The Weekly Anthropocene: Alexander von Humboldt

The Father of Environmentalism you've never heard of

This article is a brief introduction to the life and work of Alexander von Humboldt, a really cool historical figure that more people should know about. Perhaps the most interesting point here is that two hundred years ago, an educated person in America or Europe would have been shocked that such an article was required. Humboldt was, in the first few decades of the 1800s, incredibly famous, widely known as the second most famous person in the world (after Napoleon), renowned worldwide a scientist-explorer-superhero at the cutting edge of fields from geography to geology to biology to physics. He essentially created the field that would come to be known as “ecology,” and popularized the Ancient Greek word “cosmos,” the title of his masterwork, to describe a unified scientific conception of the universe.

Thomas Jefferson called him “one of the greatest ornaments of the age.” Charles Darwin said “nothing ever stimulated my zeal so much as reading Humboldt’s Personal Narrative.” Simón Bolívar called him the true “discoverer of the New World.” And Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the great German poet, said that spending a few days with Humboldt was so fascinating, it was like “having lived several years.”

More species and places are named after Alexander von Humboldt than anyone else in history. A partial list includes the Humboldt squid, Humboldt penguin, Humboldt's hog-nosed skunk, Humboldt’s sapphire hummingbird, Humboldt Current in the South Pacific, Humboldt Glacier in Greenland, Humboldt County in California, Humboldt Park in Chicago, Humboldt national parks, forests, or monuments in Cuba, Peru, and the United States, Humboldt Peak in Colorado, three different Humboldt mountain ranges (in New Zealand, Nevada, and Antarctica), the Humboldt River in Nevada, towns named Humboldt in eight US states and one Canadian province, universities named after Humboldt in four different countries, Mare Humboldtianum on the Moon and the mineral humboldtine. The U.S. state of Nevada was almost named the state of Humboldt at its constitutional convention in 1864.

On September 14th, 1869, the 100th anniversary of his birth, cities worldwide held Humboldt-themed celebrations, with U.S. President Ulysses Grant attending a 10,000-person Humboldt-fest in Pittsburgh concurrent with a 25,000-person Humboldt celebration in New York and an 80,000 person event in Berlin.

So who was Alexander von Humboldt, and why was he so awesome?

Almost all non-linked Humboldt facts in this article are from the excellent book “The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World” by Andrea Wulf.

