After visiting the Pavagada solar park, I spent the afternoon of May 15th through the dawn of the 20th in and around the city of Mysuru (historically known as Mysore) writing several articles and exploring local historical sites. The fascinating history of Mysore really deserves a quick summary to give context to my sojourn there, so here goes!

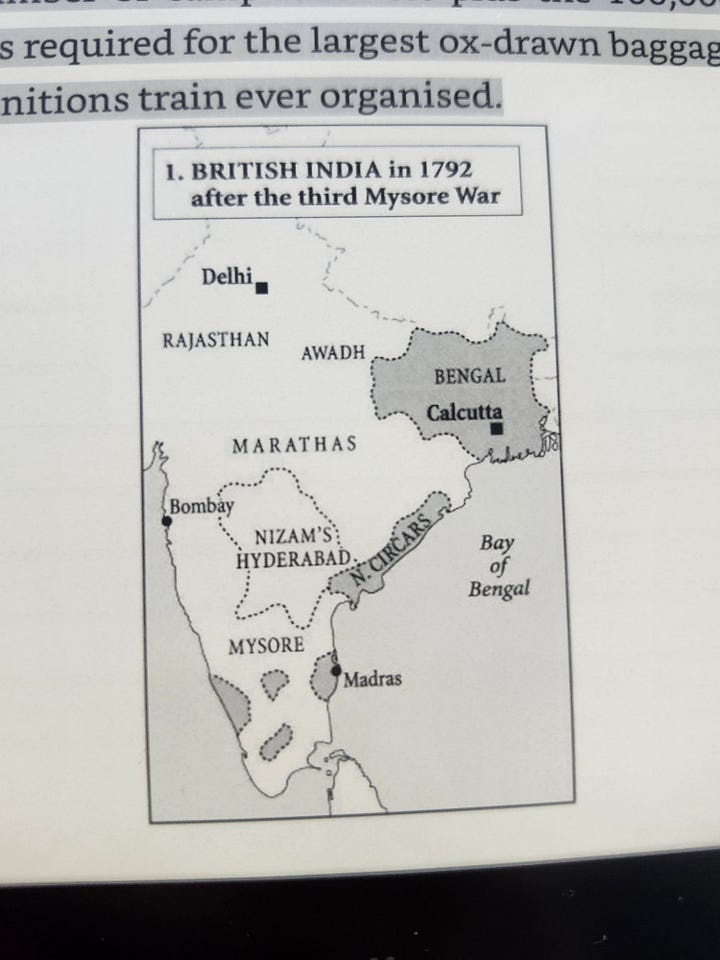

Founded in late-medieval India as one of many independent South Indian polities and ruled by the Wadiyar (or Wodeyer or Wodeyar1) dynasty for centuries, Mysore attained global prominence in the second half of the 1700s as a regional rival to the British Empire for hegemony over South India. By the 1760s, military commander Hyder Ali (or Haider Ali) essentially ruled the kingdom of Mysore, with the Wodeyar monarchs kept on as powerless figureheads in a fashion very similar to the contemporary Japanese shogunate. The British East India Company was rapidly expanding from the trading ports of Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta to effective control of large swathes of India this period, with Clive establishing British hegemony of Bengal (now Bangladesh plus the Indian state of West Bengal) roughly from 1757 (Battle of Plassey, the defeat/coup of the pro-French Bengal ruler) through 1772 (establishment of direct Company rule over Bengal). Hyder Ali’s Mysore (increasingly an ally of the French as well) was also expanding, conquering much of the Malabar coast, now part of the Indian state of Kerala.

The stage was set for conflict, and conflict duly arrived in the form of four Anglo-Mysore Wars, from 1767-69, 1780-84, 1790-2, and 1798-99. The first war was basically a draw and a return to the status quo ante bellum, but the second saw Mysore successfully fend off all attacks and dictate the terms of the resulting peace treaty. The reason why became clear as early as the Battle of Pollilur in 1780, when an army led by Hyder Ali’s son Tipu Sultan2 (or Tippu or Tippoo) subjected the East India Company army to a crushing defeat thanks to use of an incredible new technology: rocket artillery.

