The Weekly Anthropocene: Big Cats!

A Deep Dive into the Wild, Weird World of Humanity and its Biosphere

Big cats are some of the most majestic (and frankly cool) creatures on Earth. They’re also some of the most imperiled: all seven big cats1 are listed as “population declining” by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)2. However, this writer noticed that it was difficult to find a good single source summarizing how each of these species is doing in the never-ending quest to survive and thrive in the Anthropocene, a general check-in on “how they’re doing.” In this article, The Weekly Anthropocene is trying to provide such a check-in, compiling current conservation status, best available population estimates, and some interesting bits of news and science for each big cat.

Lions

Tigers

Jaguars

Leopards

Snow Leopards

Cheetahs

Pumas

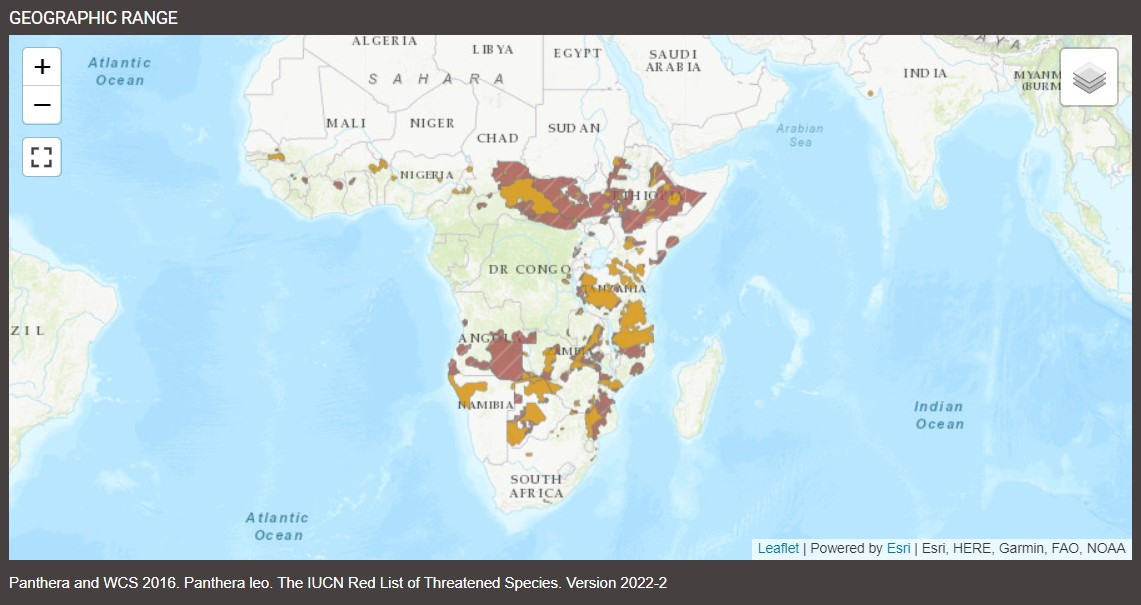

Lions (Panthera leo)

IUCN Ranking: Vulnerable

Estimated Wild Population: 23,000-39,000

Continents: Africa, small population in Asia

Lions are iconic.

Although these things are difficult to objectively measure, lions are probably the most studied, most well-known, most recognizable, and overall most popular big cat.

However, stereotypes about lions (everyone feels that they basically know what they’re like) often obscure a more nuanced picture of their ecological role. For example, take the oft-depicted lion-hyena scavenger-hunter relationship. Lions coexist with the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) across much of their range, and the Disney movie-supported mythos is that lions are noble hunters while hyenas are skulking scavengers. However, actual field studies reveal that lions scavenge more of their food than hyenas, and very often steal kills from hyenas. In fact, lions scavenge around 50% of their food (hunting for the rest), while hyenas hunt for around 95% of their food! It’s more accurate to describe hyenas as hunters and lions as scavengers than the reverse-and it makes no sense to try to collapse these different ways of surviving on the savanna into a morality play. The Lion King lies.

Lions have been under severe threat in recent decades, and are declining in most of their range due to hunting, snaring, poisoning by ranchers, and habitat destruction. They have been entirely extirpated from several West African countries; Gabon is thought to have only one individual lion left. The IUCN lion status assessment found that from 1993 to 2014, lion population has grown by 12% across five countries (Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and India3) but declined by 61% everywhere else in its range, leading to an overall 43% population decrease for the species as a whole. So lions are doing fairly well in a southern stronghold, but are losing ground across the rest of the African continent.

Several interesting conservation efforts are working to remedy this. For example:

Big cat conservation NGO Panthera is building cattle-protecting “boma” enclosures in Zambia to prevent lions killing cattle and being killed in retaliation by ranchers

The Maasai people of Kenya’s traditional manhood rite involved sending a young warrior out to kill a lion armed only with a spear and a shield, but they have now largely replaced this with the “Maasai Olympics,” a major community event with javelin, high jump, and running competitions for young men to prove their might

Stronger anti-poaching efforts led Senegal’s plummeting lion population to begin to recover, from 10 to 15 individuals in 2011 to 30 to 40 individuals in 2022.

Rather extraordinarily, several lions have recently managed survive and thrive in the wild with only three legs (including a female in Zambia and a male in Uganda) after losing a limb to these pervasive poachers’ snares.

