Life with Lemurs: 2019 Madagascar Diaries #1

Republishing my blog posts from my time as a volunteer research assistant in Kianjavato, Madagascar, in mid-2019

Background: from late July through mid-October 2019, I worked as a volunteer research assistant for the Madagascar Biodiversity Partnership (MBP), based out of the Kianjavato Ahmanson Field Station (KAFS). KAFS is located near the village of Kianjavato, in the eastern rainforests of Madagascar. During this time, I worked to assist MBP’s studies of the critically endangered greater bamboo lemur (Prolemur simus), as well as teaching English classes and later assisting the community reforestation program.

I wrote a series of “from the field” blog posts describing my life and work there as it happened, from a first-person “you are there” perspective. I’m now republishing excerpts from these on Substack!

This post starts with my first day waking up at KAFS: July 28, 2019.

I awoke to a landscape of surpassing beauty. KAFS is only a stone’s throw from a road, and is accessible by car, but is entirely surrounded by forest (although much of it is secondary forest, formerly degraded agricultural land). Since I was a child, I had dreamed of living and working in a rainforest biome like this, and here I am now. For that first day, I had to keep mentally pinching myself to realize that my life had truly led me to this point, and that I was not just a six-year-old idly dreaming of the jungle.

The landscape was dominated by the majestic mountains in the distance: Vatovavy, Tsitola, and Sangasanga, rising like stone islands above the forest sea. When not in an elevated location, lush vegetation dominated every horizon: groves of bamboo like gargantuan grass clumps, voapaka trees, anga trees, and many, many others whose names I did not yet know.

My eye was especially drawn to the massive ravenala trees, with their strange, nearly conical shapes fanning out like peacocks’ tails from their base on the ground. The “traveller’s palm,” as it is known in English (for its store of water in the trunk) seemed like it belonged to another world, so different was it from the standard trunk-branches-leaves style of tree. My fellow volunteer, the knowledgeable and compassionate Evan, informed me that they were also ecologically vital. Not only were they some of the first trees to grow in recently degraded land, they offered vital resources to all three of the endangered lemur species studied at KAFS! Prolemur simus sip nectar from the giant spiky flowers, Varecia variegata sip the nectar and eat the fruit, and aye-ayes sip the nectar, eat the fruit, eat the seeds, and probe for insects in the bark. With all of this munificence, I subconsciously rather expected the ravenala to be rare. Yet they were as common as oaks or maples in New England: KAFS is full of them, and their beautiful arcs of giant leaves dotted the mountainsides, the distinctive shape visible even from miles away. (Pictured, two ravenala trees).

Flocks of chickens wandered freely: their ease in the rainforest environment seemed curious, until I remembered that the common barnyard chicken is a domesticated descendant of the red jungle fowl of the Southeast Asian forests. Tiny striped day geckos, green geckos with red stripes (pictured) sunbathed on the railings of the great staircase-boardwalk that led from the main section of KAFS (with the dining hall, main building, and tree nurseries) to the hillside tent sites. Strange birdcalls filled the air, and Soumaya spotted a pendulous nest hanging from a tree, the owner of which remains a mystery.

During the day, some of the previous cohort of volunteers “showed us the ropes.” Jonathan walked us out a ways into the forest, to a ridge with a beautiful view of the local hills, and told us about the local ecosystem, the species mix, and the reforestation efforts. Carol walked us through the daily routine, the rules, the showers, the bathrooms, and the other necessities of life. After lunch (meals at KAFS are as a rule rice and vegetables, both excellent), Fredo Tana gave us the orientation lecture. A most impressive Malagasy gentleman, Fredo bore ably the tremendous responsibilities of being director of KAFS. Under his personal purview-and his responsibility-were three Malagasy research teams (Prolemur simus, Varecia variegata, and Daubentonia madagascarensis, the aye-aye), a massive and growing reforestation effort of linked tree nurseries and planting days in the region, a “Conservation Credits” program rewarding local citizens for taking part in reforestation initiatives, and, of course, a constantly shifting cast of inexperienced Western interlopers offering what little research help they were capable of (that would be us, the volunteers). Fredo gave us the standard orientation lecture, detailing the standard daily schedule (up with the sun at 5:30 AM, and to bed just after it at 7:30 PM), responsibilities, and so on.

By the afternoon, having viewed all the local wonders and with no work assigned as of yet, I began to feel homesick, and was cheered by a Skype conversation with my family. Then, something occurred which was to focus my mind entirely on the present moment.