By the late 1700s gunpowder and fireworks had been around for centuries, and single-shot muzzleloader muskets and cannons were now the common equipment of war, but Mysorean engineers were the first to create iron-shelled war rockets, effectively directing the trajectory of a gunpowder explosion by trapping it in an aerodynamic casing of hammered iron. These early visions couldn’t be aimed that well, but it turned out that if you launched enough of them in broadly the right direction it didn’t matter. The military applications were immense, and a fearsome corps of Mysorean rocketeers, bearing iron rockets launched from bamboo sticks, would bedevil the British throughout the 1780s and 1790s, with Mysore retaining independence and domestic rocket-manufacturing capabilities while being increasingly courted as a key ally by the French.

The end of the fourth and final Anglo-Mysore War came with the 1799 Siege of Seringapatam, widely described as the key moment when the British truly became the rulers of India. At the time, Seringapatam (it’s called Srirangapatna today) was Tipu Sultan’s capital, a walled fortress-town on an island in the Kaveri River just outside the city of Mysore proper.

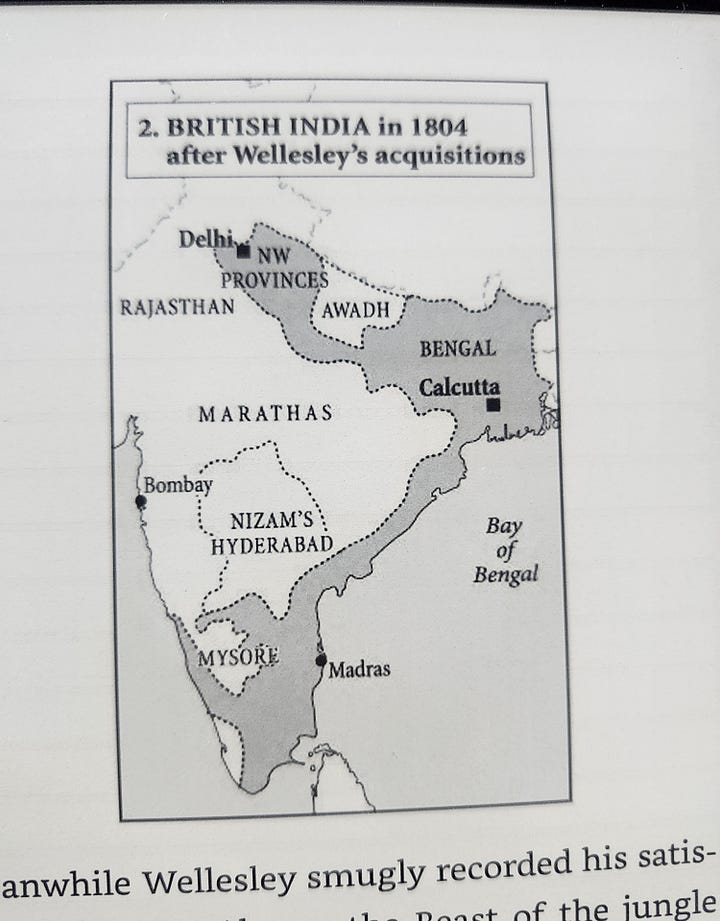

British victory led them to annex large swathes of southern India, including all of Mysore’s coastline. From 1799 through 1950, the remnant Mysore would be ruled by maharajas of the Wadiyar Dynasty (restored to power due to Maharani Lakshmi Devi siding with the British against Tipu) as one of the largest of the Indian “princely states,” essentially semi-autonomous vassals of the British Empire. After further wars with the Maratha Confederacy and the Sikh Empire, Britain directly or indirectly ruled the entire Indian subcontinent by the 1850s.

The more I looked into this period of Mysorean history, the more I found surprising and fascinating connections and resonances.

In 1781 at Trenton, New Jersey, American revolutionaries drunk a toast to “The great and heroic Hyder Ali3, raised up by providence to avenge the numberless cruelties perpetrated by the English on his unoffending countrymen, and to check the insolence and reduce the power of Britain in the East Indies.” The Mysorean rulers would remain a common anti-British “meme” in early American political discourse for decades, before being gradually forgotten.

In 1788, Tipu Sultan sent ambassadors to the court of Louis XVI to discuss an alliance, but it didn’t get anywhere geopolitically (although the Mysoreans’ exotic styles did end up influencing Parisian fashion), in part because the French Revolution broke out just a few months afterwards.

Later, in Napoleon’s 1798-99 invasion of Egypt, one of his “stretch goals” if it went really well was to send French troops all the way to India to link up with Tipu Sultan against the British.