South Africa also says they’re slowly moving towards finally banning its horrific “lion farming” industry, where currently over 10,000 lions are raised and bred in appalling conditions to be later killed for sport in “canned hunts” or for their bones to sent to Asia for “traditional Chinese medicine.” The end to that nightmare can’t come soon enough.

In sum, lions are in serious trouble, picked off by poaching, mutilated by snares, and brutalized for their bones. But they still have several well-defended stronghold areas, and people are working to prevent them disappearing elsewhere. As with almost every other aspect of the natural world in the Anthropocene, the next part of their story is up to us.

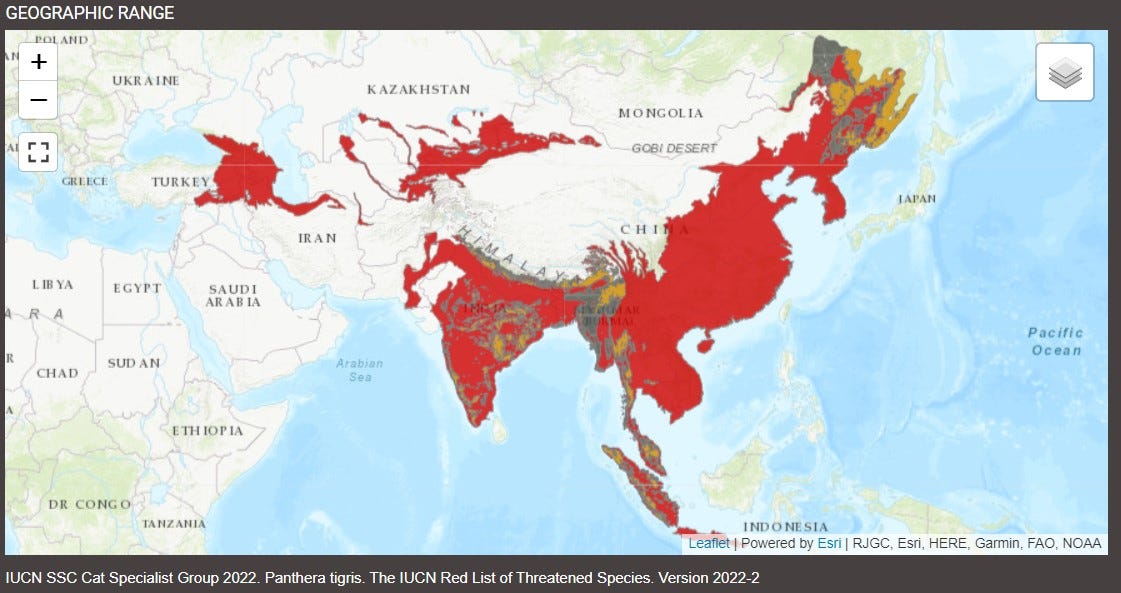

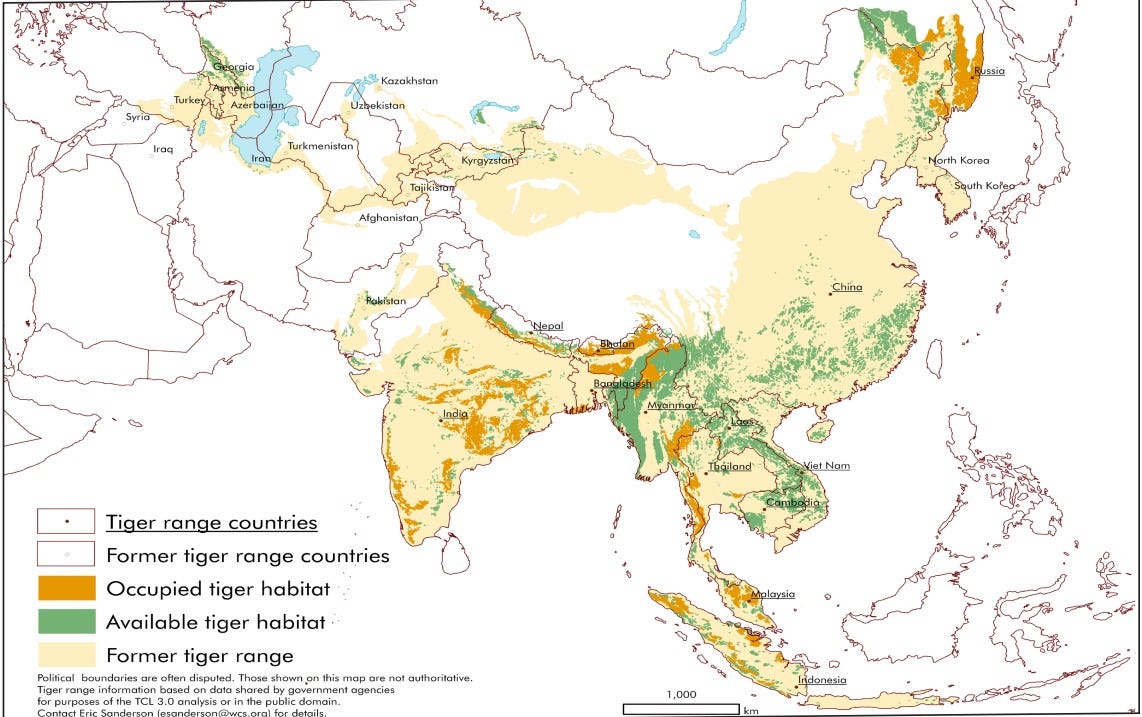

Tigers (Panthera tigris)

IUCN Ranking: Endangered

Estimated Wild Population: around 4,500

Continents: Asia

Tigers are targets.

