Interview: Dr. Jill Pruetz, Fongoli Chimpanzee Researcher

The spear-wielding, cave-sheltering, fire-savvy savanna chimps of Senegal.

Dr. Jill Pruetz is the Professor of Anthropology and Honorary Professor of International Studies at Texas State University. Since 2001, she has led the Fongoli Savanna Chimpanzee Project, studying an extraordinary group of great apes on the savannas of Senegal.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Dr. Pruetz’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

Could you tell me how you got to the point of leading the Fongoli Savanna Chimpanzee Project?

Well, before I even went to graduate school, I worked with captive chimpanzees and I really fell in love with chimps. Ruined me for any other study species! I didn't actually study chimps until I was a postdoc, but as a graduate student, I studied monkeys in Kenya in a savanna. I really love that type of habitat, I'm interested in ecology, and so I decided what I would do was study chimps in a savanna. No one had really done it.

It took us four years to habituate the chimps to human presence, but we were successful. I chose Senegal because there had been a project there in the 1970s studying primates. That area is the northwestern edge of the chimpanzees’ range in Africa, the limit of where they can exist as a species. That project closed because they didn’t habituate the chimps - it takes a long time to habituate apes to human observer presence. I thought it would take longer than four years, but it did take us about four years.

When I started the Fongoli project, I went out as a postdoc in the year 2000 to do surveys of chimps in Senegal. The Fongoli site had a very high density of night nests that chimps build to sleep in. I started my project there in 2001. And one of the things that was really intriguing about Fongoli, and southeastern Senegal in general, was that most of the chimpanzees live outside of the national park area. So most chimps that are still found in Senegal live alongside people. People are just part of their lives. And they have been for, you know, millennia. As an anthropologist, that was very intriguing to me.

So even before the chimps were habituated, we were able to do a number of ethno-primatological studies, bringing in the human side of things. And in fact, chimps are one of the few large mammals left in the Fongoli area, because of cultural taboos that protect them from being hunted!

At any rate, that was a long story, it was kind of a winding path to get to Senegal, but yeah, that's it.

That is spectacular!

So this specific group of chimpanzees, they've been doing so many different unusual behaviors. The first one I wanted to ask about is their increasing nocturnal activity. Do you think that's due to climate change? Do you think it’s due to the increased heat in that landscape? Can you tell me more about that? And then I have more questions about their tool-assisted hunting and arboreal nesting and navigation of the fire landscape and a bunch of the other stuff from your papers that I've read.

I spent a little over 40 nights out with the chimps to record their nocturnal behavior, because we had noticed that they would move during the night, significant distances. We arrived to study the chimps before it gets light, we get to where we left them in their night nests, then basically we’re arriving before dawn and finding that chimps had been moving over a kilometer. So that's why we started paying attention to their movement at night, because it wasn't something that was thought to be common for diurnal primates in general.

It is associated with heat stress, and I can’t say that it’s a recent behavioral change due to climate change, but I imagine that climate change will only exacerbate the fact that the chimps need to be active at night. It’s basically a strategy to stay out of the hottest time of the day. This occurs during the dry season, and the dry season temperatures in Senegal are extreme. Water is the scarcest resource. Being active at night does expose you to predators, though, and at Fongoli there are still chimp predators there. Leopards, rock hyenas, spotted pythons. Some others are no longer there, like wild dogs and lions. I do imagine that climate change will probably just increase the amount of time they need to be active at night.

One of the things that I've said, I don't think I've published this yet, is basically that they're at the limit of what some call the temporal niche. In order to survive, they need to be active at night, which we as humans don’t really expect from a diurnal primate. We just kind of think that they'll sleep through the night.

Fascinating. So these chimpanzees at Fongoli are also innovators in several other ways, right? Like, they’re doing tool-assisted hunting in a way that's potentially very similar to early human ancestors. Can you tell me more about their hunting and tool making and how they use tools?