Two American privateer ships, one in the American Revolution and one in the War of 1812, were named the Hyder Ally, apparently just to annoy their British opponents by reminding them of the “Eastern prince” who once defeated them. The Hyder Ally privateer of 1814 was even launched from Portland, Maine, practically this writer’s hometown!

Speaking of the War of 1812, remember the lyric “the rockets’ red glare” from The Star-Spangled Banner? Francis Scott Key was referring to British Congreve rockets being unsuccessfully used against America’s Fort McHenry in 1814. Those Congreve rockets were based on the Mysorean rockets that the British had captured, intensively studied, and painstakingly reverse-engineered4 after the fall of Seringapatam in 1799, then used to great effect against the French in the Napoleonic Wars.

When we think of colonial expansion in the early modern era, we generally think of the European power using its greater technology against other civilizations, but this is one of the many unheralded examples (the Chinese exam system perhaps being another, in a less tangible realm?) where a non-European innovation was eagerly adopted and built upon by European powers. Mysore was the first to use rockets in battle, and the British victory on Seringapatam won them an extraordinarily valuable technology transfer in addition to regional hegemony. It would perhaps be oversimplifying, but it certainly wouldn’t be entirely inaccurate to say something like “Mysore is where the rockets mentioned in America’s national anthem came from.” The Mysorean rocketry progress was truly an extraordinary moment in technological and geopolitical history.

