Repost: Review of What Would Nature Do? by Ruth DeFries

A The Weekly Anthropocene Book Review

The Weekly Anthropocene published a review of Ruth DeFries’ What Would Nature Do? in May 2021. The interview is now republished (with a few text & image updates) for Substack!

In "What Would Nature Do?", Columbia University professor of ecology and sustainable development Dr. Ruth DeFries zooms through the stories of human civilization and the nonhuman world to identify key strategies that help systems, from organs to individual creatures to nation-states, survive disruption. It's a slim volume, at 6 chapters and under 200 pages, but positively packed with fascinating history, science, and analysis. The "wow, that's awesome!"-moment-to-page ratio is very high. Dr. DeFries' writing is delightfully playful and variegated, willing to incorporate in-depth analogies and examples from cases as diverse as Isaac Asimov's fictional Galactic Empire, real-world economist Elinor Ostrom's research, stock market crashes, insect hives, Biosphere 2, and anole evolution.

The book centers on four attributes that are characteristic of successful, resilient systems in both nonhuman and human realms. The first is self-correcting features, automatic procedures that kick in when a mistake is made or a problem arises. Animal bodies evolve dozens of these, from sweating when it gets hot to the pancreas releasing insulin when blood sugar is high. Arguably, democratic elections are self-correcting features for human societies: when leadership is really, really screwing up, they tend to get kicked out.

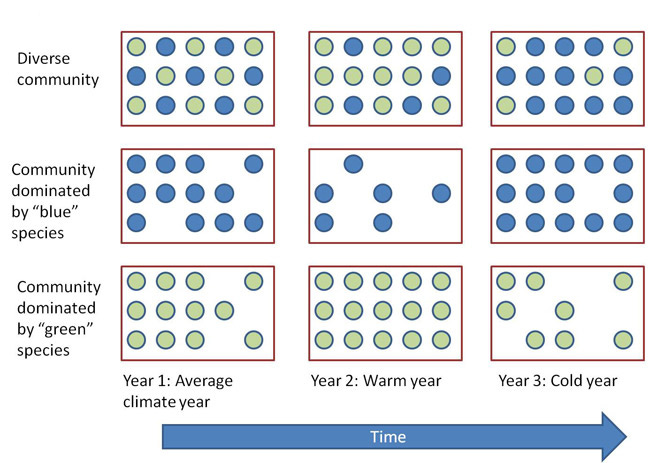

Diversity, "hedging one's bets," is another near-universal helpful feature: species with more genetic diversity are more likely to survive catastrophes and successfully evolve new survival strategies. Ecosystems with lots of different species-from rainforests to human gut microbiomes-are less likely to collapse when faced by an external threat like a drought or antibiotics. And human agricultural systems with a variety of cultivars of food plants are less likely to be devastated by a single new pest or disease.

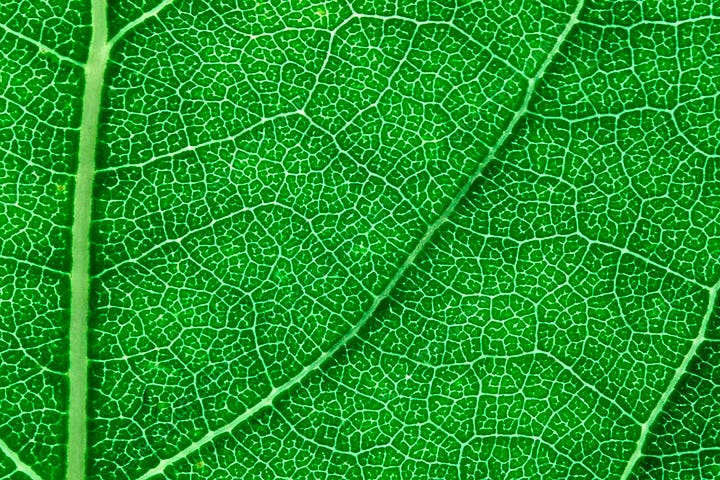

The book's next example is decentralized networks. Most plants' leaves use decentralized networks of nested loops-within-loops to transfer water and nutrients from place to place, ensuring that if one vein gets broken or bitten into there'll be plenty of ways to loop around it without leaving any patch of leaf high and dry. Internet routing uses a very similar protocol, sending packets of information down many different paths so that if one node is taken down the whole system is still operational. However, leaves from certain lineages of plants that evolved earlier, like ginkgoes, rely on a "hub and spoke" model with a lot of straight-line veins radiating out from a central point in the stem. This means that just one tear or insect bite can take out a vein that's the only source of water for a big swathe of the leaf, with no backups. Dr. DeFries makes the insightful point that global food distribution has the exact same problem of relying on a few key paths. When the Bush Administration tried to promote corn-based ethanol as a fuel in the late 2000s (a bad idea for many, many reasons), the flow of edible corn leaving the United States decreased as more was made into ethanol. There were no backup sources of corn for the world, leading to food riots in 2008 ranging from Mexico to Haiti to the Philippines.

And finally, building things from the "bottom-up," with on-the-ground individuals making small-scale decisions that add up to the finished product, almost always works better than imposing a "top-down" plan and expecting all sub-units to make it happen. Bottom-up decision making is how termites and ants build, with workers following pheromone trails to place tiny pellets atop those left by previous workers. It's also how healthy markets work, with individual vendors making thousands or millions of micro-decisions about how, where, when and at what price to sell their product. Interestingly, Dr. DeFries posits that this is also what led to the Paris Agreement being enacted in 2015 when climate talks at Copenhagen in 2009 failed: in Copenhagen, negotiations broke down when nations couldn't agree on what global emissions targets to set, but the Paris talks agreed on the broad shared goals and allowed each nation to set their own targets. That's led to some issues with countries like Brazil under Bolsonaro and Australia under Scott Morrison (both fortunately now replaced) trying to fudge their numbers, but it also made possible human civilization's best-ever platform for fighting the climate crisis.

In sum, "What Would Nature Do?" is a fascinating and mind-expanding book that helps the reader see the world in a different way, with more interconnectivity and similarities across fields of inquiry and scales of existence than before. You won't regret picking it up!

I missed this teview when it came out so this is all new ground to me! A good rationale for reposts in general methinks. Excellent ideas propounded in it- nature, as always is our teacher it seems, a datum the author is quick to pick up on.

The first thing nature would do - and will do - is return us to our proper scale on this earth.