Yeah, so that’s probably the most exciting finding, I guess, to come out of the site. When I set out to study savanna chimps, basically my goal was to understand how they differ from chimps in more forested habitats, wetter habitats, and to really understand how the environment influences a great ape. In part because I think it’s informative for understanding early hominins. Early on, about five years after the project started, one of my project managers, Dr. Paco Bertolani, had seen chimpanzees stabbing branches that they had modified into hollows in trees. We chatted about it, we weren't sure why they were doing that.

Then he observed Tumbo, who is now the alpha female of the group, obtain a bushbaby using these stabbing, jabbing modified branches. It's something that's been regular, it's a seasonal behavior. One thing that's especially interesting now is we're actually seeing a decline. I think we’re going to focus on this over the next few years, but there seems to be a trend towards declining hunting behavior. I think that’s because you have increased human presence in the area, because of an ongoing gold rush that started around 2008 or so. The human population in the nearby town has increased, a lot of the biggest trees in the area have been cut down for lumber, and those particular trees, Pterocarpus erinaceus, are the ones the bushbabies nest in, these hollow trees and branches of that specific species. So I think it may be why we're seeing a decline in bush baby hunting. I think perhaps the bush baby population has decreased, but that's something we need to look at. That’s a behavior that could be lost due to these anthropogenic pressures.

Interesting. So these hunting sticks, did the chimps sharpen them into points with their nails, their teeth? How close is this to a whittled spear?

They're very systematic in their tool use. They almost always break off a living branch. They're particular about what types of trees they use. So if they're going to hunt, they find a cavity that's promising in a particular tree species. And if it's not the species that they prefer making hunting tools from, they'll leave that species and go find this other species, which is also very common. They usually don't have to go far. They find the Terminalia species, break off a living branch, and then return.

What they do is, they break off all the side branches. The tools themselves are usually about 70 centimeters on average in length. They break off all the side branches, and then they break off the terminal end, the skinniest end, and they break that off. Some of them do use their teeth to further modify that tip, which I tried to call “sharpening” in one paper, but I had to replace that. They modify the tip of the tool with their teeth.

Some individuals actually go as far as removing all of the bark off the tool, which I personally thought was a little bit overkill, until I had some film people ask me to exhibit the behavior for them. Removing all the bark on the tool actually reduces friction quite a bit! Because these cavities where the bush babies nest are not like a pipe, a smooth hole in the tree or branch, there's a lot of little protuberances and different things like that. Removing all the bark does help you jab in the tool more forcefully.

Yeah, it just depends. There are certain individuals that exhibit that behavior almost always. Like Tumbo, the alpha female, will almost always remove the bark from the tools that she makes.

Wow.

Another really interesting paper you wrote was about the chimps’ seasonal stress. This relates to what you talked about with them living at the edge of their niche. So your team collected urine samples to see their cortisol levels and stuff. Can you talk about that seasonal stress model that you and your team discovered?

Well, behaviorally, there were a number of different types of evidence that we recorded that suggested they're very seasonally stressed. For someone coming from the U.S. and being out there studying chimps, the heat is like a slap in the face sometimes. It seemed, hypothetically, that it would be hard to imagine that they wouldn’t be stressed. But of course, you know, the chimps have lived there. They may be adapted to that type of environment. Still, there were behaviors that we saw, like nocturnal behavior, soaking in water, a number of behaviors suggested that they were heat stressed.

Dr. Erin Wessling collected urine samples as well as behavioral data and found that they were in fact stressed. Water stress, that's always been the resource that we've suggested is the most limiting. Again, based on behavioral observations and how far they go for water, how very few water sources are in the area. And then she was able to demonstrate that biologically, yes, they they are indeed stressed.

There are pressures since I started the project that stress them out further. Access to one of their traditional water sources is limited because of a gold mine in the area. And these are artisanal mines, they’re small mines, so a chimp can actually get in there if it's a day where people are not there. And there's specific days that people don't work in the mines, on Fridays, for example. The chimps have that schedule down, and they’ll go back and drink. On other days, though, if they're in the area, it's usually only adult males can sneak in there quickly and take a drink before they're discovered, and they don't like to be discovered by unfamiliar people. So, you know, there are behavioral indices, and I think they could ultimately get worse or be exacerbated by climate change.

