Methane leaks, fugitive emissions, and why Turkmenistan is very important

Some background on methane emissions, giving context to why recent news from COP28 and Turkmenistan is a big deal

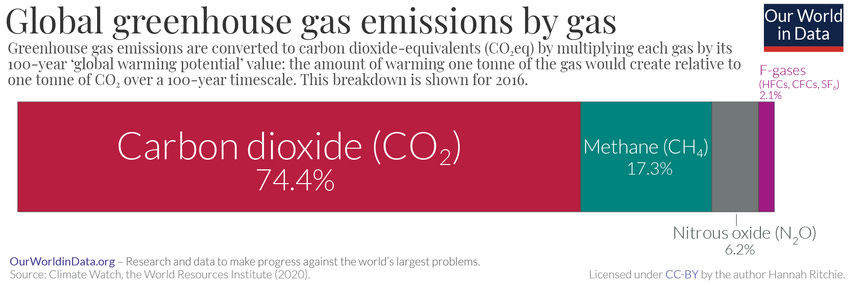

All greenhouse gases are not created equal, and there are a lot of differences between carbon dioxide (CO2, the most commonly emitted greenhouse gas) and methane (CH4, the second most common) in particular. Human civilization emits a lot more carbon dioxide than methane, but methane traps over twenty times as much heat per molecule over a 100-year period. (Note that the greenhouse gas emissions breakdown above from Our World in Data already converts the various gases into “CO2 equivalents”, so it’s showing contribution to global warming, not volume of gas emitted). Methane only stays in the atmosphere for about ten years, though, while CO2 stays in the atmosphere for about 300 to 1000 years1, which is why CO2 is still overall a much bigger issue, climactically speaking. (So if you’re keeping track: there’s less methane emitted than CO2, but methane traps more heat, but CO2 stays in the atmosphere longer.)

And methane emissions have been increasing even faster than CO2 emissions, passing 1,900 parts per billion (ppb) in 2021, nearly triple preindustrial levels. For context, CO2 levels are now at about 420 parts per million (ppm) up from 280 ppm in the 1800s. Note that methane is being measured in parts per billion here while CO2 is being measured in parts per million; one part per million is 1000x more than one part per billion.

Recently, new research has suggested than methane is even more important than we thought. For example, did you notice anything odd in that last paragraph? Methane traps over 20 times as much heat as CO2 over a 100-year period, but it only stays in the atmosphere for about ten years. This discrepancy in time period terminology is because the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) compares all greenhouse gases, including CO2, methane, and more minor ones like nitrous oxide, based on their effects over a 100-year period. However, using this as the yardstick means we’re "averaging out" methane's impact per unit of mass over a longer period, during much of which it's not even in the atmosphere, so we pay less attention to the dramatic short-term impact of methane. Researchers are increasingly calling for the EPA to measure methane's effects based on a 20-year period, over which methane traps 81 times as much heat as carbon dioxide, or a 24-year period, over which it traps 75 times as much heat. The 100-year timeframe isn't wrong, per se. Because methane does go away faster, it does have less of an impact when you look at it in a hundred-year timeframe. But when you zoom in on the next few decades, a critical period for changing our emissions trajectory and determining Earth's future climate, methane looks more important. The plus side of this is that methane’s a bit of a free lunch for humanity in the climate fight: if we cut methane emissions now, we’ll see good results (or rather, slowing of bad results) within a decade or two.

One of the major sources of methane emissions, causing much of the recent increase, is “fugitive emissions,” essentially leaks of methane from oil and gas infrastructure. The good news is that this is fairly “low-hanging fruit” for fighting climate change: everyone has an incentive to solve this problem, and it’s relatively cheap and easy to fix. This isn’t like CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels; a side effect of an energy-generating process that makes money for a lot of people. No one is benefiting from methane leaks; quite the reverse, as they’re wasteful and money-losing. The methane that’s leaking is the same stuff as the natural gas that they want to sell. (To clarify: natural gas is mostly methane, CH4, which when burned for energy produces CO2, but just releasing methane is way worse for the climate than burning the gas. As we discussed above, methane is a considerably more potent greenhouse gas than CO2).

