De-Extinction Diaries: Mapping Historic Passenger Pigeon Nesting & Roosting Sites

I got to contribute to a really cool science project recently - and you could too!

Longtime readers of this newsletter may recall that I’ve long been fascinated by the story of the extinct passenger pigeon, Ectopistes migratorius, and particularly the bold efforts by paleogeneticist Ben Novak and the team at Revive & Restore to genetically resurrect the species. If successful, this endeavor has extraordinary potential to help restore ecosystem diversity and carbon sequestration in North America’s eastern forests1.

The genetic side of Revive & Restore’s work is now well underway; the passenger pigeon genome has been sequenced, and if all goes well we might see the first new passenger pigeon hatchlings in over a century as early as the 2030s. (Here’s my full interview on this for more background!).

In 2024, I’ve had the pleasure of participating in some of the groundwork for this fascinating project by georeferencing part of the foremost existing database of historic passenger pigeon records. This article is about that work, and what comes next.

In the middle of the twentieth century, a Wisconsin ornithologist named Bill Schorger put a lot of hard work into studying the legacy on the passenger pigeon, combing through old newspapers, local history, and personal recollections to accumulate a vast corpus of thousands notes on places where they had once been seen. This was then digitized by another guy, Professor Stan Temple, and made publicly available.

My project for Revive & Restore this year was to manually review the subset of Schorger’s database that consisted of documented nesting and roosting sites, then georeference (i.e. map) them, getting a clearer picture of where this species once nested and roosted across North America. What that looked like in practice2 was using QGIS to plot points and polygons based on the relevant information associated with each record in Schorger’s notes, like “4 24 1888 pigeons roost in big woods on yellow river 15 miles from city [Prairie du Chien]”, or “1878 nesting 26x5 miles; hatched 3 times; impenetrable swamp on Manistee River [Michigan]” or "roost in alder bushes covering 6 acres; 5 miles south of Oakland [Maryland].”

There were over 1,000 of these records describing over 600 individual nesting and roosting sites, and we mapped them all!

The drumbeat of unregulated mass hunting that led to their extinction was regularly visible in this elegiac scrapbook passion-project of a database, with records very often including passages like “hunters take 397,800 weekly,” or “Shipped 100 barrels of birds a day,” or “There were 300 to 500 nests per tree, 60,000 pigeons were harvested by using decoys.”

Every shotgun was aimed at them and everybody feasted on pigeon pies, and not a few of the settlers feasted also on the beauty of the wonderful birds.

