The Weekly Anthropocene Interviews: Yaw, African Economics & Development Commentator

Yaw is a tech product manager & econ blogger. He is the author of Yaw's Brief: Guns, Trade, Cobalt & Africa Beyond Colonialism, a rapidly growing Substack on African development and economics.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Mr. Yaw’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

This interview is syndicated by both The Weekly Anthropocene and Your Daily Dose of Climate Hope.

What is your overall perspective on the African energy situation right now? As you know, renewables are taking off all over the world, but Africa remains the least electrified continent due to lack of availability of finance and a whole bunch of other stuff. Africa is also in a place where it's home to the to the majority of people who don't yet have access to basic electricity, so just basic energy access is much more of a priority than decarbonization. So what’s your take on renewable energy growth in Africa and the situation as it stands?

The way I like to think about this is in terms of how to evaluate this is to look at three things. One is the potential. Next is supply chain capacity. Third is financing.

When you look at renewable potential, you know, there's a lot of sunny and windy areas in Africa. There's a lot of places that have geothermal resources. Kenya right now gets most of its electricity from geothermal energy. There's a lot of potential!

The problem is just in the other two aspects that I mentioned, the supply chain capacity and the financing.

When we look at the supply chain capacity, if you're going to build a solar panel, you need platinum, you need manganese, you need a bunch of other minerals, and then you need to have the talent to be able to process these and be able to turn it into a solar panel. The resources are there. Most of the platinum in Africa is in South Africa, most of the cobalt is in Congo, and then most of the manganese is within a couple of countries like Ivory Coast, Ghana, and a couple other ones. But the problem is just the talent and the industrial capacity to process these and be making these panels. So I'm very bearish on the ability to get that local supply chain going.

And I think most of it will just be imported solar panels from Chinese companies. This is what I see. When I was in Ghana, my family's from Ghana, if you look at upper-middle class urban areas in Accra, the capital, like East Legon or Osu, you see a lot of rooftop solar panels and all of them are from Chinese companies. I'm not saying there's anything wrong with that! I'm just noticing that when it comes to where's the production or imports from, I just see a lot of it coming mainly from just importing it from Chinese firms, as opposed to being built locally. Will that change in the future? I'm not sure. Because I do hear about some African companies building solar panels.

There was an article about a solar factory opening in Ethiopia recently.

Yeah, in Ethiopia and also Morocco as well. There are bright spots of firms and factories being made. But I do think for the time being and for the near future, the vast majority will be just imported as opposed to being made in Africa.

And then the third part is the financing. I was reading in the Wall Street Journal that according to the IEA, solar investment in total is up to like 90 billion dollars in sub-Saharan Africa, and the continent needs around 200 billion. More than double.

The potential is there. The supply chain and the production is emerging, in the frontier phase. And the financing is an issue. So that's how I kind of look at that, from those three variables.

That sets up a lot of the more specific things I wanted to ask. Obviously local manufacturing capacity would be great, but importing from China brings a lot of benefits already. There's no fuel cost to a solar panel! Most of the value of a solar panel accrues to the person who buys it, not the person who sells it.

And I’m sure you saw the amazing news from Pakistan! Last year, Pakistan imported, like, 40% again of its entire electricity generating capacity in Chinese solar panels in like six months. And in South Africa, there's been a boom in like imported solar panels. China's got massive solar panel production now for its own domestic economic reasons. And I'm hoping that we can just move a lot of those to Africa and start getting people some electricity.

So what do you think, are any barriers left that are just blocking importing lots of Chinese solar panels? Is it just the cost, the disposable income? What do you think is the status of just the ability to import a whole bunch of solar panels from China? South Africa is doing that a little, but a lot of other places in Africa are not and could really use the electricity.

Yeah, there's a couple of big theories. You mentioned the biggest one, disposable income, and then second would be the industrial policy of some African countries specifically. Some of the African countries may be trying import-substitution industrialization.

What is import-substitution industrialization? Like, if Nigeria, let's say they wanted to make their own solar industry, they may put a wall of tariffs and they may subsidize their own solar panel companies, which basically makes it hard to buy Chinese solar panels. I'm not saying Nigeria is doing that specifically, but I guarantee you there's at least five, maybe ten African countries that have that kind of mindset. Like, “No, we need to make our own solar panels, let's take advantage of it ourselves” kind of thing.

