The Nigerien Miracle...that was

For a brief time, this small, impoverished Saharan country in the middle of a jihadi-ridden war zone was a model of democracy and environmental action

UPDATE: on July 26th, 2023, a military coup appeared to occur in Niger, overthrowing the democratically elected President Mohamed Bazoum, who as of July 27 was reportedly a prisoner. As The Economist wrote: “The last seemingly solid government aligned with the West in the jihadist-plagued Sahel…seems to have fallen.”

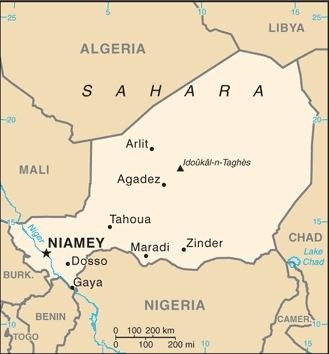

The west-central African republic of Niger1 is home to about 27 million people, and is one of the poorest and least developed nations in the world. In many ways, Niger seems to epitomize Western stereotypes of a “backward” country.

Niger was ranked 189th out of 191 countries in the 2022 UN Human Development Index report, with an HDI score2 of 0.4 out of 1.

Niger is categorized by the United Nations as a Least Developed Country.

Most people in Niger are subsistence farmers, with 72% of the labor force employed in agriculture as of 2019.

Niger technically banned slavery in 1960, but only criminalized slavery in 2003, before which traditional caste and religion-based forms of slavery continued with impunity.

The CIA estimates that its average GDP per capita (adjusted for purchasing power parity) is $1,200 per person per year, and the World Bank reports that 50.6% of the population live on less than $2.15 a day.

The fertility rate in 2022 was 6.6 children per woman, the highest in the world.

Polygamy is common, with 29% of Nigeriens living in households with a husband and more than one wife.

Subnational royals with titles like the Djermakoy of Dosso and the Sultan of Zinder are still influential figures in Nigerien politics.

And Niger’s in a really, really bad neighborhood, maybe the worst in the world, surrounded by jihadism, civil war, dictators, and military coup d'états.

On Niger’s southeastern border, the schoolgirl-abducting and flat-Earth-believing Boko Haram militants rage across Nigeria, Chad, and Cameroon.

To the east, Chad’s autocratic President Idriss Déby recently died in battle against northern rebels, and his son has non-constitutionally succeeded him.

To the northeast, Libya remains divided between a UN-recognized government and the forces of the warlord General Haftar.

To the north, Algeria remains a run-of-the-mill autocracy.

To the west, Mali and Burkina Faso have both recently lost their democracies in coups to newly minted military dictatorships, both of which are now working with Russia’s notoriously brutal Wagner Group mercenaries.

And across the Sahara and the Sahel, radical Islamic terrorists are on the march, with local offshoots of both al-Qaeda and Islamic State posing a major threat.

Niger has everything against it. It’s one of the poorest countries in the world, and it’s surrounded by seething turmoil. By any reasonable expectation, it should be a complete mess.

So how the heck is Niger a flourishing democracy that’s just pulled off one of the most impressive environmental restoration programs of the century?

Niger’s democracy is a small miracle

Make no mistake: Niger is still one of the poorest countries in the world, perched on the ragged edge of the Sahara and the Sahel, and plagued with jihadism. But it’s managed to do so much better than its neighbors. For one thing, Nigerien President Mahamadou Issoufou gracefully left office and ceded power in 2021 when his second five-year term was up. He was the ninth President of Niger, and the first ever to actually obey term limits. This is rare among African leaders in general: by simply obeying his country’s constitution, President Issoufou won the Ibrahim Prize, an international $5 million fund set up to reward African leaders who step down when their terms expire instead of illegally clinging to power. The Ibrahim Prize is meant to be yearly, but has only been awarded seven times since it was established in 2007, because most years no African leader qualified.

This set up the country’s first-ever democratic transition of power (Issoufou was elected democratically after a military junta was disbanded) in Niger’s two-round 2020-2021 presidential elections. It seemed like a recipe for discord, with multiple former presidents and prime ministers participating (even including several former military coup leaders!) and yet it peacefully produced a democratically elected new leader. President Mohamed Bazoum, a man from the Diffa Arab minority, has a history of opposing coup-imposed governments and campaigned on education and equality for women and girls. He won the election and took office with only small-scale protests by another candidates’ supporters, and no serious struggle. That’s more of a peaceful transition of power than the United States managed in 2021!

And President Bazoum, now in his third calendar year in office, seems to be doing pretty well.

