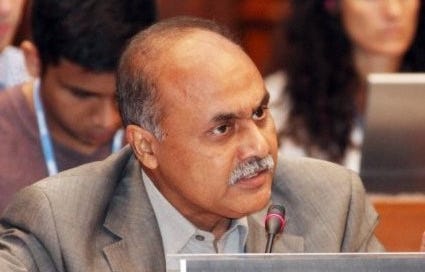

Repost: Interview with Quamrul Chowdhury, Bangladeshi Lead Climate Negotiator

An Exclusive The Weekly Anthropocene Interview, now republished

Quamrul Chowdhury is an economist from Bangladesh who has served as the Lead Climate Negotiator for the UN Least Developed Countries (LDCs) group since 1990.

A lightly edited transcript of an exclusive interview with him follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Mr. Chowdhury’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

This interview was first published in January 2023, and is now republished for a wider audience.

Hi, Mr. Chowdhury, thank you so much for joining us. To start off, could you give our readers a sense of your personal story, your history and leadership on climate change diplomacy? I know you’ve been a lead climate negotiators for the LDCs since 1990-how did that come about? What have the decades since then been like?

I have been in this process since the beginning of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and Sustainable Development, since the Rio conventions in 1992. I was involved in the crafting of the Rio convention’s biodiversity conventions, desertification conventions, and climate change conventions. Since then, I have been in the environmental delegation, in this process, as a lead climate negotiator for the Least Developed Countries and the G77+China. I have been in the process for many years, crafting so many things. LDC Fund, Adaptation Fund, Kyoto Protocol, Green Climate Fund. An international mechanism for funding for loss and damage, the Cancun Adaptation Framework, a national adaptation process for Least Developed Countries.

So, it’s a long history, a long time. And I was also chair of the UN Kyoto Protocol’s Joint Implementation Committee, and also a member of the Adaptation Committee of the United Nations Framework Convention. So many, many things.

Can you give our readers a sense of how things went at the recent COP 27 climate meeting? What are your thoughts on the nascent “loss and damage” funding pledges1, with a lot of work to operationalize it? What are your thoughts on that process?

Climate negotiation is between 200 countries, and many different types of countries. Industrialized countries, middling countries, lower income countries, Least Developed Countries, Small Island Developing States. There are also developing countries as a Global South bloc. The G77 has 134 countries. And we have to negotiate with our partners, the USA, the EU. Then also, after Brexit, United Kingdom. We have to negotiate, and we at the G77+China, we have to also say our common position between Small Island Developing States, Least Developed Countries, middle income countries, oil rich countries, and others. Asian countries, African countries, Caribbean countries, Latin American countries, Pacific countries.

This is a really diverse group of countries. But we have some common denominators. On loss and damage, we have been asking for it since 1990. 32 years. Only this year, we could get loss and damage funds. But it has to be crafted. A transition committee hopefully will do that. Before that, we had the Warsaw International Mechanism (an early acknowledgement of loss and damage as an issue, with no specific provisions for compensation). We created that in 2013 in Warsaw. The adaptation committee was created, an Adaptation Fund for developing countries, was created. And also the Green Climate Fund, for climate change actions in developing countries was crafted. $100 billion dollars (per year) should be released by 2024. But, you know, 2022 is now ending, and it’s coming fast.

So three years, at least 300 billion dollars should be mobilized already and disbursed. But that was not the case. So there is a gulf between promises and disbursement, taking actions on the ground, concrete adaptation actions or mitigation actions on the ground in developing countries. A lot of things need to be operationalized. Market mechanisms are yet to be operationalized in practice. Cutting back emissions is of paramount importance. If we don’t cut back emissions fast, steeply, and especially G20 countries, if they don’t cut back their emissions in the next two to five years, then no adaptation will be enough. The IPCC 6th Report pointed out that the soft limit of adaptation is now almost exhausted, almost finished. And the hard limit of adaptation is also approaching fast. We need to scale up mitigation efforts, cutting back emissions as fast as possible, so that that 1.5 degree Celsius Paris Agreement global goal stays alive. It is now, in, say, life support.

So, that life support system, we must address that. Otherwise this climate emergency will persist. And that will not help rescue billions of people who are on the hook of adverse effects of climate change in very many countries. In the Least Developed Countries, in the island countries, in the coastal countries, in the Asia-Pacific countries, in the Latin American countries, in the African countries. We have to address that. For that, we need trillions of dollars. Adaptation is a trillion-dollar scale. And that level we are talking about, this a trillions of dollars problem. Nature-based solutions, community-based solutions, ecosystem-based solutions, mitigation-centric solutions, we need all this. We need to invest a huge amount of money, a Marshall Plan level spending. Like after the Second World War, the Marshall Plan came in and rescued very many countries. We need it in that way, in that magnitude.