Sunday Evening-The Ordeal of “Anna”

One of the previous cohort of volunteers, “Anna” (not her real name) had begun to feel sick that afternoon. Hale and hearty in the morning, she had begun feeling nauseous by 3 PM, and by the evening had chosen to stay in her tent rather than join the group at dinner. When Fredo went up to check in on her, I volunteered to bring her a bottle of water. We found her in her tent in a greatly deteriorated condition. Anna had the most terrifyingly violent fever I had ever seen, to the extent that being near her was like being near a space heater. She wore five layers of clothing and still felt cold, and had vomited and expelled blood for the last hour before we arrived. She mumbled her symptoms in English, and I related it to Fredo in French (his English is excellent, but he wanted to ensure that our understanding of Anna’s condition was entirely accurate). Fredo instantly determined that we needed to seek medical attention. She could go no further by the time we had walked halfway down the staircase, and a Malagasy staff member (whose name, alas, I did not catch) carried her on his back the rest of the way to the car. As we encountered the other volunteers on the way to the car, their cries of welcome changed quickly to looks of concern. None of us had realized how quickly Anna’s sickness had progressed. After I ran to the main building to grab some ariary for the doctor, Fredo asked me to come with them to the clinic as a translator, and I of course accepted. As we hurdled along the road to the village, our headlights the only relief from the surrounding darkness, I wondered for a moment about the chain of events that had led me here. I was a teenager from Maine who liked to watch birds and insects and learn about the woods. Now, I was the emergency translator for what seemed, in my inexperienced eyes, like a life-threatening situation, with one of our volunteers stricken by some unknown tropical ague. What was I doing here?

Despite her fever (or perhaps because of it, to some extent) Anna seemed far less worried than I throughout this whole process, pointing out village landmarks as we drove by. Once we reached the clinic (clearly a vital community center, staffed by white-capped nurses and with posters about pregnancy dangers on the walls), she told me all about her favorite lemur, Ghost, a Prolemur simus female with a color mutation that gave her a white ventral region. (She also asked if she had a fever, which made me wonder if she was a little delirious). And yes, she did say “ventral region” when lying on a sickbed in the clinic. Once a scientist, always a scientist.

Fredo translated the nurses’ questions (posed in quick-fire Malagasy) for me, and I asked them of Anna, returning the answers in French to Fredo. By and by, Anna’s malaria test came back negative, and she was given a shot of antibiotics and fluids by the capable nurses of the clinic. By the time we returned to camp, her fever had broken, and she felt hot instead of cold. Amazingly, by the evening of the next day (after a day of rest and another shot at the clinic) Anna appeared to have made a full recovery, and gaily showed the group her collection of local seeds at dinner.

We still don’t know what Anna had contracted (perhaps some local pathogen from impure food or water bought during a visit to town) but she’s fine now. Frightening though the experience had been for an inexperienced foreigner like myself, she was likely never in any real danger: I later learned that seemingly random bouts of illness are not unknown here, and generally resolved quickly by a visit to the clinic. Fredo and the Malagasy staff members had stayed completely cool-headed throughout, managing the problem with their usual consummate competence and efficiency. Once we returned to the camp that night, I told them all “Misaotra betsaka ianareo,” (Thank you all very much) and meant it deeply.

Monday: Meeting the Mayor, Entering Data, and the First English Class

The 29th dawned, and with it a new suite of surprises. The new volunteers (Dakota, Dana, Soumaya, Claire, and myself) walked into Kianjavato village with Fredo. Lychee, banana, and coconut trees grew in little plots by the side of the road, along with the omnipresent Malagasy rice paddies. Everywhere we went, small children greeted us with “Salut, vazaha” (Hello, foreigner) and Fredo introduced us to local citizens who worked with MBP in some capacity. There were so many of these latter (a good sign that the community was involved in conservation work!) that I was swamped by all the new names after a while. I responded to all with a polite “Faly mahalala anao” (Pleased to meet you).

We presented ourselves as new volunteers to the mayor, and I was amused and gratified to see that the Kianjavato Commune’s coat of arms featured the mountain of Vatovavy (literally “Woman Rock,” after a perceived similarity to a female face) on a field of blue, halved with an aye-aye’s head on a field of green. This pleasingly ecological insignia dominated the sign before the mayor’s office. The mayor himself, a kind and mustachioed man, asked us for our names and thanked us for our visit (in French). The forests of the Kianjavato Commune are not protected areas: they are communal forests, the equivalent of town land in the United States. Thus, all conservation work conducted by MBP in this area is entirely dependent on the cooperation and generosity of the local community. We next visited the secretary of the “FOFIFA” coffee plantation (an establishment which kindly allows MBP volunteers to research the lemurs established in their hinterland) and introduced ourselves there.

After lunch, I began my training for the Prolemur simus (greater bamboo lemur) research team. (For the first five weeks, I am to work with the Prolemur simus team, and for the last five, the reforestation team). Meeting the mayor had meant that I could not join the early morning field excursion, when the lemurs were most active, so I began by entering that day’s behavioral and social data into a KAFS laptop’s Excel sheet. This was an exhilarating experience: I couldn’t believe I was entering data about a critically endangered lemur species!

