more you can have focused conversations among countries that are responsible for the vast majority of that, the more likely you are to move the whole process forward.

And they were parallel, informal, not part of the UN process. But helping to facilitate it and having those conversations with China, I think has helped. And of course, then more recently, we in China have all these other stress factors, which makes this harder. Taiwan and everything is going to be a super hot button kind of problem. So whether that goes forward or not, I'm not sure.

One other factor that's driving progress on that level is the extraordinary advances in remote sensing. It's been said to me, when you look at ahead of the Paris Agreement and the run-up to Paris in 2015, China issued new estimates for its greenhouse gas emissions or coal. I can't remember right now whether it was coal use or greenhouse gases. They're basically the same. And it was higher. It was higher than their previous emissions. And it's quite clear that it's because they know they can't really lie anymore.

There's websites, there are folks out there using satellite imagery to monitor the piles of coal outside of power plants and you can see the coal coming in and going out and you can make independent assessments of coal use and the like. The ability to impose transparency, and on deforestation even more so, has led to some real breakthroughs.

Just yesterday I recorded a webcast with Global Fishing Watch. This is not about climate. But, you know, they're able now using direct satellite measurements and ship transponders to really get a picture of illegal and legal fishing and other industrial activity, including offshore wind and oil emplacements and stuff. And the more of that, the better. And that builds sort of an ecosystem driving change.

First of all, there'd be more of a transparent sense of what's real.

And second, they'll have done more that they can then report and pledge to do at these meetings.

I've been writing about this since COP Zero, since the Framework Convention, and since before then, since 1988, the first conference on the changing atmosphere in Toronto. And I think in the early days I absolutely felt, like many, that because of the CFC treaty, the ozone treaty, and things like the Clean Air Act, that some top-down structure would emerge that would help, that would force or prod the world to behave better. And it became clearer and clearer as the years went by and that decarbonization graph went on its merry way, and countries came and went, and pledges came and went, and numbers came and went, whether it's 350 ppm or 2 degrees, 1.5 degrees. The treaty process, essentially all these meetings are doing is enshrining what countries have already decided they're willing to do. I think the key thing is to remember this is a process that's descriptive, it's not determinative.

Yeah, and that's not bad! It’s really disappointing if you’re looking for a determinative process, but a descriptive meeting on climate progress is really valuable.

Yeah, right. By the way, another great example, not just of transparency, but just of shifting a model of governance, was in the 80s, this toxics release inventory was created. And it's where companies have to list their emissions, you know, like pollutants, whatever's coming out of your smokestacks or your drain pipes. And it's clear that just having to list the stuff prompted change. And this has spilled over into developing countries too.

Long, long time ago in Indonesia, there was some project and I can't remember, it was just Jakarta, but it was, I think the acronym was P-R-O-S-P-R, PROSPR. And it was a reporting process. And these factories and stuff were saying, oh, well, you know, we're letting all this chlorine go.

Why don't we, we could collect that and sell it. You know, so it creates a cultural reality that emissions and releases and pollutants are something that in your corporate interest, you want to deal with, you don't want to just let it flow.

And so the TRI, I think, is a good example of a different kind of model where transparency and just going through the kind of calisthenics of having someone who runs around measuring your stuff can create change too.

One thing this reminds me of too, stepping way back in 2007, Steve Schneider, one of the early climate scientists from the 70s and 80s who passed away too soon, He spent a year in Australia as some visiting scholar and he gave us a talk there and I wrote about it in 2007 where he talked about the importance of starting small, starting with steps that are implicitly interesting and the communities can understand. I mean, he used some example like putting a greenhouse using the CO2 from a power plant or something. But he was using that just as a thought experiment. He said, if you do, you start with these pilot projects, and you can then build momentum toward much bigger changes.

And I think again, the IRA is stimulating a lot of communities. From the scale of neighborhood having heat pumps pop up on the outsides of houses, to the more communities are communicating to their neighbors, the more you can build from pilot scale, discreet little successes toward a real significant change, especially through the course of a decade. Assuming the Republicans don't get back in office and try to squash the IRA, which I think will be hard because most of the assets I think are going to Republican districts.

Exactly. Like I think one really heartening trend, like you said, is Iowa getting most of its electricity from wind, Texas becoming a gigantic renewables hub.