We have to invest in renewable energy. With the Russia-Ukraine war, we have to fix our houses, we have to fix our energy situation, we have to go for renewable energy. And nature-based solutions, and a biodiversity framework at COP 15 (the biodiversity-focused 2022 COP15 held in Montreal, different from the climate-focused COP27 in Egypt), a new framework for halting biodiversity loss is of paramount importance. And also we need to look at, explore, nature-based solutions. Because we are not only in a climate emergency, we are in an environmental emergency. We have to address all those things. That is the way we have to approach it, because billions of people are now at risk. We have to explore and try to resolve as fast as possible, because we don’t have another planet. We have only one Mother Earth, and it is at risk. So we have to save it. We have to have a rescue mission, emergency actions. And for that, we have to have a robust architecture of climate finance, climate adaptation, and climate adaptation plans. Everywhere, every country, every region, we need to do it.

“We have to have a rescue mission, emergency actions. And for that, we have to have a robust architecture of climate finance, climate adaptation, and climate adaptation plans. Everywhere, every country, every region, we need to do it.”

-Quamrul Chowdhury

And also we need to revisit the NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions, the Paris Agreement emissions reduction pledges) of G20 countries, the richest countries, the most industrialized countries, because they need to lead from the front. We are at the receiving end. My own, country, Bangladesh, we are not emitting much. Not even half of one percent (of global emissions). But we are facing a lot of adversity from climate change, every year, every day. Every season. Our economic growth is eroding because of climate adversities. Erratic rainfalls. Land degradation. Water pollution. A shortage of water. Water security, food security, health security, livelihood security. We must address all those, and the global community must support the developing countries, must support especially the Least Developed Countries, the climate vulnerable countries, and the Small Island Developing States. All developing countries. For that, we need a lot of collaborations, a lot of partnerships, global partnerships. We are not advancing fast.

So COP27, it was like, half glass full, half glass empty. Most of the things have been pushed to next year, COP28 at Dubai, UAE. And also COP29, 2024. So 2023 and 2024 are also very busy years coming up, and for that we need to try to take all actions. And for that, President Joe Biden, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, Macron, all of them should come forward, and try to make bold decisions, pragmatic decisions, visionary plans, programs, actions, robust architecture. Without that, we can’t rescue billions of people all around the planet. We must act right now, right here, everywhere. Every country, every continent, every community, every ecosystem.

“We must act right now, right here, everywhere. Every country, every continent, every community, every ecosystem.”

-Quamrul Chowdhury

This all has consequences in the developing countries, in the coastal countries, in the island countries. In the sea level, our ocean, our air quality. So all these we need to address together. Because we have only one planet. Our future generations won’t excuse us, won’t pardon us, if we fail to take bold actions, right actions, pragmatic actions, looking ahead to 2030, 2040, 2050, even beyond that.

That is a stirring call to action.

What are your thoughts on the global climate impact of America's Inflation Reduction Act? It’s a step towards bold action, with its investment in renewables development. How are people viewing that in the G77 and LDCs group?

I think President Biden’s actions are mostly domestic actions. But that domestic action is also a conservative action. He needs some more bold actions, strong actions, and also on international fronts he needs to lead from the front and try to support the developing countries. He should mobilize from the United States $200, $300 billion dollars for climate in the next two to three years. But he’s talking about a drop in the ocean. He’s talking about $1 to $5 billion dollars. The scale and magnitude of the problem is so huge, he needs to mobilize that resource for the whole world. For developing countries, especially climate vulnerable countries, least developed countries. The US alone should mobilize a couple of hundred billion in the next two to three years.

Your country Bangladesh has done some extraordinary work on climate adaptation and resilience in recent years, and you personally have been a real leader on that from the beginning. You were a lead author on the 1995 Bangladesh National Environment Management Action Plan, the 2008 Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan, and the 2015 Bangladesh Roadmap to National Adaptation Plan. And you were just recently at the launching of the Locally Led Global Adaptation Center in Dhaka in 2022. Can you tell our readers more about all that Bangladesh has done, from community shelters to storm warning systems to floating gardens?

You see, Sam, since the 1990s, things are not moving. We are on the front lines. So we have to survive. That’s why Bangladesh prepared its National Adaptation Program of Action in 2005. Then we have had our Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan in 2008, 2009. Then, this year, we have also formulated our National Adaptation Plan. Why? Because we need to do some adaptation work in our country. And we have created a Bangladesh Climate Change Trust Fund, in 2008, 2009. And almost a couple of billion dollars, we have spent for adaptation, over the years. Bangladesh alone. From our own national resources, diverting some money from our anti-poverty problems. Some vulnerable community problems. Because adaptation is a high priority here. We need to adapt ourselves.