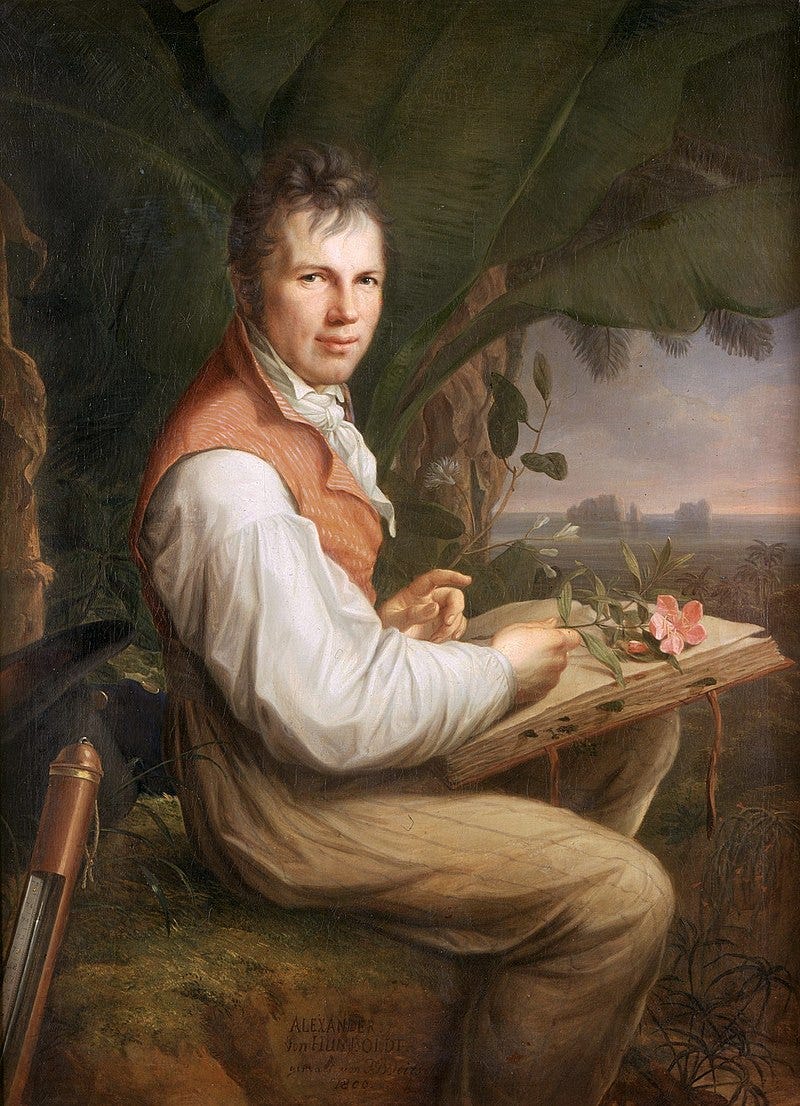

Alexander von Humboldt was born in 1769 to an aristocratic Prussian family that was rapidly rising through the ranks of the bellicose little Germanic kingdom’s society. The future king Friedrich Wilhelm II was his godfather and his father became chamberlain at the royal court before dying when Alexander was nine. His elder brother Wilhelm von Humboldt went on to become a major Prussian education reformer and diplomat as well as a linguist and philosopher. Alexander’s interests didn’t really have a place among the usual aristocratic pursuits: he received top-of-the-line tutors and a university education, but the “scientist” track didn’t really exist at the time (the word scientist was only coined in 1834), and he ended up studying a mix of subjects like foreign languages, mathematics, and geology, then working for the Prussian Ministry of Mines. Humboldt was constantly writing down observations of the natural world and conducting experiments (including with a tantalizing new discovery: electricity) in his spare time and stopping to meet and befriend luminaries like British botanist Sir Joseph Banks in 1790 and Goethe in 1794.

