Unpaywalled Book Review: A City on Mars by Kelly and Zach Weinersmith

An absolutely brilliant instant classic on space settlement science, law, economics, ecosystem design, and more!

A book with the title A City on Mars sounds like it should be a classic Golden Age of Science Fiction-style paean to space settlement, and the authors (the polymathic power couple Kelly and Zach Weinersmith) acknowledge that that’s exactly what they originally hoped to write. However, after copious research, they ended a book that firmly convinced me that there will not, in fact, be a city on Mars in this writer’s lifetime (barring serious life extension technology, which I’m still hoping for). That sounds sad, but A City on Mars also convinced me that this is probably counterintuitively a good thing for right now, and there are lots of really cool things we can do in the near term to make it possible for future generations!

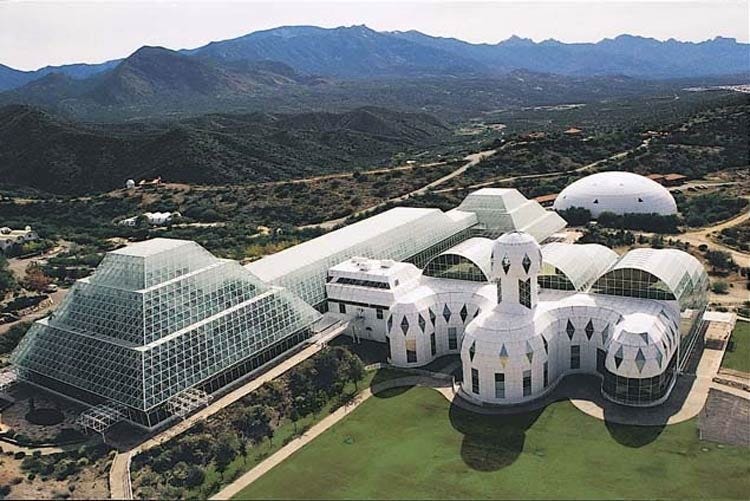

For example, one of the most interesting points explored in A City on Mars is the need for much, much more research in ecosystem design if we want to settle space, particularly if we want to go as far as Mars. The Biosphere 2 experiment in the 1990s (described in the book as “contrary to legend, not an unmitigated calamity”) remains the only serious effort at constructing a sealed self-sufficient ecosystem capable of supporting a human population, and it didn’t go super well. As A City on Mars points out, if we really wanted to create similar environments in space, we’d have hundreds such terrestrial biospheres, of various sizes, A/B testing species mixes and agricultural methods and air scrubbers and everything we might need to stay alive on other worlds. We as a civilization are manifestly not doing that, even though it would bring valuable ecosystem knowledge that would likely be really helpful on Earth as well. Why is this? The authors suspect it’s because ecosystem design doesn’t bring as much geopolitical, military, or reputational clout as rocketry, despite its arguably equal importance for the future of humanity in space. For everyone from heads of state to eccentric billionaires to the average taxpayer, “blasting humans in a rocket to the Moon is substantially more impressive than creating detailed reports about how to turn poop and food scraps into wheat.”

Full review now unpaywalled!

The Weinersmiths also go in-depth on the fact that we know almost nothing about how primates could safely reproduce or raise children in space. After an in-depth look at what we know of the health risks (bones demineralizing in microgravity, cosmic radiation damage, fluid retention shifts, etc.) they come to the conclusion that an artificial womb in extra-thick radiation shielding spinning in a gravity-simulating centrifuge would probably be the least weird option for successful space pregnancy. (Artificial womb technology would be amazing for a bunch of other reasons, notably that pregnancy and birth carry a host of health risks; about 300,000 people die in childbirth worldwide each year).