The most threatened of the big cats (IUCN ranking: endangered), tigers are ruthlessly targeted by international crime rings for their skin, bones, and organs, demand for which is supercharged by China’s quasi-legal market for dead tiger bits as ingredients in “traditional Chinese medicine.” The wild tiger population is currently under 5,000, but there are an estimated 5,000 or more kept in horrific “tiger farms” in China, and an estimated 10,000 tigers captive in the United States, most of them by unregulated private owners. (Although in the US captive tigers are mostly not in explicitly murder-y “farms” but in the hands of sideshows, circuses, and misguided exotic pet owners, many of them are still likely being clandestinely killed to sell their body parts to China. It’s hard to keep track of this shadowy industry). A recent report found that tiger parts equivalent to at least 3,377 dead tigers were confiscated between January 2000 and June 2022, and there were presumably a lot more that weren’t confiscated. No other cat species-and very few other species, period-have to endure anything close to this level of relentless, well-funded persecution.

However, despite these threats, tiger conservation has actually made considerable progress in recent years, thanks to several key countries stepping up their proactive protection efforts. As this newsletter previously reported, in early 2022 an array of leading conservation organizations, including WWF, IUCN, WCS, and Panthera, issued a joint status report on progress made in tiger conservation since 2010. It found that wild tiger numbers have been increasing since 2016, a history-making halt to the decades-long decline of wild tiger numbers. The global wild tiger population has risen from an estimated 3,200 in 2010 to an estimated 4,500 wild tigers in 2022 (spread across 4-6 living subspecies, from the Siberian tiger to the Sumatran tiger), compared to an estimated historical norm of 100,000 wild tigers in the year 1900. (Unlike many other big cat species, we have a pretty good idea of how many wild tigers there are, in part because it’s hard for wild tigers to survive poachers’ onslaught outside well-surveilled and ranger-protected parks).

This progress is notably geographically uneven, with some countries growing their tiger populations substantially and others plummeting to zero.

Between 2010 and 2022, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam lost their last remaining tigers to poaching, bringing the number of tiger range countries down to 104. (Here's an in-depth article from the always-excellent Mongabay on how Laos lost its tigers).

Indonesia, Malaysia, and Myanmar have seen their tiger populations shrink in recent years due to poaching and development pressures, with civil war-stricken Myanmar a particular danger zone.

However, India (home to the majority of wild tigers) saw slow but steady growth, with the 2018 tiger census estimating 2,967 tigers in India, up from 1,706 in 2010 and 1,411 in 2006.

Siberian (aka Amur) tigers increased their numbers and range in Russia and China, rising from just 20 to 30 individuals in the 1990s to over 300 today.

Thailand appears to be at least holding steady, with well-protected national park complexes.

And the small Himalayan nation of Nepal did spectacularly, nearly tripling its tiger population from 121 in 2010 to 355 in 2022.

Even the captive tigers of America received some hopeful news in 2022, as President Biden signed into law in December the Big Cat Public Safety Act, which for the first time institutes a federal ban on keeping big cats as “pets.”

Overall, 2022 brought good news for all who hope that Earth will be home to tigers forever. It’ll still be a very difficult fight, but with ongoing collaborative conservation efforts and unrelenting law enforcement pressure on poaching gangs, there’s now a good chance that humanity can ensure that this majestic cat thrives in the Anthropocene.

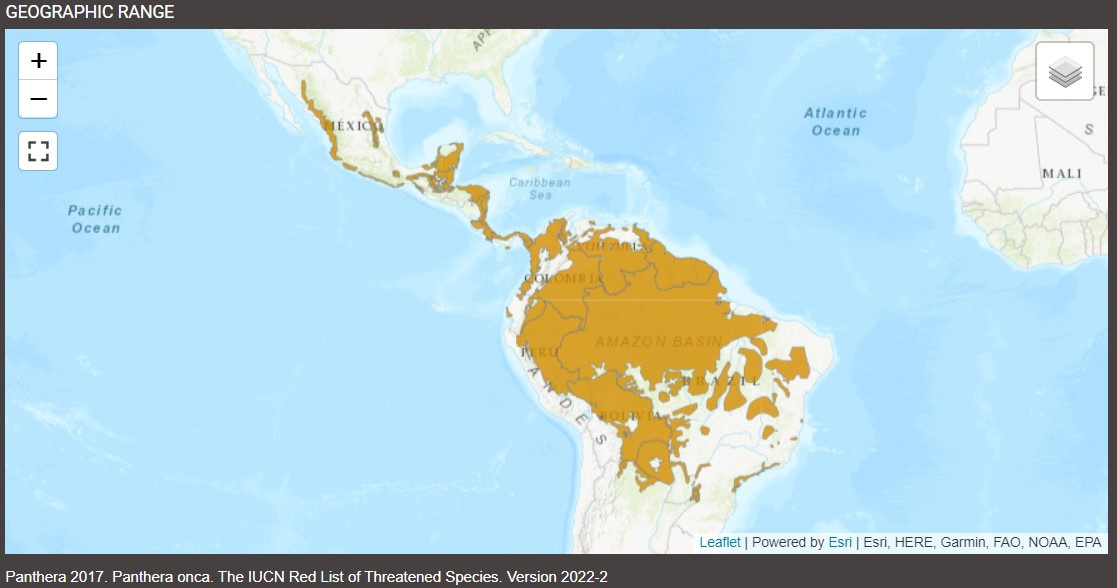

Jaguars (Panthera onca)

IUCN Ranking: Near Threatened

Overall Population Change:

Estimated Wild Population: 64,000-173,000

Continents: North America, South America

Jaguars are awe-inspiring.