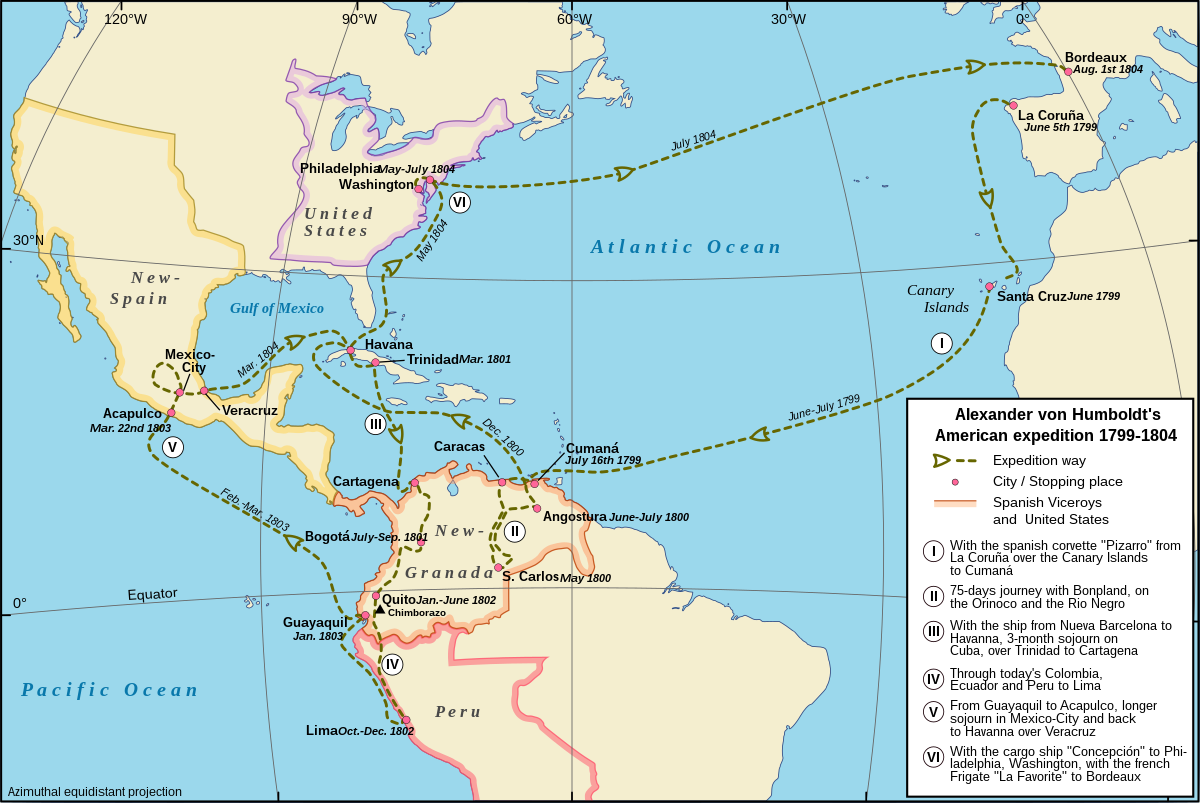

The event that really launched Humboldt’s career was his expedition to the Americas (mostly in different parts of what was then the Spanish Empire) in 1799-1804. A whole bunch of really interesting stuff happened on this trip (most of which would later be made public in Humboldt’s writings in following years) so instead of going for a comprehensive or even fully cohesive description, here’s a bulleted list:

Shortly after his arrival in what is now Venezuela in July 1799, Humboldt visited the Guácharo Cave and wrote the first formal description of a species new to science: the nocturnal, echolocating, bat-like oilbird (Steatornis caripensis).

In November 1799, when the city of Cumana (where he was staying) was struck by an earthquake, Humboldt timed the shocks and took notes about the ripples’ direction.

From February to August 1800, Humboldt and French botanist Aimé Bonpland (his fellow traveler through much of this five-year period) embarked on a perilous inland expedition to investigate the Casiquiare river, a unique natural canal linking the Orinoco and Amazon watersheds. Humboldt made the first detailed map of the Casiquiaire, shedding light on a region previously unknown in Europe.

In February 1800, at a stopover on Lake Valencia in Venezuela, Humboldt became the first known person to even speculate about human-caused climate change, writing “When forests are destroyed, as they are everywhere in America by the European planters…the springs are entirely dried up, or become less abundant.” In full, his writing discusses the now-common knowledge that forest vegetation helps hold soil together and prevent erosion and flooding. This was a new idea at the time. Later he would write “The wooded region acts in a threefold manner in diminishing the temperature; by cooling shade, by evaporation, and by radiation.” The idea that trees are good is so mainstream now that it hardly seems to have needed to be invented, but at the time this was brand-new thinking: most European thought prior to Humboldt describes forests as alien, dangerous “wastes.”

In March 1800, Humboldt and Bonpland encountered electric eels and conducted an array of experiments on them for four hours (often involving shocking themselves).

In spring, as their expedition reached the rainforest, Humboldt encountered and wrote about jaguars, river dolphins, and capybaras, and almost killed himself when he accidentally touched curare, later becoming the first European to describe how the local tribes prepared it as a poison for their blowguns. Humboldt and Bonpland also sustained themselves on wild-growing Brazil nuts, which Humboldt subsequently introduced to Europe.

After returning to Cumana, in November 1800 Humboldt sent two parcels of seeds he had collected on his travels to Sir Joseph Banks for Kew Gardens.

Sailing to Havana in December 1800, Humboldt became known as “the second discoverer of Cuba” due to the writing, surveying, and research he conducted on the island during a three-month stay. His later (1826) book about Cuba also included strong criticisms of slavery, so it was suppressed on the island that was its subject.

From April 1801 to January 1802, Humboldt and his traveling companions crossed the Andes overland, an extremely remote and arduous trek at the time, traveling from Cartagena in modern Colombia to Quito in modern Ecuador.