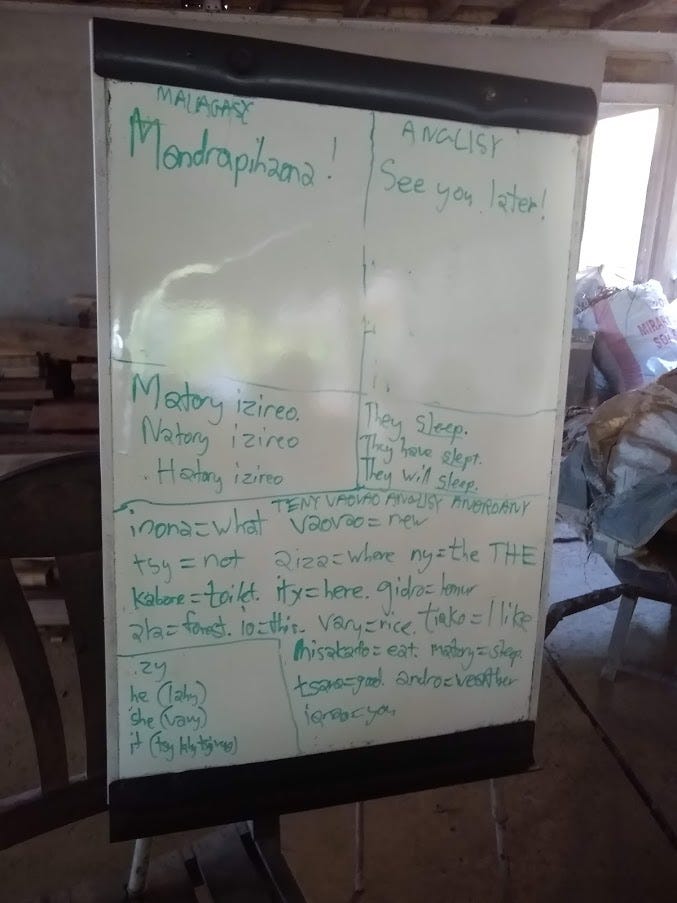

Shortly after that, a serendipitous occurrence added a new dimension to my stay. As Jonathan was still occupied by running over the Varecia data with the volunteers assigned to that team, he asked me to cover for him for his weekly English lessons, in which he instructed three or four of the staff. Though without any lesson plan, I have always loved the English language, and I knew a fair amount of Malagasy by then, so I was raring to go. With the aid of a whiteboard (Pictured: the whiteboard I used.) I discussed how in Malagasy, the pronoun is always at the end of the sentence (as in “Amerikana aho,” or “I am American”), whereas in English, the pronoun is always at the beginning of the sentence. I also touched on the forms of the verb “to be,” such as “am,” and “are,” which are necessary in English sentences, though absent entirely from the Malagasy language. Finally, I ran through English numbers, writing out the digits, then the Malagasy names, then the English names. By the time we got to higher numbers, more Malagasy staff members were listening in, and they had all got the hang of the basic “building blocks.” I started simply writing out complex numbers like “538” or “1732” and asked them what it was in English, and they responded correctly by putting together the English number names they had just learned. By this point, the atmosphere was positively festive, with group clapping and cheering, in which I joined, for every correct answer. I thought the lesson went very well, but I only learned how well at dinner that night. Fredo said that word of the English teacher who could speak some Malagasy had spread, that the groundskeepers were asking for English lessons for the first time, and that if I would hold another lesson next week, about twenty would attend! I of course accepted gratefully, and look forward with pleasing anticipation to continuing to share the English tongue with KAFS’ amazing staff.

Tuesday: My First Wild Lemur

Tuesday was a day I had been looking forward to for a while: my first day of field work! As usual, we rose at 5:30 and breakfasted at 6, but this time I piled into the van with Evan, the previous cohort’s Prolemur simus volunteer, at 6:30. As we drove, we picked up the members of the field team from the side of the road, and soon MBP’s van grew as crowded as a school bus. That day, our task was to search for signs of Prolemur activity in the foothills of Vatovavy, and the team consisted of Evan, myself, Olivia, a Malagasy graduate student, and three long-standing Malagasy guides, Hery, Marolahy, and Berthin.

We walked through scrubby, secondary forest areas with amazing views of the local mountains (pictured, above) and soon reached the real rainforest, full of woody vines, trees with massive buttresses of roots and thickets of adventitious roots, and a plethora of insect life on the forest floor. I was practically beside myself with excitement. This was my first hike through a rainforest, an experience I had dreamt of for years, and the most curious thing about it was that it felt perfectly natural. I had read so much about rainforests in general, and those of Madagascar in particular, that it seemed as though I was following a well-worn path in my mind-though of course with incredible additional excitement and stimulation. We saw no Prolemur simus that day, though we did log and geolocate several scats (nearly all plant fibers, astonishingly dry due to their folivorous diet). Amusingly, we were searching in particular for “Tyrion’s group.” Other Prolemur simus monitored by MBP also bear Westeros-inspired lemur names, such as Olenna, Brienne, and Snow.

However, we did see some other representatives of Madagascar’s incredible faunal diversity. We noted bright red millipedes, the green-headed and sweet-singing Madagascar sunbird, and, most amazingly of all, the first wild lemurs I had ever seen. Four individuals of Eulemur rufifrons, the red-fronted lemur, gamboled in a tree above usI knew intellectually that they were wild animals, adults of a species of social, vocal, frugivorous, lemuroid strepsirrhine primates, one of nine catalogued lemur species in the immediate Kianjavato area. Emotionally, though, they seemed like children’s stuffed animals brought to life: words like “plush,” “fluffy,” and “huggable” sprang to mind. (Disclaimer: the capture of lemurs for the pet trade is an increasing problem in Madagascar and a threat to many species, so please do not take from this the idea that it is in any way desirable to view lemurs as pets or tame animals). I will always remember this experience (these words were written later that very Thursday, the 30th [of July 2019]) and I cannot wait to get back out in the field tomorrow!