He’s working closely with America and France to fight jihadists spiling over from al-Qaeda and Islamic State in Mali and Boko Haram in Nigeria. As many coup-imposed West African governments lean towards Russia, the Financial Times recently described him as “the west’s staunchest ally in the region.”

His government recently contracted with a British energy company for 200 megawatts of solar projects and a 250 megawatt wind farm, both of which should be completed by 2025 and will substantially increase the amount of electricity generated in the country. (Only 19.3% of Nigeriens had access to electricity in 2020).

And he’s trying to build boarding schools for teenage girls (many currently drop out and get married at 13), and urging his ministers to set an example by not taking a second wife.

There’s very little commentary on the Nigerien government in English-language media (though there’s a decent amount in in French-language media), but this is a fairly impressive record for one of the poorest countries in the world.

Niger’s small farmers are building a good Anthropocene

Furthermore, in the past few decades, Niger’s subsistence farmers have accomplished something remarkable, choosing en masse to re-embrace the practice of agroforestry, growing crops under the shade and shelter of trees.

Since the 1980s, the people of Niger have increased their nation's forest cover by over 200 million trees, covering at least 12 million acres-an area larger than Massachusetts and Connecticut combined. (For context, Niger itself is slightly larger than Texas and California combined). This is amazing both because of the scale of the accomplishment and the extraordinary context in which it occurred. Despite Niger’s extreme poverty, this incredible reforestation was entirely a grassroots campaign conceived of and executed by ordinary Nigerien citizens, not a planned international aid program or a government-led initiative. Indeed, Western scientists only realized it was happening in 2004!

The Nigerien government had actually tried a reforestation program in the 1970s, but it failed, with fewer than 20% of the 60 million trees planted surviving. The modern movement was likely sparked in 1983 by a group of farmers who'd traveled to look for work, and didn't return in time to clear their fields of young trees before the rainy season. When they planted around them, they noticed that the crops grew better, fertilized by falling leaves, shielded from sand and sun by the canopy overhead, and moistened by evapotranspiration. This result spread by word of mouth to other local farmers, and was popularized further by Australian missionaries and American Peace Corps volunteers. Notably, the method didn't require planting any trees, which would have meant seedling nurseries and seed collection infrastructure, but simply encouraged farmers to let alone the naturally-regrowing trees amidst their fields.

One key tree species used was Faidherbia albida (pictured above, with maize growing underneath). Its life cycle is the opposite of the other local plants, as it goes dormant during the rainy season (not competing with young crops) and goes into leaf in the dry season, casting critical shade when it’s most needed.

The agroforestry movement spread across the country like wildfire. Ecologists studying the phenomenon state that "200 million trees" and "12 million acres" are very low-end, conservative estimates, based on aerial imagery analysis since there's no central project database tracking progress.

On the ground, the areas around the cities of Zinder and Maradi have been transformed. It's estimated that the newly tree-rich areas of southern Niger have produced an extra half million tons of grain per year, enough to feed 2.5 million people, and kept up a surplus even during the drought of 2011. “Before, farmers often had to sow their crops two, three times after they were destroyed by strong winds that covered the crops with sand,” said Aichatou Amadou, a Nigerien farmer from Droum in the Zinder region, to National Geographic. “[Since planting trees] I only have to sow my crop once.” Now, aid groups are sending farmers from other countries to Niger to learn about this ultra-low-cost regeneration method, and similar stories of farmer-led agroforestry movements and popping up in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Malawi.

The modern history of Niger is a truly inspiring saga. Nigeriens are fighting for democracy, standing strong as a bastion of freedom in a landscape of jihadism and Russian-backed military dictatorships. They’re working to educate girls and build solar and wind power to kickstart a climb out of poverty. And farmers are protecting their livelihoods from climate change-supercharged desertification by sharing the wisdom of agroforestry, adapting to a warming world by the sweat of their brow. Some of the most adversity-stricken people on Earth using their wit and their will to create a better life, and a better world.

If Niger fell to jihadis or the Wagner Group, it wouldn’t be “just another coup”: one of the brightest lights of Africa and one of the most inspiring examples of the human capacity to overcome adversity in the world would be stifled. It’s good that the West is supporting Niger militarily, that Western companies are starting to build out clean energy for the country, and that Western scientists and aid workers are starting to recognize and share the lessons of Niger’s extraordinary agroforestry success. If any impoverished country deserves particular recognition and support from the wider world, Niger does. I’m proud to share a world with Niger and its people.

Just north of the much larger and better known Nigeria; both are named after the majestic and deeply geographically weird Niger River

For context, the USA had an HDI of 0.921, Mexico had 0.758, and India had 0.633.

Wow, I like to think I'm well-informed, since I follow the BBC world service and they do have quite a bit of African coverage. But I missed this about Niger. Good to read.