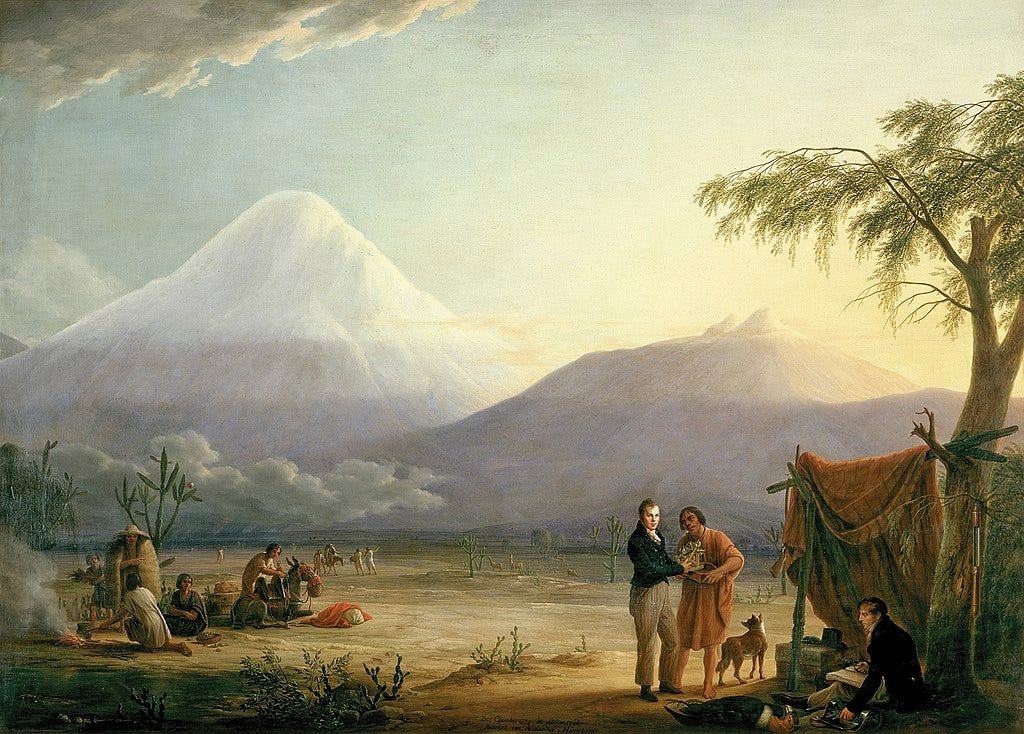

In Quito, he stayed for a while and used it as his base to “climb systematically every reachable volcano.” This was also where he met the handsome aristocrat Carlos de Montúfar, son of the provincial governor, who became his traveling companion and probable boyfriend until he left the Americas (contemporary accounts refer to him as Humboldt’s “Adonis.”) Montúfar would later become an influential figure in the Ecuadorean independence movement.

In June 1802, he climbed Chimborazo, the Ecuadorean volcano then thought to be the world’s highest peak. Humboldt didn't make it to the summit, but did reach an altitude (measured with a barometer) of 19,413 feet. At the time, this was higher than any human had ever been: not even the early balloonists had reached this altitude, and this ascent made him a world-leading mountaineer.

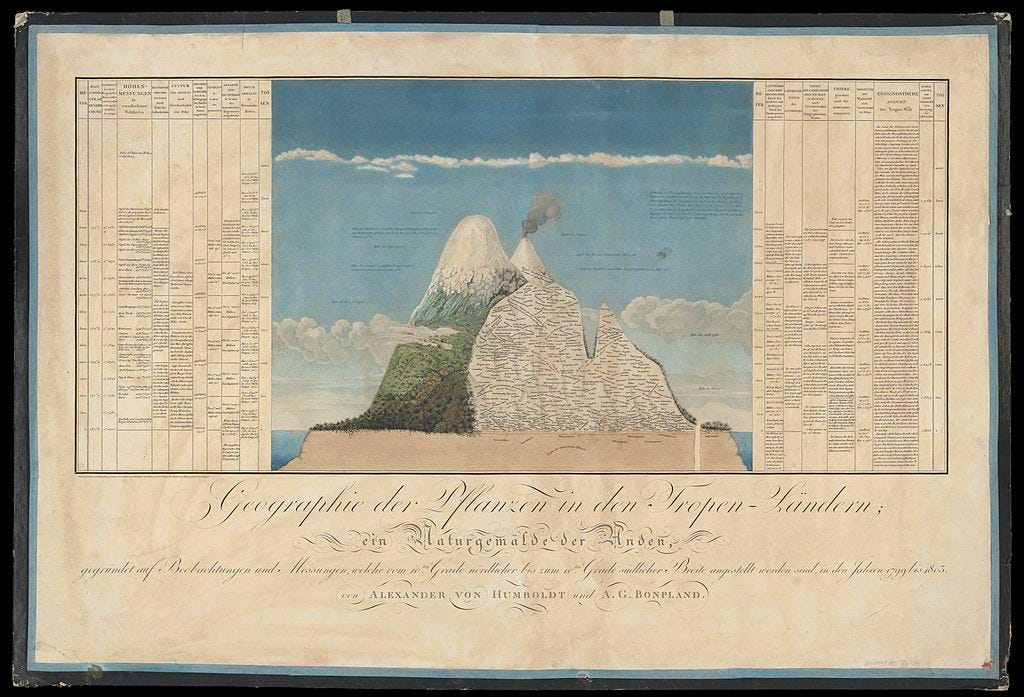

On the way down from Chimborazo, Humboldt began sketching his “Naturgemälde,” an annotated visual display of altitude, temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pressure data alongside the different vegetation, animal life and ecosystem types present at different altitudes. This was a then-unprecedented way of displaying data visually, and is one candidate to be considered the world’s “first infographic.1”

