Missives from Mesoamerica #3: The Magical Pacific

My third article reporting in-person from Mexico.

As I continued my multi-month remote-work and on-the-ground reporting journey through Mesoamerica, I was fortunate enough to be able to take a local whale-watching boat tour into the Pacific Ocean on March 17, 2025. We left in the early morning from the beach of San Agustinillo on the Pacific coast of Oaxaca state1, a brisk walk from the charming yurt-and-outhouses campsite where my traveling companion and I were staying2.

The boat tour company was a delightfully small-scale local operation, a couple folks running a beachside business with just a couple of boats, each about five to six meters long or so, which they pulled up well above the high-tide line when not in use. Tickets were astonishingly inexpensive, approximating the price of one day’s lunch in a U.S. coastal city. As we waited for the rest of the tour passengers to arrive, beautiful fork-tailed black magnificent frigatebirds were circling overhead. When all the paying passengers had arrived and the day’s voyage began, our boat was up on the San Agustinillo beach well away from the water, and everyone going on the tour joined in to help push the boat down the sand from the beach to the sea — an endeavor greatly aided by strategically placed plastic rollers. Our guide and pilot, Diego, engaged the motor and set forth into the sea.

It took a while for the boat to motor far enough away from the shore to see any large ocean denizens, but I was already grinning ear to ear at just being out there on a small boat on the Pacific. I’d grown up in New England and grown familiar with the Atlantic, but just the knowledge of being in this ocean again, the planet’s largest, brought me a thrill.

Our first major wildlife encounter was completely unexpected — for me, at least. In the middle distance, we saw a clearly recognizable manta ray jumping out of the water, its somersaulting form silhouetted for a precious second against the distant seaward horizon. I had never seen a wild manta ray before, and I was enchanted. I remembered reading that while there were many hypotheses on exactly why whales and dolphins sometimes “breached” and jumped out of the water (ranging from smacking off skin parasites to scouting for distant prey fish swimming near the surface) one underrated possibility was that it simply felt good and was fun for them. I wondered if the same was true of manta rays3.

This delightful amuse-bouche enlivened the entire swath of ocean before us with tantalizing possibility, and it wasn’t long before we saw another show-stopping sight. This next wildlife encounter was the big one, both literally and figuratively.

“¡Ballenas!”

