The Weekly Anthropocene Reviews: The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson

A The Weekly Anthropocene Book Review

The Weekly Anthropocene published a review of Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future in November 2020. The interview is now republished (with a few text & image updates) for Substack!

Kim Stanley Robinson is perhaps the greatest modern utopian, a sci-fi and ecology writer extraordinaire.

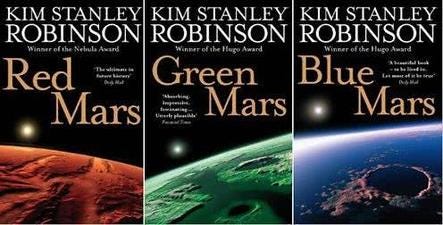

If you aren’t already acquainted with Robinson’s classic Red Mars, Green Mars, Blue Mars terraformation trilogy, his unique take on interstellar travel in Aurora, or the truly epic solar system-spanning 2312, do yourself a favor and borrow them from your local library. Robinson writes powerful sagas rooted in real-world science, populated by unique and memorable characters, and driven by strangely plausible events, all coming together to create futuristic worlds that one might actually want to live in. Reading one of his works is never less than a delight.

In short, when I received a review copy of Robinson’s latest oeuvre in 2020, expectations were high. And yet The Ministry for the Future exceeded them handily, and blew my mind into the bargain.

The Ministry of the Future, put simply, follows the eponymous fictional intergovernmental agency (created at a UN climate change conference in the mid-2020s) and their efforts to halt and eventually reverse catastrophic climate change. The novel takes that simple, almost bureaucratic-sounding premise, and turns it into nothing less than a future history of the 21st century, a civilization and biosphere-spanning saga on how we could manage to create a good Anthropocene after all.

Half of The Ministry for the Future is deeply rooted in concepts I’ve written about in The Weekly Anthropocene, like responsible geoengineering, targeted rewilding, the rights-of-nature movement, and Paris Agreement commitments. The other half is rooted in things that I wish I had written about, from the role central banks could play in tackling the climate crisis to the unique agricultural and governmental systems of the Indian states of Sikkim and Kerala. This book spoke to the deeps in me. It’s the sort of book I would have liked to write if I were a novelistic genius like Kim Stanley Robinson.

With so many weighty topics, it would have been easy for this book to be dry or textbook-like. But every page holds the reader’s interest, and most are positively entrancing. In addition to the chapters focusing on the story’s main characters at the Ministry, there are chapters narrated from the perspectives of a photon, a carbon atom, history, the market, and Earth’s herbivores. There’s a chapter that consists entirely of the roll-call at a future international meeting of rewilding groups (half the groups on the list I recognized as already existing!). There are chapters from the perspective of a climate refugee in a camp in Switzerland, a US Navy sailor, an Indian fighter pilot on an unprecedented new mission, people freed from slavery in African mines and Pacific fishing fleets, an impoverished woman farmer in a developing country, an oblivious and entitled one-percenter at Davos, and so much more. And, in a truly brilliant stroke, all of these chapters are written in the first person, creating a kaleidoscopic shifting narrative that underscores the fundamental unity of lifeforms on Earth with each other and the universe.

Robinson is also comfortable with impressive tonal and genre shifts. One of the early chapters, describing a horrifically plausible massive and deadly heat wave in India in 2025, is an exercise in visceral horror, with emotionally evocative devastation reminiscent of Stephen King’s The Stand. One of the later chapters, depicting a continent-spanning travelogue, seemed to me almost like a modernized and decolonized take on Jules Verne’s Five Weeks in a Balloon, exploring the wonder and majesty of Earth’s landscapes. The subplot at the refugee camp near the Ministry headquarters in Zurich (a city I now very much want to visit, by the way) reminded me of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis.

The only nitpicks I have are themselves illustrative of the depth, complexity, and awe-inspiring scope of the book. For example, I think Mr. Robinson is a tad pessimistic on renewable energy, and that the global market will move away from fossil fuels faster than he gives it credit for. The rapid and accelerating growth of renewables in the years since 2020 seems to bear this out. Furthermore, Mr. Robinson had no way of foreseeing the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which led the European Union to speed up their decarbonization efforts substantially. The ecoterrorist group in the book, the Children of Kali, is used as a tool to pose critical ethical questions in the grand tradition of authors like Edward Abbey, but also seems to be immune from societal backlash. And the Arctic Ice Project is currently developing a responsible geoengineering option for the Arctic that I think would work better than the one in the book. However, this is all still fascinating to read about.

In sum, this book is superb. It’s enjoyable on many levels: as a thrilling, powerful novel to lose yourself in for a while, as a thoughtful and imaginative look at what the rest of all our lives may be like, and as a subversively hopeful take on the climate crisis. Read this book as a gift for yourself and the people you love.

Have read them. 🙂 Wonderful trilogy! Adrian Tchaikovsky's Children of Ruin series is also worth review and reading!

Already on my reading list. Thank for this in-depth review.