Repost: The Weekly Anthropocene Interviews Amaroq Weiss, Senior Wolf Advocate

A wide-ranging conversation on the state of wolves in America, now republished

Amaroq Weiss is the Senior Wolf Advocate with the Center for Biological Diversity, leading wolf conservation efforts on the West Coast and on the federal level.

A lightly edited transcript of an exclusive interview with her follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Ms. Weiss’ responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

This interview was first published in February 2023, and is now republished for a wider audience. It’s particularly notable that since the first publication, there have been further credible sightings of a wolf (and/or coywolf, see below) in Maine, this writer’s home state!

Can you discuss your personal story and what led you to become Senior Wolf Advocate with the Center for Biological Diversity?

I grew up in the Midwest, in Iowa, which is a place that historically had vast prairies covered with wolves, bison, and elk, and all kinds of species we managed to wipe out. I was really cognizant of that. I grew up in a small university town, I had a lot of people instructing me on what the natural history was around that area.

I’ve always been drawn to canids. If my parents couldn’t find me at dinnertime, I was with whatever neighbor had a dog. There were probably two books were instrumental in leading me to what I do. My background is as a biologist and a lawyer, I have both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in entomology. I gravitate towards species and issues that are underdogs; most people hate insects, I think they’re magnificent and I’ve always thought they needed championing.

Me too!

You too?

Yeah, I love insects.

Yeah, they’re just remarkable, and we continue to learn more and more about them.

I later went to law school and ended up becoming a criminal defense attorney, defending indigent defendants. I was court appointed, a federal defender, appellate attorney.

In high school, I was really fascinated by wolves. I began to get a much more nuanced understanding: the Endangered Species Act was passed in 1973, wolves were first listed for protection under it in 1974, so I began to follow things a little bit more then. In college, I read a book that I always recommend to everyone, Barry Lopez’s book Of Wolves and Men. It’s a fantastic starter book for anyone learning about wolves. Barry Lopez is a remarkably beautiful nature writer, with grace, but also a great researcher and compiler of different things that tell a great story. So his book Of Wolves and Men helped me understand the persecution of wolves in this country. I already got that they were magnificent animals, I didn’t understand the depth of the wolf hatred in this country.

Later on, practicing law, I read another book by Hank Fisher, called Wolf Wars. This was 20, 25 years later, and by this time wolves were being reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park. Wolf Wars talks about the enormous political battles it took. Twenty years of political battles to get wolves reintroduced to Yellowstone, even though they’d been listed under the Endangered Species Act for all that time. And then I began to put the pieces together. Nonnative peoples that colonized our country brought with them this wolf hatred, and to this day, the wolf is still this very beleaguered species. I thought, well, I’m a biologist, I’m a lawyer, I like to fight for underdogs, I’m fascinated by wolves. I think this is something I need to be involved in.

“I thought, well, I’m a biologist, I’m a lawyer, I like to fight for underdogs, I’m fascinated by wolves. I think this is something I need to be involved in.”

-Amaroq Weiss

I was in San Diego at the time working at the federal public defender’s office, and I learned about the California Wolf Center, which is in eastern San Diego County, in the Cuyamaca Mountains. And they’re part of the species conservation plan for restoring Mexican gray wolves. They’ve got Mexican gray wolves in captivity there [as part of a highly successful captive breeding program], they’ve got an ambassador wolf program. And I went out there and started volunteering with them. After that, I got a job with Defenders of Wildlife, became their Western Director of Species Conservation. Moved to Oregon, had the incredible experience of working with and supervising staff working in Alaska, Montana, and Idaho on wolves and grizzlies and black-footed ferrets. I was working on sea otters and other small carnivore species in California. And it was a swirling recognition that wolves aren’t the only thing that’s important: they’re super, super important, but what they’re emblematic of is how we don’t care for all of these other species that are not seen as that important, right down to those insects. Imagine trying to get the public interested in the American burying beetle, right? It’s not the same thing as a wolf.

So after I left Defenders, I then worked for the Mexican Wolf Conservation Fund, I did some contract work for other organizations, and I started working for the Center for Biological Diversity ten years ago this month. That gave me an opportunity to really focus on wolves in the West Coast. When I lived in Oregon, I’d been a stakeholder in the process to advise the agency on developing its state wolf plan. After moving back to California, I got to be a stakeholder advising the California agency on developing its state wolf plan. The experiences I have gotten to have in my career have so deepened my understanding of how we need to save these species. That these species are under attack from politics every single day. And also just the lack of understanding in the public of how important they are, and that we can live with them. My work is really focused on making sure that agencies are not killing wolves illegally, that they’re restoring wolves where they’re supposed to be restoring them, and helping to bring information to the public.

“These species are under attack from politics every single day. And also just the lack of understanding in the public of how important they are, and that we can live with them. My work is really focused on making sure that agencies are not killing wolves illegally, that they’re restoring wolves where they’re supposed to be restoring them, and helping to bring information to the public.”