America's doing exactly that with the Inflation Reduction Act and the tariffs on Chinese solar panels. Everyone's sort of trying to catch up to China on solar panels and get their own domestic industry going.

Totally, yeah. It's not just an African thing. It's a very global thing. Europe is also working on a subsidy strategy. Across the world, we're kind of seeing a going away from the rules of the World Trade Organization and more of just a national production strategy.

I can guarantee you that some African countries are pursuing that, because they’re pursuing that in so many different industries. That would be a barrier to just importing Chinese solar panels for energy.

So do you think that's a good idea? Do you think that it's worth it? Solar manufacturing is super, super competitive right now and African states do not have the resources to offer subsidies competitive with the US or EU, let alone China. Maybe better to not try to spin up a domestic solar industry and just import a bunch of Chinese solar panels to get electricity faster? Or do you think it's worth the opportunity cost to try to pursue that kind of industrial policy in Africa?

That’s a very good question. The thing is, African countries, in so many different examples, have tried import-substitution industrialization with, I would say, very meager levels of success. The first president of my country, Kwame Nkrumah, tried this before I was born. He tried it with gold refining, shoemaking, I think like 50 industries. A lot of them went bankrupt.

So it doesn’t have a good track record. In the grand scheme of things import-substitution industrialization is often good money chasing after bad. Empirically speaking, it hasn’t been successful in Africa.

But that doesn't necessarily mean you shouldn't pursue it. It has been incredibly successful in many other examples, right? When you think of Taiwan or South Korea, how their big enterprises became so big, government intervention was a huge part to get them to get to that scale.

Each African country will have to find their Goldilocks middle to see what makes sense for them. For a lot of countries, that probably looks like Namibia, which is sunny and windy and is getting a lot of support from Europe to try to build a lot of energy production in Namibia. I think the meeting in the middle between building domestic industry and importing everything is the best, like getting a lot of foreign investments. Namibia is a great example of that. Meeting in the middle, and just attracting a lot of foreign investments so that you can harness energy production. That I think is probably the best thing to do.

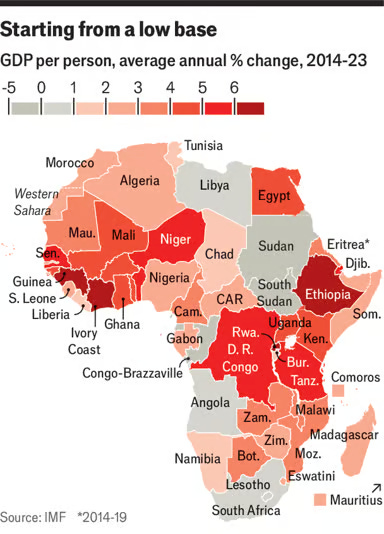

Fascinating. What countries do you think are rising stars in attracting foreign investment? I've been reading good things about Tanzania lately, about Ivory Coast. Economics Substacker Noah Smith hypothesizes that President Biden’s tariffs on Chinese and Southeast Asian solar products will help spread industrialization to other developing countries, potentially including some in Africa. There’s that new solar factory in Ethiopia being built with Japanese FDI that's specifically trying to make solar panels for the American market because they're exempt from tariffs on Chinese products. What other countries do you think have interesting prospects ahead of them?

I know which countries are getting the most FDI [foreign direct investment] in general, but then FDI specifically in solar or wind, I wouldn't have the ability to do that.

I’d love to hear just your general sense of the investment climate and the stability of government, your personal holistic assessment. You know a lot more about Africa than I do. Like, I'm not an expert, but I'm pretty sure the Central African Republic is not attracting a lot of foreign domestic investment. [Yaw laughs.] What's the opposite end of that scale? I know Morocco's built out a huge car manufacturing industry for Europe. What are some of the rising stars?