In fall 1802, sailing north from Lima to Guayaquil, Humboldt took measurements and noted the unusual coldness of ocean current below them. This early scientific record would later lead to it being named the Humboldt Current, a major nutrient-rich circulation supporting a highly productive marine ecosystem.

Humboldt spent much of 1803 in Mexico, where he wrote an acclaimed report on silver mining, studied the recently rediscovered Aztec sun stone, and examined records of pre-Columbian civilizations in the colonial archives. This would lead to his later 1810 work examining the Dresden Codex, one of the very few remaining books written by the Maya civilization2, and publishing the first reproduction of its pages. Humboldt argued that the Maya were in fact a complex and scientifically advanced civilization (citing their profound astronomical knowledge), revolutionizing Europe’s understanding of American indigenous peoples.

On June 2, 1804, Alexander von Humboldt met incumbent U.S. President Thomas Jefferson at the White House3, giving him nineteen pages of data-filled extracts from his notes, with a special focus on the then-disputed area between Mexico and the United States that now comprises much of Texas. (This was new and valuable info at the time, when a top priority of the US government was gathering more knowledge about the western reaches of the continent. The Louisiana Purchase had been concluded in 1803, and Lewis and Clark had just set out in May 1804). Jefferson held a Cabinet meeting a few weeks later to discuss how this intelligence should influence their ongoing border negotiations with Spain.

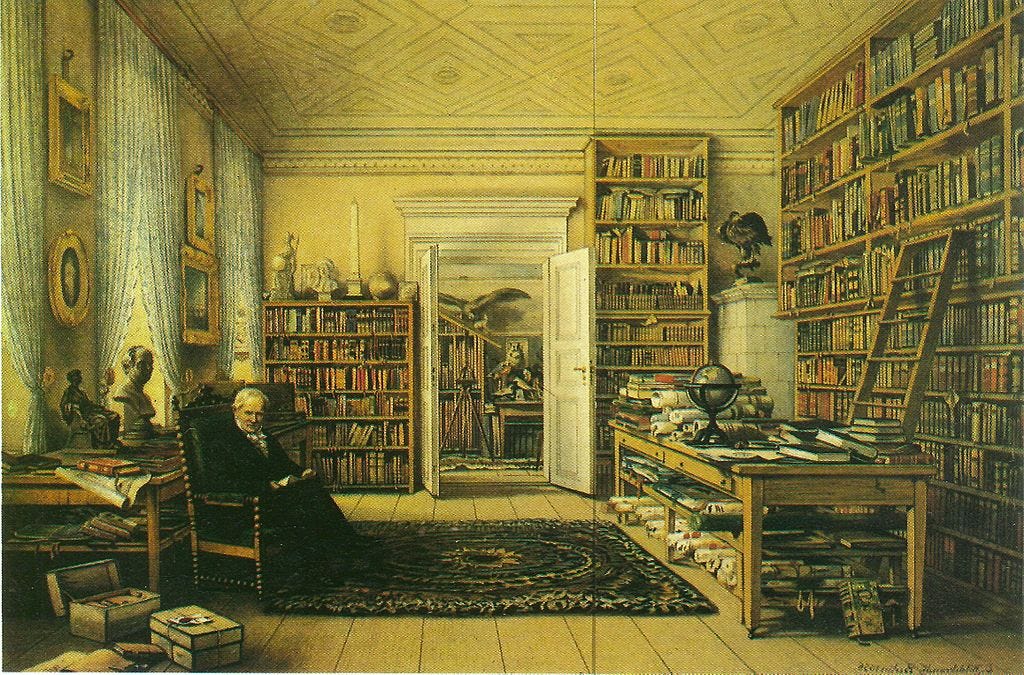

Humboldt basically spent the next 24 years of his life (1804-1829) writing dozens of widely acclaimed books about his travels and his scientific ideas (many of which are now available online for free), bouncing between the salons of Europe, and becoming the most well-known and widely respected “natural philosopher” of his time. There are many great stories about the stuff he got up to in this time period; here are just three.