-Amaroq Weiss

I get to connect with a lot of scientists in my work, and it’s really, really joyful.

Can you tell me about the recent growth of wolf populations in California? It started with OR-7 in the early 2010s, and then we started getting a couple packs…

That’s a really amazing story. In 2001, I and other conservation groups were testifying in Northern California, in Siskiyou County, which was trying to pass a resolution to prohibit wolves from coming into California. I said, you can pass any resolution you want, the wolves don’t read. They’re gonna be here. They’ll be here in 10 to 20 years. And just a little over 10 years later, OR-7 came into California. He was a wolf that was born in northeast Oregon, and his parents were also long-distance travelers, they both came from Idaho, they made it across the Snake River into Oregon, set up their pack, the Imnaha Pack, and OR-7 was in their first litter. And in 2011, he left his pack, crossed the state of Oregon diagonally down into southwestern Oregon. And in late December, actually on the anniversary of the passage of the Endangered Species Act, he lifted a paw on the Oregon side of the border, set it back down on the California side of the border, and kept on going.

He became our first wild wolf in California in 87 years. The last two known wolves in California had been killed in 1922 in southern California and 1924 in northern California. That tells you right there that we had wolves once widely distributed across the state, and there’s lots of historical evidence as well. And evidence from Native American practices, ceremonial dances, artwork, and stories in California. We know they once lived here. But OR-7 returned, basically, to a wolf-less state. He spent 15 months here, returned to Oregon, came back to California a couple more times. Because he had shown up in California, my organization and others filed an administrative petition with the state to gets wolves listed under California’s state endangered species act. A lot of people don’t know this, but I think it’s 48 out of the 50 states that have their own state endangered species act. That’s like the federal Endangered Species Act, but it’s often nowhere near as protective as the federal Act. California is distinct in that respect, it’s very protective, it’s the most protective state-level endangered species act across the country. We knew we needed to get wolves listed here because A, OR-7 was just going to be the first. We knew there would be more wolves coming from Oregon. And B, the federal government has, since early 2000, tried to strip wolves of federal protections. We knew if that happened again, any wolves coming to California were going to need the state protections. So we managed to get that done successfully, with the broad support of the public, amazing testimony at public hearings, presenting the science and the law. And we got it done just in time.

Because in 2015, California’s first known wolf pack, the Shasta pack, was confirmed. They also were originally related to the wolves that OR-7 came from, that Imnaha Pack in northeast Oregon. Unfortunately, about two months after they were confirmed, after they were implicated in some livestock conflicts, that entire 7 member Shasta pack disappeared. And many of us feel that they met a bad end, that they were potentially poisoned. You just don’t have an entire wolf pack like that disappear. They usually come back next year and use the same area to den. They never came back. One of their offspring was actually found in Nevada, about a year later. We know it was him because scat was collected at the place where that wolf was seen and DNA tested. But none of the rest of the pack ever showed up again.

So then we started to get new packs. In 2015, 2016, we started to see more wolf sightings. The very next wolf pack that was formed was called the Lassen Pack. The breeding male of that pack was actually a son of OR-7, because after OR-7 left California for good, he went back to southwestern Oregon and established his own pack there, the Rogue Pack. In 2014 he and his mate had their first litter of pups. One of those pups came to California a year or two later and formed the Lassen Pack. They’re still around. The Lassen Pack has a huge territory, about 500 square miles, and they range across Plumas and Lassen Counties. If you take a look at a map of Northeastern California, you’ll see where these animals live. The original female of the Lassen Pack, her genetics show she traveled all the way over from Wyoming. She traveled a long way to meet up with a wolf in California.

Besides the Lassen Pack, we have two other confirmed packs in California now. The Whaleback Pack lives in eastern Siskiyou County, which is just to the north of Lassen County. And the female of that pack is also related to OR-7.

The Beckwourth Pack is in southeast Plumas County. There were originally three adult wolves seen in that pack seen in 2021. No evidence of having pups that year. They believe the pack may have had at least one pup in 2022. And at least two of those wolves are offspring of the Lassen Pack. That’s a good sign that wolves born in California are now going off and forming their own packs.

Besides all of these swirling wolf developments, we have a few other wolves that have really caught the attention of the media. One was wolf OR-54, another one of OR-7’s daughters, born in 2016. She came into California, traveled in California for about two years, went back to Oregon a couple times. She traveled over about 8,700 miles before she was found dead. We don’t know the cause of her death yet, it’s still under investigation, so we assume she was illegally killed.

And then OR-93. That’s a wolf that was born just southeast of Mount Hood, in Oregon, in the White River Pack. He came to California right around January-February 2021. He traveled all the way down to Yosemite, then cut across the Central Valley and ended up on the coast of California! Over in the Los Padres National Forest area, in the Ventana Wilderness, Chumash Wilderness area. He is therefore the first confirmed wolf in those counties in 200 to 300 years. So we were really rooting for him. In order to make that trip he had to cross three of California’s busiest highways, Highway 99, Interstate 5, and Highway 101. And unfortunately, as he was turning around and heading back, he was hit by a vehicle and killed.