But as you know, adaptation has a limit, and already a soft limit is exhausting, and the hard limit is approaching fast. So we need to mobilize our domestic resources. And that’s why community-led or locally-led adaptation programs and the locally-led adaptation hub was set up already here in Bangladesh, to promote that. So that we can exchange information, we can share our knowledge, and try to scale up locally-led adaptation, and community-led adaptation, and ecosystem-based education. As you know, adaptation is location specific. That location is a city, we need to address how its ecosystem is quite different from, say, coastal ecosystems. Or upland ecosystems, mountain ecosystems, delta ecosystems. These are altogether different ball games. We need to know local communities and indigenous knowledge, traditional knowledge, all those need to be harmonized and synthesized to try to make our own best practices and solutions. That should be learned, lessons learned. And also, the early warning system is working, [we need to learn from] what is working, what is not working. Those are trial and error matters we have to also practice here. So that way we need to move ahead, move forward, move fast. Because we don’t have enough time. We need to aggressively address this emergency that we’re each confronting before us.

You’ve edited a report on the state of the Sunderbans. Can you tell our readers about these fascinating, tiger-rich, carbon-sequestering wetlands, and how they’re threatened by climate change? There’s saltwater rising, there’s a bunch of different stuff going on there. What’s the latest from the Sunderbans?

You see, the Sunderbans, the largest mangrove forest of the world, is like our first-order defense line. Hurricanes like 2007 Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm Sidr, 2009 Severe Cyclonic Storm Aila, 2008 Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm Nargis, 2008 Cyclonic Storm Rashmi, 2020 Super Cyclonic Storm Amphan, every time Sunderbans protected millions of people as a first-order natural shield to cut back intensity of these typhoons, hurricanes. So that way it was a first-order defense line. It is our resilience power, our regeneration, our protection. And also Sunderbans is a carbon sink, absorbing carbon dioxide.

So, in a way, Sunderbans is like both mitigation and adaptation for Bangladesh. Especially our coastal southwestern part of Bangladesh is benefited by the mangrove forest of Sunderbans. And it also gives a lot of livelihoods. It’s a World Heritage Site and we need to protect it. But it is also at risk, because of climate change, because of sea level rise and saline intrusion. And also a shortage of sweet water (fresh water) in the dry season. We are facing a lot of problems to protect our Sunderbans. It’s a huge, huge issue. We need to conserve Sunderbans. But that also depends on resources, so a resource-hungry, resource-limited country like Bangladesh can’t afford it alone. We need global support.

Speaking of global support, what are your thoughts on the Indonesia Just Energy Transition Partnership, the new deal agreed to at COP27 where rich countries help fund Indonesia’s transition away from coal? Do you think this could be a model that spreads?

We need not only good intentions, but good partnerships, prudent partnerships. That is what is missing. Even at Montreal COP15, we’ve failed to agree on a new funding mechanism. A new fund for biodiversity loss, a support mechanism to help. Goal 17 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals is partnership, cooperation. But how far do we advance? We’re doing some trickle-down efforts, that model will not work. We need trillions of dollars. The new Indonesia partnership is a couple of billion dollars. That will not be helpful enough.

What would you like to add? What question should I have asked that I haven’t asked?

If we want to do some meaningful work, especially creating a robust architecture for market mechanisms, we need to do a lot of things. To shield the integrity of the market, so there is no double-counting, there is transparency, there is accountability, there is no fraudulent practices. All those we need to enshrine in our new architecture of market mechanisms, along the line of Article 6.2, Article 6.4, Article 6.8 of the Paris Agreement. Full text of the Paris Agreement here; Article 6 is on pages 7-8 and discusses in a general way the creation of funding mechanisms for climate change mitigation and adaptation. That way we need to move past, we have to learn lessons from the vast mistake of the Clean Development Mechanism under the Kyoto Protocol, our joint implementation under the Kyoto Protocol. The CDM was beset by fraud and then collapsed in 2013.

So we need a collaborative approach, we need to have a partnership and try to cut back our emissions fast. Because mitigation is the best form of adaptation. Adaptation is a function of mitigation. The more we mitigate, the less we need to adapt. The less we mitigate, the more we need to adapt. But adaptation has a limit. And the IPCC R6 (IPCC Sixth Report) scientists come out loud and clear that the soft limit of adaptation is now almost finished, and we are now fast moving to the hard limit. So we must be very careful.

Thank you so much.

Thank you.

Including the $200 million-plus in the new Global Shield insurance initiative and the one-to-one pledges from New Zealand, Belgium, and Austria.