Jaguars were widely revered by early American civilizations, inspiring Olmec were-jaguar statues, Aztec “Jaguar Warriors,” several Maya jaguar gods, and the Moche culture of ancient Peru’s jaguar pottery. Their name comes from the Tupi-Guarani word “yaguara” meaning “the beast that kills its prey in a single bound.” Jaguars have an extremely powerful bite that allows them to pierce tortoise shells and mammal skulls, and are by far the best swimmers among the big cats, even hunting caimans in the water. They may well be this writer’s favorite big cat5.

In the 20th century, jaguars were widely hunted for their skins and killed by ranchers seeking to protect their livestock (a perennial problem for many big cat species). They were extirpated from much of their geographical range; jaguars once ranged as far into the United States as Colorado and Louisiana, for example. (Here’s a great article on the history of jaguars in North America). However, compared to most other big cat species, jaguars are doing quite well: current population estimates range from 64,000 to 173,000 wild jaguars, ranging from Mexico to Argentina.

However, they still face many challenges:

Jaguars have recently suffered substantial losses due to climate change. Massive wildfires swept through Brazil’s verdant Pantanal wetlands in 2020, killing, injuring, or displacing over 700 of the region’s 1,600+ jaguars (here’s the study). Much of the habitat damage could be long-term, as the wetland ecosystem (unlike many forests) isn’t “used” to fires and its species community might not be able to bounce back very quickly.

Another study estimated that likely over 1,400 jaguars have been killed or displaced by fires and deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon in 2016-2019. This has likely only gotten worse as deforestation has surged since 2019 under Bolsonaro.

One emerging threat to jaguars is particularly disturbing: Chinese triads are starting to target Latin American jaguars to sell their body parts as “American tiger,” betting that Chinese consumers won’t know or won’t care about the difference. If this escalates to anywhere close to the level of persecution tigers face, it could become a very serious threat to the species.

Fortunately, there also exists a dedicated community of jaguar conservationists, some of whom were at the heart of the epic real-world adventure stories that fascinated this writer as a child and sparked a lifelong interest in wildlife conservation. Dr. Alan Rabinowitz’s jaguar research in Belize led to the founding of the Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary in 1986, the world’s first jaguar preserve. This dangerous odyssey was detailed in his book Jaguar. (See The Weekly Anthropocene’s review here). Before his tragic death in 2018, Dr. Rabinowitz also spearheaded the Path of the Jaguar initiative, a pioneering mega-project working to ensure connectivity between all jaguar habitat from Mexico to Argentina, that is still being pursued by Panthera, the big cat conservation NGO he cofounded. (Here’s a great article about his life). Several Panthera-funded projects working to conserve jaguars in recent years have been highly innovative; one project used AI analysis of sounds from a network of acoustic monitoring units to catch poachers in Honduras parks, another created a conflict response unit to deploy new defenses for cattle herds predated on by jaguars in Costa Rica (thus avoiding revenge killings by angry ranchers), and a third is developing jaguar ecotourism in Colombia’s Llanos grasslands.

Another interesting aspect of jaguar conservation is their potential reintroduction to (or at least formal federal protection in) the United States, as several jaguars from northern Mexico have wandered across the border and lived in Arizona or New Mexico in recent years. This became a fairly big media story, but isn’t actually that important for the future of the species; we’re talking single-digit numbers of individual cats here. It does produce some fascinating wildlife stories, though: in recent years a jaguar known as "El Jefe" managed to circumvent US border walls to go from Mexico to Arizona and back.

Overall, jaguars are suffering from climate change and the illegal wildlife trade like many other species, but have a still-robust population and innovative conservationists already on their side. This writers feels confident that their future can be bright.

Leopards (Panthera pardus)

IUCN Ranking: Vulnerable

Estimated Wild Population: “No robust estimates,” somewhere in the tens of thousands

Continents: Africa, Asia

Leopards are adaptable.

Leopards have the widest distribution of any big cat, from the jungles of Java to the snows of Siberia to the deserts of Saudi Arabia to the mountains of the Himalayas to the savannas of South Africa. They’ve managed to survive in a lot of territory where lions and/or tigers have been wiped out, thanks to being smaller and stealthier, able to live in human-dominated landscapes, and eat a wide variety of prey. They’re perhaps the most arboreal of the big cats, often carrying their kills into trees to eat in a safer space. A recent study of leopards in the Sabi Sands of South Africa found that they’re also surprisingly un-territorial with each other, “good neighbors” where both leopard males and females share about 50% of their home range with opposite-sex leopards and about 25% with other leopards of the same sex.