On September 16, 1804, just a few weeks after Humboldt returned to Paris, a brilliant young physicist, chemist, and balloonist named Joseph Gay-Lussac broke his Chimborazo record for “highest human being ever” by ascending to 23,000 feet to collect data on temperatures, pressures, and magnetic fields at that altitude. Within a few months, Gay-Lussac and Humboldt were giving lectures together around their experiences at high elevation. In 1805, they published a new fundamental chemistry discovery together: that water was composed of two parts hydrogen to one part oxygen. Within a few years, they were travelling around Europe together, living together, and sharing a bedroom4. The modern French and German governments award the Gay-Lussac–Humboldt Prize to German and French scientists (particularly those cooperating between the two countries) in their honor.

When Humboldt was living in Paris in 1805, he became a close friend of Simón Bolívar, then a dissolute Spanish-American aristocrat from Caracas living it up in Europe to drown his grief over his wife’s death from yellow fever. After intensely discussing South America with Humboldt for months (in fact, just after running into Humboldt and Gay-Lussac on their own Italian trip) Bolívar made the famous “Oath of Monte Sacro” in Rome in August 1805 where he pledged himself to the cause of South American liberation, leading to his extraordinary political and military career in the South American revolutions of 1811-1830. There aren’t great records of everything Humboldt and Bolívar talked about, but it seems clear that Humboldt was a key figure in the life of El Libertador.

Humboldt’s seven-volume Personal narrative of travels to the equinoctial regions of the New Continent, during the years 1799-18045 became a massive, worldwide hit, quickly becoming a worldwide bestseller and inspiring a generation of naturalists. In particular, it directly inspired a twenty-two year old Charles Darwin in 1831 to undergo the most important journey of his life. Darwin wrote “My admiration of his [Humboldt’s] famous personal narrative (part of which I almost know by heart) determined me to travel in different countries, and led me to volunteer as naturalist in her Majesty’s ship Beagle.” Darwin was intensely inspired by the Personal narrative, and carried a copy with him in his tiny cabin on the Beagle, where he made the famous observations of Galapagos finches that would lead to his theory of evolution. (Some of his earliest evolution-related ideas are evident in margin notes scribbled on his copy of the Personal narrative). When Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle came out in 1839, Humboldt sent him a letter of praise and wrote an enthusiastic public review.

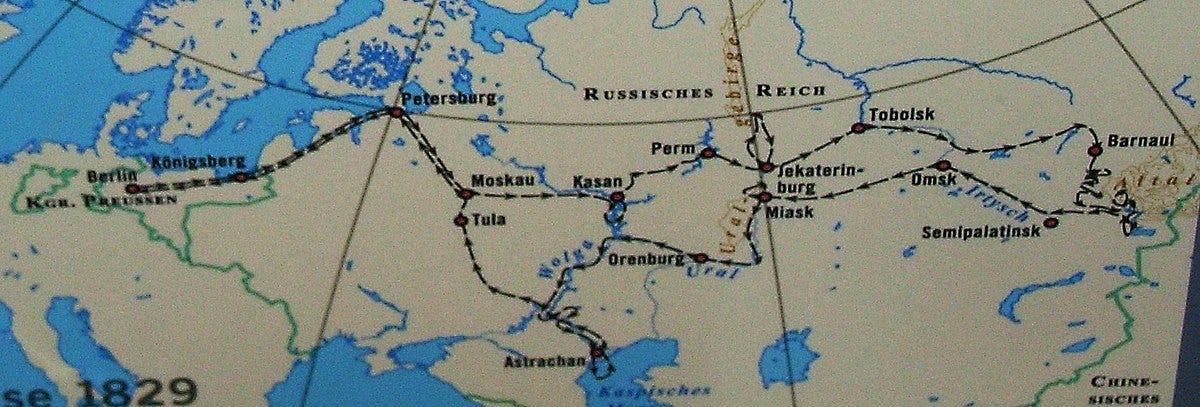

In 1829, Humboldt embarked on his second great expedition, though it was much shorter than his American odyssey. Under the patronage of Tsar Nicholas I’s Russian Empire, Humboldt led an expedition into the depths of Central Asia, from Berlin to the Altai Mountains and the Chinese-Mongolian border. Humboldt himself didn’t put as much focus on this expedition, only writing two shorter books about it, but there were still some very cool aspects.