Fascinating.

You’ve written about the Fongoli chimps’ arboreal nesting (an anti-predator adaptation?) and cave use (an anti-heat adaptation?) So there are caves in this area, and they're using them, and they're also doing arboreal nesting. Can you tell me more about the structures that they use to sleep in?

Cave use was one of the first things that we wrote about, in fact. When I first started at Fongoli, my head guide and field researcher, Mbouly Camara, who has since passed away, he grew up in the area, he knew about some chimpanzee behavior indirectly or from glimpses that he saw. One of the first things he told me was that the chimps use these small caves. I was like, oh my god, that sounds amazing. Again, as an anthropologist, yeah, I'm thinking back to cave use among earlier hominins.

We did put camera traps in the caves. The chimps seemed to be averse to them in the beginning. I ended up using traces of knuckle prints, foot prints, shed hairs, and food remains in the caves to monitor their cave use. It’s something that they do during the dry season, so another thing I did was put remote temperate loggers in different habitats, and the caves are a cool area. The temperature is almost the same throughout the year.

These are actually rock shelters, the cave folks wouldn’t call them complete caves because you don’t get complete darkness where the chimps are. But they do remain cooler. You'll actually see competition over access to the caves. The adult males and some of the adult females will get priority of access to the resting in the caves during the heat of the day.

I published a paper with a former Ph.D. student of mine, Kelly Boyer Ontol, who studied a chimp community further north, in an even drier area of Senegal. She used camera traps because the chimps were not habituated. And there was a larger cave there. What we found was that lactating females were more likely to use the caves than any other age/sex class, besides their dependent offspring. Which makes sense, because that is a very stressful time for females.

So, for example, if we're looking for chimps in the dry season, you don’t want to lose them because then you have to walk for hours and hours. But they have a very

big home range 100 square kilometers or so. One of the things we'll do is, we’ll go to these caves. We’ll hit up water sources to try to find the chimps, and then we'll hit caves as well, and you may find females in particular hanging out at certain caves.

Fascinating. This is a savanna landscape, so these caves, are they, like, in isolated rock formations, kind of like in the American West? And then the nests are going to be in trees? Do they use nests to sleep in and caves to shelter in during the day?

The caves are all associated with these, what we call ravines. It's an area that's been um in the landscape that's usually also associated with tiny patches of gallery forest. About less than three percent of the home range at Fongoli is gallery forest, but that is

a crucial habitat because it’s where the water sources are. Over, you know, eons, water action has produced these ravines that have gallery forest in them, and that's where the caves are as well. They're also a place where the chimps regularly nest.

One of our favorite places is one of these ravines, in part because it's only a kilometer from camp. So we don't have to get up at 3:30 AM and leave, but we get to sleep until 4:30 or something. The chimps use a cave there frequently, and there's a rock pool that has been carved out because of water action over the eons as well. When the rainy season starts, they soak in that pool until it cools down.

So these are areas that are selectively used. That, to me, is interesting. I wouldn’t call it a home base type of situation like you'd get with earlier hominins, but it is definitely something that they radiate out from during the dry season. The ranging pattern is maybe different from what you see in forests, where you’re focused on feeding more than water use. I’m interested in seeing that. We've got tons of data, but we haven't published on that yet. So I'm waiting for an enterprising student to wrangle all my years and years of ranging data, perhaps.

This is absolutely fascinating. So, one other topic that you've researched is inter-chimp aggression. This is a tense landscape, water scarcity, living on the edge.

Obviously, there was the most famous example of documented chimp

aggression, the Gombe Chimpanzee War between the Kasakela group and the other one. Do you see aggression that would rise to what you would describe as a war? Or a

skirmish, or more sort of interpersonal? What sort of conflicts have you observed over resources, over status?

We haven’t seen a lot of inter-community aggression because these chimps have such large home ranges. Jon Mitani published a paper with a formula that allows you to predict when boundary patrolling would be beneficial. The boundary area at Fongoli is too large for frequent patrolling to be beneficial. So we don't really see that. What we do see sometimes is incursions into the other group's range. The one neighboring group that we're aware of, where we've done a little bit of indirect study over the years, is smaller.

