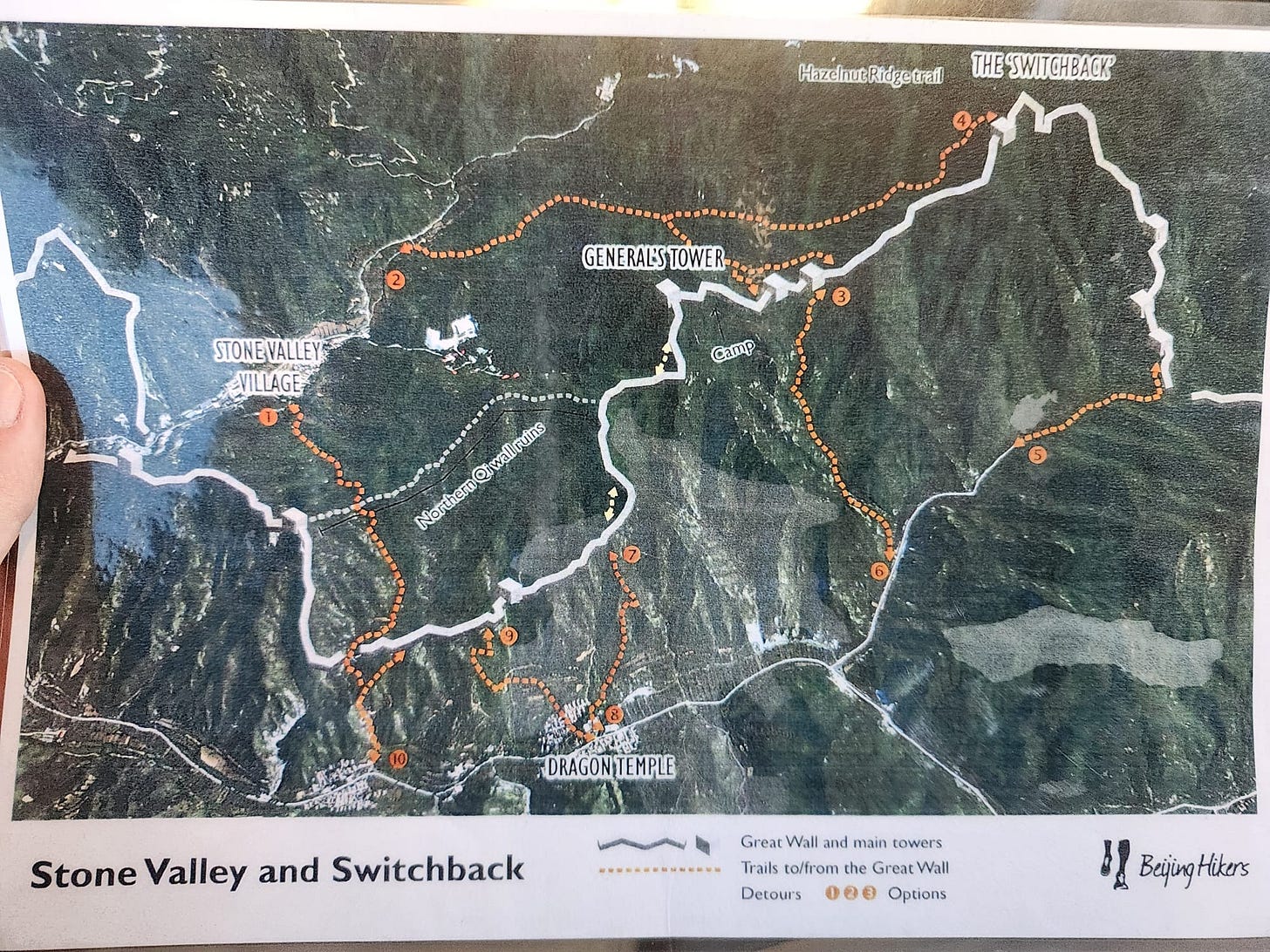

In the early morning of my second day in China, I woke up to rendezvous with the amazing Beijing Hikers group for a guided hike1 along the Chenjiapu “wild wall” section of the famed Great Wall of China. We were a hiking party of four: myself, a nice backpacker couple from Australia, and our Beijing Hikers guide Mr. Huang Wei.

After two hours on the road from Beijing, our driver Mr. Ya dropped us off at the starting point of the hike, just over the border in Hebei Province. We wrapped up in five layers of winter gear, peeled crampons over our shoes, and began to climb up to the Wall itself.