I think that we can win the fight on climate change, at least the part that can take place in our lifetimes, the major switch renewables, without winning the argument.

We’re already starting to see this, but I anticipate that in 2040, there will be like rock-ribbed conservatives who will like “screw the environment, screw liberal regulation,” and they'll be driving electric cars and all their electricity will come from solar power, because that'll just be the most sensible economic measure.

The things environmentalism has to offer, like restrictions on pollutants, clean air, clean water, better alternatives like LEDs for incandescent bulbs or solar plus batteries for coal plants, the alternatives are just better. And that's, I think, what the focus needs to be on, on developing and promoting better alternatives, not calling for sacrifice.

Because if you call for sacrifice, you lose.

I talked to a climate activist in France last year who said, I'm campaigning to limit everyone to one round-trip plane flight in their life. And I'm like, I see your justification in the carbon math, but do you realize even if you magically get that passed, your party will lose the next election, and then you will have tainted the climate movement by association forever?

I feel like a shift towards abundance, not sacrifice and meeting people where they are and not asking for people to really change their values is the way we get big action on climate change.

Yeah, and there are limits. I think there do need still to be sticks and there will always be sticks. Methane is an arena where the combination of improved remote sensing and actual regulations is making a difference and can make a difference going forward.

And that's great! I'm not against that. I totally support that.

I do too. And that gets back to what I was saying earlier about, you know, there is a role for activism still. I've criticized some of the more extreme steps that some have taken because I think they're counterproductive. But I think regulation does still play a role here.

And what's weird, too, is Yale and some partners have done these nationwide surveys at the county level of people's attitudes on climate change, on solar, on all the other dimensions of the question, and they find that there's no red and blue states when it comes to the most important issues, including regulating CO2 as a pollutant. On the street, when you just ask people, should carbon dioxide pollution from power plants be regulated? Even in red states, you get a mix of answers, and quite often it's most people. So there is that too. And I think that's because people recognize ultimately that some pollution is, you know, pollution is a bad that isn't always going to go away just based on people saying they promise to do something.

Absolutely. So this has been a fascinating conversation. We're coming up on the hour mark. I just want to make sure I'm respecting your time. Can we keep talking or do you need to move on?

We can talk a little longer.

So, yeah, I agree with you. And I am just feeling more hopeful on climate issues, especially since the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, than I ever have in my life. And I guess I want to ask, given your longer experience, how are you feeling about the future?

Overall, I still have a diurnal pattern where I wake up optimistic and go to bed kind of bummed out, whether it's about the fate of the North Atlantic right whale or climate change.

I feel on climate, I think we're doing a good job. I think the wild rumpus is pushing us in the right direction. There's limits to how much we can change about the global energy menu. It's sort of got this, it is what Timothy Morton, a scholar philosopher talks about as hyper-objects. There are things that are fundamentally different than we perceive them to be. We look at it because we grew up with pollution and we think, oh, CO2 is a pollution problem. And then you realize, oh my God, it's all these things. It's a political problem. It's a technological problem. It's every problem. And that can be paralyzing.

But, as I said, that long multi-century graph of slow decarbonization is happening.

So what I end up thinking most days as I look at this mix is, is some worry. Many activists look out the window and see wildfires and flooding and say, oh my God, oh my God, climate change.

And then they run into the streets with this, you know, trying to change the system. Which is, you know, I'm not saying don't do that, but I'm saying that the climate problem that you perceive is often very different than what you imagine.