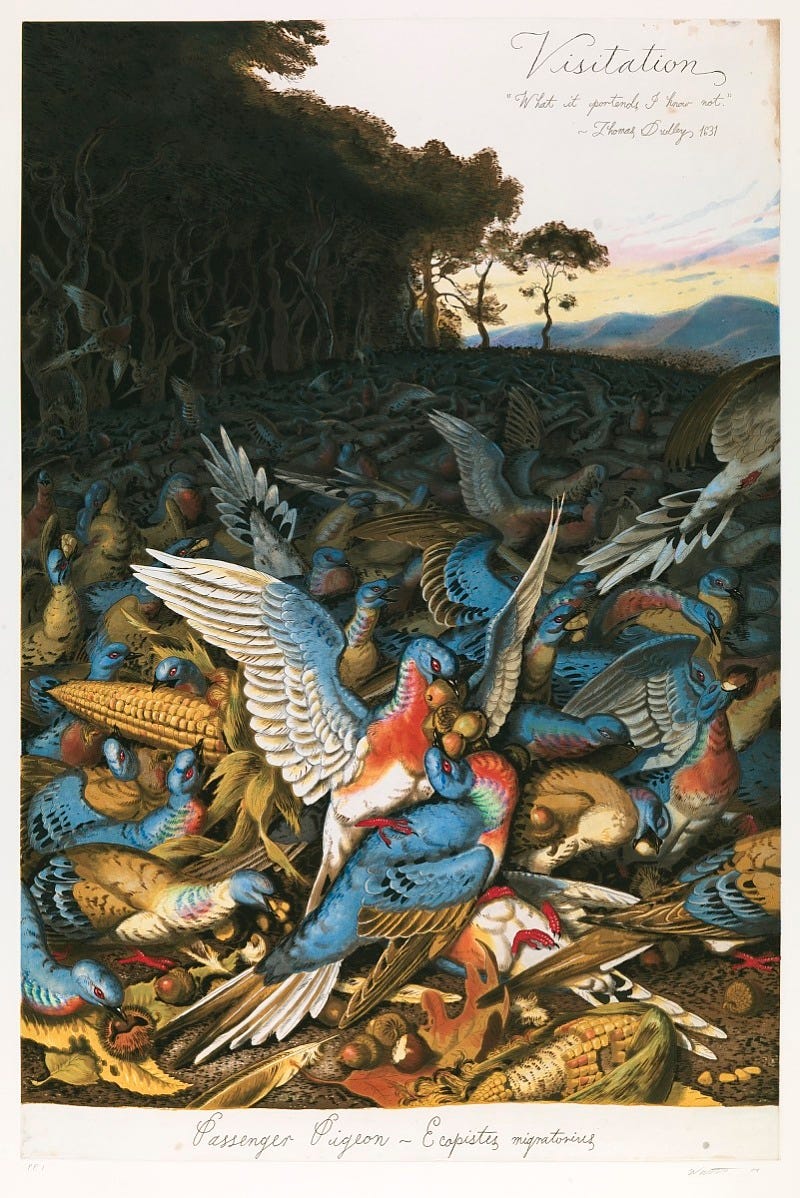

The breast of the male is a fine rosy red, the lower part of the neck behind and along the sides changing from the red of the breast to gold, emerald green and rich crimson.

The general color of the upper parts is grayish blue, the under parts white. The extreme length of the bird is about seventeen inches; the finely modeled slender tail about eight inches, and extent of wings twentyfour inches. The females are scarcely less beautiful.

"Oh, what bonnie, bonnie birds!" we exclaimed over the first that fell into our hands. "Oh, what colors! Look at their breasts, bonnie as roses, and at their necks aglow wi' every color juist like the wonderfu' wood ducks. Oh, the bonnie, bonnie creatures, they beat a'!

Where did they a' come fra, and where are they a' gan? It's awfu' like a sin to kill them!"

-John Muir, recalling passenger pigeon hunting in his childhood.

The scale at which passenger pigeons were killed also underscores the sheer size of the passenger pigeon flocks that once graced the continent of this writer’s birth.