Wednesday and Thursday: Settling In to the Kianjavato Routine

On the 31st of July and 1st of August (the day I write these words), I feel I have begun to settle in to the routine of life and work at Kianjavato. The 31st was World Ranger Day, and all volunteers, regardless of their main teams, joined community members volunteering for the day in planting seedlings (from the network of MBP nurseries in the region) on bare or scrubby hillsides. At the site in which I took part (pictured below), I was astonished by the speed and smoothness of the operation, and the considerable experience and dexterity of the local volunteers. Malagasy seniors, mothers with babies on their backs, and children planted five or so seedlings in the time it took me to plant one, and the day’s planting was done with astonishing swiftness: over three thousand seedlings planted in a few hours! In the afternoon, I read, relaxed, and taught another small English class. I still can’t wait for my “formal” English teaching to begin next week!

That night, Evan pointed out to me a giant orbweaver spider and two vespertilionid bats he had noticed in the rafters of our tent site (a sort of giant wooden roof on stilts). He said he had named them Clyde and Colin and Joel respectively. I feel profoundly at ease in a group of people of the sort who, when viewing insects and bats in the roof of their living space, feel an impulse to name rather than destroy them.

This morning, August 1st [2019], I was with the Prolemur simus team in the field again. Hiking in the rainforests of Madagascar remains a mind-boggling bouquet of wonders. We again did not see any simus, but we did find an array of recent scats and a multiplicity of other species. (Details of data I work with for MBP are intentionally kept vague. As another point, I have not included any images of any of the lemurs I saw, as I have not been able to check if this is OK with MBP’s head office. MBP skillfully navigates an array of data and image reporting requirements between American and Malagasy partners, and I don’t want to upset the apple-cart by posting possibly unauthorized lemur photos). We saw two lemur species: the Eulemur rufifrons I had earlier seen on Tuesday, and two beautiful Varecia variegata, another of MBP’s study animals and another critically endangered species. We also saw many more tree species (including plethoras of ravenala, as well as bonary mena, anga, and other rainforest titans). Hery also pointed out to us a white-headed vanga, one of the many endemic bird families of Madagascar. After returning to KAFS and entering data, I finished up and sent this blog post, which I’ve been working for the last few days.

Though I miss my family greatly, and look forward to returning, I am beginning to feel at home here in Madagascar. It is almost surreal to realize that for the next three months, I will be gathering data on critically endangered primates and assisting with efforts to restore their habitat. This is an amazing place to be, and I am very happy to be here at this time in my life.

This week, I have had the inexpressible honor to work with habituated Prolemur simus groups, and look forward to gaining as deep an understanding as possible of these incredible creatures.

Friday Morning and Afternoon

During the course of the day’s work for August 2nd, several events of import occurred with regards to the Prolemur simus population in the Kianjavato area, some of which I may not write about. I may, however, say that Friday morning, after our usual morning of monitoring, I caught my first glimpse of P. simus, just a quick glance through the treetops at Tyrion’s group moving among the branches. The greater bamboo lemurs seemed to me, in that brief encounter, like brown pandas crossed with Spider-Man. They moved with jumps of incredible speed and duration, hopping between trees and bamboo-stalks like the Marvel wall-crawler between skyscrapers. Next week, we will be monitoring some more habituated groups of bamboo lemurs, and I look forward to gaining a better knowledge of these enchanting creatures.

Seeing the Aye-Aye

On the afternoon of the 2nd, I felt a hankering to test myself, to go the extra mile, to immerse myself further in the vibrant tapestry of Madagascar. When I learned that a Malagasy research team would be conducting a routine check-in on the aye-aye resident at Sangasanga Mountain that night, I asked for and received permission to be “seconded” to their group for the evening. I am intensely glad that I did, for it became one of the most stimulating and fulfilling experiences of my life to date. I became acquainted first with the guides: “Dada,” Dagah, Frederic, Sylvestre, and one or two others whose names I had not recognized clearly enough to hazard a guess at spelling them. Before we ascended the mountain, they were kind enough to let me use the ATS radio-tracking system and antenna, and I felt great joy at hearing the low, repeated beeps that indicated that a collared aye-aye was present in the direction where I had pointed the antenna.

Climbing Sangasanga in quest of the aye-aye’s signal was a process fraught with interest, especially once the Stygian darkness of the tropics had fallen (at about 5:40) and our only light came from our headlamps. The trail up was extraordinarily steep, to an extent that it felt to me more like rock-climbing than ordinary hiking, only with branches, vines, roots, and the great stalks of ravenala leaves as holds in place of stones. Whenever it became necessary to go downhill for a moment, that was generally so steep that the only safe method of travel was to slide downhill in a sort of squatting position, and trust to the next tree to arrest one’s progress. This was made more difficult by the fact that some of the trees and vines were covered in tiny spikes, and so were sub-optimal holds. I soon learned to test new holds with one finger, gingerly, at first, and only grip them fully if they were spike-free. I may sum up the general effect of the experience by saying that one particularly long and steep trail was named, in Malagasy, “Spend Sweat,” and rarely have I encountered a more absolutely appropriate designation.