There’s a whole section on space law, primarily focusing on the Outer Space Treaty (which forbids territorial claims on non-Earth worlds, although resource exploitation is OK and there are some possible loopholes) and its closest Earthly counterparts, the Antarctic Treaty and UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Existing space law often gets handwaved away in discussions of future space settlements but would definitely be a top concern for any government or corporation trying to build one. As the authors write, “We cannot tell you how many times a space enthusiast has told us that space law is stupid because all law will go out the window the moment something valuable shows up on the Moon or Mars or wherever. If they believe that, they need to explain why it didn’t happen in Antarctica, where there is at least some evidence of valuable metals that would be far easier to extract and sell than anything on the Moon.” This quote segues nicely into another topic, space economics, which can be summed up as “it’s always going to be cheaper on Earth, or if in must be in space, in Earth orbit.” After reading A City on Mars, I am convinced that there is almost no chance of economically extracting commodities from the Moon or Mars to sell to Earth: from heavy metals to helium-3, anything you can painstakingly bake out of regolith can be mined or synthesized on Earth for a fraction of the price.

And then there’s the existential risk argument, beloved of Elon Musk among others, and somewhat convincing to this author until reading this book. The argument goes: no matter how hard and expensive it is to set up a society in space, it’s worth it because it would reduce the risk of human extinction if something bad happens on Earth. The authors spend a lot of time raising tough questions about this, starting with “setting up a society in space would probably cause whole new sources of existential risk.”

To start with, plain old geopolitics. It’s generally agreed that the “best” parts of the moon are the Peaks of Eternal Light and the Craters of Eternal Darkness, dramatically named regions near the poles where the mountains are high-enough to be near-constantly in sunlight (great for solar power), and the craters in their shadow stay cool enough to retain water ice. Sounds great for a settlement! But the thing is, this is a really small area of the Moon, smaller than the central European statelet of Liechtenstein. And that crater water is a lot by the standard of the desert-like Moon, but the authors calculated that “the total amount of water hidden in Eternal Darkness may be roughly equivalent to 10 percent of the volume of Sardis Lake. You know, Sardis Lake? A manmade lake in Mississippi? We hadn’t heard of it either, but it looks nice.” So if the Outer Space Treaty goes south or is ignored, there might end up being conflict over the best places to site a space settlement, a “scramble for the Moon.”

Honestly, this reviewer isn’t entirely convinced by the “scramble for space = war risk” argument. If the U.S. and China go to war, it’ll be over Taiwan, not Shackleton Crater. Based on this reviewer’s amateur understanding of history, great powers often posture and bluster and threaten war over faraway outposts, from Ferdinandea to the Fashoda Incident to the farrago of overlapping claims to Antarctica, but generally only actually go to war once core interests are threatened, once someone mobilizes troops on your border or bombs Pearl Harbor or something. Faraway not-economically-valuable places tend not to start wars.

However, this reviewer is convinced by another x-risk argument. Even if everything works perfectly, your victory condition-a self-sustaining space settlement-brings an unprecedented new apocalypse threat all its own. What you’d have just done, as the authors discuss in depth, is create a society of humans who are not dependent on Earth for their survival. And presumably have space travel, which for gravity-well reasons makes them essentially equivalent to a nuclear power right off the bat. Even the most frothingly crazed of dictators knows that if they used nuclear, chemical, or biological weapons, they still have to live on the same planet afterwards. A hypothetical “North Korea in space” wouldn’t, and essentially any self-sustaining space settlement would probably have the technology to nudge a whole bunch of asteroids our way. This isn’t quite as bad as it sounds, since space settlements would also be incredibly vulnerable to attack: a nuclear bomb-caused EMP taking out electronics would be nasty on Earth, but lethal in space. Still, “don’t worry, we’ll just have a brand new flavor of Mutually Assured Destruction” doesn’t exactly bolster the case that settling space would reduce existential risk to humanity.