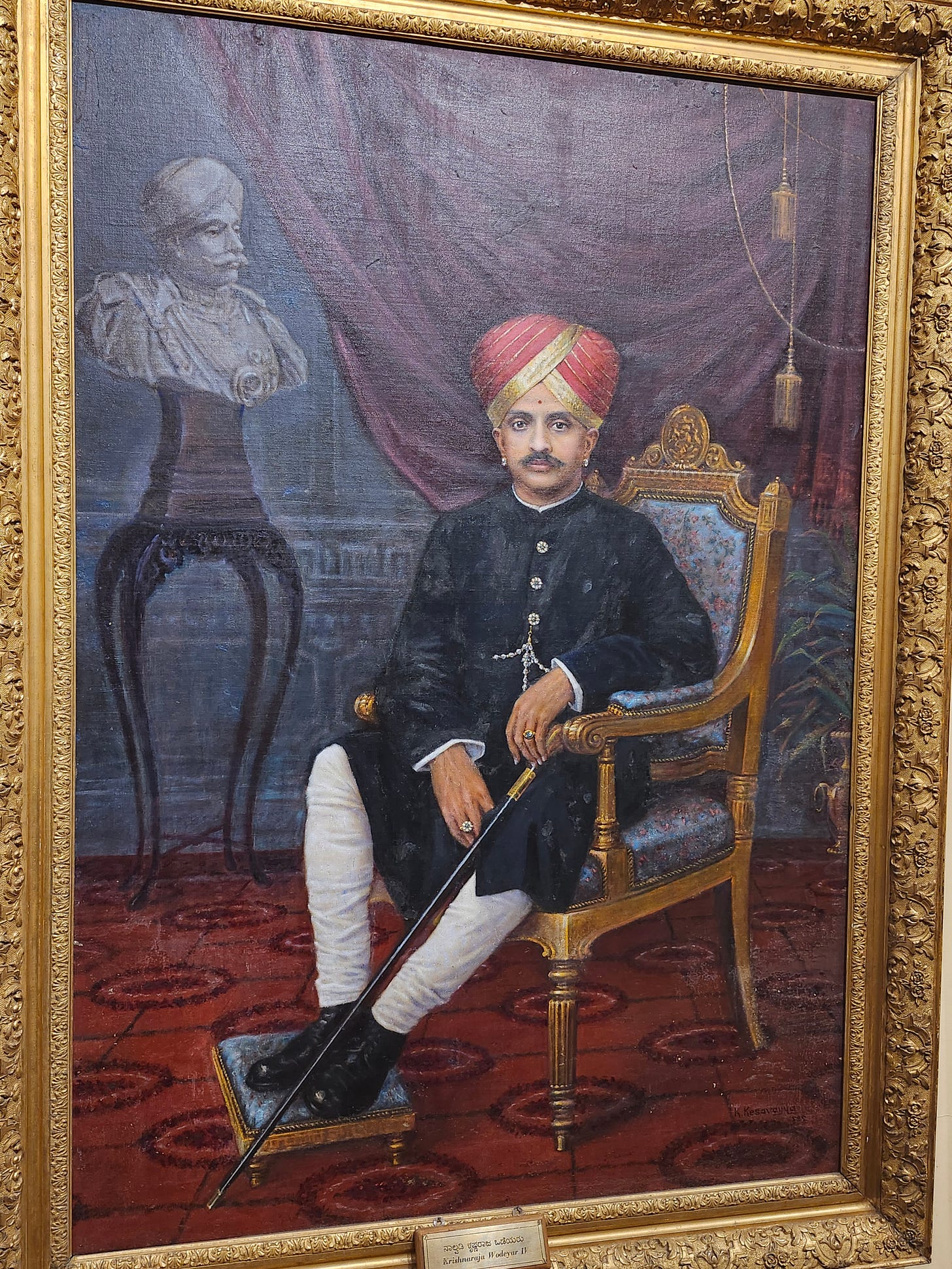

A 1700s rocketry program seems like it should be quite enough to enliven any state’s history, but it’s not the only extraordinary accomplishment of the Kingdom of Mysore. Of particular note during Mysore’s 1799-1950 “princely state” period is the reign of Maharaja Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV from 1902 to 1940. His reign would become known as the “golden age of Mysore” during which this South Indian principality became one of the most socially and technologically progressive states in the world. Here’s a quick list of a few of the highlights:

The inauguration of a hydroelectric dam at Shivanasamudra Falls5 in 1902. This doesn’t sound like a big deal these days, but at the time it was revolutionary: this was the first-ever electricity generating facility, from any source, in all of India, and very possibly the first electricity-generating facility in all of Asia!

In 1905, Bangalore became the first city in Asia to have electric street lights.

Establishment of the bicameral Mysore Legislative Council in 1907, which interestingly still exists, having evolved over the years into the modern state of Karnataka Legislative Council. Notably, women got the right to vote for this council in 1922; for context, the United States granted women the right to vote with the 19th Amendment in 1920 and France wouldn’t hold its first election with women’s suffrage until 1945.

The abolishment of legal marriage of girls below the age of 8.

Dramatically increasing the kingdom’s education budget.

Founding of the University of Mysore in 1916, the sixth university in India and the first in a princely state as opposed to directly British-ruled provinces

Building up local industries in Mysore (much as Tipu Sultan had tried to do in a completely different context over a hundred years before), including a bank, a soap factory, a silk center, a sandalwood oil factory, a steel mill, and more. In 1940, the kingdom of Mysore invested heavily in establishing an airplane company, Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) which to this day is a leading Indian aircraft manufacturer.

As all of this was happening, people around the world were raving about Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV, even in the comparatively white-supremacist 1920s and 1930s. In 1925, Gandhi (yes, the Gandhi, “Mahatma” Mohandas Gandhi) called him a raja-rishi, or saint-king. In 1930, Viscount John Sankey, incumbent Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is said to have declared “Mysore is the best administered state in the world.” In his obituary, the London Times described him as “a ruling prince second to none in esteem and affection inspired by both his impressive administration and his attractive personality6.”

Even after Mysore was absorbed into the Republic of India in 1950 and the Wadiyars were no longer a ruling royal family, this progressive legacy assured that they remained extremely popular among the local population. As I write this, Yaduveer Krishnadatta Chamaraja Wadiyar, the current “head of the family” and the guy who would be the Maharaja of Mysore if the title still existed, is currently running as the Bharatiya Janata Party candidate for the Mysore constituency in India’s 2024 general elections. The BJP appears to have won that seat by a moderate margin in the last elections in 2019, and under the controversial yet widely popular BJP Prime Minister Narendra Modi are generally considered heavy favorites in 2024, so Mr. Wadiyar’s odds look pretty good. What a historical situation! It’s kind of like if the British monarchy was disestablished, and then a few generations later you have a Mr. Windsor as a prominent candidate running for Parliament.

The first “day trip” I took during my sojourn in modern Mysuru was to the museum of Mysore Palace, built during the princely-states phase with beautiful Indo-Saracenic architecture as well as modern conveniences like an early elevator. Definitely worth seeing, but very very very crowded. If I hadn’t previously read about how the Wadiyars are still popular, this would have got me thinking along those lines: there certainly seems to still be intense public interest in their legacy.