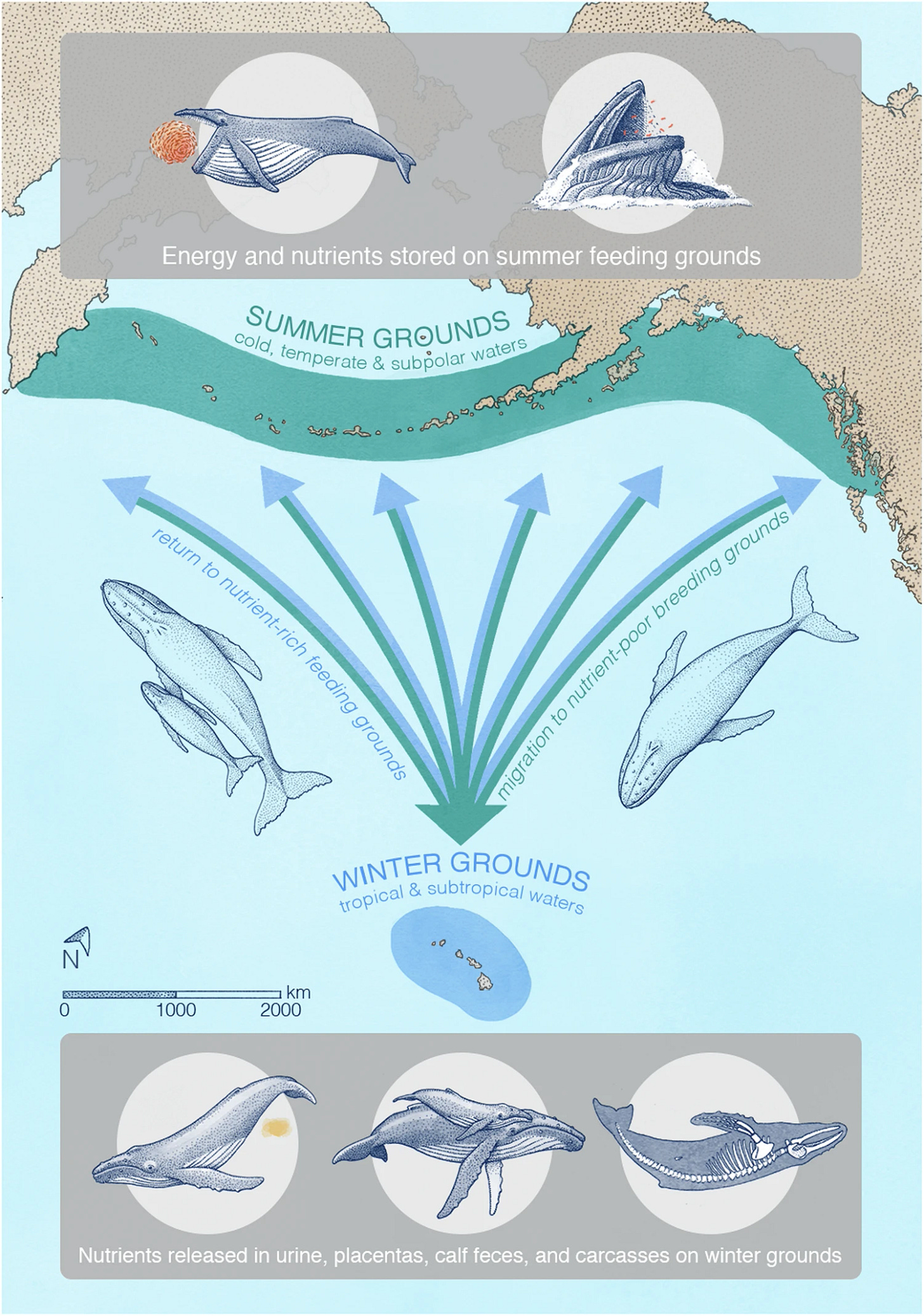

Humpback whales, the majestic Megaptera novaeangliae! We saw a pair of them, although I never got a photo of more than one above the surface at once. I had known that mid-March was the was the tail end of their breeding season, which many humpbacks spent in the warm Pacific waters just off Mesoamerica, and had fervently hoped to catch a glimpse before they swam north again to bubble-net and baleen-sieve fish from the rich waters around Alaska. Now I was seeing two — well, parts of two, the backs and blowhole spouts and occasionally the tails — and I was immensely satisfied. To me, this species has always been the classic archetypal whale, the darling of innumerable nature documentaries I devoured as a kid. Now here I was, seeing them in person.

Humpback whales are a cosmopolitan species; they live in pretty much all the non-iced-over parts of the world-ocean from Greenland to Indonesia to Antarctica. For centuries, they were mercilessly hunted across the world-ocean as well, first by sailing ships (often out of New England) in the style immortalized by Moby Dick, then at a much more rapacious scale by industrialized slaughterhouse fleets in the 20th century. The Soviet Union whaling program alone killed over 500,000 whales — half a million sentient beings — in what has been called “the most senseless environmental crime of the 20th century.” Only a few decades before this writer’s birth, it looked very probable that humpbacks — and all the other big baleen-bearing whale species from blue to sei to fin to minke whales — would be exterminated by human greed.

But things have gotten better for Earth’s whales in recent decades. Much, much, much better. After years of daring direct action campaigns on the high seas by activists such as Greenpeace4 and Sea Shepherd, the International Whaling Commission voted in 1982 to institute an International Whaling Ban which came into effect in 1986 and remains in effect as of 2025. Commercial whaling is now legal in only three countries worldwide which haven’t adopted the global ban5 (Iceland, Japan, and Norway) and their remaining whale-killing, while atrocious, is a tiny fraction of what the world’s cetaceans once suffered, as consumer demand for whale meat in those countries is declining sharply.

The result has been a global renaissance of the great whales, with species after species climbing back from the brink of extinction6. Over 700,000 whales (of all species) were killed by humans in the decade of the 1960s, compared to less than 40,000 in the three decades of the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s combined. An estimated 16,246 humpback whales were killed by humans in 1959, plummeting to an estimated 6 (six) humpback whales killed by humans in 2018.

Humpback whales in particular have bounced back in a truly spectacular manner since the whaling ban. The humpback population in the western South Atlantic fell from an estimated 27,000 individuals in the 1830s to a low of just 450 individuals in the 1950s, but has since risen again to near 25,000 individuals in the 2010s — and very probably more by now. The IUCN estimates that there are 84,000 mature adult humpback whales and 135,000 humpback whales total worldwide as of about 2018 (very possibly more as of 2025!) and now rates the species “Least Concern.”

