Repost: Review of The Rescue Effect by Michael Mehta Webster

A lovely read chronicling the ways in which wildlife populations can rebound

Michael Mehta Webster is a Ph.D. zoologist, Environmental Studies Professor at NYU, and former Executive Director of the Coral Reef Alliance. His new book. The Rescue Effect provides a whirlwind tour of the global fight to preserve Earth’s biodiversity, focusing on the “rescue effect,” Dr. Webster’s umbrella term for the multitude of ways wild creatures can restore their populations. Dr. Webster describes six main facets to the rescue effect: demographic rescue, reproductive rescue, genetic rescue, phenotypic rescue, geographic rescue, and evolutionary rescue.

This review was first published in December 2022, and is now republished for a wider audience.

Demographic rescue is very simple: animals moving into another part of their range where that animal’s population is low. New immigrants coming in, in other words. This can be natural diffusion, or human-aided, as in the case of wolves in Yellowstone or dozens of other reintroduction projects.

Reproductive rescue is when animal populations boom to fill unoccupied habitat, often occurring once a particular stressor like poaching or pollution is removed. In The Rescue Effect, Dr. Webster discusses the case of India’s Panna Tiger Reserve. Its entire tiger population was eliminated by poachers in 2009, but after the corrupt local officials were replaced and six new tigers were gradually introduced (an example of human-mediated demographic rescue!), reproductive rescue brought the population back up to over sixty tigers by 2020.

Genetic rescue simply describes the diversity and beneficial adaptations that new genes from elsewhere bring to a population. The Rescue Effect describes how sockeye salmon have a really interesting twist on this: most salmon instinctively return to spawn in the same river they were born in, but about 1% “stray” and end up in a new river system1. This prevents inbreeding and allows beneficial genes to spread throughout the species. The American Chestnut Foundation’s epic decades-long quest to use blight-resistant Asian chestnut genes to restore the fungus-ravaged American chestnut also counts as a human-mediated example of genetic rescue, as do several ongoing efforts to breed or engineer heat-resistant “super corals.”

Phenotypic rescue is when organisms make changes to some part of their phenotype (all of their observable characteristics, so their body plus all of their behaviors) to survive better in the face of new threats. For example, corals in Honduras’ Roatan Reef appear to be “learning” from prior instances of coral bleaching, taking in different strains of symbiotic algae that can survive warmer waters. As Dr. Webster writes, it’s “like an elite sports team trading for new players to fine-tune performance.” Humans can help make phenotypic rescue possible by reducing the number of stressors that wildlife have to adapt to at once: for example, corals are more likely to survive bleaching in areas where water quality has improved due to anti-pollution efforts.

Geographic rescue is when species move to new areas outside their historic habitat, with or without human help. This is becoming really common in the age of climate change as species’ preferred temperature ranges all shift at once: for example, the Audubon Society has a great interactive database called “Survival by Degrees” showing the likely climate-driven range shifts of 389 North American bird species under different warming scenarios. A chapter in The Rescue Effect profiles the case of the mountain pygmy possum, an adorable little marsupial native to the mountain peaks of the Australian Alps. Mountain pygmy possums are rapidly losing their alpine home to climate change, and don’t have anywhere higher to go (a common problem for mountain species: they can’t just move north to follow cooler temperatures, they’re stuck on “islands of coldness” that are rapidly shrinking). Conservationists are now gradually introducing a population of pygmy possums to cool lowland forests, which are too far away for them to access naturally but are similar to the forests where their recent ancestors once lived.