We started the climb from a valley home to several abandoned half-built apartment buildings2, and quickly reached the Wall itself. We could walk right along the top of it, amid fallen stones and sprouting grasses and shrubs. Wind-dwarfed trees, of the morphology called “krummholz” in the Alps, rose from between the cracks in the monument and crowded along the edge of the battlements.

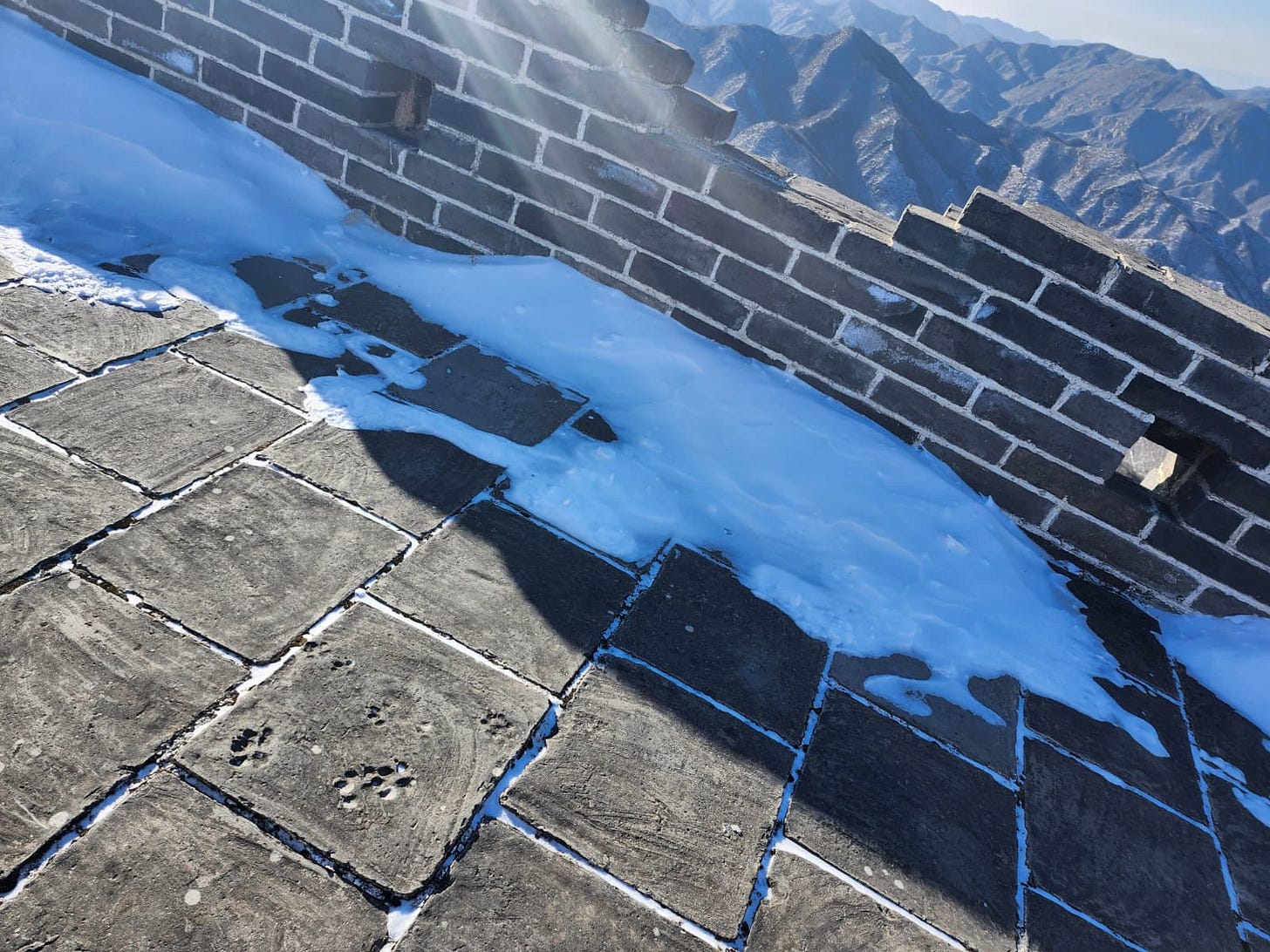

It was bitterly, bitterly cold. Minus eleven degrees centigrade, but it felt more like minus twenty due to the massive windchill — we were, after all, literally on top of a wall built to run along the top of hills, as exposed as you could get. A thin layer of snow and ice, rising to shin-height in shaded stairwells, made our footing treacherous, as did the unrestored patches with shifting rocks and disintegrating slopes. Taken in conjunction with my backpack holding my entire trip inventory as I’d checked out of the hotel that morning, it added up to the most strenuous outdoor adventure I’d done in months! I was loving every moment of it. (Here’s my video!)