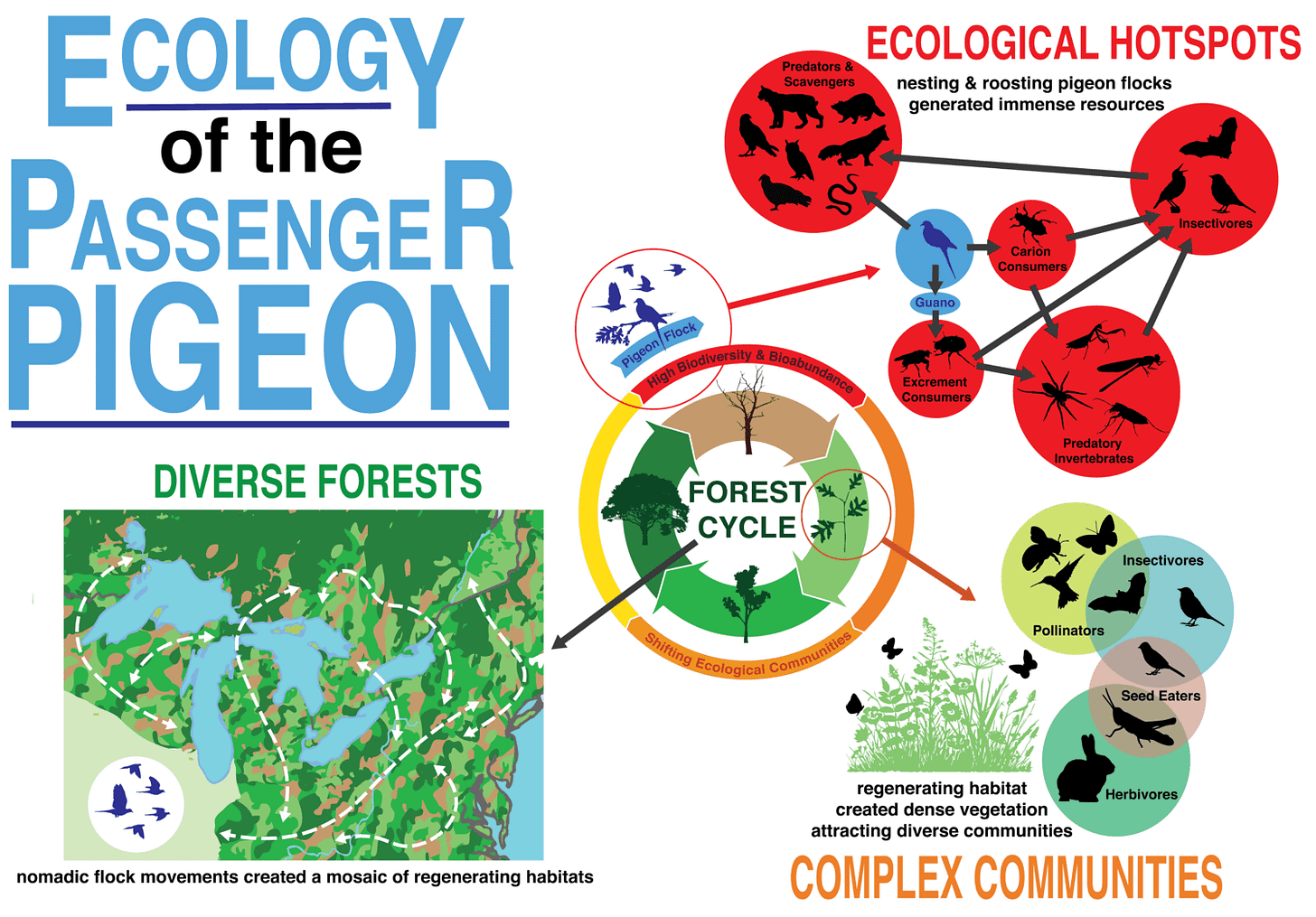

Many contemporary scientific observations highlight their profound ecological impact, like a biological storm that semi-randomly creates rolling opportunities for change in the forest ecosystem. Passenger pigeon roosts were known to break up the canopy by their sheer weight on trees’ branches, as well as hyper-fertilizing the patches of forest they’d nest in with their droppings, which together amounted to a rapid infusion of more light and nutrients that would encourage more carbon-sequestering fast-growing young saplings to spring up. A rich and diverse habitat mosaic was formed by their presence.

With effects like that, many ecologists think that there might still be readable traces of passenger pigeons’ impact in the soil, even one or more centuries later. And in the project I was part of this year, we just came up with actual coordinates for the world’s foremost database of nesting and roosting sites!

So now, Revive & Restore is trying to reach out to people who own land on what we think are the sites of historic passenger pigeon nesting and roosting colonies! Here’s how our draft handout to potentially interested landowners will put it:

If any trees used by the historic flock are still present, we can begin to answer questions about the tree growth rates, which would likely have been boosted by manure from the pigeon colony.

Historic first-hand accounts suggest the year after a nesting, the forests were the greenest and lushest to be found. We wonder if the “fingerprint” of this historic pigeon colony might still be detectable in the chemistry of the soils and the rings of the trees, and this is what we seek to learn from your land.

We’d also love to learn what may be known locally about the historic passenger pigeon nesting event in your neighborhood. If you are interested, we would like to measure soil and wood chemistry and tree growth rates on your land to detect their historic presence. Depending on what we find, we are also looking for a few sites for a possible more detailed study.

We’d be happy to tell you more details if you’re interested! Our measurements will inform genetic studies to see if passenger pigeons can be brought back to life using the DNA present in preserved specimens.

-Revive & Restore team

So, I’d like to wrap up this article with a possibility for audience participation in this project! If you, the reader, happen to own some land (even a backyard) in the United States anywhere east of Nebraska, especially if it’s in an upper Midwest state like Wisconsin or Michigan where there are lots of Schorger records, feel free to check out the web map of our georeferenced findings and see if your area is on it!

If you’re interested, you can reach out to Revive and Restore through steve AT aeinstitute.org3, and a team of great folks (likely not me, to be clear, but other awesome people!) will follow up with you.

And for everyone, I hope I’ve succeeded in sharing a little of my excitement about this amazing ecological renaissance in the making! We can see passenger pigeons take to the American skies again, in our lifetimes. Let’s go!

For more detail, here’s an extract from my unpublished proto-methodology section:

Beginning with the dataset of Schorger’s unpublished notes on passenger pigeon records (digitized and compiled by Professor Stanley Temple), we selected all records coded as Nesting Sites and Roosting Sites (n = 1052), manually collated the data, and georeferenced them in two batches in QGIS by reading Schorger’s Notes sections and manually plotting the described passenger pigeon nesting sites and roosting sites, as polygons or points depending on available information. Notably, there was not a one-to-one relationship between records and mapped sites; for example, large nesting events (e.g. Petoskey 1878) generally had a large number of records clearly referring to the same time and place, and these were mapped as one polygon, leading to substantial consolidation.

The final georeferenced events data (n = 622) is visualized in an ArcGIS Online web map for ease of reference. Click on the points and polygons to see the original Schorger Notes fields and get a sense of how/why they were georeferenced.

Email address configured without the @ sign to deter bot scrapers.

What a great topic for a story! So much to work with!

I thought chestnuts were a primary food source of the passenger pigeon. When a disease caused the near extinction of the American Chestnut, the loss of a primary food source likely hurt their survival too.