How many chimpanzees are in each group, roughly?

At Fongoli, roughly 32 on average over the past 10 to 15 years. Right now we’re at 34 chimps. This neighboring group, the Bantan group, probably has only about 20 chimps, just based on our studies of nesting and collecting fecal samples for analysis from that group. We do run into them every once in a while, but it's rare because they're not habituated.

So if we're with the Fongoli chimps when they're going into the Bantan community's home range, and they end up coming close to one another, then we kind of win that battle, because, you know, they're not habituated to humans. They're very frightened of us. There are times though, when we're kind of lagging behind, there may be some sort of scuffle.

But what we have seen is that there has been at least one, almost certainly an intra-community killing of a former alpha male. We didn't observe it, but we heard it and everything points to the interpretation that this former alpha male was killed by males in the group. What had happened was he was kind of ostracized from the group, probably five years previous. We had actually thought he had died, because there's a lot of males in the Fongoli group, usually 10 to 12. The sex ratio is pretty skewed, there's a lot of male-male competition, and the main resource is females, and status.

So this male was gone for over a year. We thought he had died. And then he tried to come back into the community after a couple years, as a higher-ranking male, with a couple of allies. But the other ape males were not having it. One night, we heard some sort of battle that sounded abnormal. We've heard it so many nights, you can tell when they’re in their nests and pant-hooting and calling. And you can tell when they get out of their nests and move.

They had moved. The next morning, my head researcher, Michelle, found a dead chimp, Foudouko. I had malaria, but I went out and identified him because I knew him, and it was the former alpha.

Then there was another case where we had a former alpha, an alpha that was, ultimately died from wounds. That’s considered different than an outright killing. Chimps are considered to be one of the few species that will outright kill a member of their own species, if they have enough coalition partners to help them, usually a 5 to 1 ratio or something like that.

Yeah, so we’ve seen intra-community killing. There was another case where this other very aggressive alpha male was attacked concertedly by most of the males in the group, and he ended up dying 10 days later from wounds.

So we do see some events like that overall, though we don't see more aggression than in East African chimps, especially. There are are subspecies differences. We haven’t seen a lot of between-community aggression, but that makes sense just because of the ecology of the landscape.

Very human, in a way.

Something else that’s particularly evocative is their navigation of the fire landscape and prediction of wildfire behaviors. They seem to be becoming more comfortable with fire, learning how to manage its appearance in the landscape. Is that an accurate summary? You wrote that they can predict wildfire behaviors, and that just really fascinated me.

One of the things that you routinely see at Fongoli and much of southeastern Senegal is that there are wildfires that occur at the beginning of the dry season, usually. There are natural fires, but probably most of the fires that we see at Fongoli were set by

people to manage the landscape. Clearing land that they're going to plant the next growing season, for example. Or maybe hunters want a clear area, to use that as a hunting tactic.

Nowadays, since there are these artisanal gold mines, which consist of just big holes in the ground that are several meters deep and at least a meter across, they can be dangerous, you know, if you're walking in a very grassy landscape. Most of the understory at Fongoli is grass. Some of the grass gets so high it’s over a human’s head, makes for very difficult walking. If you're in the area of a gold mine, it can hide these pits. So what we see now is burning because of that.

But at any rate, it's something that's regular. At least 75% of the chimps' home range is burned every year. It's just a part of what goes on there. And the chimps are very good at predicting the behavior of the fire. I’ve been with them, a couple times, in the vicinity of fires that I were actually what I considered to be pretty dangerous fires.

One was a late dry season fire, which can be especially dangerous because you have a tinderbox in areas that haven’t burned yet. Those are the fires also that really hurt the vegetation. It is a fire-adapted landscape, most of the vegetation is adapted to fire, but those late dry season fires are the ones that stand out, what we think of as forest fires, very destructive. I was with the chimps a couple of times during these, and I wrote a short article just about how compared to me they were much better at predicting how the fire would move.