Once we reached the top of Spend Sweat and the terrain leveled out somewhat, becoming something more like mountain hiking as opposed to quadrupedal vine-climbing, we all paused a while for a break. Earlier, knowing that the guides were a thousand times more experienced with aye-aye tracking that I was and not wishing to be a parasite upon the expedition, I had packed two liter-bottles of water in my backpack. At this point, I asked the guides, “Mangetaheta ianareo?” (Are you all thirsty?) and said “Manana rano aho,” (I have water). They shared out the water among themselves gratefully, and after this began to call me “namana,” or “friend.” Given the abovementioned state of travel, this generally manifested itself in comments like “Tandremo, namana!” (Watch out, friend!) or “Moramora, namana” (Slowly-slowly, friend-a term implying that caution is warranted).

Eventually, after careful triangulation by the guides, we found the aye-aye. This collared individual was known to the research project as Emerald, and indeed was truly a precious living jewel. My first immediate point of comparison when seeing the Aye-Aye was that it looked like an immense black squirrel. (I was staring up into the treetops, and the aye-aye was moving along a branch quadrupedally, so I could get no sense of its famously unique and specialized hands, with their long middle digit used in percussive foraging for larvae). There are indeed some points of resemblance to the squirrel, notably in the fluffy tail, the arboreal motion, and the body shape (when the aye-aye is on all fours). However, the face quickly dispels that impression. It looked a bit like a shaved Rocket Raccoon crossed with a human, a triangular yet hairless and indisputably primate-like visage. The overall effect was of something strangely elfin, or friendly goblin-like, something that did not fit with the Western mind’s established categorization of animal life. It looked like one of the principal fauna of Wonderland, something that might have dropped in no questions asked at the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party or co-officiated with the Dodo a race for which all would win prizes. (I did not bring my phone on the night hike, so the aye-aye picture above is shared from Wikipedia).

All this word-picture is drawn from perhaps fifteen seconds of observation, illuminated by the beam of my and the guides’ headlamps, triangulated from its flashing eye-shine, of a creature perhaps forty feet above me. A moment’s Internet search reveals much clearer pictures of aye-ayes, images of the full body, videos of their behavior, media that give a much longer and clearer view of the animal, and in broad daylight too. I had seen many of these, and read Gerald Durrell’s excellent The Aye-Aye and I, and read research papers on aye-aye behavior, and had conversations with fellow volunteers about the aye-aye’s fascinating physiology. And yet I feel that fifteen seconds in a dark forest gave me a different sort of insight into the creature. I was privileged to see the aye-aye in the environment it evolved for, going about its nightly business, a prime motif of the rich tapestry of the rainforest.

After we had checked in on the aye-aye, we retraced our steps. Even amidst the mad self-propelled slip-n-slide ride that is the descent of Sangasanga at night, my friends the guides were keen-eyed enough to notice and point out to me several other fascinating examples of the rainforest’s nocturnal life-forms. We saw a Uroplatus, one of the extraordinary genius of geckos whose scales are a bark-like brownish gray and whose tails have evolved to exactly mimic a decaying leaf-a highly effective evolutionary adaptation for camouflage that has given them the common-name of leaf-tailed geckos. The one we saw was one a bush, and its tail really did look just like a partially decayed leaf, with the little leaf-veins and everything. I have just ascertained from the station reptile/amphibian guidebook that it was likely Uroplatus phantasticus-a fitting name for this improbable product of natural selection! We also saw a snake, of unknown genus, that the guides called lapata (I felt quite relieved to remember that there are no poisonous snakes in Madagascar) and a lovely little praying mantis on a leaf. When I say we, of course, I mean that one of the guides saw the creature, called it out, illuminated it with his headlamp, and, if I failed to see it even that, answered my hesitant question of “Aiza ny biby?” (Where is the animal?” by pointing directly to its head. Alone in that forest, I would have been blind to the biodiversity around me, seeing no more than the trees and bushes immediately in my path. If there is any justice, or if the efficient market hypothesis has any value, Kianjavato will one day become a coveted center of ecotourism, and these amazing men will be highly sought after and paid stupendous fees as the Virgils that guide touristic Dantes through the divine comedy of the Malagasy rainforest.

Once we left the mountain proper, we were back at Kianjavato’s main street in an astonishingly short space of time. It’s heartening to think that in Anthropocene Madagascar, a land of an expanding population and a cultural and economic dependence on subsistence agriculture, wild aye-ayes and communally managed rainforest exist within walking distance of the heart of a populous village. (And that village, according to a research paper I read on use of natural resources on the Kianjavato region, home to a few families who until recently hunted lemurs for food).

As we waited for the MBP car to convey us all back to our respective homes, I was aching, filthy, and incredibly happy, grinning like a maniac. Thinking already of how I wished to share this experience, I tried to recall a Malagasy phrase I had earlier attempted to memorize, with a view to conscientiously asking Malagasy citizens I met whether it was acceptable for me to mention them in my blog. Now, with my notebook handy, and having successfully made the statement on later occasions, I can state with confidence that what I meant to say was “Mety manao hanoratra momba ny ianareo aho?” or “May I write about you all?” What I actually said in that street, in an Anglo-Franco-Malagasy patois born of a mind drunk on aye-ayes and post-exertion endorphins, was, “Can I write-um, ecrire, hanoratra aho (I will write)-sur cela? About this? About ianareo (you all)?” Dagah considered it for a moment and then said “Yes, please do,” displaying astonishing powers of linguistic decoding. And so I have done so.