Which brings us to Turkmenistan. Naturally.

Why is Turkmenistan so important to the methane emissions issue?

A 2022 study in Science (here's the paper available for free) used satellite data to find 1,800 "ultra-emitting" events in 2019 and 2020, where 25 tonnes or more of methane were emitted per hour. (Pictured above: a map of those events). These were mostly from oil and gas wells or pipelines, many from accidents or leaks, and added up to 8 million tonnes of methane per year, with a climate impact about equal to the carbon footprint of 18 million Americans. A shockingly large amount of these ultra-emitting sources, emitting 1.3 million tonnes of methane per year, were in Turkmenistan, due to really poorly maintained Soviet-era pipelines and wells. This study was a major step emphasizing to the world that fixing a few aging and/or broken oil and gas wells and pipelines in Turkmenistan might be a cheap way to cut emissions quickly.

In 2023, satellite imagery analysis has revealed that the methane leak situation in Turkmenistan is even worse than thought, with the badly maintained Soviet-era natural gas infrastructure in this one isolated Central Asian dictatorship causing a staggeringly vast amount of greenhouse gas emissions2. Data from satellite intelligence company Kayrros found that Turkmenistan’s western and eastern oil and gas fields together leaked 4.4 million tonnes of methane in 2022. That amount of methane contributes about as much to global warming as 366 million tonnes of carbon dioxide—more than the annual emissions of the United Kingdom. And that isn’t even all the methane leaks in Turkmenistan, as they also have offshore oil and gas platforms that are probably also in terrible shape but are much harder to monitor by satellite. Turkmenistan may be tiny, but its leaky pipes have made it a “superpower” at contributing to climate change.

We’re Finally Starting To Make Progress Here!

So, the fact that Turkmenistan just signed on to a global pledge to cut methane emissions 30% by 2030 at the COP28 climate talks sounds pretty unimportant, but is in fact a major win! And even better (breaking news here!), Bloomberg reports that sources have told them that foreign petroleum engineers have just been able to enter Turkmenistan to start work on curbing methane emissions, likely with diplomatic and economic support from the U.S. government. (The Biden Administration has been trying to negotiate methane emissions reduction efforts with Turkmenistan since early 2023). Within a few years, if all goes well, we could start seeing serious methane emissions reductions as Turkmenistan’s oil and gas infrastructure gets some much-needed maintenance. This is sadly unlikely to get much global attention, but it’s really good news!

Fun fact: the average residence time of a water molecule in Earth’s atmosphere is nine days. For methane, it’s 12.4 years. For carbon dioxide, it can’t be summed up in one value that easily because some CO2 molecules are absorbed by the ocean very quickly while some stay in the atmosphere for thousands of years, but it averages out, broadly speaking, into impacts lasting for hundreds of years.

It’s not that surprising that Turkmenistan can’t muster the institutional capacity to fix its own pipelines: the state is essentially an “incompetent North Korea,” isolated from the international community, ruled by a totalitarian dynastic government spending vast sums on fantastical monuments, and reportedly having seen a shocking population decline from around 6.2 million to around 2.8 million people as its citizens flee en masse to Uzbekistan and Turkey. Not exactly the kind of environment that trains and retains highly-skilled engineers, which is why foreign engineers entering to start patching the leaks is such a big deal.

Sam - This is an excellent and timely overview of the chemistry and processes that make methane such an important pollutant to control. It’s good to remember that in climate change, the ‘short term’ effects will likely be the rest of some of our lives. A 30% reduction is a start, though there is no reason to feel satisfied once that goal is achieved. Thank you for the research and clarity!

Really good summary of a big problem coming from a small country. I wonder what caused that Darzana hell crater? A good screenwriter could make a scifi/horror movie script. Movie profits goinging to Turkmenistan methane mitigation efforts! 😉