There are “no robust estimates” of leopard population size (though it’s likely considerably larger than, say, cheetahs, tigers, or snow leopards, somewhere in the tens of thousands), but it is known that many populations are declining. Like many other big cat species, leopards are doing relatively well in some areas and being wiped out in others.

In India, leopards have benefited substantially from the network of protected areas conserved for the benefit of tigers throughout the country. A 2014 survey found 7,910 leopards sharing habitat with tigers, and an estimated 12,000-14,000 across the whole country including non-tiger habitat. It’s unclear if this population is increasing or decreasing.

Leopard populations are decreasing across sub-Saharan Africa due to increasing conflict with humans, but good numbers are hard to come by.

There are around 300 Javan leopards left, with a declining population trend worsened by their fragmentation across many small patches of landscape.

Sadly, a 2016 study found that leopards had been devastated in Southeast Asia, mostly due to the illegal wildlife trade. The species is extirpated in Laos and Vietnam, nearly gone in Cambodia and China, and greatly reduced in Malaysia, Myanmar, and Thailand.

The Amur leopard population in the Russian Far East is critically endangered and extremely rare, but has made a bit of comeback recently under stricter protection, with the population increasing from an estimated 19 to 26 individuals in 2007 to over 100 in 2021.

In some areas, leopards have recently shown truly extraordinary flexibility in adapting to human-dominated environments. In Mumbai, 40 to 45 leopards live in Sanjay Gandhi National Park, an oasis of forest in the heart of the 23 million person metropolitan area. Since at least 2012, some leopards, given names like Adarsh Nagar, Chandani and Bindu, have even grown comfortable walking through fully built-up human neighborhoods. (Here’s an excellent article on them).

There have been some serious conflicts; in late 2022 leopard attacks spiked and a toddler was killed, which led to the Forest Department trapping two leopards thought to be responsible. However, conflict overall is shockingly low for a city of this size with leopards in the middle of it, and the leopards are likely saving many human lives on net, as they prey on the city’s feral dogs that carry rabies. A study recently calculated that the Mumbai leopards likely eat 1,500 dogs annually, likely saving tens of thousands in municipal dog control and treatment costs, preventing over 1,000 dog bites (on humans) and preventing up to 90 human rabies cases per year (under “worst case scenario” rabies assumptions). The leopards may also be preventing the feral dog population from expanding, so if they were gone, there would likely be an exponential rise in dog bites. (Here’s the study). This is a strange and fascinating balance that appears to be forming, and a very “Anthropocene” story.

In other leopard conservation news, the Saudi Arabian monarchy launched a program in 2019 to revitalize the imperiled Arabian leopard population in the mountainous Al-'Ula region. Panthera biologists are currently working to find how many are left and where they live. And the Shembe religious movement of South Africa’s Zulu people, who traditionally use leopard pelts as clothing during their dancing gatherings, have started to transition to synthetic leopard pelts. Supportive conservation groups hope that this will remove the recurring religious ceremony-related demand for pelts that kills over 1,500 leopards in the region every year.

Leopards are a fairly “quiet” big cat species in terms of their impact on human consciousness, often overshadowed in the public eye by the lions and tigers that share much of their range. But they have been extraordinarily resilient and adaptable in recent years (highly valuable traits on today’s fast-changing planet!), and have a decent chance of surviving long into the future. Hopefully we can learn more about them and get some robust overall population numbers as well!

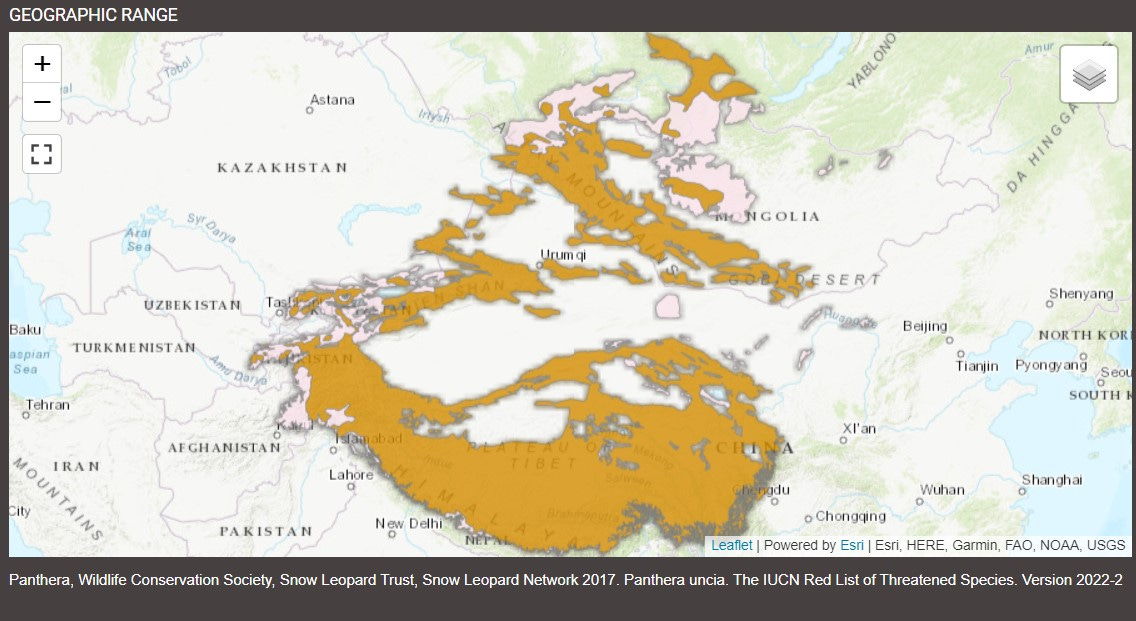

Snow Leopards (Panthera uncia)

IUCN Ranking: Vulnerable

Estimated Wild Population: Probably low-ish, perhaps between 3,900-10,000

Continents: Asia

Snow leopards6 are elusive.