In the car, I craned my head to look for the tiny driver’s-side digital clock. So much had occurred in the space of a few short hours that I thought it must surely be late at night-perhaps 11 PM, far later than I had ever stayed up in Madagascar. I laughed in amazement to realize that it was only 7:19! My aye-aye odyssey, which seemed to me to be about several days long, had taken about two hours and a half. When I returned to KAFS, my fellow volunteers were just finishing up their dinner.

Saturday and Sunday

KAFS volunteers have the weekends off, which are often spent in reading and catching up on data entry. I personally read a good deal. To my pleasant surprise, there is quite a considerable little library in the main building of the research station, composed of volumes left behind by a decade’s worth of previous volunteers. The selection is rich in works of science, science fiction, natural history, historical novels and books about travel in general and Madagascar in particular, which by a happy coincidence is just what I am interested in. Since I’ve been here, I’ve read Brave New World, Niven’s Footfall, Babylon’s Ark, Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven, and Master and Commander, as well as consulting several guidebooks more specific than my generalist Wildlife of Madagascar. I shall have to make some donation of my own when I leave, to “pay it forward,” though it will be a wretch leaving any behind.

On Sunday the 4th we all attended the Kianjavato town market, for it was market day. Evan showed all the new volunteers around the street food, which was quite interesting: I had cassava spheres, peanut brittle, a banana bread-like pastry, a sort of dough ball, and more. When you pay with something as large as a 5000 ariary bill (about $1.25) it positively holds up traffic, for the stallholder has to run around to other stallholders to collect enough cash to give you change. Most street food cost about 500 or 1000 ariary, or 12.5 or 25 cents. In addition to being amazingly cheap and as a rule quite good, I have at least one solid, glowing recommendation to any future travelers with American palates: the cassava bread. It’s fried, warm, and delicious, and tastes, to quote a fellow volunteer, exactly as if “cornbread and french fries had a baby.” On the way home, the volunteer party bought and shared two huge ripe jackfruits, which were eaten raw, in the style of the lemurs.

The 5th through the 9th of August-Getting to Know Prolemur simus.

The primate known variously as the greater bamboo lemur (English), le hapalemur grand (French) der Grosser Bambuslemur (German), Prolemur simus (Latin/scientific), and the varibolomavo (Malagasy) is a fascinating creature, with a storied history. Subfossil deposits indicate that it was once widespread across Madagascar-it is indeed the most abundant lemur in the subfossil record. It feeds primarily on bamboo, having evolved natural compensations against the high levels of deadly cyanide present in certain parts of that plant. As bamboo is an extremely quick-growing early successional species, the varibolomavo is well-adapted to Madagascar’s natural disturbance regime of droughts, fires, and cyclones. However, by the mid-twentieth century it was believed to be extinct due to clearing of forests for farmland and over-hunting. A sighting in the 1960s set hope alight again, and a series of expeditions in the 1980s (chronicled by one who was there in Dr. Patricia Wright’s For the Love of Lemurs) found surviving populations at Ranomafana and Kianjavato. Dr. Edward Louis has researched the genetics of the Kianjavato population, directly or indirectly, for much of the 21st century. The outgrowth of that research, the Madagascar Biodiversity Partnership, has been collecting data on P. simus from 2009 through the day I write these words.

Though the Kianjavato population is stable, if small (approximately 45-50 individuals from what I can gather: total population counts are inherently somewhat inexact and fluctuating, as individual lemurs may not be seen for months or years at a time), the species as a whole remains Critically Endangered. There are certainly less than five hundred, perhaps less than three hundred individuals left on Earth-indeed, left in the universe. In the last few years, the IUCN has listed them as one of the 25 most endangered primates in the world. MBP’s work, both at Kianjavato and with the further-north Torotorofotsy population, essentially constitutes humanity’s efforts to prevent this species from being driven to an untimely mass grave.

Prolemur simus is a cathemeral creature, most active in the morning and evening, and is normally very shy of human observers. The scientific literature warns that generally its existence can only be deduced from fecal traces and interviews with locals who have seen it some time ago. In Kianjavato, I am extremely lucky to be coming in after fifteen-odd years of habituating the local lemur groups, particularly those around Sangasanga Mountain, to human presence. This enables current MBP volunteer research assistants, such as myself, to collect data on the lemurs’ behavior from an astonishingly close vantage point.

On the 5th, 8th, and 9th [of August 2019] (I was confined to camp with a nasty cold on the 6th and 7th), I went out to Sangasanga to collect data on P. simus’ behavior in the wild there, and began the process of getting to know this social, intelligent, and vivacious little primate. I had been on the P. simus team since I arrived at KAFS, but until the 5th had seen no more of them than feces, data to be entered, and a brief glimpse of Tyrion’s group in distant treetops. Fascinating though all of those close encounters were, they paled in comparison to days with the habituated-dare I say friendly?-Sangasanga groups.