My visit to modern Srirangapatna was considerably more variegated, though I only scratched the surface of the area’s riches. The first of the island-town’s many monuments7 I saw was the ancient Ranganathaswamy temple, sacred to a local form of Vishnu. I didn’t know this at the time, but it’s actually one of the largest and oldest surviving Hindu temple complexes in the world, and was by far the most crowd-attracting of the Srirangapatna sites I visited.

Continuing on foot, I then passed the Water Gate on the north side of the island-town, where British forces had broken through in the final fall of Seringapatam in 1799, and just a few steps later came to the stone marker indicating where Tipu Sultan had fallen in battle just afterwards. As I continued towards Tipu Sultan’s fortress, the island’s status as a religious pilgrimage site was evident at nearly every step of the journey, with garlands around sacred tree branches and a portrait of Shiva and Parvati right next to the Water Gate.

The temple had been full of people, but Tipu Sultan’s Fort appeared to be almost entirely deserted. For a good fifteen minutes, I had the crumbling layers of greenery-swathed defense walls and a lovely view over the Kaveri River all to myself. A flock of rose-ringed parakeets was harassing some black kites, squawking and dive-bombing the larger predators until they drove them off through the power of sheer annoyance. I was irresistibly reminded of the time I’d seen a group of crows displaying almost identical behavior against a bald eagle on the shores of Maine’s Long Lake; a parallel case of smaller, social, more intelligent avians working together to outwit a bird of prey. I saw two charming ground squirrels, striped like American chipmunks but much larger, chasing each other through the bushes, and a few moments later a single peacock industriously bouncing along the hillside.

Later, when passing a small group of new visitors on the way back, I observed two pigs snuffling around at the foot of one of the fort’s inner walls, and a litter of puppies were gamboling about the area. Some clever poet or poet-AI could perhaps have distilled from this tableau a Deccan version of “Ozymandias” lamenting for past glories: in 1799 your fort is the headquarters of the world’s only army of war-rocketeers, in 2024 the pigs forage beneath your walls and puppies lounge on your passageways.

I then passed by the Jama Masjid (aka Masjid-i-Ali), the mosque where Tipu Sultan had prayed just a brisk stroll away from the Ranganathaswamy Temple. I noticed a security guard at the entrance where there hadn’t been one at the temple, and some quick Googling revealed the reason why. In a local mirror of the long-running Ayodhya conflict that’s gripped India for years, some Hindu groups are demanding that this mosque be destroyed due to claims that there was once a Hindu temple on the same spot. The complex and sometimes bloodsoaked Ayodhya dispute was recently resolved in the iconoclasts’ favor, with the Babri Masjid mosque destroyed by a mob in 1992 and a new Ram Mandir inaugurated by incumbent Prime Minister Modi in 2024. Personally, I quite hope that the Jama Masjid survives: it’s heartening to have Muslim and Hindu religious sites sharing the same island.

Night was falling, and I had nearly decided to take a rickshaw home, when I noticed a “Srirangapatna Ghat” site on Google Maps. I knew that a “ghat” was a sacred river-bathing area in Hinduism, and on a whim I decided to check it out as one last point of interest to view for the day. I was richly rewarded: the ghat section of the Kaveri (or Cauvery) riverbank was lined with interesting little mini-temples along carved stone steps leading into the water. Unfamiliar birds fluttered amid the greenery, and one of the temples had a tree growing up through it to such an extent that it seemed to meld with the stone. I paused for a few moments, soaking in the scene, and to my great surprise it only took a few moments of staring at the water for me to be favored by the serendipitious arrival of an otter!

This absolutely delighted me. The otter was joyfully leaping through the water, diving and popping up and swimming and diving again in a positively entrancing manner. It was exactly the kind of playful behavior nature writer Sy Montgomery had described in her essay on New England otters. I’d seen an otter only once in years of living in New England, just after leaving my streamside tent in Maine’s Hundred Mile Wilderness, and here was one right in the middle of a crowded pilgrimage site. I’d expected this visit to Srirangapatna to be a focused immersion in cultural and historical heritage, and it certainly was that, but the river-island had managed also to furnish me with a beautiful new example of human/wildlife coexistence in modern India.

Besides these monument trips, I spent several days just living in the city, spending most of the time writing in restaurants or cafes. My visit to modern Mysuru almost felt like a mini-vacation within my trip to in India in some ways: it was by far the cleanest, most tree-covered, most walkable, least traffic-crazy, most familiar-feeling part of the country I’d yet visited. Interestingly, these made the dramatically different aspects of the local culture stand out even more to me, amplifying the feeling of surprise by standing out against a more familiar-seeming background.