Known as “the ghost of the mountains,” this big cat is native to the Himalayas and the other mountain ranges of the Central Asian plateau7, and is legendarily hard to spot. The most famous book about snow leopards, The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen, is a beautifully written narrative of Himalayan ecology and culture, Buddhism, surviving loved ones’ death, and finding meaning in life. However, it contains no snow leopards: Matthiessen never saw one despite embarking on an arduous two-month expedition to a remote region of Nepal. At the time of his expedition in the 1970s, only two Westerners had seen a wild snow leopard in the previous twenty-five years.

We know considerably more about snow leopards now thanks to modern camera traps and radio tracking. (Although many modern wildlife surveying techniques are still very difficult in the snow leopards’ mountain habitat, where cliffs scatter radio signals and the cold perma-freezes genetic material in scat, making it hard to tell if samples are from a current population or long-dead individuals). Radio telemetry studies in Mongolia have found that snow leopards have very large individual home ranges, up to 200 square kilometers for males (that’s larger than Manhattan and the Bronx combined!) but it’s unknown if this generalizes to the rest of their range. Another recent study from Mongolia found that expansion of goat herds for cashmere wool farming was encroaching on their habitat. Climate change and poaching are probably harming snow leopards somewhat, but we don’t really know how much.

Overall, they’re still woefully understudied:

A quoted search on Google Scholar reveals less than 5,200 papers with “Panthera uncia” in them, compared to over 14,000 papers for “Acinonyx jubatus”, over 20,000 papers each for the scientific names of leopards, jaguars, pumas, and tigers, and over 30,000 for “Panthera leo”.

A 2021 paper on snow leopards says “It has been suggested that there could be around 3900–8745 snow leopards globally, but these numbers are largely based on opinions.”

And the New Yorker recently quoted eminent biologist George Schaller as saying, “There are thousands and thousands of square miles [of snow leopard habitat] that no one has ever checked. Nobody knows if the population has increased or decreased.”

A new international effort called the Population Assessment of the World’s Snow Leopards (PAWS) was launched in 2017 by an array of countries and NGOs in an effort to figure out just how many there were. The original plan was to have results by 2022, but according to Chinese news articles in 2022, their surveys are still ongoing.

So the answer to “how are snow leopards doing?” is…nobody really knows! We might know more in a few years. Seems like there’s a lot of research opportunity here for some universities, NGOs, and young biologists up for adventure!

(Also, just off the top of this writer’s head, has anyone ever tried using AI image recognition with the new ultra-ultra-high-resolution satellite datasets from companies like Planet to look for individual snow leopards, as has been done with elephants, penguins, walruses, and more? Might be worth a shot).

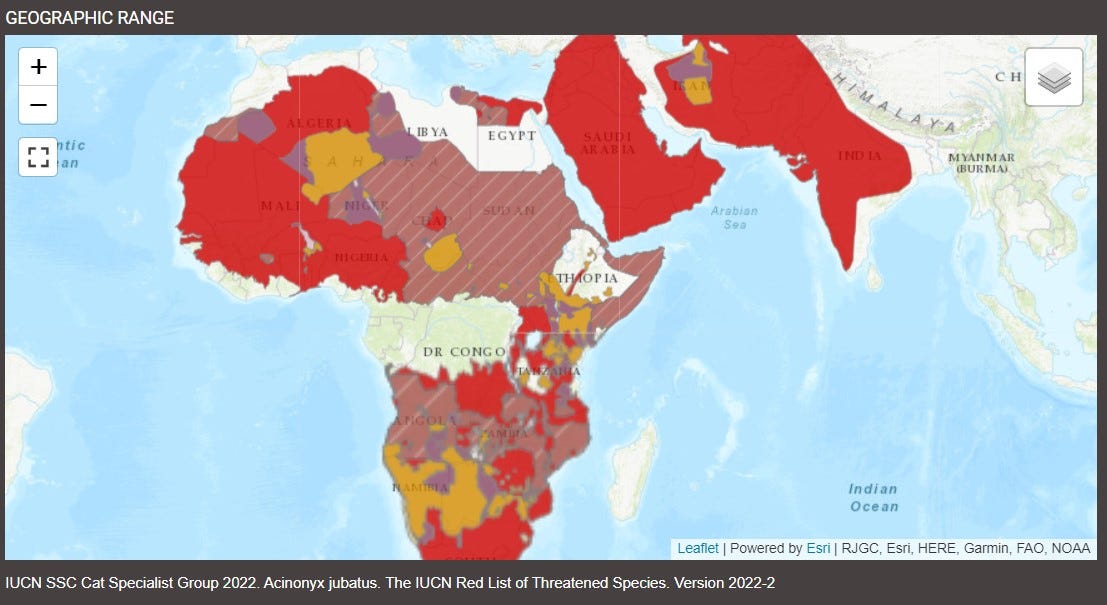

Cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus)

IUCN Ranking: Vulnerable

Estimated Wild Population: around 6,500

Continents: Africa, small population in Asia

Cheetahs are weird.