The overriding theme of A City on Mars, painstakingly demonstrated in every realm from power generation to obstetrics to rare mineral mining, is that Earth is just better. Even on its worst day, even if climate change goes as bad as it could possibly go, even after a Deccan Traps-level continental flood basalt supervolcano eruption or nuclear winter or a bioengineered pandemic or end-Permian-level ocean acidification or a dinosaur-killer-sized asteroid impact or all of the above at once, Earth will still have the gravity we evolved with and a magnetosphere to protect us from cosmic radiation, which nowhere else in the solar system does. Unless we’ve somehow really really screwed up, it’ll probably still have a breathable atmosphere and drinkable water. An utterly nightmarish post-apocalyptic Earth would still be more habitable in almost any conceivable domain than the Moon or Mars. As the authors piquantly put it, for the foreseeable future our home planet will remain the only place where you can run around outside naked for ten minutes and still be alive at the end. Even if some unthinkable horror happened and that was no longer the case, even if we somehow managed to screw up the molten iron currents of the outer core badly enough to disrupt the magnetosphere (which we are nowhere close to possibly being able to do), Earth’s gravity alone would still make it the best place to build a radiation-shielded “bubble ecosystem” settlement.

Pretty much any argument for settling the moon or Mars (it’d be cool, we’d learn valuable things, new land to build new cities and try new societies, sealed backup copy of civilization in case of global disasters) also applies to Antarctica, the bottom of the sea, or a borehole deep underground. In fact it would be much easier to settle any of those places, and a heck of a lot easier to go back home if it doesn’t work out. If we were in some kind of sci-fi scenario where we absolutely had to build self-sustaining space settlements right now, we probably could eventually, with much labor and effort and resource expenditure and probably lives lost in failed attempts, but we don’t have to.

And yet…space! Space is awesome! Space is uniquely cool; it’s the entire rest of the universe! Screw the economics, there’s amazing cosmic vistas of knowledge and adventure to explore! For science, and the unconquerable human spirit! Even after reading a systematic dismantling of the technical, political, economic, and existential risk arguments for developing space settlements, this writer still feels that it’s just an intrinsically deeply desirable thing to do and really hopes humanity does it someday. And the authors of the systematic dismantling do as well. They ultimately compare space settlements to building a cathedral: at some point you just have to go with “faith” and/or “because it’s really cool” as a justification. Ultimately, the Weinersmiths recommend a “wait and go big” approach for space settlements, in which human civilization takes a while to develop really really good rocketry, robotics, orbital asteroid defenses of some sort, gravity-simulating centrifuges, and sealed ecosystem design, plus an agreed-upon international legal framework for sharing scarce space resources like lunar water, and then try to build permanent settlements on the Moon and Mars. They expand on the classic Konstantin Tsiolkovsky quote “The Earth is the cradle of humanity, but we are not meant to stay in the cradle for ever” to point out that right after the cradle stage comes the toddler stage, and toddlers are prone to almost accidentally killing themselves and need lots of supervision. This is pretty unpopular in the space-enthusiast community because “wait and go big” probably means “wait for decades if not centuries” and it would be really cool to see people living on Mars or the Moon in our lifetimes.

However, reading A City on Mars, and realizing just how hostile an environment space is and just how much human ingenuity it takes to do anything there, let alone live there permanently, brings back a lot of the wonder to the smaller steps we can take in space before that. “Wait and go big” for space settlement doesn’t preclude amazing advances in space exploration and utilization, which have already begun. Robot probes galore, the magnificent James Webb Space Telescope and its envisioned successors, internet and earth-observation satellites in low-Earth orbit, space stations and space tourism, advanced drug manufacturing in zero-gravity, hopefully soon a return visit to the Moon and perhaps even an out-and-back trip to Mars…all of this would be amazing. The early twentieth century saw an unparalleled hyper-acceleration in transportation technology: we went from the first heavier-than-air flight with the Wright Brothers in 1903 to landing on the moon in 1969, a mere sixty-six years apart with two world wars and the start of a nuclear-armed cold war in between! That is insane. The epic science fiction produced during this period ingrained a sort of cultural expectation that we would shortly have space settlements, followed by prolonged disappointment when we preferred not to. But really, we’re a species of aspirational savannah ape that’s sending robot probes to Pluto, tourists to orbit, and astronauts around the Moon again, and we’re on the point of getting really good extra-large reusable rockets! We’re doing great on space already, and there’s a lot of amazing exploration and research to be done. Even a temporary research base in a lunar lava tube would be an incredible achievement for humanity! We can leave full settlement as an adventure for the 2100s.