For example, the cows. I saw more cows in my first afternoon in Mysuru than I’d seen in Mumbai or Bengaluru in a week. True, Mysore is somewhat less geographically dense (it would seem very dense by American standards, but felt practically suburban after Mumbai!) but these cows were still very much downtown, not in a rural area or a park or anything, just chilling on the pavement outside a restaurant or tied to a telephone pole. Most of them seemed in reasonably good physical shape (no open wounds or anything), and I noticed ear tags, so they appeared to clearly owned by people and not feral. Maybe it was common here to keep a dairy cow as a quasi-pet even in fairly urban neighborhoods?

Then there was the religious art. India is colorful in ways and places that are surprising to this Westerner; the temples were vivid cynosures of attention, brightly painted eyeball extravaganzas. Like three-dimensional comic books, they generally carried multiple statues of vividly rendered characters from mythological epics. I’m from New England, I’m subconsciously used to small local religious buildings being basically plain unadorned white with a pointy steeple on top. The riot of color and ornate detail in Indian architecture was a fascinating cultural experience8.

Even before visiting, I’d been fascinated with Mysore and its history, and visiting it in person did not disappoint. Learning about the city’s tradition of technological and industrial innovation and visiting its contemporary monuments, I was strongly reminded of one of my all-time favorite passages from the works of the controversial yet eloquently thought-provoking polymath Scott Alexander Siskind.

“Western medicine” is just medicine that works. It happens to be western because the West had a technological head start, and so discovered most of the medicine that works first. But there’s nothing culturally western about it; there’s nothing Christian or Greco-Roman about using penicillin to deal with a bacterial infection. Indeed, “western medicine” replaced the traditional medicine of Europe – Hippocrates’ four humors – before it started threatening the traditional medicines of China or India…

“Western culture” is no more related to the geographical west than western medicine. People who complain about western culture taking over their country always manage to bring up Coca-Cola. But in what sense is Coca-Cola culturally western? It’s an Ethiopian bean mixed with a Colombian leaf mixed with carbonated water and lots and lots of sugar. An American was the first person to discover that this combination tasted really good – our technological/economic head start ensured that. But in a world where America never existed, eventually some Japanese or Arabian chemist would have found that sugar-filled fizzy drinks were really tasty.”

-Scott Alexander Siskind on Slate Star Codex.

For me, reading about the history of the Kingdom of Mysore and visiting modern Mysuru underscored that concept of “non-Western modernities” that I’d been kicking around in my head for a while. Iron war rockets are just munitions that work: they were invented by a non-European culture, in our timeline! Zooming ahead to the modern age, open-source cost-free UPI is just a digital payment system that works, and it’s available in India but not in America yet. Building really ginormous solar farms on too-arid-to-grow-crops anymore farmland is just an energy system that works, and the biggest ones have been built in India and China.

After centuries where it has been very easy to conflate “modernity” and “the West,” we’re seeing a lot of absolutely fascinating new innovations arising from other parts of the world, with more voyagers than ever exploring the possibility-space of technologies that could be reified by human civilization. It’s going to be very interesting to see how the rest of this century develops!

Every noun related to the history of this part of India appears to have at least two (often more!) commonly accepted ways of being spelled in English: Mysore/Mysuru, Seringapatam/Srirangapatna/Shrirangapattana, Kaveri/Cauvery, Wodeyar/Wodeyer/Wadiyar, Haider/Hyder, Tipu/Tippu/Tippoo, and so on and so forth. It looks like we just have to accept that, because it doesn’t look to me as if there’s any prospect of a definite consensus being reached anytime soon: when I visited the Mysore Palace complex, I saw one sign saying “Mysore” and one sign saying “Mysuru” on the same face of the same building.

It was in 1782, in the middle of the Second Anglo-Mysore War, that Hyder Ali died and Tipu Sultan became the ruler of Mysore.