Among the big cats, if there’s an exception to a rule, it’s likely the cheetah. Let us count the ways:

They’re in their own genus, Acinonyx, which isn’t very closely related to any other cats.

They’re famously super-fast, but that also makes them really vulnerable. Cheetahs’ light, speedster build means they almost always lose in a fight to other savannah predators; hyenas and lions routinely steal their kills and even eat their cubs in the wild.

Due in large part to such attacks from other species, over 90% of cheetah cubs die before reaching adulthood, and that’s in optimal wild conditions, without counting human pressures.

Cheetahs are very difficult to keep in captivity and incredibly difficult to breed in captivity, tending to spontaneously develop a wide range of highly contagious and seemingly unrelated diseases as soon as you confine them.

As if that wasn’t enough to deal with, cheetahs are all quite inbred, having undergone two major genetic bottleneck events leaving them on the edge of extinction; the first around 100,000 years ago and the second around 12,000 years ago.

And on top of all that, humans have persecuted cheetahs immensely over the last century. Farmers often shoot cheetahs to protect their livestock, a tragic motif of large carnivore conservation the world over. Cheetahs, like many other species, are vulnerable to climate change and habitat disruption. However, probably the biggest threat to the cheetah at the moment is the illegal wildlife trade, which unlike with tigers focuses on live cheetahs. Hundreds of cheetah cubs are snatched from the wild in Africa to be sold as exotic “pets” in the Middle East. Owning a cheetah is a social media-driven fad among the ultra-rich of Saudi Arabia, who buy the cats on Facebook and WhatsApp, then show them off on Instagram. Cheetahs generally die quickly in captivity, and for every wild-caught cub sold to buyers, three or four die in transit. Despite putative law enforcement efforts, the trade is ongoing. As a result of all these factors, there are an estimated approximately 6,500 African cheetahs and as few as 12 Asiatic cheetahs8 left.

That said, there has been some positive news for cheetah conservation recently, though cheetah numbers are still declining precipitously and there’s been nothing so grand as the full-on turnaround in wild tiger numbers. For example, the Cheetah Conservation Fund has had success recently by with a program distributing livestock guarding dogs to farmers in Namibia, to prevent revenge killings of livestock-eating cheetahs.

And eight cheetahs from Namibia were dramatically reintroduced into India in September 2022, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself present for the release. The map above now needs a little orange dot in central India. (Here’s the story of the reintroduction from a supporter’s perspective). This reintroduction has been controversial; the cheetahs are from the African not Asian subspecies and so are not quite the same as the cheetahs that went extinct in India in the 20th century, they may not survive without active human intervention, and the cheetah reintroduction program attracting lots of attention and resources as a “shiny new thing” while many other Indian species are relatively under-supported. However, The Weekly Anthropocene thinks this is probably net good for the species; the very PR-heavy-ness of the reintroduction means that it would be really embarrassing for the Modi administration to let the new cheetah population in India die off, so they’ll probably invest in keeping them safe. This population may serve as valuable insurance if the situation for cheetahs in Africa worsens.

Cheetahs have some serious natural disadvantages, and are under sustained attack from many sides. They still have a chance to make it, but could really definitely use some more concerted conservation and anti-poaching efforts!

Pumas (Puma concolor)

IUCN Ranking: Least Concern

Estimated Population: No good estimates, but probably high. Over 100,000? Maybe?

Continents: North America, South America

Pumas9 are everywhere.

This cat of many names has the largest known range of any native terrestrial mammal in the Western Hemisphere, with populations present in wildly diverse ecosystems ranging from the snowy mountains of British Columbia to the depths of the Amazon Rainforest. Pumas can even survive in relatively urban areas: a male known as P-22 lived in Los Angeles’ Griffith Park for ten years (monitored by a radio collar and occasionally given health check-ups by park rangers) until his death in 2022. This demonstrates some pretty extraordinary behavioral plasticity, making them well-adapted to survive the fast-changing Anthropocene.

Pumas are cryptic, meaning they mostly hide from humans (unlike many other big cats), meaning no one is exactly sure how many there are and we’re only now learning some basic facts about their ecology. Pumas are the least threatened of all the big cats: they’re ranked as “Least Concern” by the IUCN. Their population is tentatively thought to be declining overall due to hunting in its Latin American range, but they’re expanding and multiplying in North America10. There were estimated to be at least 10,000 pumas in the western US alone in the early 1990s, and there are probably a lot more now, as more pumas are being seen and they’re starting to move back eastward, recolonizing parts of the continent where they’d previously been wiped out by hunters. (And benefiting humans along the way: one study found that pumas’ recolonization of South Dakota had reduced deer-vehicle collision costs by over $1 million). There’s a lot of room left to expand: a new study identified 17 landscapes in the Eastern US that are ideally suitable as puma habitat, from Maine to Wisconsin!