They also really seem to be conserving energy in terms of how they move just right ahead of the fire. It was during the hottest time of the year. It was during the hottest part of the day. And rather than just leave the area, which was along a dry stream bed where you could still find some shade, they would just move ahead of the fire, move ahead, groom, watch. A lot of the fires they deal with are not that extreme, but they still would worry me.

“Even the most intense fires are met with relative calm and seemingly calculated movement by apes in this arid, hot, and open environment….more than 75% of these apes’ home range may be burned annually.”

-Pruetz & Herzog, 2017

My protocol, and I tell students this - and students are also always with one of the researchers from Senegal as well - is that you need to follow the chimps! If you're in the vicinity of a fire, unless you're absolutely 100 percent sure you could leave the area, follow the chimps and do what they do. Because the fires can shift, the smoke can be a problem, it can be all around you. It's just really hard for us to navigate it, but the chimps do a really good job and don't seem very alarmed by fire at all.

This is incredible.

What are your thoughts on the long-term potential evolutionary future of savannah chimpanzees? This is maybe more science fictional, more speculative, but I have to ask. So what we have here is a group of chimpanzees that are, to an extent unusual for chimpanzees, sharpening sticks, using caves, existing in a savanna landscape as opposed to a forest landscape, and getting better at understanding fire on some level. That seems to add up to a very particular set of circumstances, right?

What do you think are the odds of some kind of 2001: A Space Odyssey moment someday where the Fongoli population crosses some kind of development boundary that we haven't before seen in chimps? Because here we have chimps really starting to understand fire. What if, hypothetically, a chimpanzee picks up a burning stick and then maybe a couple generations later pokes a bush baby with a burning stick and cooks meat? What potential amazing stuff could we see here in this site, given that there's all these really unusual things happening?

Well, I mean, that's exactly why I started studying the Fongoli chimps, because I was interested in the selective pressures that we think shaped hominin evolution. Until we habituated the Fongoli chimps, there hadn't been chimps studied in a savanna behaviorally. Now, there's a second community of chimps that are habituated in a savanna habitat in Tanzania.

So, yeah, all these different factors we had associated with early hominins. We can see how it might have occurred by observing great apes in a similar type of habitat. The scenarios just present themselves, over and over again.

One of the things that I had a postdoc, Dr. Nicole Herzog, look at, was whether they were seeking out burned foods. We had not seen much evidence of it over the years. She did a systematic study and didn't find very much evidence of them seeking out burned foods. But they did take advantage of burned areas for travel!

Maybe Westerners, or people that watch Bambi growing up, have this idea of how animals react to a wildfire. We have a lot of wildfires in North America right now, right? And it's just destructive. You need to get out. You can't, you know, navigate around these big wildfires. But it's a very different thing that we're seeing in Senegal. Not that they're not dangerous, but just to be in the vicinity of a fire gives you opportunities.

Like you were saying, what happens if they find something that's burned and put two and two together? I've kept an eye out for other uses of fire. In the late dry season, it's cool at night. It's like in the 60s Fahrenheit, which just feels very cold. And if there's a burning tree stump, if it's a dead tree or something, it may burn for days and days. I'll stand by it to keep warm. I've never seen the chimps do that. Granted, they have hair. But, you know, I always wonder, why wouldn't you just sit by the warm fire?

We've seen them play in ashes, ashes that have just cooled, kids especially. We've, you know, kept an eye out for things like that. She did find that they were using fires to navigate the landscape, which puts them in close proximity to burned areas. They maybe are even looking for burned areas. It makes sense from the perspective of a hominin that's walking in a landscape that is covered with grass, just navigating the environment, where visibility is very poor and you have big predators.

I feel these chimps potentially fill in some gaps as to how this might have first started. And fire is just….there’s a number of hypothetical situations that could be informed from what we see, with a great ape that lives in the savanna habitat. That was an impetus to study chimps in savanna, because we've studied savanna monkeys quite a bit, especially baboons, but we have not studied a great ape. The fact was, you know, the argument from homology. Studying a species that's more closely related to us, in an environment that we think is very similar to what some early hominins subsisted in. I think it just is interesting.