To be clear, I’m definitely not *personally* claiming that Hyder Ali or Tipu Sultan were great and heroic; they were conquering autocrats who tortured prisoners and committed brutal atrocities against civilians, like many premodern leaders. But it’s interesting that soldiers in the Continental Army of George Washington *did* explicitly claim they were great and heroic. Also, Hyder and Tipu were Muslim while the Wodeyars were Hindu, which means their legacy has become a “culture war”-type issue in modern India. I ran into a book in a modern Mysuru cafe that vociferously claimed that Tipu was fiercely committed to forcibly imposing Islam on his subjects and persecuting other faiths. I’m no expert on the period, and while there’s likely a good deal of truth to that claim, the fact that there’s a large Hindu temple in the middle of his fortified capital that survived his reign intact seems to me to indicate it’s not exactly a clear-cut situation.

Part of a long history of such adversarial innovation, arguably also including Rome reverse-engineering Carthaginian warships, America reverse-engineering Nazi V-2 rockets, the Soviets developing nuclear weapons with the help of Klaus Fuchs spying on the Manhattan Project, and China’s ongoing mass theft of American companies’ technologies.

Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV almost seems like the protagonist of a poorly written 1980s fantasy fiction novel, a literal reigning prince with an insanely improbable-sounding “successful at everything and loved by everyone” record. But that does appear to be the case! Many of the contemporary Indian princely state maharajahs of the period had internationally infamous reputations as spoiled playboys, so these plaudits weren’t just automatically raining in based on rank. It would be difficult to claim that a dam and a legislative council and an industrial base and an aeronautics company were all the result of really good propaganda.

The monuments of Srirangapatna are currently an official candidate for UNESCO World Heritage Site status.

Based on zero evidence and personal amateur-reading-history speculation only, so take it with not so much a grain as a full shaker of salt, but…I wonder if India hasn’t had its cultural spirit crushed by horrors in the same way that Europe, China, and to a lesser extent the U.S. have. There’s a whole literature on the European “renunciation of beauty” after the French Revolution, the centuries of shift from colorful baroque ormentation to minimalist modernism across domains ranging from art to architecture to fashion. That trend got super-charged by the twentieth-century modernist aesthetic sprung from the World Wars, giving rise to the Brutalist school of architecture, Le Corbusier, and a widespread feeling that invoking beauty in public works of art was a slippery slope to “national glory” and the well-trodden road to bloody atrocity. The eventual results have been dramatic: national leaders and super-rich merchants in 1700s Europe wore dramatic periwigs and silk-stockings and gold-embroidered waistcoats, national leaders and super-rich merchants in late-1900s and 2000s Europe wear plain black suits, or perhaps an unobtrusive blue.

Maybe China has in part imitated globally “fashionable” Western styles and in part suffered from its very own “spirit-crushing” events, such as the lengthy civil war and war with Japan segueing into the uniformly suit-clad Maoist regime’s famine-inducing “Great Leap Forward” and actively anti-art mass-iconoclastic Cultural Revolution. It’s possible that India will be the first really big country to fully industrialize in a period *without* a strong cultural legacy of “bright colors and fancy detailing is bad/old-fashioned/gauche.” With LEDs, holograms, drones, and robot-aided stonecarving in the mix, we might see some really psychedelic buildings arising in India in the coming decades!

Sam, don't worry about the spelling. There was no such thing as standardized spelling until the 19th century. This was primarily because they only started writing dictionaries in the mid to late 18th century. That was when the idea arose that there was one right way to spell a word. Even though I personally struggled with spelling when I was young, I think standardized spelling enables faster reading, so I am in favor of it generally. Maybe this is another way in which the spirit of India has not been crushed by Western conformity.

“It's a poor mind that can find only one way to spell a word.”

Quote attributed to Andrew Jackson

As a person who has the good fortune to claim Mysuru as my birthplace, and as the hometown of my mother and her family, I can say this is not a issue with spelling as much as it is a deep and divisive example of colonialism and its destructive, although perfectly understandable, effect on the locals who who spoke in dulcet Kannada. Little did they know that when they mispronounced their own names to keep up with the cantankerous demands of the British wielding their mightiest weapon, the English language with its innocent incapacity to pronounce anything right in India. For the record, Mysore was always Mysuru as we all

knew in our Mysuru hearts; Wodeyar by any other name never quite captured the Kannada sound of royalty, Tipu by all his names should by rights mean grand rocketry, even if not beloved by his Hindu citizenry. E.M. Forster once said about Indians imitating the British by ceaselessly and triumphantly uttering foolishly deployed idioms (to paraphrase) that there was once a dignified people in India before the English language arrived.

Dwarakanath Rao