So in sub-Saharan Africa, I think if you look at the World Bank data on FDI flows, take inflows and subtract outflows, that's your net FDI inflows, there's only like 10-ish countries that get over a billion dollars of FDI, roughly, per year. South Africa, Ethiopia, Uganda, Mozambique, Democratic Republic of Congo, Namibia, Nigeria, Tanzania, Ghana, Guinea. And I think Kenya is sometimes another one. In terms of North Africa, they all routinely get over a billion dollars.

Other than that, the other sub-Saharan African countries don't even get one billion dollars. Sudan used to, but, you know, it's in a civil war.

Those are roughly the 10-ish sub-Saharan African countries that usually get over a billion dollars of net FDI at least per year.

In terms of North Africa, like Egypt, they all routinely get over one billion, with the exception of, I think, Libya, which as you know is in a little bit of stalemate right now.

I am surprised that the Democratic Republic of Congo gets more FDI than Kenya. I didn't know that.

Well, think of it this way. Congo's like double the size. And then, Congo has this state-owned enterprise is called Gécamines.

What happens is that Swiss or Chinese companies will form joint ventures with the Congolese government, with specific mines in order to dig minerals. So from China, CATL, the huge battery company, is one of the biggest investors in Congo. Another one is China Molybdenum, CMOC. The point is that Congo gets some foreign investment. But Congo getting $1 billion in investment is kind of nothing for a country that has over 100 million people.

One very small country, when I read the news about Africa, seems to be also becoming more and more of a foreign influence. I'm noticing more and more connections, sometimes really good, sometimes really bad, between Africa and the United Arab Emirates. On the negative side, obviously, they've been sending weapons to the horrific Civil War in Sudan. They appear to be running a massive, gigantic, illegal gold smuggling operation that's probably sucking away a huge chunk of the foreign exchange in much of the Sahel, which is awful.

But also, UAE companies like Masdar and DP World appear to be some of the major investors in building energy and infrastructure in Africa, which is really desperately needed. There's great good and great evil, so to speak.

And the Emiratis, that's just like 10 million people, most of whom aren't citizens. That's a very small country that is becoming a major player in Africa. What's your take on that?

There's a lot there. The UAE’s GDP, I think it's a half a trillion dollars or something crazy like that. [Almost exactly correct, Yaw nailed it]. That's bigger than most African countries, and they are just a small country.

UAE, depending on who you talk to, either has a very bad influence or very middling influence in the African continent. For example, a lot of African businesses will set up their subsidiaries or headquarters in Dubai. In general, from just African businessmen that I've met, people generally have good things to say about the country. There isn't, like, a feeling of ill will towards the country. But to the points that you were mentioning, yes, the UN has reports on UAE's influence in the Sudan war, potentially helping Hemedti and the RSF [and thus directly enabling genocidal war crimes]. There are talks about that. There are even reports about that, but UAE always denies it.

UAE has also provided swap lines to Ethiopia. So, Ethiopia was running out of foreign exchange. They literally defaulted on their loans in Christmas of 2023. They defaulted. And they literally had no foreign exchange left. They needed foreign exchange to import, you know, food, fertilizer, or fuel. The UAE providing swap lines to them, it helps keep Ethiopia fed, it gave Ethiopia the ability to keep the important food and fuel. And so, in that case, UAE's been a very strong influence. It's helped Ethiopia. Same with Egypt. Egypt running out of foreign currency. So as a result of that, UAE basically...

Didn't they essentially buy a port city in Egypt?

Exactly. It was for $35 billion. And that gave the Egyptian Central Bank just like $35 billion to continue importing bread and wheat and fuel. But it's not just there. UAE has been buying land, which has been providing a lot of foreign exchange, in a lot of African countries.

If you look at Middle Eastern Eye, and then you just type in the search bar “UAE,” you will see a bunch of land acquisitions that the UAE is doing throughout different African countries. And, you know, I view that as a very mixed thing. You can view that as bad in a sense.

I don't know if you saw my Sudan article, but I mentioned how [brutal former Sudanese dictator] Omar al-Bashir was selling his country’s land to Pakistan, to UAE, to Saudi Arabia. And the citizens literally lost their ability to have electricity and water, because Sudan didn't have great property rights, so it was very disruptive to a lot of people living there. That could be a big issue when it comes to a lot of these land acquisitions.