And water, you know, water has always been a resource that's considered to be very important. When you look at these chimps in Senegal, it's so key. Without these water sources, they couldn’t survive. They have to have these water sources that are external to what they get from fruits and things like that, in a savanna.

What are your thoughts on the future of this chimpanzee group in Senegal, and of your research? I know Senegal's political situation got a bit unsteady recently with the whole Ousmane Sonko controversy, but now there’s the new president Bassirou Diomaye Faye, and things seem to be going well. Does the climate seem like you can continue doing research? Does the new Senegalese government seem like broadly in favor of wildlife conservation? Does the community seem like they'll continue giving social license to operate for wildlife conservation in the area?

Senegal has always been a great place to work. Every once in a while there’ll be some sort of political issue, and this past year with the election was probably the most serious, but at the last minute, things turned out well. It seems like people are happy with the new president. I’m going to visit Senegal in November, so I’ll see for myself.

But nationally, one of the things threatening the chimp population is gold mining, both artisanal and corporate. Corporate level mines have to work through the government and are obligated to do environmental impact and offsets and things like that. Artisanal mining is not regulated as much and you have a lot of new people coming into the area. The local people have always been incredibly supportive, I could not have done a project without the people in the area, but you have people show up who might not have the same taboos against killing and eating chimps. Some of the people these gold mine areas are incredibly impoverished. That is a worry. It’s something we’ve been dealing with for some time now.

When I’m not there, I have a full Senegalese research team out studying the chimps, we try to study them at least 20 days per month if not more. Every day, there's an effort made to stay with some of the chimps in the community. That, I think, is

something that's important. I think it's important to monitor them, especially as you have all these changes.

But I am worried too, and primarily it's because of the water sources. I had a master's student, Mackenzie Miller, she's now studying mountain gorillas in Rwanda for her PhD, but for her master's, what she did was collect data on a lot of the different ecological variables. She used a thermal imaging camera to collect data on the heat that the chimps experience in certain habitats in real time. She also looked at chimpanzee biology using captive chimp data, and used a program called Niche Mapper, basically what it does is model climate change and how species can react. And according to Mackenzie's work, the chimps at Fongoli should be able to subsist through at least the year 2080.

I was surprised it was that long, but that’s based on an estimated increase in temperature. It’s not taking into account other anthropogenic changes that may occur, like them getting excluded from one of their water sources. But that's something that we're working with that we are very cognizant of, and something that we're prepared to deal with in terms of conflict between the chimps and people in the area. Like at these gold mines, that type of thing. I do think that it will be challenging in the future, way after I am gone. But, you know, I have a co-principal investigator of the Fongoli project, Dr. Landing Badji. He's an amazing person, amazing scientist, and he's also done a lot of work with the communities. He's Senegalese, he speaks like 10 languages. I am very confident that the project is in great hands with Landing.

I'm more optimistic than I thought I would be, but you know, there's definitely challenges ahead.

This is just fascinating! Is there anything else you'd like to discuss?