He was another wolf in California that really reached media attention globally. I got a call at 6 o’clock in the morning from the Guardian in London wanting a story about OR-93. So all of these wolves that come into California, what they’ve done is they’ve written a book like Barry Lopez did, just by being here. They have shown the world what wolves do. That they travel long distances, both males and females, and they do it to find mates and establish territory of their own. And if they find good wolf habitat, they can prosper. And what they need is human tolerance. More than tolerance in my view, we need to embrace these animals, but tolerance is the low bar. Because without that tolerance, you end up with things like the Shasta Pack entirely disappearing, or OR-54 being illegally killed.

There have been other wolves that have come into California and left, other pups that were born in the Lassen Pack. We don’t know if they survived or where they are. Right about this time, we have about 30, 32 wolves in California that we know of.

“Right about this time, we have about 30, 32 wolves in California that we know of.”

-Amaroq Weiss

What are the immediate prospects for wolf reintroduction in Colorado in the wake of Proposition 114’s victory in 2020? People voted for more wolves, which is kind of unusual.

Proposition 114 itself has a really fascinating history. It’s the first time anywhere that it’s been put on the ballot for people to vote on whether or not to restore wolves. So that’s unique all by itself. When polling was done initially, there was overwhelming support for wolf restoration. But once things started getting closer to the election time, the anti-wolf forces put all their time and money into pumping misinformation out to the public, like wolves being the “scourge of nature” and “they’ll destroy everything we have.” The vote ended up being really, really close, the polls earlier had reflected 70-80% support for wolves, but it ended up being nearly a 50-50 tie with the winning votes to restore wolves being just over 50%. 50.91% in favor of wolf reintroduction to 49.09% against. The anti-wolf forces were already really strongly coming into play at that time. The good news is it did get passed!

The next step in a process like that is for the state to develop a plan of how they’re going to restore wolves and reintroduce them. And realize, restoration doesn’t always mean reintroduction, it can mean you put legal protections in place that will allow wolves that are already dispersing in to have the safety they need to be able to develop packs, find each other and thrive. I always caution around the “R word.” The R word reintroduction is one way to get wolves back, by picking up wolves from a particular area, bringing them to a new place you want them, and releasing them there. That’s exactly how the Yellowstone reintroduction was done. And also wolves were reintroduced to central Idaho at the same time as the Yellowstone reintroduction, bringing wolves from Canada down to Yellowstone and central Idaho. The process of reintroducing wolves from Colorado, which is what the ballot calls for, is going to require getting wolves from other locations. And I understand the state wildlife agency in Colorado is already working with the federal wildlife agency to determine where to get those wolves from. I think they’re looking at the Northern Rockies, but also possibly eastern Oregon and eastern Washington.

Beyond capturing wolves and reintroducing them, whenever wolves are going to become part of the ecosystem in any state again, that state tends to develop a state wolf management plan. Colorado just did that and came up with their draft. It’s unfortunately not a plan that we can support, it is really not based on sound science, it’s based on anti-wolf sentiment. Oftentimes when you read state wolf plans, you can clearly see the tone that wolves are an obstacle to overcome, instead of a conservation opportunity to embrace. That’s really, really common in state wolf management plans, and we’re seeing that in the Colorado plan as well. There’s public comment that’s been going on, and what that plan ends up being in its final form, I don’t know. I don’t know how much leverage conservation groups actually have to make it a better plan, but we hope so. One of the things that’s likely to happen in that state-it’s a little wonky to describe. Under the federal Endangered Species Act, if a species is listed as fully endangered, it can’t be killed except for in defense of human life. And if a species is listed at a lower level of protection, called “threatened,” then the agency also writes up a bunch of rules that allow other circumstances under which that animal can be killed. For instance, livestock conflicts. If the species is listed as endangered in an area, not threatened, that means it’s fully protected. So what the agency will do to get around that is give it a new designation, called Section 10-J of the Endangered Species Act. And that’s what they’ve done when they’ve reintroduced wolves to places. And that Section 10-J treats them as though they were threatened instead of endangered, which means they can be killed under a lot more circumstances.

Wolves right now are federally listed as endangered in Colorado. If the state wants to be able to kill wolves, for livestock conflicts, the only way that can happen is if the federal agency does the reintroduction as a Section 10-J population, and that’s what they’re planning to do. So we already see in Colorado, the first thing they’re trying to do is figure out how are the all the ways that we can be able to kill wolves. Which is not a good starting place! Not when you’re a wolf and not when you’re a conservation group. So that’s why it’s important to also have very protective state laws. Here in California where wolves are coming in, even if federal laws disappeared, we have a really great state endangered species act that they’re protected under. So I think the Colorado effort really has a lot of very thorny issues to overcome, and I don’t expect to see things smoothed out anytime soon. There will definitely be a number of legal battles that will happen. You and I will just get to watch it play out.

What do you think of the fascinating new study on the effect of Toxoplasma parasites on gray wolves in Yellowstone? That blew my mind! Does that play into conservation at all? Are people still figuring out what the ramifications are?