On the morning of each of the three days I have worked at Sangasanga so far, we were in the field by 7:00. The home range of many of the Sangasanga P. simus groups overlaps with land administered by the FOFIFA coffee plantation, which kindly lets MBP volunteers do research on their land. The Prolemur simus Malagasy research team-Theoluc, Hery, Mamy, Rasolo, Marolahy, Berthin, and Delphin-have worked with these animals for years, working with a multitude of volunteers in succession, and know them intimately. They are all dab hands at tracking the lemurs, by sight as much as by collar and radio antenna. Thanks to the skills of whichever of their number we were accompanying that day, finding the Sangasanga groups was never a problem. As quickly as ten or fifteen minutes after walking off the streets of Kianjavato through the FOFIFA gate, we were surrounded by bamboo and ravenala alive with lemurs.

There then followed, each day, six hours of Elysian delight, of complete immersion in the world of another species, of unparalleled access to the life of the greater bamboo lemur. For that time period, we took data on one individual’s behavior every five minutes (our “follow individual” for that day) and noted other lemurs present and certain particularly noteworthy behaviors of the others. On the 5th, “Lando” (after Lando Calrissian of Star Wars) was our follow individual, a radio-collared male. On the 8th it was “Luna,” (after Luna Lovegood of Harry Potter) a female with a young child, and on the 9th “Juno,” (after the Roman goddess). For Lando, we logged behaviors including sipping nectar from a spiky ravenala flower, chasing other members of his group through the canopy with an astonishingly cacophonous noise, and simply resting on a branch or the stalk of a ravenala leaf. Luna and Juno also rested and drank from ravenala flowers (Juno especially seemed to love the sweet nectar!) but they also spent time grooming their babies. Everyone, of course, invested considerable time in eating bamboo (pictured, above) feeding on the stalk, the apex, and the leaves. The group’s babies are nearly juveniles now, and semi-independent. It’s also quite likely that Luna and Juno are currently pregnant, as varibolomavo can nurse and gestate concurrently, and most babies are born in late September, only a month away. (Although, a warning in advance: I shall not be able to write of any specific births, for that is critical information that must be disbursed through the proper channels by MBP only).

As Prolemur simus are social primates (and, incidentally, one of only two lemur species to have a patriarchal social structure: the others are nonsocial or matriarchal), we were generally able to see most of a group while logging data on the follow individual. On each of the three days I’ve been on the varibolomavo trail so far, there came a certain magical moment where you realized that the group was no longer in any one direction, but all around you. You had, in fact, been surrounded and encompassed by the group, and were now among them, with lemurs in the understory on all sides. This often occurred in rich feeding grounds such as bamboo groves, and this period was generally the time when the lemurs got the closest to you. The picture to the right [below] was taken at this time on the 8th, and depicts Luna’s young, curious child investigating the strange bipedal hairless giant ground lemurs that so regularly intrude upon his domain.

Interestingly, in addition to being a winsome description of humans from a lemur’s perspective, this appellation holds a grain of truth. In an evolutionary sense, humans are essentially bipedal hairless giant ground lemurs, our distinct size, bipedality, terrestrial status, and hairlessness all having evolved long after we shared a common ancestor with lemurs. That common ancestor, as a point of interest, likely lived in the Eocene era, fifty-odd million years ago, when the Earth was ice-free and rainforests bloomed around the Arctic Ocean (although a few experts put the point of divergence much earlier, before the extinction of the dinosaurs). It was possibly something quite like the fossil known as Hotharctos1, a sort of proto-lemur more similar to the lineage that would eventually evolve into a multiplicity of forms in the splendid isolation of Madagascar than to the apes and humans of today. Without delving too far into anthropomorphism, I may say that when looking into a varibolomavo’s eyes, there is a recognizable spark of intelligence there, a twinkling reminder that this little life-form shares the order Primates with the creature that went to the moon.

Were it not for the Malagasy researchers, I personally would have had no hope of effectively tracking the greater bamboo lemurs’ movements, let alone identifying the follow individual. Experienced varibolomavo-trackers like Hery or Rasolo seemed to have the gift of leading us not to where to the lemurs were passing through just now, but where they were going to be in the next minute, and generally where they were going to settle down and feed for the next half hour. They then generally had to point out the individual we were tracking, and endure my craning head and questions of “Aiza ny Luna?” (or Lando, or Juno), for the brown lemurs often seemed to blend neatly into the sun and shadow-dappled canopy. Once they pointed out the focal lemur’s new locale, though, I had no trouble staying tuned. Like one of those optical illusions in a child’s book of tricks, or the Waldo in Where’s Waldo, the presence and activities of the lemur amidst the phantasmagoria of flora were invisible to the inexperienced eye, but perfectly obvious and trackable once you had seen it the first time.