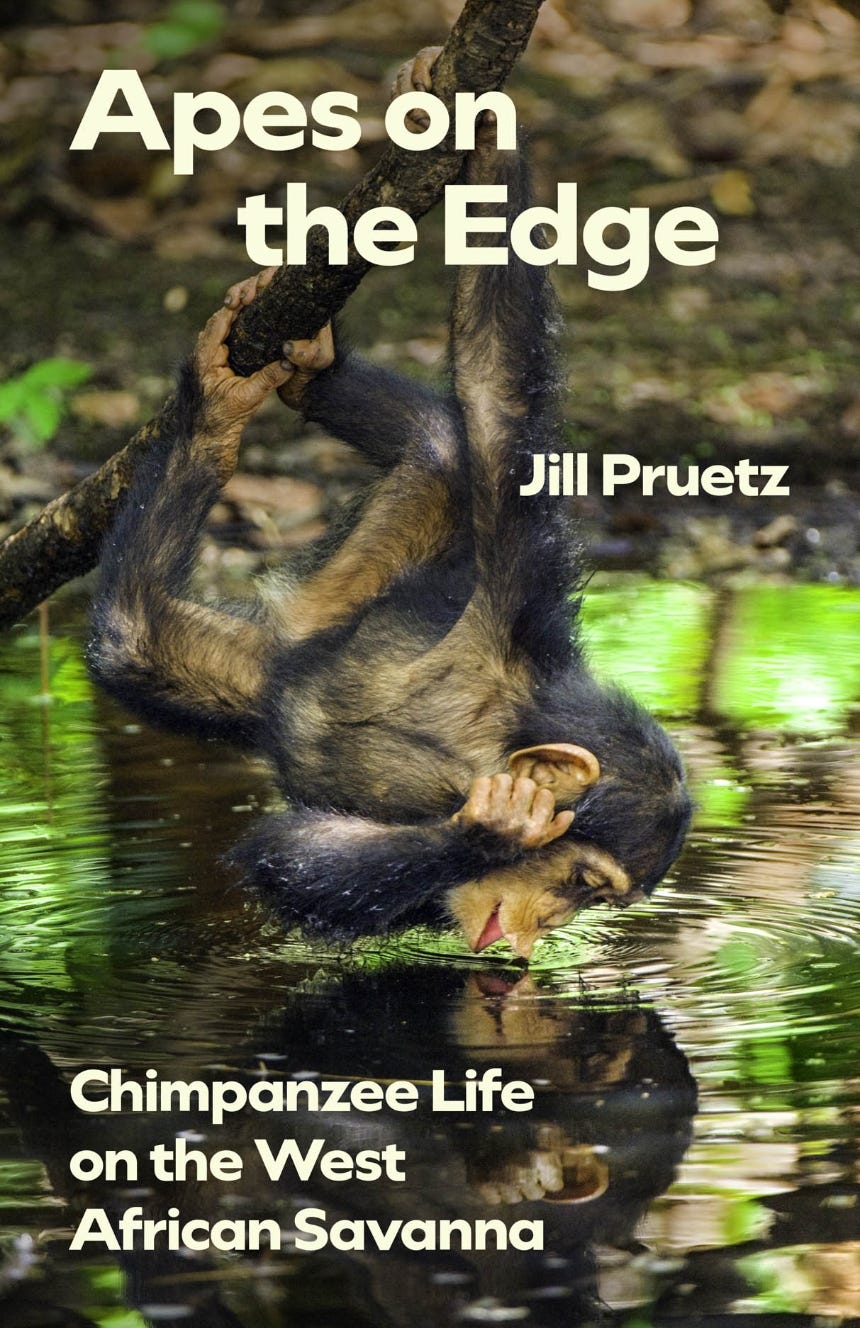

I did write a book! It’s coming out in January 2025. It’s called Apes on the Edge. And so in this book, I talk a lot about the community of chimps, of course, but then the human side of things as well. The last couple of chapters are really focused on that. I think it's going to be a good read. That's what I've been told, but also it just tells something that you don't always get from scientific articles. And one of these is that, you know, without those local people and their cultural traditions here, we probably wouldn't have these chimps. That's not something we usually associate with conservation, at least in the past, we haven't. We’re better about it now. It’s really important to include the local people in all the different phases of study, and I couldn't have done it without them.

So I do talk more about that, logistics of the project, stuff that goes on, the people behind the scenes. And a lot on the chimps, too. There's one whole chapter just on hunting.

I hope that this book will enable a lot of people to see the whole story and not just what's put out in scientific circles. You know, just to see the whole Fongoli story. I’m excited about it! Hopefully it'll go well.

Thank you so much for everything that you do.

Thank you.

Fun read! I have ordered the book. It's about $25 for an ebook, PDF, or paperback.

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/A/bo238989411.html

Great interview Sam. I find chimpanzees very daunting- depressing actually...they are so very like us, it seems, in violence, but lack some of the communal altruism we have.