But at the same time, UAE is providing the central banks of these countries the ability to continue to import food, fertilizer, and fuel. So it's a two-way street. There are pros and cons of both these things.

So I try not to say that UAE is a total negative influence. I don't think it makes sense to say that, because UAE is a big trader. And in fact, if you look at the trade between UAE and all of Africa, UAE actually slightly ekes out the United States when it comes to imports. Part of that is the gold you spoke of. But still, I think it's a problem to say that UAE's influence is just straight up bad.

Yeah, it's complex. They've provided vital development assistance and they've also funded horrible criminality and war and stuff like that.

If you were talking to a person that was pro-UAE, they would probably say two things. One, they would say that UAE is only providing humanitarian assistance, which, you know, you could attack that claim. The second thing is that the UAE would say that they are trying to prevent Muslim Brotherhood-style ideology or something far more sinister from coming back to Sudan. Which has been big issue in Sudan for years. al-Bashir used to host Osama Bin Laden in his country! You could say that there's something valuable into trying to reduce that influence from being a destabilizing force. But obviously, genocide is bad. I’m not excusing that. It’s complicated.

Yeah.

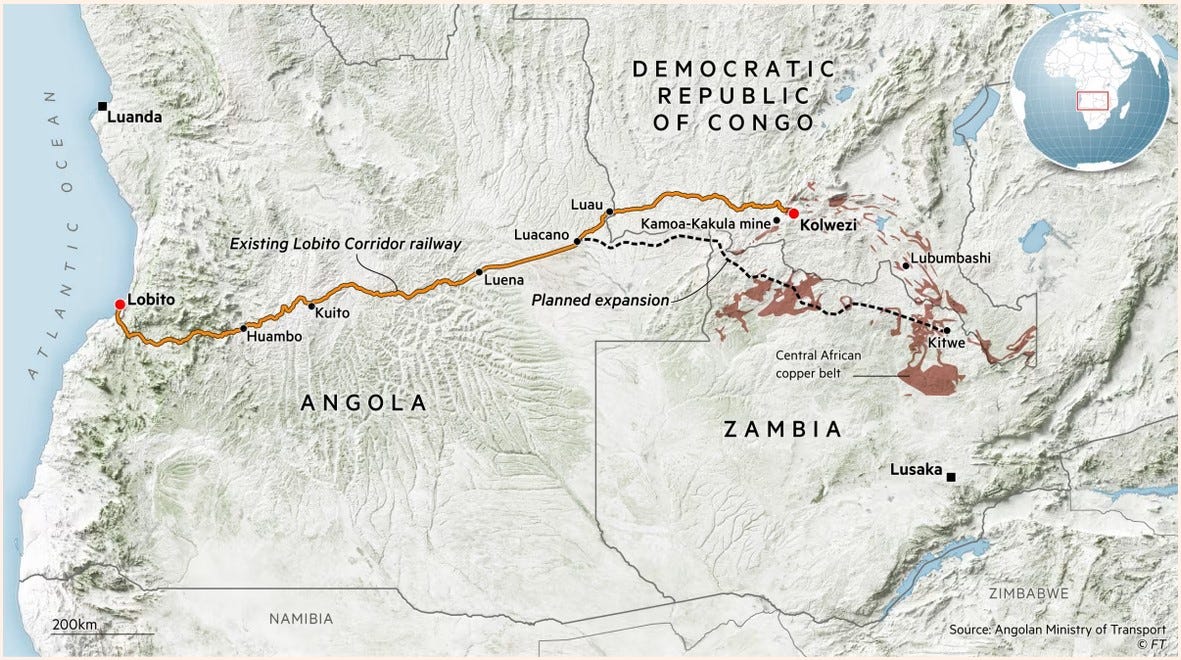

So we’ve talked about China and the UAE’s influence. There definitely seems to be a perception that the United States has fallen substantially behind in influence in Africa lately. And one major project that seems to be an attempt to turn that around is the Lobito Corridor in Congo, Zambia and Angola. Potentially soon the Simandou Liberty Corridor in Guinea and Liberia as well.