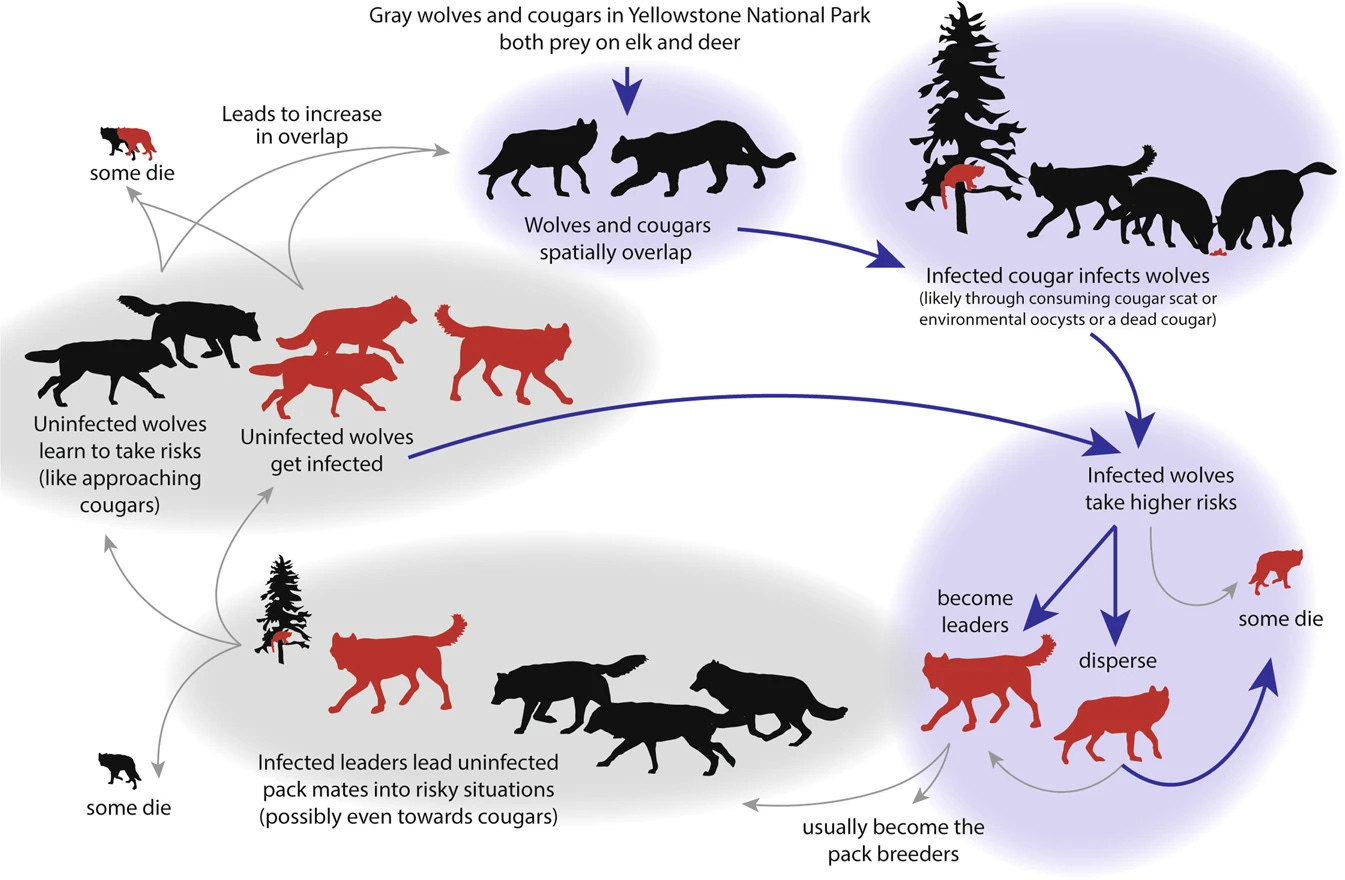

The very first thing I thought about when I saw that was comparison to some entomology work which has been done. There’s a fungus [Cordyceps] that basically makes ants act like a zombie. And so I thought, this is fascinating to read of another little parasite affecting the behavior of its host species. The work in Yellowstone, there’s so many great studies coming out of there. So much work coming out that’s taught us more about wolves than we ever knew. The Toxoplasma gondii study (here’s the full study) is just fascinating. It basically says wolves and mountain lions are sympatric, meaning they share habitat. Wolves likely contract the toxoplasmosis parasite from the mountain lions. Any of us who have grown up in a household with cats, we’ve known that if you’re pregnant you shouldn’t change the cat litterbox, you can get toxoplasmosis from the scats and that can cause reproductive issues.