Humpback whales are returning to their pre-whaling high population densities around the subantarctic island of South Georgia, once a major killing site, and are even living in New York Harbor these days, feeding on menhaden fish in the now-cleaner urban waters and gladdening the hearts of whale-watching borough dwellers. Many other species of baleen whale appear to be experiencing similar, if slower, epic population rebounds.

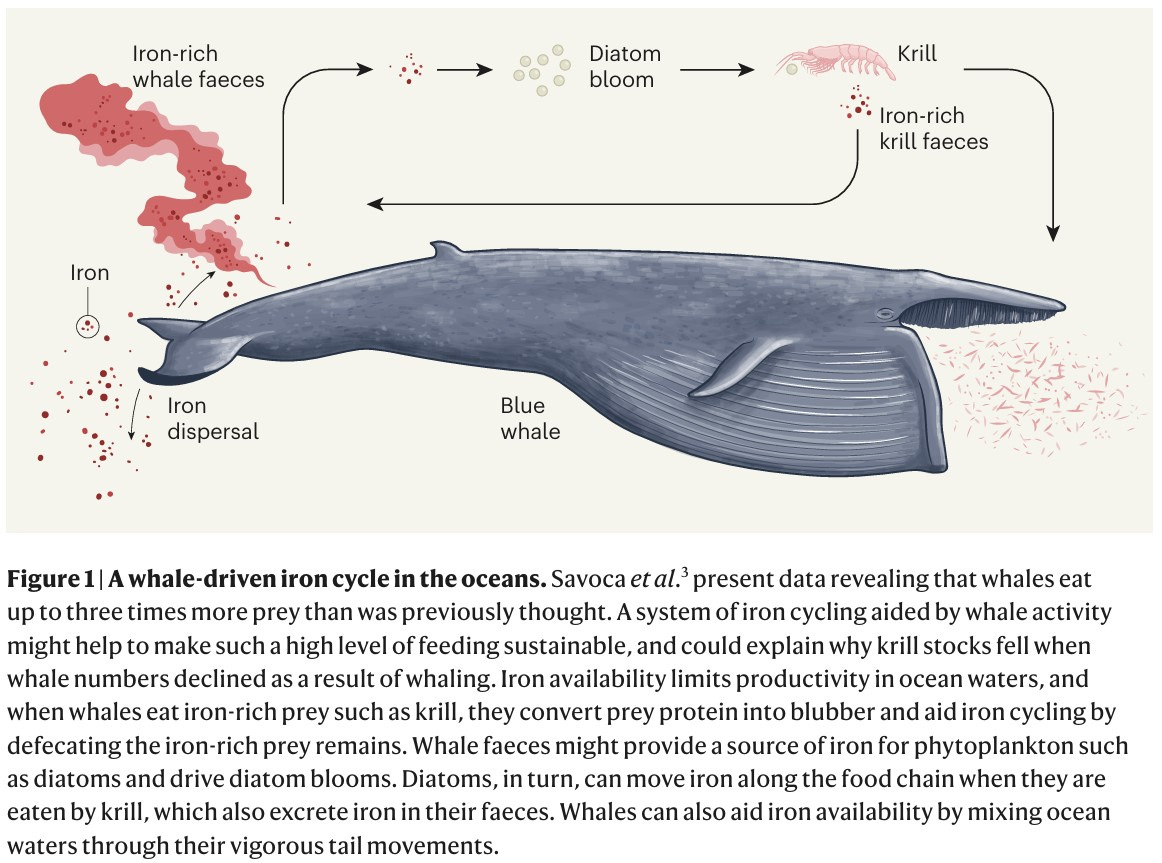

Simultaneously, we’re learning more about the importance of these whales for the rest of the planetary biosphere. As I wrote in a March newsletter just after seeing humpbacks in person, it’s been known for years that whale feces play a vital role in Earth’s ocean ecosystems and climate interactions, with cetaceans feeding in the deep and pooping near the surface providing vital fertilizer for mass carbon-sucking phytoplankton growth. More recently, a new study added fascinating data on the underestimated role of whale urine.