What's your take on the Lobito Corridor? Because it's not just the investment in the railway and the potential mining export. It's America’s flagship project in Africa, with a whole bunch of development assistance funding for solar farms and landmine removal and grain silos and a bunch more stuff along the path of the corridor.

I think it's a very, very great thing. The ability for Congo to export goods has been a very big issue for them for a very, very, very long time. If you looked at the UN statistics or if you just looked at the data from that MIT spinoff, the Observatory of Economic Complexity, what you would notice is that somehow Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi export in certain minerals, like gold or tantalum, more than the Democratic Republic of Congo. You’d maybe go like, what? This makes no sense. Because you know that the DRC has so many minerals resources. How could Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi export more in certain minerals than Congo does?

And that's because, obviously, there's a lot of smuggling and war and militias and whatever, but also because Congo can't easily export through its coast because its waters aren't fully navigable. There's a lot of rapids. It's not like the Mississippi River or the Danube in Europe, where it's kind of like a navigable water highway. That's not what the Congo River is at all. There's a lot of rapids. If a ship tried to go through it, it would be destroyed on the process of trying to navigate there. So what happens is that Congo sometimes uses Tanzania or Burundi or Rwanda in order to transit exports to the coast. The problem is that a lot of times those minerals get sold as Rwandan or Burundian or Tanzanian resources as opposed to Congolese.

With the Lobito Corridor, this will actually give Congo the ability to export its copper or its cobalt or whatever to another place and actually be stamped as a Congolese resource. That is a game changer for a country like the Democratic Republic of Congo. I also think this will help Angola become more of a transit hub for resources and gives it another place to get more revenue as opposed to just depending completely on oil and diamonds for export. Angola is probably the quintessential resource curse, Dutch disease type of country. And obviously it helps Zambia too.

So I think this is a great investment. I'm very happy that Joe Biden went there and physically was there to help sign this agreement. I think it's very great. I think the only issue is that the West is very slow when it comes to building up this stuff compared to China or Turkey. And due to that, America can do great things like this, but not at speed. I don't think we'll ever be able to compete on speed or just pure investment level. But this is definitely a fantastic project. And I'm very happy that the United States and the European Union led this to foster trade and transit facilitation and investments. So, yeah, it's a great idea.

Yeah, and it's really vital from a development point of view. It's going to hugely help those economies and directly, on the ground, help people's lives.

I'm kind of surprised that the U.S. climate community isn't paying more attention to it, because it is essentially a direct line from the Central African Mineral Belt, which is incredibly rich in critical minerals and getting richer as we find more stuff, to the Atlantic. And the inherent geography of it, it's a line going from the center of Africa to the Atlantic Ocean, not the Indian Ocean. So the geography favors export to America, not China.

Exactly!

And we're going to need so much copper. The IEA is projecting substantial increases in demand for copper due to electrification, copper wires. The Lobito Corridor could more or less solve that right there with that one project. There's so much copper in Zambia and the Congo. So this one huge effort could essentially be the source of most of the minerals needed to transition the world to a clean energy economy. I'm always surprised it isn't a bigger story.

Yeah, I'm surprised it's not a bigger story too. I think maybe because people just normally think of copper from Chile or something like that, maybe that's why.

But this is fantastic, you're right. Zambia and Congo are the copper belt and this will, the fact that it's going through the Atlantic Ocean, as you said. You know, great point basically.

One other thing I wanted to talk about is agricultural productivity. Dr. Hannah Ritchie has a great article that says, basically, increasing sub-Saharan agricultural productivity is one of the most important problems in the world in terms of potential benefits to humanity. Many of these countries are dependent on foreign exchange to import food, because their population's grown due to modern medicine but they don't quite have modern agriculture spun up yet. Fixing that would just be a really huge benefit for humanity. Also, people still dependent on subsistence agriculture without access to global supply chains are pretty much the most vulnerable to climate change, and most of them live in Africa.

So agricultural productivity across Africa really needs to increase. Some countries have done pretty well with that to start with, like Ethiopia. There's a lot of opportunity to grow. Morocco's leading a project on locally customized precision fertilizer application in Africa. There's the ICAT facility and its Artemis Project in Tanzania, using AI to breed climate-resilient crops. There's new crops. There's new apps. There's all sorts of stuff in this space. What's your sense of the promising opportunities for increasing agricultural productivity in sub-Saharan Africa?