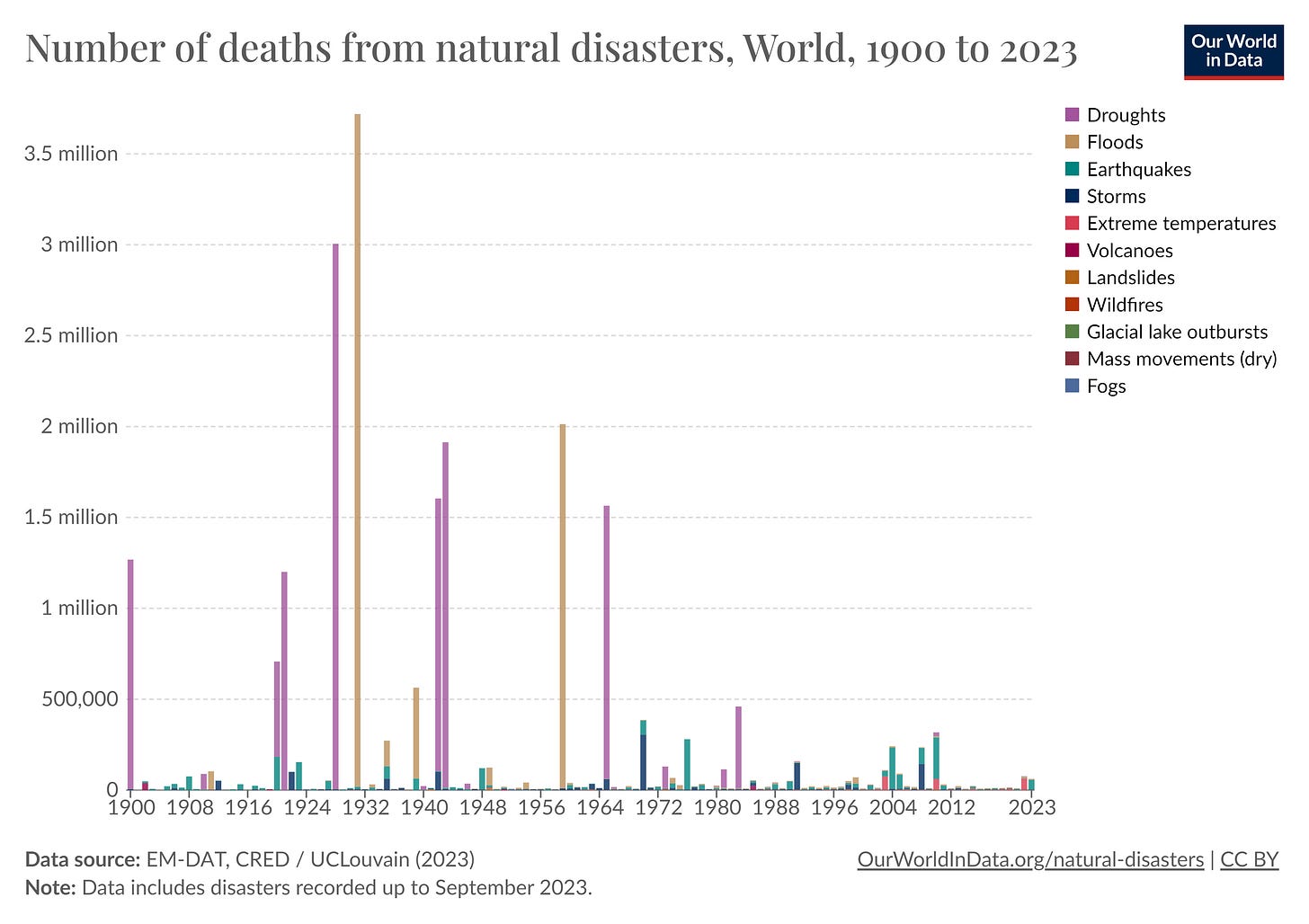

So much of what we see when we look at a fire or a heat wave and look at the impacts or a flood is from factors on the ground. We have extreme heat and extreme cold and the heat waves are getting fundamentally hotter. That's something that where climate change signals are very strong. But when you look at the losses, the key thing that we all care about as humans is risk and loss, right?

Economic damage is going up, but human deaths are going down!

Yeah, and economic damage is going up mainly because we built too much shit in places that are vulnerable. It's not because of global warming. You should do a conversation with Roger Pielke Jr. at the University of Colorado, he’s written so many peer-reviewed papers for decades on disaster loss.

There's dozens of researchers in this field who say you're missing a key factor. Looking at that only with a climate change lens means you're missing what geographers call the expanding bullseye. Yeah, the world every year is filled with hazards.

There's fire, there's flood, there's tornado, there's coastal surge like we just had here in Maine that took away our dock forever. And so if you're looking at those impacts, the impacts, the losses, and you think climate change is the thing you need to work on, you're missing the fact that what's called exposure and vulnerability. We have created a huge amount of exposure. to today's hazards and vulnerability is about, well, who's dying in heat waves? It's elderly people who can't afford to turn on their air conditioner. It's homeless people in the street who are there because of socioeconomic realities.