In short, big whales pooping moves nutrients upwards in the oceanic water column, while the migration of other big whales makes their urine move other nutrients across different geographical areas of the ocean. This kind of thing is hard to measure, and it’s an area of substantive and ongoing scientific debate, but there’s a rough consensus that cetaceans moving nutrients around in the ocean probably plays a very important role in regulating Earth’s carbon cycle (although the magnitude of this effect is uncertain and widely contested) by fertilizing the tiny plant-life of the oceans. Those phytoplankton then “eat” carbon dioxide via photosynthesis, forming their bodies with the resulting carbon-based molecules, and when they die they sink to the bottom of the sea and sequester that atmospheric carbon in the anoxic abysses for millennia. One could even anthropomorphize to say that the whales are “gardening” a majority of the planet’s surface, and even though we don’t know just how big an effect this is, we do know that we definitely want to be removing carbon from the atmosphere as much as possible in the age of climate change. The Great Whale Renaissance looks like it’s happening right when the rest of the biosphere really needs it!

There were several tour boats watching this pair of humpbacks from a respectful distance, with throngs of excited passengers photographing their every blowhole-spout and tail-slap. Eventually, the whales dived again, and the boats moved on.

Imagining that the luck we’d just had couldn’t last, I soaked in the afterglow of seeing wild humpback whales without thinking much about what else we might see. I already felt that the entire morning voyage had exceeded my highest expectations as we continued to cruise further away from land.

Then I heard cries of “¡Tortuga!” “Sea turtle!”

I wasn’t sure what I was seeing at first. It was undeniably real, but looked at first glance like the surreal images generated by early AIs like DALL-E. I seemed to see a ball of recognizable sea turtle-ness that somehow didn’t actually form a real sea turtle, with intertwined heads and flippers sticking out at odd angles and two different shell curves emerging from the water. Diego helped us realize what we were looking at.

It was not one but two sea turtles, a mating pair in the act of copulation! I was incredibly lucky to witness this rare sight in the wild. I was surprised to learn that sea turtle mating is quite the impressive endeavor, lasting as long as 24 hours (!) and with the male's penis half the length of his shell once fully emerged from the cloaca.

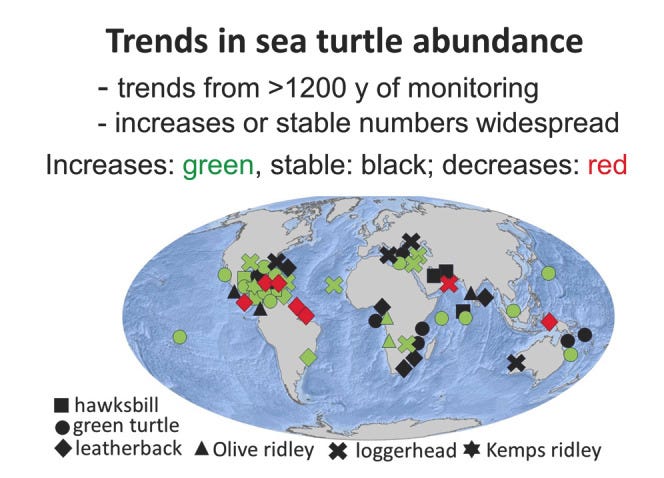

My trusty citizen science app iNaturalist later identified them as olive ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea), one of Anthropocene Earth’s seven sea turtle species along with green, hawksbill, loggerhead, flatback, Kemp’s ridley, and leatherback sea turtles. As I was writing this article in April, a long-awaited global survey of sea turtle populations was published. I had already read and written about some earlier “pulse check” preliminary results in January, fresh in my mind when I saw the olive ridleys for myself.

I was happy to learn that six out of the seven sea turtle species (all except the behemoth leatherback, which still needs more protection efforts) are experiencing substantial population recovery across much of their range, bouncing back thanks to years of conservation actions including protection of nesting beaches and banning trade in sea turtle parts! It’s profoundly heartening to know that the planetary biosphere I live in contains more sea turtles now than it did a few years ago. Another great underreported example of serious problems seeing serious improvements thanks to the hard work of multitudes of ordinary people!

Diego then pointed the bow of our little boat towards the horizon, and we cruised further out into the sea for a while in search of more fascinating creatures to ogle. By now, we were several kilometers out, and the rocky coast behind us was a blurry smudge. Fairly often, we’d see other small wildlife-watching tour boats passing by, and Diego would use his walkie-talkie to exchange information with the other guides about what interesting stuff they had seen and where.

All of a sudden, someone shouted “¡Delfines!” “Dolphins!”