Same thing here with a tweak on it, with the wolves and the big kitties, the mountain lions. Wolves contracting toxoplasmosis from mountain lion scat. It seems to create a situation where the wolves that have contracted that disease engage in more risk-taking behavior. They tend to disperse more than other wolves do, and that is a very risky behavior. Being a dispersing wolf is really risky, you’re out there on your own, you might get kicked in the head by an elk if you try to hunt by yourself, there’s so many things that can happen to a lone wolf. The effect of toxoplasmosis seems to make wolves disperse more often or further, and on top of that it seems to make them end up being the leader of their pack. And I think the theory behind that was that the toxoplasmosis infestation may increase the testosterone levels of the animal, which makes them a more aggressive, more assertive animal, more likely to end up being the pack leader.

Another takeaway from that for me is something I always try to convey to the public. Yes, wolves are super important, but everything in the ecosystem is super important! We talk about things like impacts. I view nature as a tapestry, with all these intricate threads woven into it. You start pulling the threads out, the tapestry weakens. You weave threads back in, it’s rich fabric of nature again. It’s all of it, it’s wolves, fire, climate, soil, moisture, top-down, bottom-up. A study like this that comes out of Yellowstone reminds us of how intricately woven everything is.

“It’s all of it, it’s wolves, fire, climate, soil, moisture, top-down, bottom-up. A study like this that comes out of Yellowstone reminds us of how intricately woven everything is.”

-Amaroq Weiss

Maybe we thought somebody became a pack leader just because they were born that way, but maybe not, maybe they got infected by toxoplasmosis. That’s what science is really good at doing, you see a question, you learn what the answer is, and it makes you ask more questions.

What, in your expert opinion, is the current political and ecological potential for future wolf reintroduction efforts, perhaps in New England or other sadly wolf-less states?

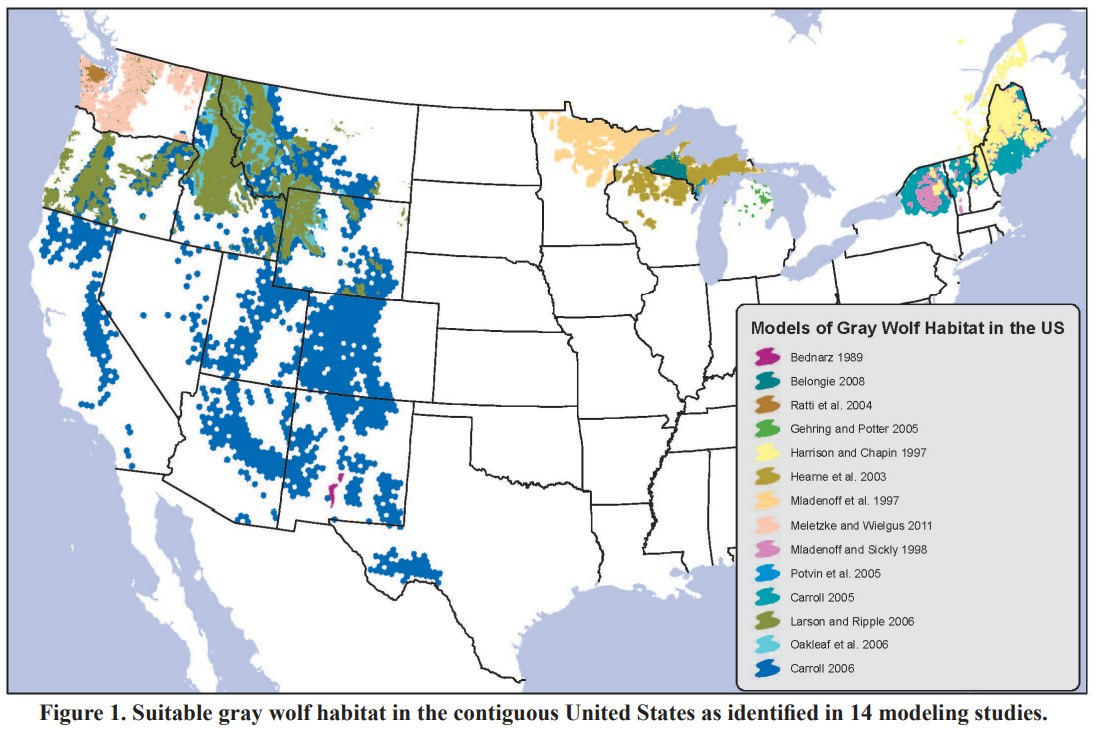

I think that there’s ample opportunity for wolf restoration in other parts of the country. I’m not convinced that there’s lots of opportunity for wolf reintroduction, simply because it’s so contentious. When it comes down to a vote or a government agency moving the wolves somewhere…it’s fascinating. Nobody protests when the government agency relocates elk or white-tailed deer to a new region because they’ve been missing from there. If we move large predators, they start running into political battles and opposition. As far as habitat elsewhere in the US, there’s so much wolf habitat still available. We did a study back in 2014 where we analyzed 27 different studies done throughout the country on where there might be suitable wolf habitat. (Here’s the full report). Not everywhere has even been studied, large places in the lower Midwest and the Dakotas haven’t been studied. From the studies we found, there’s 530,000 square miles where the wolves can live, and right now wolves are only occupying about a third of that. And even occupying a third of that, they’re still only occupying about 10-15% of their original habitat, at only 1% of their original population throughout the lower 48 and only about 10-15% of their original habitat.