Yeah, it's a very mixed story. I think we have to go further and see where the poor yields are coming from.

When we look at rice, for example, you'll see that Kenya is great at making rice. You'll see that India is great at making rice. You'll see that Rwanda is great at making rice. But then you'll see, you know, countries like Congo have like the worst tons per hectare in rice. Same with Chad or other countries.

So rice, you're starting to see a good amount of success in some pockets in Africa, which is great because Africans consume a lot of rice. A lot of their meals are very rice-based.

When you look at wheat, wheat is a sad story. A lot of African countries can't produce enough wheat for themselves at all. The only places that produce good yields for wheat are Zimbabwe, people don't really realize this, but they more or less basically recovered their yields from the Rhodesia era. Zambia also has decent wheat yields. Namibia and South Africa have decent wheat yields.

So the point is that you will see, if you go deeper, whether it's wheat or cassava or rice, you actually see some pockets of like really fantastic growth. But in general, agricultural productivity on the aggregate in Africa is truly terrible.

I think a lot of this has to do with property rights being really bad. Not having really important fertilizer. And also, a lot of agricultural schemes don't really work. In my country, Ghana, one of the military leaders had this thing called Operation Feed Yourself. It didn't work at all! What ended up happening was that North Ghana was about to starve! The World Food Program had to come in and provide food, because the scheme was so bad that yields fell. My mom told me about how it was the most terrible scheme ever.

I'm actually investigating this right now, I feel like I could answer this question better once I study a lot of the schemes that have failed and succeeded in different African countries. But yeah, that's my general vibe at the moment. They tried many schemes, but they haven't worked out very well.