In an astonishingly brief space of time, a pod of perhaps a dozen pantropical spotted dolphins (Stenella attenuata) had crept up to investigate our little boat, half-leaping out of the water, swimming around and under us, and lounging just under the surface of the clear ocean water an arm’s length away from the hull. I’d previously seen baleen whale tails in the Gulf of Maine and the distant silhouettes of leaping dolphins on the horizon off New Jersey (not to mention the two humpback whales just now!) but this was by far — incredibly by far — the best viewing I’d ever had of wild cetaceans. I was surprised at how small these particular dolphins were; I’d expected a higher body length than an average human, but many of these seemed visibly shorter, maybe between four and five feet long (around 1.3-1.6 meters). Maybe juveniles?

This group of dolphins seemed curious at the very least, perhaps even friendly. Our boat wasn’t feeding them or anything, and they’d surely seen tour boats many times before, but they lingered for what seemed like at least a quarter of an hour, just swimming around and under and besides the boat right next to us. Perhaps they liked to watch the weird monkeys waving at them; perhaps we were their equivalent of a YouTube cat video, a moment’s harmless pleasure watching creatures immensely different yet warmingly familiar. We gloried in their attention for what felt like a summery sunlit subjective eternity, soaking in the presence of these beautiful, playful creatures.

The pantropical spotted dolphin is known for their association with schooling tuna, and were slaughtered in massive numbers in the mid-20th century when caught as accidental bycatch in the purse seine nets of voracious tuna fishing fleets, which would sweep up entire pods of dolphins when encircling the vast schools of tuna. An estimated nearly 5 million of this species of dolphin alone were killed from 1959 to 1982, with 3 million of those horrific deaths in the Eastern Tropical Pacific “ETP” waters — exactly where I was seeing them now. After legal battles, the tuna industry had become essentially exempt from the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act, more or less allowing them to kill unlimited numbers of dolphins in pursuit of tuna as long as it was an “accident.”

Then, in 1987, biologist Sam LaBudde went undercover for five months on a commercial tuna ship and collected the first video evidence of dolphin deaths. In 1988, LaBudde testified before Congress, the footage went on TV, and a consumer boycott of tuna started, pushing companies to respond with “dolphin-safe tuna” labeling. In 1990, the Dolphin Protection Consumer Information Act was passed to ensure that dolphin-safe labels were actually accurate, with on-boat observers and data collection required to sell tuna with a dolphin-safe label.

There’s still work to be done — dolphins still die in human nets — but we’ve made a whole heck of a lot of progress! In 2025, the IUCN now rates the species “Least Concern,” reporting that the population decline has halted, that there are an estimated 2.3 million pantropical spotted dolphins now alive in Earth’s oceans (likely many more as they’re hard to count!) and that Stenella attenuata is “widely distributed and globally abundant.”

I was seeing the exact species of dolphins that had been saved by the success of the “dolphin-safe tuna” campaigns a few decades ago. The individuals I was seeing very probably owed their lives to a relatively small group of activists who hadn’t given up, and a much larger group of folks who learned that something bad was happening and changed their consumer choices because they’d heard it could help.

Eventually the spotted dolphins dispersed, and we continued on. Diego had picked up a tip about a much larger pod of dolphins a few kilometers away, and turned the boat in that direction. He told us that if we were lucky, we could just navigate the boat alongside the dolphins, as we had just done with the pantropical spotted dolphins, and then we could just jump into the water and see if the dolphins would let us swim with them.

Sure enough, after some time searching, we came upon a much larger pod of dolphins, mostly visible as quickly appearing and disappearing backs leaping slightly above the water line in flashes of white foam. The iNaturalist community would later assure me that these were common dolphins, Delphinus delphis. I was the first to excitedly jump off the boat as we pulled alongside the pod, fervently hoping that some of them would come closer to me out of interest in hominins paddling around the surface fringe of their domain. But seemingly as soon as I hit the water, there wasn’t a dolphin to be seen. These dolphins weren’t sticking around the boat like their spotted cousins – as soon as we came close and stopped to try to swim with them, the whole pod either dived or swam far away with incredible quickness. The entire pod of at least a couple dozen dolphins went from “movements in the water all around us” to “completely invisible, no sign of them” in seconds. Our guide kept a lookout, and when they eventually reappeared some distance away drove the boat in that direction in the hope that some of them would change their minds and approach. I jumped into the water two more times, more for the fun of knowing that really deep ocean was beneath my feet than anything else, but with each splash even the most distant visible signs of cetacean presence repeated their instant vanishing act. The dolphins simply weren’t in the mood for human company.