What makes good wolf habitat is a couple of factors. Is there low road density there, low human activity there? If there’s a lot of roads, they’re more likely to get hit by vehicles, and people can drive into areas and shoot them. Is there a prey base available? How abundant and dense is the prey base? Is there forest cover there? Forest cover provides refugia, safe habitats for wolves where they’re not going to be coming up against humans all the time who want to kill them. But also, that forest habitat goes to edges of open fields, and that’s really good habitat for elk and deer which wolves need to eat. How much agriculture, in livestock, is going on in the area? If there’s a lot of sheep raising in an area, it’s probably not a great place to have wolves. If there’s cattle raising going on in the area, wolves can actually live fairly peacefully with cattle, for all the headlines in wolf country about wolves decimating the livestock industry. It’s simply not true.

The Northeast is a really intriguing place. Years ago, the US Fish and Wildlife Service was considering developing a wolf recovery area in the Northeastern states, New York, New Hampshire, Maine, Vermont, and then they backed off of that. Probably due to political pressure to just stop doing wolf recovery anywhere else. But I’m actually working with a group of people, the Northeast Wolf Recovery Alliance, and we formed this alliance because just recently, last December [2021], a hunter killed a wolf in upstate New York.

Really?! I did not know this.

Yeah. My colleagues back there-this is how it was found out. The hunter posted about it on his Facebook page, and one of my friends from the Maine Wolf Coalition regularly scours Facebook pages to see if there’s any indication of hunters killing animals which maybe they think are coyotes, but they’re not. And he found this one, and he contacted the hunter, who allowed him to get a sample from the animal, sent it up to Trent University in Ontario, and it came back 98% wolf. The guy had thought it was the biggest coyote he’d ever seen when he shot it. I actually talked to him on the phone, he didn’t know it was a wolf. And part of the reason he didn’t know it was a wolf is that state wildlife agencies in the Northeast do not want to tell the public that there are wolves in the Northeast, that wolves randomly disperse into the Northeast. People have always felt that the St. Lawrence River was a barrier for wolves coming down from Ontario, but it isn’t always. And in fact, this wolf that was killed in upstate New York, the genetics show that part of its genes came from wolves in the western Great Lakes states, part of its genes came from wolves up in Ontario, a little bit came from coyote, and a tiny percentage came from dogs. This is not surprising, there’s been a body of research since at least 2013 that has identified animals on the East Coast that are referred to as coywolves.

That was my next question!

Yes. Dr. Jonathan Way, who used to work with the wildlife agency at Massachusetts, is the person who coined that term. And he’s done a tremendous amount of research. On the East Coast for years, the question was, the red wolves that live a little further south, in the Carolinas, were those really wolves or were they wolf and coyote crosses? And they’ve been definitely determined to be their own species now, the red wolf. Then the question came to be, what are these larger canids we’re seeing further north? Are they large coyotes? Are they eastern wolves? What are they? And what Jon, Dr. Way found was that there’s actually a hybrid species there, that’s about 60 to 65% coyote, 25 to 30% wolf, and about 10% dog. They’re much smaller than the gray wolves you see in the Northern Rockies, they’re closer in size to the eastern wolves you see in Ontario. They’re bigger than a coyote, bigger than a western coyote, western coyotes are usually about 25 pounds at most, although they look bigger than that. These coywolves range up to around 40 pounds or so on average. And all canids, when they have a really full coat, tend to look a lot bigger than they really are.

So, one of the challenges we’re trying to overcome in the Northeast to allow for more wolves that are dispersing in to stay alive, and not be killed by a trapper or hunter who things they got a really large coyote, is to first of all ensure that those states have protections for wolves and coywolves. To consider regulating or banning coyote killing in those states, because most states have completely unrestricted coyote killing. You can kill them any time of year, there’s no bag limit, you can hunt them at night, you can hunt them with hounds. That needs to be regulated or restricted so that you have seasons, for instance, when wolves that are dispersing through may be more vulnerable, you’re not going to have people out there killing coyotes. It also needs to be restricted just to give people that are out there hunting the sense to stop and think. You’re not even in the situation on the West Coast where it’s pretty hard to claim that you thought the 110-pound wolf with a collar that you shot was a coyote. Although people have claimed that, and gotten away with it! It’s going to be trickier in the Northeast, because there is this variation in size. Eastern wolves from Ontario are smaller and more streamlined than are gray wolves. Coyotes are smaller and more streamlined than wolves in general. Really what should happen is those states out there should be protecting all canid species, to allow for wolves to recolonize there.

Since 1993, there have been 11 known wolves killed south of the St. Lawrence River, in Maine, Vermont, New York, Massachusetts, New Brunswick, and Quebec. So there is a real opportunity there. Wolves are trying to make their way back! And what it will take is the state and federal agencies to work together, educate the public, and put protections in place, so those wolves can disperse in and restore themselves.