Recognizing similar geology in the Urals to diamond-bearing regions he had observed in the Andes, Humboldt insisted that there were diamonds in Russia. This was considered crazy at the time because no diamonds had ever been found outside the tropics. A member of his expedition named Count Polier split off from the group to inspect a Yekaterinburg mine on July 1st, 1829, and told the men to follow Humboldt’s recommendations on where to search for diamonds. They found the first diamond in Russia a few hours later. (This kind of thing was why major governments were paying Humboldt large amounts of money just to visit their territory; he’d already substantially improved Prussian mining conditions and practices as a local official in the 1790s and given valuable advice to Spain on their silver mining in Mexico in 1803-04).

On September 14, 1829, Humboldt happened to celebrate his sixtieth birthday with the man who would become Lenin’s grandfather (which of course nobody knew at the time), a local apothecary in the little mining town of Miass.

Humboldt criticized overuse of water resources for irrigation in Siberia (highly prescient, given the 20th century’s Aral Sea disaster) and in one of his books about the expedition listed deforestation, irrigation, and industrial facilities’ production of “great masses of steam and gas” as three major ways in which humanity was affecting the climate. Before even the greenhouse effect had been fully described (by Eunice Newton Foote among others), Humboldt had an inkling that fossil fuel emissions might, somehow, be causing global climate change.

In late 1829 in St. Petersburg, having returned from the expedition, Humboldt gave a speech at the Imperial Academy of Sciences calling for a massive global scientific collaboration to discover more about Earth’s magnetic field, kicking off the establishment of a chain of global observatories and the years of coordinated study that became known as the “Magnetic Crusade.”

After his Russian expedition, Humboldt devoted years to a new great work: the five-volume Cosmos6: A Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe. The book’s ambitions were immense: nothing less than a comprehensive description of all of humanity’s knowledge about the physical universe7. When published, starting with the first volume in 1845, it became another sensation, influencing scientists around the world and literary writers from Walt Whitman to Henry David Thoreau.

It took the rest of his life to write: Humboldt died in May 1859 at the age of eighty-nine, less than a month after sending the fifth volume of Cosmos to his publisher. He had revolutionized humanity’s understanding of nature and the physical world, changed the course of history, and seen and done things that no one ever had before him. His life was amazing, and more people should know about his adventures, his discoveries, his ideas, and his legacy. Now you do!

For fellow historical data visualization fans out there: yes, this was before both Charles Minard’s famous map of Napoleon’s 1812-1813 Russian campaign and Florence Nightingale’s charts (published in the 1850s and 60s) of British army casualties in the Crimean War.

Humboldt found this book in Germany, not in Mexico, where it had ended up after being presented to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in the 1500s.

It was then known as the Executive Mansion, but it was already white, despite the popular misconception that it was painted white to hide fire damage after the British burned Washington D.C. in August 1814.

Which didn’t necessarily indicate a romantic relationship in the culture of the time, but…this writer is kind of rooting for them! It would be so cool if two subsequent high-elevation-ascending record-holders who then discovered the composition of water together were a couple! At the very least, it was a really awesome friendship.

Book title conventions were different then.

The term “cosmos”, now common, was essentially coined by Humboldt from Ancient Greek roots at this time to refer to a scientific description of the universe.

This book was highly radical in attempting to describe everything in the universe but never mentioning religion or a “creator God,” essentially becoming the foundational text for a wholly scientific view of reality. So…Humboldt more or less invented both modern environmental science and modern secular humanism? That sounds like an absurdly bold claim, but there’s pretty strong evidence. (Admittedly there were many other fascinating scientific works by proto-secular humanists before this, such as Denis Diderot’s revolutionary Encyclopédie, but Humboldt’s Cosmos was the first that really brought together scientific explanations for the physical state of the universe without resorting to religion).

Wonderful article. I agree. What a stellar polymath in his age of generalists when there was still a chance that one person could encompass the bulk of "natural science" You've done us all a service in bringing this figure back to our attentions! Humboldt seems truly inspirational.

This is the most fascinating article you have written thus far, kudos to you for your research and for reawakening interest in this remarkable scientist and visionary.