Our guide told us that the effects of climate change were already visible in these conditions nonetheless; in January two decades ago, this section of the wall would have been minus twenty easily and mantled in knee-high snow.

As we ascended further, a magnificent landscape spread out before us. The big lake on the left from our perspective was the Guanting Reservoir, a major supplier of drinking water to Beijing that was completed in 1954. The Guanting wind turbines on the shore of the reservoir were the world’s largest-ever wind farm when the 200 MW first phase was built way back in 2004. They’ve since been positively dwarfed by the breakneck progress made by two-and-a-bit exuberant decades of a China-led global renewables revolution: the largest wind farm today is the Jiuquan Wind Power Base in Gansu, with over 10 GW (10,000 MW) already built and plans to scale up to 20 GW. But they’ll always be a pioneer3, early heralds of a glorious new age of clean electricity-powered civilization.

Mr. Huang also pointed out a distant snowy patch on a mountain that had been a ski facility for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics. I noticed an unusual cluster of similar tall buildings near the Guanting shore, and asked what it was. Our guard told me that it was modern Tumubao, and shared its fascinating history.

In 1449, the arrogant and inexperienced 21-year-old Emperor Zhengtong (aka Yingzong, sixth ruler of the Ming Dynasty, great-grandson of Beijing founder Yongle) unilaterally decided to override his generals and personally lead the Beijing army garrison on a highly risky spontaneous sortie against the Oirat Mongols invading from the north. The Oirat Mongols quickly surrounded and defeated the hastily prepared, poorly supplied, and incompetently led army and captured the young emperor at the “Crisis of the Tumu Fortress,” though the generals rallied to successfully defend Beijing itself. This humiliating disaster drove generations of future Ming emperors to invest massively in upgrading and manning the Great Wall of China. By the 1500s, they were paying for much of it— as Mr. Huang pointed out with impressive of global context — with silver mined by Spanish Empire slaves in the New World mountain of Potosi, connected to Eurasian economies by Pizarro’s invasion of Peru in the 1530s and early modern Europe’s recurring trade deficit with China as they used precious metals to buy fine porcelain (the classic “Ming vase”) that couldn’t yet be made locally.

As we continued to walk along the Wall, we learned more and more about it. The guard towers, including the famous “General’s Tower,” were practically wind tunnels, concentrating the freezing gusts to make us feel even colder on than the rest of the wall. Mr. Huang told us that Ming Dynasty soldiers on the Wall were sometimes paid in firewood. The immense manpower requirements involved in making millions of bricks and schlepping them up to the top of the hills and ridgelines from the Bohai Sea to the Gobi Desert can only be imagined today. Along the upgraded Ming-era Wall, simple messages could be transmissed for miles in just minutes, making the whole thing an optical telegraph — a classic “The beacons are lit! Gondor calls for aid!” situation.

As I chatted more with Huang Wei, I learned that our guide, besides being very knowledgeable about the Wall and surrounding landscapes, was an absolute mensch.

His other passion was disability rights, and he was a trained Chinese sign language interpreter. One of only about 100 sign language interpreters in the entire 33-million-person Beijing metro area, and one of only five who could also speak English. He told me about an excursion he’d organized for disabled folks to see the Great Wall, during which the deaf people had helped carry the wheelchair-bound over steps! Due to his English skills, he’d also appeared in a U.S. Embassy event on the Great Wall escorting disability rights advocates led by legendary blind triathlete Michigan Supreme Court Justice Richard Bernstein. Mr. Huang urged me to use my newsletter to tell disabled people and groups in the United States that if they visited Beijing, the Beijing Hikers group had accommodations to help them experience the Great Wall. I now do so.

On one of the steeper and rougher descents, we spotted animal tracks.

Eventually, we came to a transition point where a modern restoration project just a few years ago had resheathed an entire section of the Wall in newly-made bricks, replacing the disintegrating rock and proto-soil with a new pattern of sharp-cut stone. I was pretty surprised: it was like seeing a new addition to the Pyramids or the Parthenon. One of the modern tiles made for the restoration even had cat prints in it!