I was briefly disappointed, but a moment’s reflection showed me that this was in fact a morally excellent result. This boat tour wasn’t like the viewing experience in a brutal cetacean concentration camp like the infamous SeaWorld: the dolphins we had seen were free sentient individuals with no barriers between them and the entire Pacific Ocean! If they didn’t feel like hanging out with the African ape-descendents like me who were splashing into their home waters, they didn’t have to. We weren’t kidnapping them and locking them in tiny sensory-deprivation tanks a thousandth the size of their normal daily range to get to know them, we were coming to their home and “asking” if they wanted to see us. Even better, the guide boats weren’t pushing it. They weren’t trying to bribe them with fish to or stressing them out by chasing them at high speed: we had just more or less knocked on their notional door a few times, and when they weren’t at home had given up and gone away — a model conservation ethic for ecotourism. There was a delightful egalitarianism to this; it felt like the way that civilized sentient species ought to behave when sharing a planet with each other.

From the moment I set foot back on San Agustinillo beach7 through the writing of this article in mid-April 2025, the memory of this voyage has helped sustain me during a time when reading the news — as is part of my job now — regularly has me feeling gut-wrenching fear and anxiety for the fate of my country and the world.

Seeing humpback whales, olive ridley sea turtles, and pantropical spotted dolphins in the wild, all of which are among the many marine species murdered en masse by humans in the very recent past but now experiencing population rebounds and new forms of coexistence with human civilization, helped me remember that while humanity is undeniably capable of horrific atrocities, we’re also capable of ending them and — at least for a while — learning from our mistakes.

The road to a profoundly better world is always horrendously longer and bloodier and harder than it should be, full of U-turns and switchbacks and detours and pit traps that leave a lot of dramatic wreckage, but really quite a lot of the time, with cleverness and hard work and a bit of luck, we do end up getting there after all.

I hope that this thought helps you, the reader, as much as it has helped me.

Gentle reader, forgive this journey being chronicled somewhat out of proper chronological order. Before March 17th, I had also visited a fascinating conservation project near the city of Oaxaca that definitely deserves its own article, which hopefully should arrive in the near future.

While working! The campsite had WiFi, and I wrote newsletters and made serious progress on my GIS consulting projects from there. The modern globalized digital economy offers unusual opportunities.

While writing this article later, I would learn that manta rays have the largest known brain of fish and pass the mirror test, a classic determinant of animal self-awareness. They might not only be having fun leaping out of the water, but also smart enough to really think about how much fun it is for them!

This writer very strongly disagrees with modern-day Greenpeace on several important issues, particularly their woefully anti-scientific and quite possibly child-killing attacks on genetically modified vitamin-enriched crops like golden rice. Nevertheless, the 1970s-1980s version of Greenpeace eternally deserves immense credit for their heroic and successful efforts to end the mass extermination of several sentient species.

There are several other smaller-scale non-commercial “subsistence” legal killings of cetaceans, often linked to historic cultural traditions in circumpolar human communities, from subsistence hunting in Alaskan Inuit villages in the United States to the notoriously brutal “grindarap” on the beaches of the Faroe Islands. While this writer considers such practices to be morally unacceptable as well (these are big-brained, long-lived, social, singing beings — for me, it’s pretty much like killing and eating a human to survive, terrible even if necessary), high-seas commercial whaling from industrialized slaughter ships is in a league of its own as an interspecies atrocity, and its vertiginous decline is excellent news.

Some species of cetaceans are still severely imperiled, but for reasons other than whaling pressure. For example, the North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) is still critically endangered, mostly due to the surface water-dwelling right whales dying from collisions with ships and entanglements with fishing gear in the shipping-heavy waters off the U.S. eastern seaboard. This behavioral vulnerability is in fact the origin of their name: they were known to 1800s whalers as the “right” whales to hunt because they hung around near the surface and were easier to catch. This same trait makes them especially vulnerable to ship collisions today.

I was so sunburned after this excursion that for days afterward I almost felt that I was wearing my own flayed skin like the Aztec god Xipe Totec. Totally worth it, though!

I'm so jealous of this trip. I have looked into the eye of a humpback that tilted its head up next to our boat in Alaska to look at us and yes, within that eye was immense sentience, recognition, and curiosity.

Respect for all life forms.