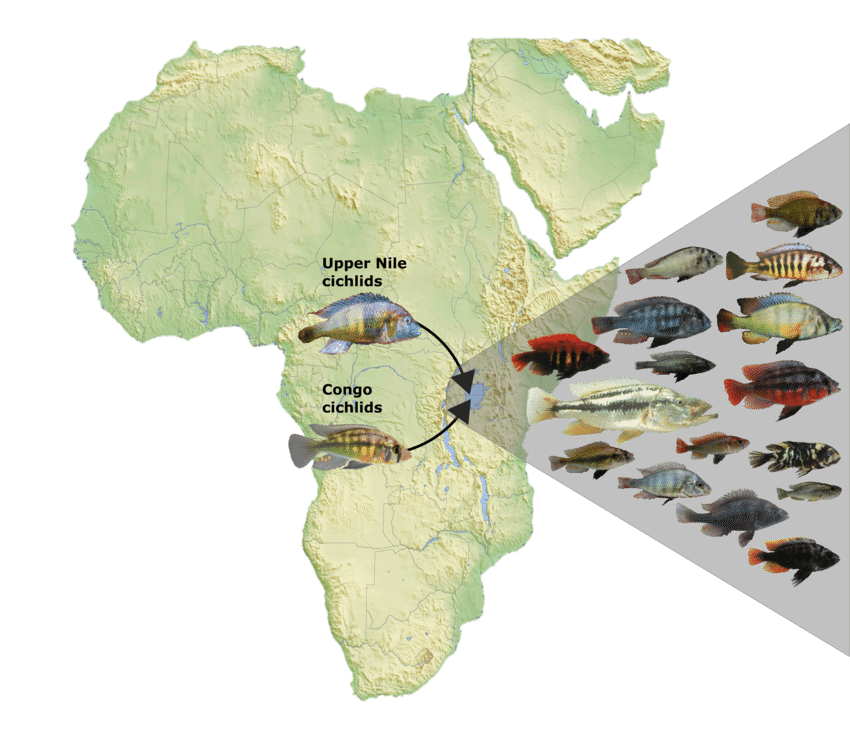

Evolutionary rescue occurs when species evolve new traits to survive in the new conditions of the Anthropocene. For example, Lake Victoria used to be home to hundreds of closely species of haplochromine cichlids (forming a “species flock”), descendants of ancient hybridization between Upper Nile and Congo cichlids. Many of these species went extinct in the late 20th century (we still don’t know exactly how many) when pollution spiked and the voracious Nile perch was introduced to the lake. However, many of the surviving haplochromine cichlids have managed to rapidly evolve to survive in a murkier, perch-filled lake. As described in The Rescue Effect, the “orangehead” cichlid (Haplochromis pyrrhocephalus) had lost 99.99% of its population by 1987, but has since bounced back immensely, with populations 18,000 times more abundant than their 1987 low point. The orangeheads have experienced phenotypic and evolutionary rescue, moving into shallower waters, eating different foods, and evolving a more streamlined body shape that may have helped them outswim Nile perch. Hybridizing with another species of cichlid may have enabled such rapid evolution. Across Lake Victoria, similar stories of rapid evolution, hybridization, and diversification appear to be launching a new species flock, capable of surviving the new stressors of the Anthropocene.

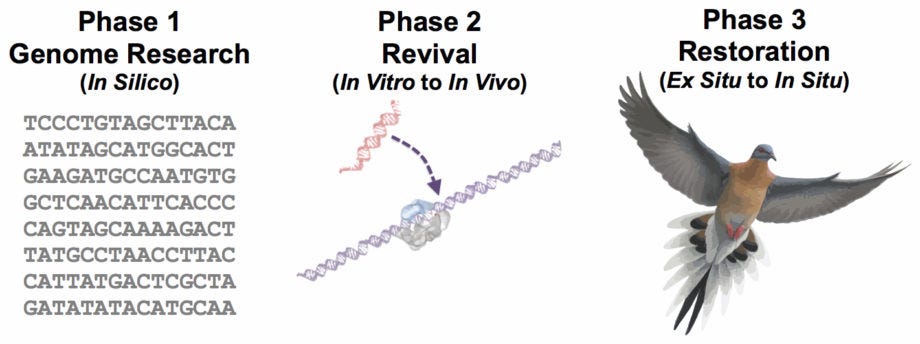

Finally, Dr. Webster identifies a potential seventh form of the rescue effect waiting in the wings: resurrective rescue. There are currently active research teams working to genetically resurrect woolly mammoths, passenger pigeons, and Tasmanian tigers. (This “de-extinction” movement is a longtime passion for this writer, who has previously interviewed Ben Novak, the paleogeneticist working to bring back the passenger pigeon, and completed a pro-bono GIS project mapping historical passenger pigeon records).

The Rescue Effect is very much in favor of the kind of cutting-edge, innovative, proactive conservation that this newsletter tries to profile. In a rapidly changing world, trying to keep ecosystems preserved in amber, a static image of the past, is a fool’s errand. Dr. Webster powerfully makes the case that we need to enable and support the changes brought by the rescue effect, from species moving to new habitats to prioritizing new behaviors to evolving new traits.

“By managing to promote the rescue effect, the goal shifts from trying to prevent change to guiding change in directions that people value. This is an emerging paradigm in conservation, and it’s less like managing an ancient art museum and more like parenting.”

-Dr. Michael Mehta Webster, The Rescue Effect

This writer wasn’t immediately sold on this book’s fundamental narrative conceit; it’s not obviously intuitive to group all of these varied, multicausal processes under the name of “the rescue effect,” which seems to imply a single, unified thing. But as the different forms of the rescue effect are elaborated on over the course of the book, it really works; Dr. Webster uses a single term to draw attention to the collective power of the multitude of ways the natural world is stronger than we think, adapting to change and evolving new species, communities, and ecosystems. All the species profiled in The Rescue Effect are using more than one of Dr. Webster’s “types of rescue,” a good argument for his decision to treat them as multiple facets of the same process. And humans almost always have a chance-and a choice-to strengthen the rescue effect, and help our wild kindred find new ways to live on the Earth of the Anthropocene.

“Because of the rescue effect and our ability to strengthen it, we have good reason to believe that the future of life on Earth will be bright.”

-Dr. Michael Mehta Webster, The Rescue Effect

The Rescue Effect would make an excellent holiday gift for anyone interested in wildlife conservation, climate change, or the future of Earth’s biodiversity. It’s engaging, fast-paced, well-researched, and profoundly hopeful. It makes you excited for the future of this planet’s ecosystems and wild creatures. Read it!

There are so many more amazing stories I want to write about—please consider a paid subscription to The Weekly Anthropocene!

Lately, the far-flung movement of these strays has been allowing sockeye salmon to colonize new rivers farther north in the warming Arctic as well, an example of geographic rescue.