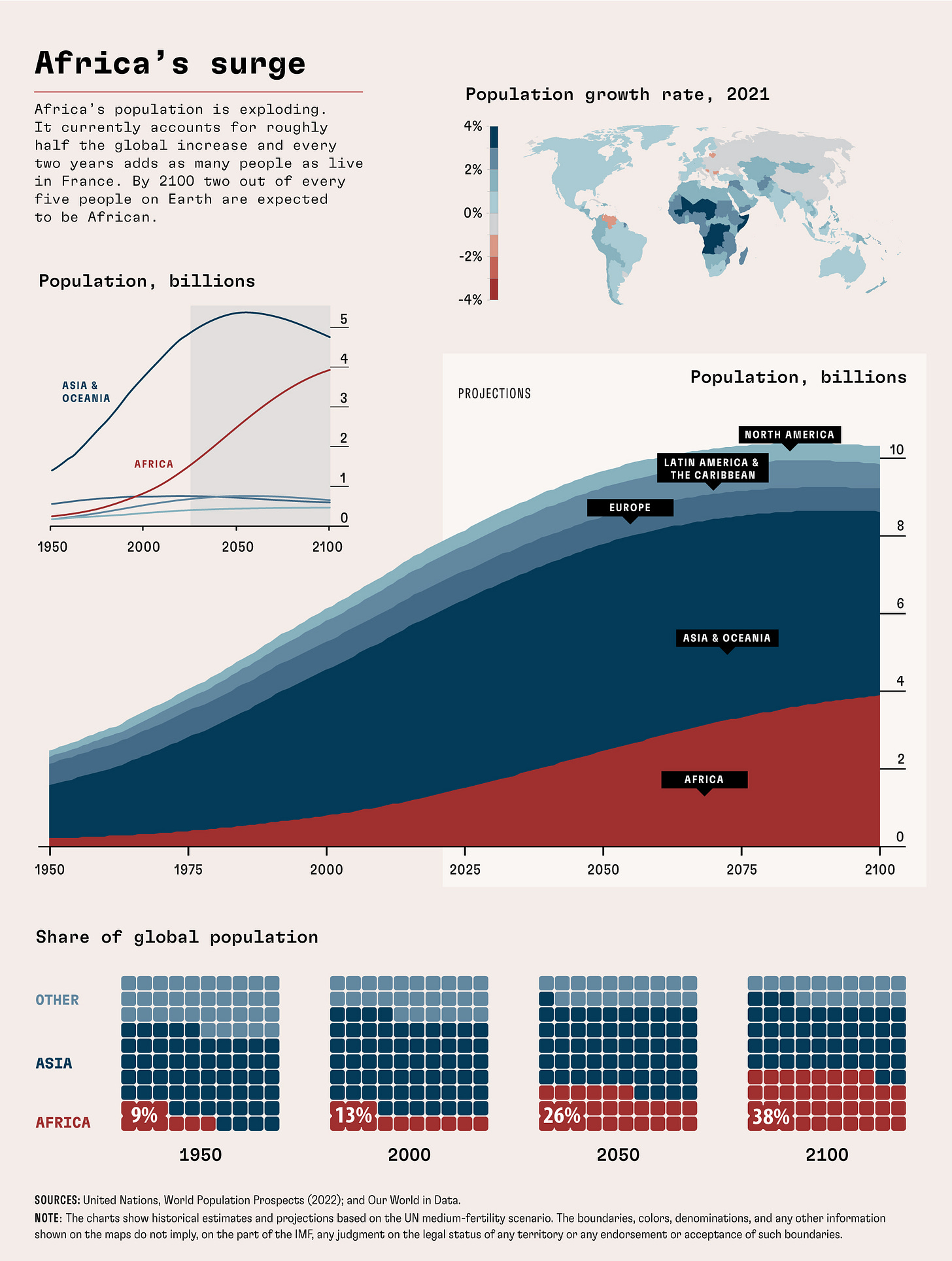

OK, so demographics. TFR in Africa is higher than most of the rest of the world, but it does appear to be declining sharply. What's your opinion on how demographics, the number of kids people have, plays into this development story?

Yeah, there's a couple things. First, birth rates are falling, even in Africa, but they're not falling as fast. What we're already seeing is vast migration in African countries. In fact, when you look at migration patterns, most Africans move to different African countries for opportunity. Only a small minority will try to go to Europe or some Western country or whatever. So what we see right now is that African economies are not producing enough jobs for Africans to work in. And as a result, that fuels the migration patterns that we're seeing.

People talk about Africa’s growing population like it's a great thing or whatever, but if you're not making enough jobs and if agricultural productivity is not growing fast enough, then it's actually creating more problems, you know what I mean?

You see a lot of people try to market it as a good story or a growth story. There are some positive aspects to it, but I think the negative aspects are already being realized right now. A slower birth rate, I think that would actually be a good thing.

You made a fascinating analogy recently comparing states currently dependent on fossil fuels with states historically dependent on the slave trade. I found it similar to the fossil fuel stranded assets problem. That's obviously a sensitive topic, but could you summarize your insights?

Yeah, yeah. The idea behind that was, I kind of see some of the Arab countries today the same as I saw African countries in the 1800s.

So I'm Ashanti, from Ghana. In Ghana, there are many tribes, and one of them used to be the Ashanti Empire. The Ashanti Empire, and many other African tribes and kingdoms, had deals with European countries to sell slaves. At the time, Europeans couldn't really enter the interior. They would die of malaria or sleeping sickness or whatever. So they relied on the African kingdoms to go round up war captives, prisoners from enemy tribes that they were in wars with, to send them as slaves to the Europeans. In return, Europeans would give them firearms or food or luxury clothes and things like that.

Now, this ended up creating a dependency. Slaves became the backbone of the agricultural economy for Europe: to sell more sugar or coffee or cotton, they needed African slaves to make that. And African kingdoms enriched their political elites, not the common people, by selling slaves.

We can kind of take that analogy into the modern day when it comes to oil. The raw material that's being sold, instead of slaves, it's oil. And in return, take France or Italy or America, what they give to Qatar or Saudi Arabia or UAE is modern goods, computers, semiconductor chips, cars, things like that. So what the analogy is basically talking about is, you know, when the British Empire banned the slave trade and basically told Portugal and all these other places to stop doing it, my ancestral king, the Ashanti king, basically was like, “This is a problem for us,” because he wanted to sell slaves from the enemy empires that he hated. This ended up destroying a lot of the economies that were super dependent on slave trading.