Prolemur simus (pictured) are very vocal, as well, chattering little fellows in the best primate tradition. Their calls are near-omnipresent during active hours, though not very loud. These range from a “brr-rrr-rrt” multipurpose call to an edgier “yark!” of emotion to a plaintive “yaarp” used by babies calling to their mothers. The noisiest part of the bamboo lemur experience, however, is not a vocalization but the sound of their movements. Shy they may be sans habituation, but these little guys are anything but stealthy. They jump long distances between bamboo stalks and ravenala trunks with no thought to the noise they make, and run through the canopy likewise, setting up a great crash and bustle of leaves, branches, and stalks when the group is on the move. To one used to the relatively retiring and quiet denizens of New England woodlands, the decibel level can be quite surprising. I personally suspect that this lack of diffidence and timidity is due to the local ecology. In the absence of cats, foxes, raccoons, bears, large mammal-eating snakes, or other such non-Malagasy partially arboreal predators, there is little that the varibolomavo have to fear in their natural state. Their major predators (and the major predators of most lemurs) include raptors, which can be avoided by withdrawing into the cover of the canopy, and the ground-dwelling fosa (an endemic euplerid carnivore), which can be escaped by climbing. Thus, in the mid-canopy and understory, the greater bamboo lemur seems to know that it is relatively safe, and can bounce through the world to its heart’s content, heedless of the clamor raised by its gambols.

Another point worthy of note in the ecology of the Kianjavato population of P. simus, especially relevant due to its broader implications, is their enthusiastic use of non-native species. The jackfruit tree (Artocarpus heterophyllus) introduced as a food crop to Madagascar, grows in feral abundance in the forests of Sangasanga. The fruit is appreciated greatly by the varibolomavo, and regularly consumed as a fructose-rich supplement to bamboo. Perhaps more surprising is the role of the (again introduced) soapbush, Clidemia hirta. A low, leafy, fast-spreading ground cover, the sort of plant generally derided as an invasive weed, it plays a small but critical role in the weaning of varibolomavo babies (which takes place in January), who transition from milk to bamboo via hirta’s little blue berries as an intermediate, more palatable solid food. In addition, the soapbush is much prized by the researchers, as an array of tiny yet stable hairs make the leaves perfect soft scrubbing-brushes for removing dirt and soothing itchy mosquito bites. It’s rather iniquitous that according to the conventions of conservation biology, these useful and harmless species, with great benefits for a critically endangered primate, are docketed as “invasive species.” Might we not reserve that emotionally and culturally loaded term, with its appeal to nationalism and implicit call for a rejection of the invader, for the tiny minority of truly harmful introduced species, like the cane toad in Australia or the brown tree snake in Guam? Indeed, I will use this platform to call for the adoption a new term to describe introduced species that provide valuable services to the ecosystem. Let us call the jackfruit and soapbush in Madagascar, and their ilk around the world, “immigrant species,” invoking their positive contributions.

Before concluding this account of my second week on the Prolemur simus team, it is past time to give special recognition to Theoluc Nasolonjanahary, that team’s leader. As Fredo leads KAFS overall, Theoluc leads the varibolomavo team, with years of experience working with them under his belt, and is a devoted and effective force for conservation of the species. Often, I really feel that the highest duty of the simus volunteer is to act on his plans and aid in his works as much as possible. The man has been working with the species for ages, watching volunteers come and go, and knows intimately every aspect of the program, from the specifications of the radio-collar receivers to the behavior of individual lemurs. The varibolomavo are lucky to have such a protector.

I nearly forgot to mention my first two “formal” English classes, taught from 3 to 4:30 on Monday and Wednesday! I feel they were great successes, although of course an immensity of work remains to bring my pupils up to basic conversational fluency. I really enjoy teaching English, I very much like my students, and the experience is also greatly improving my Malagasy. Pictured is my whiteboard at the conclusion of the Wednesday lesson, with a list of “Teny Vaovao Anglisy Androany” (Today’s New English Words) taking up most of the bottom half.

After the week’s work wrapped up, the May 2019 cohort of seven volunteers left for Antananarivo, and should be returning to the homes in the US, Canada, and Europe next week. This also marks one-quarter of my time in Madagascar: three of my twelve weeks have elapsed. For the next six weeks, the only outlanders living at KAFS will be the July 2019 cohort (Soumaya, Dana, Dakota, Claire, and myself) and the longer-term graduate student researchers (Li-Dunn, Devin, and Pamela from abroad, as well as Malagasy graduate students Patricia, Olivia, and Faranky). After that, for my last three weeks, the September 2019 cohort will be settling in, and we will be “settling out.”

Back to the present, the sudden reduction makes the place seem a little emptier. I shall particularly miss Evan and Kate, the previous Prolemur simus volunteers, who trained me in the ways of the program. For the next three weeks, until I hand Prolemur over to Claire and join the reforestation team, I will be the sole research assistant for the premiere field team studying one of the world’s most critically endangered primates. (Pictured: myself with a P. simus in a ravenala above me). I will bear responsibility, along with Theoluc, for the budget, the biweekly reports, the proper handling of field data-in short, the whole kit and caboodle. It’s a little intimidating, in the sense that I am determined to ensure that all duties are conducted as well as they possibly can be. However, my overriding emotion is one of great joy-this kind of work is what I have dreamt of since childhood, and the prospect of witnessing the life of the varibolomavo for weeks on end is a signal pleasure, honor, and privilege. I am truly happy here in Madagascar, and I am inexpressibly grateful for all the support I have received that enables my sojourn here.

I wrote Hotharctos at the time, but I was thinking of Notharctus.

"Like" is an inadequate term to describe my reaction! "Wonderful" comes to mind! Great writing- collected under one cover- would make a great book!