“Since 1993, there have been 11 known wolves killed south of the St. Lawrence River, in Maine, Vermont, New York, Massachusetts, New Brunswick, and Quebec. So there is a real opportunity there. Wolves are trying to make their way back! And what it will take is the state and federal agencies to work together, educate the public, and put protections in place, so those wolves can disperse in and restore themselves.”

-Amaroq Weiss

I’m really fascinated by the emergence of "coywolves," coyotes with some domestic dog and wolf genes, and the ecological/conservation implications of canine hybridization generally. The legal system wants animals to be cleanly one thing or the other, but the animals don’t. As a lawyer and a biologist, what’s your take on this?

We’re living in a changing world, a world that is so influenced by climate change and experiencing global extinction crises, that I actually expect we may see more hybridization in other species as well, because that may be the way they’re adapting to a changing climate. Not just changing human pressure from human infrastructure and roads and things like that, but actually in response to climate change, because if they don’t hybridize, it may be that they’re gone.

It gets really tricky, in law especially. In law you want to be able to draw very clean lines [for example, whether an animal is part of a species that is legal or illegal to kill]. The hybridization issue makes it quite a bit trickier. I don’t know how that’s going to play out, Sam. The Northeast is probably the perfect cauldron is which to see all of those things mixing together and some of those answers having to be reached.

Can you brief our readers on the current status of the "wolf wars" of the West? I’ve been struck by the vitriol and the violence of the anti-wolf forces, from Republican Montana Governor Gianforte’s illegal wolf killing [Gianforte illegally killed Wolf 1155, a radio-collared wolf from Yellowstone National Park, when it strayed out of park boundaries] to the likely poisoning of several wolves in California to the "killing sprees" in Montana and Wisconsin. You’ve been personally attacked online for supporting wolf populations in Oregon. There’s a very MAGA-tinged undercurrent here. What’s it like dealing with that?

Any of us who have been doing wolf advocacy have dealt with this for years. I have a friend who works in Idaho, and there were some years that different county sheriffs told her that she should not drive through their county, because they could not guarantee her safety. Which would mean she would have to drive five hours out of her way to get to her final destination. I can remember being in some communities where in the hotel I stayed at, I put a towel against the door of my bedroom because other advocates had warned me that people might try to slip some noxious substance into your hotel room. We all get nasty threats by email. I would say anytime somebody writes me some kind of vitriol, if they’ve taken the time to write something more than just “die, you evil ****” if they’ve actually written to me with some complete misunderstanding of how wolves interact with wild elk in their area, I will write them back. I will say, I understand why you might have thought that, but here’s actually what the science is showing. I’m sure you’d love to read about the herd research that’s been done right in the area you’re talking about. Here’s the paper, and you’ll see that they’re finding that wolves in that area aren’t having an impact. Elk are actually moving onto private lands, you’re not seeing them on public lands so you think the wolves have eaten them all. But in fact the agency research shows that elk are at or above the objective in every management area in this state. So there are some times I will attempt to reach back with information. If they’ve bothered to write something longer than “You suck, die” I will write them back.

But you’re right, certainly the passion, the amount of violence in American political issues has really, really increased. There was an article headlined something like “Owning the Libs by Shooting the Wolves.” [Likely The New Yorker’s "Killing Wolves to Own the Libs.”] It described a phenomenon, ever since wolf hunting was allowed in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho, back around 2009-2011 when wolves were briefly delisted and then finally congressionally delisted. [Congress forcibly delisted the Northern Rockies gray wolf population in 2011, removing Endangered Species Act protections and allowing states to legalize hunting them]. People hunting wolves then did want to lure wolves out of the park. They would have been very glad to kill a collared wolf that hundreds of thousands of people had come to the park to see. So that attitude has been around for a very long time, but it has intensified. It does make it more frightening. it makes it worrisome, when going to public meetings, agency meetings. If you’re not passing through a metal detector before you go into that meeting room, you look around the room, and you want to feel assured that someone in there not is armed. I talk to my colleagues, and I don’t think even ten or even five years ago we would have had that worry. It’s more of a worry now. It’s an American thing, tragically.

What are your current upcoming campaigns with the Center?

We have a couple of things already going, and then some things coming up. One thing is, we have a lawsuit filed against the US Fish and Wildlife Service for their failure to ever develop a national wolf recovery plan. Once wolves were listed, they only decided to try to recover wolves in three places, the Northern Rockies, the western Great Lakes states, and the southwest. As I described earlier, there’s hundreds of thousands more square miles where wolves can live. And when you list a species under the Endangered Species Act, you should be doing as much full recovery as possible. So we’re in the midst of that lawsuit, awaiting a briefing schedule from the court. We have really strong arguments that would require the US Fish and Wildlife Service to dig in again and get back in the wolf recovery business.