I think China just fundamentally does not frame tradition and modernity as opposed to each other like so much of the West does. There’s no NIMBY-style sense that a historic site is “contaminated” by building something new. Traditional and futuristic go together like chocolate and peanut butter, even amplifying each other. “Yes, more of both please, let’s do the tradition bigger and better and more impressively using modern technology!” Maybe it comes of having so many previous cycles of what seemed like modernity at the time, multiple centuries-long dynasties rising and falling and building on the remnants of the past. A matryoshka civilization. After all, even the pre-modern-restoration bits of the Wall we were stepping on were a result of the Ming building in stone right on top of the Qin4 rammed-earth ramparts.

We also saw several signs during the day warning against kindling fires in the woods, with a very Chinese anime tiger mascot seemingly emulating the classic “Smokey Bear” U.S. Forest Service campaign against forest fires. Ken Burns called national parks “America’s best idea,” and in recent years China been rapidly rolling out new protected areas and a formal National Park system explicitly modeled on the American example. That’s a legacy my home country can be extremely proud of.

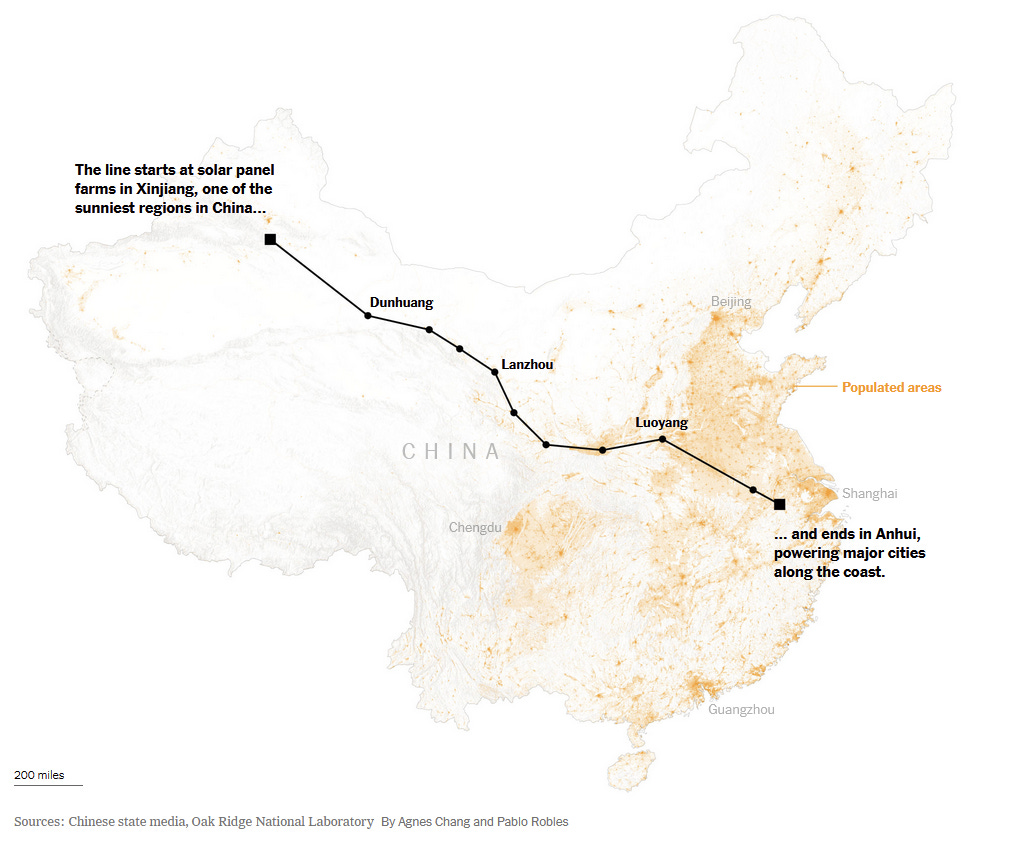

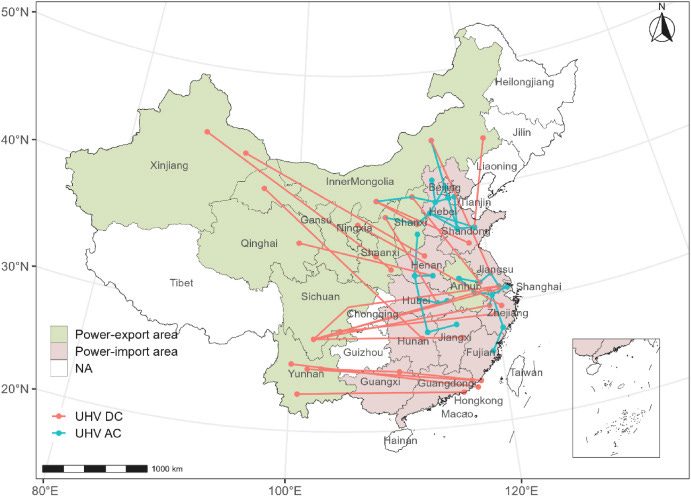

As we neared the end of the hike, we saw power lines arcing across the hills, occasionally crossing over the Great Wall itself. China has built a world-class ultra-high-voltage (UHV) “supergrid” in recent years, reportedly building over 80 times more new power lines than the United States in the second half of the 2010s. From 2020 through 2025, China’s total UHV network length reportedly increased from 17,400 miles to over 24,854 miles. And it’s still growing very fast.

The New York Times recently reported that China’s longest-yet high voltage power line, one of dozens, brings clean electrons from a solar farm in Xinjiang to cities in Anhui — a transmission over a distance similar to that from Idaho to New York City! One big innovation has been the use of direct current, which has much lower losses over long transmission distances but will then need to be converted into alternating current to run most devices, from EVs to high-speed trains to smartphones.

It occurred to me that just as the Great Wall in its various historical iterations, from Qin Dynasty rammed-earth ramparts in the 220s BCE to Ming Dynasty stone towers in the 1400s CE, was meant to defend China from the existential threat of invaders from the Eurasian steppe, the gigantic new “renewables bases” in modern China’s vast hinterland of steppes and deserts are a similar modern echo as landscape-scale “defenses” against the existential threat of climate disruption. Both are world-historic big construction efforts out on the fringes of traditional China, building something in low-population-density landscapes to protect — or electrify — the teeming cities of the core. China’s fast-spreading supergrid is a Great Wall for the Anthropocene.