The precis above conveys some of the book’s main arguments pretty well, but you really need a few more direct quotes to get a sense of the delightful writing style. Here they are:

“Historically people have been willing to endure all sorts of hardships in exchange for a return on investment or eternal fame. Eternal fame is a substance with diminishing returns, so here we’ll focus on commodities.”

“Noting that you can make photovoltaics from metals and silicon is kind of like noting that you can build an airplane because the dirt below your lawn contains aluminum, iron, and carbon.”

“That Earth still has a breathable atmosphere, a magnetosphere to protect against radiation, and quite possibly still has McDonald’s breakfast.”

“This is substantially better than baking water out of stone or fighting Jeff Bezos for a frozen lake of ammoniated H2O.”

“On the plus side, partial gravity will restore the traditional relationship of humanity to waste, in which once it leaves the body it does not fly.”

“Salty, zesty taco sauce is so beloved by astronauts that for about a week in 1991 it became the first form of currency specific to outer space.”

“They weren’t quite a cult, but they were at least, let’s say, cult-adjacent.”

“Humans are squishy and weak. The real estate options are toxic. And pointy. And cold.”

“A common response to this concern is to shout ‘Robots! By God, robots!’ We like robots, but are skeptical.”

“Roughly speaking, for every two kilograms of plutonium, you get enough electric power to run a laptop. This is the most intimidating way to do word processing, but not terribly efficient…”

“This is entirely reasonable for a field like law, which is ultimately about the opinions and behavior of talking apes wearing clothes.”

“Under this interpretation, although a space miner can’t claim sovereignty over a giant asteroid, they could cut it into pieces and sell them at Walmart.”

“We sincerely doubt the UN is going to offer a seat at the table to a 0.1-square-meter hard drive owned by an internet-based parliament whose stated goals include routing around widely accepted international treaties.”

“Setting aside how everyone would feel about it, dangling a gun above Earth seems like it ought to be a strong military move. Analysts aren’t so sure.”

So: check out A City on Mars! It’s one of the most fundamentally interesting, compulsively readable, and laugh-out-loud funny science books this author has read in some time. A true instant classic and a model of accessibly and engaging communicating about complex issues. READ THIS BOOK!

Sounds like a must-read! But we need to think outside the current technology box. 1. Why colonize at all? Robotic probes with only marginally better shielding and instrumentation will send back near perfect visuals to us here as if we were walking on or flying over the surface of different planets and moons in person (gas giants excepted.). So much for tourism! Robotic factories with rail guns can do resource extraction and shipment to collection points in earth orbit or even to giant robotic manufacturies on the moon or Mars. No need to send humans into space..just to keep them alive for prolonged periods is both hideously difficult and expensive. So that's one future..human colonization and exploitation of system resources via robotic means. Very exciting.

The other future is even more exciting. We go out in person and dothe same things. Impossible right now, but not for long. Our advanced in bio-engineering are coming arriving at an astoundingly fast clip and thecdayvis coming, very soon in fact, when we will be able to bio-engineer ourselves into forms capable of prolonged survival, even conceivably outdoors, in environments like Mars. We will have our cities on Mars and walk outdoors in them!

I like both options and the way the future will likely unfold (if we're given the time) will be a mix of both. But in the long run in terms of getting all our eggs out of one basket, is the bio engineering approach. No reason a human can't be small or covered by something other than skin!

I think we should work harder to save this planet before we attempt to destroy another… sorry « but its cool » is really lame