And what houses are burning? I wrote in depth about the Boulder County, Colorado fires, terrible fires. Those towns were built out of wood in communities that didn't have to hew to the Boulder County fire code because they're independent municipalities. And so they built with wood and with a building code that didn't integrate fire risk. And lo and behold, you have a very windy day and a lot of grassland. And these fires, you know, super spread through into these communities. So that's vulnerability and exposure you built. Stephen Pyne, P-Y-N-E, a great fire historian, told me essentially when you do that, you're you're moving a forest, by building a wooden community,

You're missing all the things that can be done on the ground. Christy Ebi, E-B-I. She's at University of Washington. She's one of the world's experts on heat and climate. I did a great chat with her. And she says straight out, and she's said this many times, nobody needs to die in a heat wave. She's like the most published scientist on heat and health and climate.

People just go, climate change, climate emergency, heat, heat, heat. And they're not thinking, well, who's down the street from me who's more vulnerable than I am, who I can help to withstand this?

And if we work more on those things, more on vulnerability reduction and examining our expanding bullseyes, whether it's in Florida or in wildfire zones, or even here on the coast of Maine, the more we have the capacity to get through the next few decades, and the century, while we work on the carbon problem with way fewer impacts from climate hazards.

It's doable and that's the optimism in me, my determination is to fill that gap. I did a piece two years ago plus on my blog saying what's perceived as a climate emergency is really mostly a vulnerability emergency. So that's the stuff that I'm optimistic about.

The stuff that does worry me is we are changing the atmosphere and the ocean's chemistry in ways that will be profound for centuries, even millennia to come. And geoengineering, we could do a whole nother show on that. It's going to have all kinds of issues, procedural and philosophical and other issues that will impede that.

But I think also if we sustain human capacity for intelligence and applied intelligence, and innovation and connectivity and empathy, especially empathy, because that's how you reduce vulnerability, then we can thrive for a long time to come.

Absolutely. I agree. And for long-term habitability, I am just really encouraged by, you know, long-term habitability looked a lot more at risk 20 years ago when RCP 8.5 looked realistic. We're talking about essentially a millennium scale problem, and in just a couple of decades, we've made incredible progress.

That’s a powerful quote, applied intelligence and empathy, that's a really good way of summing up what we do need to deal with a lot of the things facing the world.

So thank you so much, Andy. I really appreciate that.

Yeah. The last thing I'll add is a fundamental component of that is communication. And not just, you know, my first global warming cover story in 1988, was the old model of communication. You know, it's a blazing earth melting on a hot plate. That was the illustration. And that's not what we need now.

What we need is communication, innovation, and facilitation at every level between disciplines. Social and physical scientists need to talk to each other more. Climate modelers and field climate scientists need to talk to each other. And scientists need to talk to their communities more. And I don't just mean on social media. I mean, go to your town meeting just as a person and say here I am, I live here. And then communities need to talk to each other about and we need to communicate with our neighbors so that you know who's vulnerable to heat.

And the role of the internet is vital. You know, you and I are having a conversation through our glass screens here, and the world is a better place because of it, I think. In some tiny way, someone will see this.

And I've had this experience where young people, through my career, have said, they changed or they chose a career path because of something I wrote.

I think I'm one of them. I was really inspired by your book The North Pole Was Here when I was a kid.

Oh, you mentioned that, which is cool. You know, I could have written that and probably should have written it as a book for adults. But there was an opportunity to write it for sort of young adults.

And by the way, finally, the most important innovation in communication is listening. Pete Seeger, my folk legend friend, while he's singing, he's always doing this [holding his ear].

I'll send you the clip of Jigar Shah and my conversation, because he summarizes it in literally one minute. This opportunity, this crystalline opportunity, it's a magical moment.

This Crystalline Opportunity. That would be a great name for a publication or a substack about implementing climate action.

Good. I'll send you that clip.

So thank you so much and thank you for recommending The Weekly Anthropocene and helping me grow my writing. Because I am trying to push things in the direction we've been talking about, towards interdisciplinary collaboration and towards thinking and towards solutionism, not apocalypticism. Thank you.

All right, you take care. Yeah, thank you. Thanks for doing that.

Share this post