We have other things coming up in different states. Oregon, its wolf plan that I helped advise on back in the early 2000s, every five years or so it gets revised. That agency ODFW and the commissioner start a process to get input on how to revise the Oregon wolf plan, if changes should be made. In Washington State, I’m monitoring a lot what’s going on there. There’s a very strong push by anti-wolf opponents to get wolves stripped of state protections sooner than what their state wolf plan calls for. So we’re working with colleagues to monitor what’s going on with that, what the political winds are there.

And in California, I’m part of a stakeholder group that is advising the agency on the development of their program to compensate livestock owners for direct losses and provide financial and technical assistance to them to learn nonlethal conflict prevention tools, strategies, and methods that we can put into place to prevent conflicts from happening. And then another component called Pay for Presence, providing some payments under the assumption that, based on some of the scientific research, when wolves are present there can be additional indirect losses. Livestock may suffer from lower reproduction due to stress. They may not gain weight as rapidly as calves normally would in the absence of wolves. Some of that research is still fairly new, but it’s important that it gets done so that it’s not just anecdotal stuff, you don’t want governments making policy decisions just based on anecdotes, you want it to be based on sound research. In the midst of advising the agency on how to put together such a program, we’ll take a look at those factors as well.

There’s always something to look at. Anytime an agency I’m monitoring issues a kill order, to kill members of a wolf pack, there’s always details in their report that are questionable. There will be things like, “You say that the livestock owner had constant human presence monitoring their livestock, but at the same time you say these injured calves weren’t discovered until two or three weeks after you estimate the injuries occurred.” So let’s fill that gap there, maybe it’s not really correct to say this person was using human presence. Maybe the agency tries to bring in another agency to help them with a kill action, and it may be that that other agency actually doesn’t have legal authority to be involved. Any time one of these things comes out, there’s a million details to look at, to see if they’re really following what’s required in order to best conserve and recover wolves.

What questions should I have asked that I haven’t asked? What do you want to share with readers?

The question we should ask: Why is it that when the media wants to write a story about what’s happening with wolves, they so often make it about the ranchers’ perceptions, when in fact the ranching community is such a tiny percentage of the American population, and the amount of livestock killed by wolves is such a minute fraction of a percent of all the reasons for loss of livestock?

“The question we should ask: Why is it that when the media wants to write a story about what’s happening with wolves, they so often make it about the ranchers’ perceptions, when in fact the ranching community is such a tiny percentage of the American population, and the amount of livestock killed by wolves is such a minute fraction of a percent of all the reasons for loss of livestock?”

-Amaroq Weiss

In the United States, the US Department of Agriculture has a program called the National Agricultural Statistics Service, and they gather data that’s self-reported by farmers and ranchers across the country. And what they’ve determined is that for cattle, calves, sheep, and lambs, 90 to 95% of losses are caused by things that have nothing to with any predator of any kind. Things like bad weather, dehydration, starvation, birthing complications, respiratory infections, ingesting poisonous weeds, even cattle theft-there are still cattle thieves. Of the remaining 5 to 10% of losses caused by predators, most of those are caused by coyotes, mostly in the sheep or goat industry. Calves also, but not full-grown cattle. Next in line after coyotes is domestic dogs. Domestic dogs running loose in the country are the second leading cause of predator losses of livestock. After that, depending on the state you’re in, it’s bears or cougars. Then after that there’ll be a smattering of bobcats, eagles, and wolves. Wolves are really low on the list of predator-caused losses. In Montana, you mentioned how aggressive they’ve gotten in Montana, also in Idaho, on wolf-killing legislation and regulations in the last couple of years, that allow greatly expanded means of how, when, and where wolves are killed. One of their chief arguments is that wolves are decimating the livestock industry. Except if you looked at the National Agricultural Statistics Service data, what you learn is in Idaho, wolves kill 0.004% of the livestock. In Montana, wolves kill 0.003% of the livestock. By no means is that putting the livestock industry out of business. It’s certainly a false argument that’s made, and yet in America, because we have such a romantic notion of the West, and of ranchers and ranching culture, people don’t dig deep to find out that information. They believe what they hear, oh they’re wiping out the ranchers. The question I ask you to post, but that I can’t answer, is: how do we change that?

Thank you so much for meeting with me.

You’re welcome.

I believe that ranchers and farmers should protect their interests and they have lots of options to do so. Strategic fencing, herd/crop management, and use of distant monitoring are used by some folks I’ve spoken with. Calves are brought in to protective areas during the time they are most vulnerable to predator attack. I don’t have cattle but do have frequent bobcat, bear, elk and deer visitors who do lots of damage. Mini sheep and goats and fruit trees make tasty treats but fences and dogs keep them out. I feed the bears at a location away from the house and orchard. In my opinion, we can all live together with a little work.

This is fantastic. Amaroq Weiss is the best of the best when it comes to explaining wolf issues. I'm beside myself on behalf of California and its increasing wolf population these days, and I look forward to the day when more of the U.S. is re-wolfified. "Re-wolfify the Earth" doesn't so much roll off the tongue as tangle it up, but at any rate, I like the idea of it. :)