Right on the edge of the ridge we could see before we turned off the wall, we spotted a little shed that our guide told us was a solar-powered automated landscape-scanning wildfire watch early warning station. We could even see the outline of the cameras. I’d previously written about a similar such effort in Arizona, a climate adaptation sector of the global “Naturenet” trend of providing live 24/7 data feeds on ecosystems.

As the sun began to set, we eventually turned off the Wall and stepped through fresh unbroken snow amid bare trees along a buried trail, sloping down towards a village where our driver would pick us up. It reminded me of my childhood winters in the woods of New England. My Australian hiking buddies were unused to the snow, both enthused by the experience and surprised at the extensive potential for falling over.

The trail in the woods eventually met a more stable gravel path, which Mr. Huang told me had been trodden by invaders of Beijing from Li Zicheng’s peasant rebels in 1644 to the Imperial Japanese in 1937. Eventually we came to the village itself, with a trailhead and visitor center near what looked like an elementary school playground. And so the hike came to a close.

It cost only about $62 in U.S. dollars, including transport from Beijing. As it turned out, an incredible bargain! China intentionally manipulates its currency, intervening with state funds in “buying dollars” exchange trading to keep the value of the renminbi (aka yuan) low enough to provide its many exports with an extra competitive boost on the international stage. A side effect is that prices in China for very high-end goods and services are incredibly cheap when you’re arriving with a dollars-and-euros mindset!

Part of China’s ongoing real estate property bubble, where decades of urbanization had driven many small-scale investors to think that building new homes was a surefire ticket to an asset that would always rise in value. However, China’s population peaked in 2023 and has been declining every year since then, as the global demographic transition manifests unusually rapidly and steeply in a society still reeling from the late 20th century’s one-child policy. Lots of mom-and-pop would-be landlords lost their pension money, and there have been some major bankruptcies and economic ripple effects. There are now far more available housing units than people to fill them in modern China, and a financial crunch for many companies as a result — an ironic “Scylla and Charybdis” opposite pole to the situation in many other developed countries.

As described in this highly perceptive 2009 article — way ahead of its time!

Qin and Qing are not the same dynasty at all — in fact, they’re often called the first and last dynasties to rule over a unified China. The Qin dynasty ruled in the 220s BCE, the Qing dynasty ruled over 1,500 years later from 1644 to 1911. I once caused substantial controversy in a family Scrabble game by playing “Qin” one turn and then adding one letter to play “Qing” the next.

Wonderful to read your China chronicles! I visited the Great Wall in December ~15 years ago. It was indeed freezing cold, but such an incredible spectacle. I greatly appreciate your Anthropocene perspective and photos as you travel around.

Really enjoying the travelogue! Keep having fun and sharing it.