Humanity has also been learning a lot more about pumas recently, despite their secretiveness, much of it thanks to a pioneering long-running research program studying pumas in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Long thought to be solitary cats, pumas are actually highly social. A landmark camera trap study revealed that pumas are organized into local friend groups with every single puma they followed engaged in food sharing with other pumas. This is a major revelation that changes science’s entire conception of what puma lives are like!

Another recent study found that pumas have ecological relationships of some sort (i.e. predator/prey, competitors for food, scavenging from their kills, etc) with a staggering 485 different species, placing them at the heart of the Americas’ food web.

Other studies, supported by major big cat conservation NGO Panthera, found that pumas compete substantially with gray wolves for the same food and habitat.

And that pumas are swimming around Puget Sound and the Salish Sea, able to access thousands of the little islands in the area.

Finally, the highest scavenger species density ever recorded anywhere on Earth was recently found at the site of a puma kill.

Pumas have also recently received substantial human conservation support in key locations across their range. For example, in the wake of P-22’s death, Los Angeles is building the world’s largest wildlife crossing to allow pumas to cross the 101 Freeway, helping isolated cougars in the Santa Monica Mountains to find new breeding partners. And conservationists are developing puma conservation and ecotourism projects in the mountains of Chile, where pumas were often hunted.

So overall, pumas are doing very well in the Americas of the Anthropocene! The future looks bright for these fascinating cats.

A paraphyletic grouping including all five members of the genus Panthera, and the single-species genera Acinonyx and Puma.

Although there’s some more updated information for tigers showing rising populations, it’s quite possible puma populations are increasing too, and several subpopulations of lions are seeing localized increase, as we’ll discuss in the body of this article.

The Asiatic lion population is a special case. Once ranging across the Middle East and India, they were pushed to the brink of extinction by intense hunting, and are now found only in and around India’s Gir Forest in the state of Gujarat. With strong protection, they’ve since made a great comeback, rising from 180 individuals to 1974 to 411 in 2010. A 2017 census found nearly 650 wild Asiatic lions!

But there is a strange sequel to this conservation success story. When you have a rapidly growing population of an at-risk species confined to a small area, the logical thing to do is take a few and reintroduce them somewhere else; there’s more room to expand and less dependency on one site. India indeed has tried to do this, but was blocked by bureaucratic obstinacy. The state of Gujarat is currently defying an order from the Supreme Court of India by refusing to cooperate with lion reintroduction efforts, as they want to remain the only place in the world to see wild Asiatic lions. This is why cheetahs ended up being introduced in India’s Kuno National Park, which had originally been planned to be a new site for Asiatic lions.

The 10 tiger range countries are currently Russia, China, Nepal, Bhutan, India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

Want to know how to tell apart jaguars and leopards, two spotted big cats which can look very similar at first glance? Jaguars have a little black spot at the center of each of their rosettes, leopards don’t. (Jaguars are also bigger, stockier, behave differently, and live on different continents, but that’s harder to tell at first glance of a photo).

No, they’re not a variety or subspecies of leopards! It kind of sounds like they should be based on the name, but they’re actually a completely independent species more closely related to tigers. The older English word ounce for snow leopards seems more suitable. While we’re on the topic of big cat-related linguistic misinformation, “panther” is a generic term for a big cat that can apply to any species (especially those in the genus Panthera, but it’s also a common term for pumas), not a species name. “Black panther” is also not a species name; it simply means any big cat born with a melanistic allele giving them a black coat-this can happen in leopards and jaguars. Marvel’s Black Panther character is presumably named after melanistic leopards in Africa.

They’re kind of the opposite of super-adaptable big cat species like leopards and pumas that can range from deserts to jungles to snow-covered forests. Snow leopards exclusively use mountain habitat, with their beautiful gray-white coats giving them camouflage in rocky landscapes.

The Asiatic cheetah subpopulation has drawn a particularly rough hand; they all live in Iran, and the ultra-paranoid Iranian government has taken to brutally imprisoning cheetah researchers on trumped-up charges of spying, so they’re not getting anything like the help they need. The fact that they live in Iran is also why the Indian reintroduction effort had to use African cheetahs. With just 12 left and little chance of coordinated conservation efforts in modern Iran, they’re sadly quite likely to go extinct in the near future-but there’s still hope for the species in Africa.

What is up with this cat’s name?! The civilized world can’t seem to agree. The IUCN calls them pumas, Wikipedia calls them cougars, at least one prominent scientist studying them calls them mountain lions. The Weekly Anthropocene is going with “pumas” in this article since that’s in the scientific name, but has used “cougars” in the past.

The “Florida panther” subpopulation of a few hundred isolated pumas in the Florida Everglades is another special case: living hundreds of miles away from other pumas, they’re suffering from serious genetic diversity issues, and conservationists periodically introduce pumas from the Western US to keep them going.

I hope they find a way to keep the population of snow leopards, white tigers, white lions alive somehow, those are real angels lol, anyways keep up the good work SAM, you just earned yourself a subscriber, i like it the article, it dives deep into their history, talks about their population. i have one feedback though, you should have written like a list of questions like a list of questions on how we can save these populations and why saving them is important

Great reporting. I really worry about animal populations being at risk of being driven to extinction by east Asian beliefs in unproven health benefits from consuming various meats and horns, of wild animals. One of the unsavory aspects of the Anthropocene. Trust in folk remedies is very hard to eradicate, even in the 21st century