The region was incredibly unstable at that time. So many, such as the Oyo Empire, were worried that they were going to be enslaved by the Sokoto Caliphate, which like so many African empires were dependent on slaves for exports. They became more unstable because they weren't exporting enough to get firearms to protect themselves from enemies.

My argument, and it's a little bit of an exaggeration, is to say, oil could be like that. If we completely substitute oil with gas or more renewable energies, then a lot of these countries will run out of foreign currency, won’t have the ability to import necessary goods, won’t be able to fund their food and fuel subsidies that they provide to the populations. This is why diversification is the most important thing.

In the African empires, the ones that were more diversified were able to last a little bit longer. Dahomey lasted till 1894, because it was also selling a lot of palm oil. The Ashanti Empire was able to last until 1902 before being colonized because it also could sell, other cash crops or gold.

So that was showing the importance of economic diversification, which goes back to the modern day and why a lot of these Arab countries are trying to diversify as quickly as they can with stuff like their Vision 2030 projects. Basically it's a story about how depending on one commodity is really bad, and how you always need to diversify.

That does make a lot of sense. And indeed, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are diversifying really hard into solar and battery tech.

I recently saw an Economist article that really, really amazed me. A company called Aptech Africa, a startup from South Sudan of all places, has managed to build out a multinational solar installation business across 29 sub-Saharan African countries, often in very difficult business climates. [Here’s a library copy of the full article].

And, you know, Africa's more or less the sunniest place in the world, and they're just getting into renewables now that it's been perfected everywhere else. The most renewables-friendly region on Earth is only now starting to use renewables now that they've hit mass adoption and cheap mass production elsewhere!

I'm personally hoping that we can get a really fast sort of development miracle just due to energy inputs from solar panels, solar-powered irrigation pumps to help with agriculture, a whole bunch of other stuff.

What's your take on the bull case for renewable energy use in Africa?

Yeah, I think that I totally agree with you. There's nothing much more to add except the fact that, you know, the windiest and the sunniest places are in Africa. It's more usable there than it would be in a place like Germany, where it's barely windy or sunny.

And you're already seeing a little bit of a boom already in solar capacity! There's tons of Bloomberg articles and Financial Times articles. Solar boom in Nigeria, in Namibia, in Morocco, in South Africa. Morocco’s making so many solar farms! So I think the bull case is there. Solar and wind are getting cheaper. The ability to store energy even when it’s not windy or sunny is also increasing. So with all these technologies being in place, this could be the thing that catalyzes some sort of African boom!

It would be hard to come up with a technology that is more of a Swiss Army knife problem-solver for Africa than the solar panel, right?

Exactly, totally, yeah, yeah. Get more adoption of solar panels, and you'll see The Economist writing more articles of Africa rising again.

I'm really hoping! I write a steady trickle of articles about early solar development in Africa, because it’s just so important. If Africa can ever get anywhere close to India or China levels of solar build-out, that would just transform the world. That would just be such an incredible thing. And it would not only help solve climate change by preventing emissions, it would directly prevent a lot of the worst impacts of climate change hurting people, by giving people the energy needed to survive, the cooling or heating or light or power or irrigation pumps to survive a more chaotic world.

Yeah, it's incredible. You know, even in countries that are currently industrializing right now, like Vietnam, right? They're building more solar farms. They could be buying more oil or gas, but they're also trying to really ramp up on solar.

And this shows me the fact that, you know, it's not just some luxury good. These countries are thinking, no, we need this type of energy.

So the moment when that type of energy acquisition really flows to Africa as well, when it comes to solar and wind, it will do tremendous amounts of good for them in terms of these other downstream effects. Having energy means kids being able to read at home without having to walk far to do that! There's so many downstream effects, so many second order facts that can really increase by this so much. It's one of the things that gives me hope about the continent in general.

What can the rest of the world do to help that happen? Like, there's a lot of different questions.

Remittances are now substantially higher than foreign aid, and even FDI, worldwide. Does that mean that the best way to help Africa develop is just to employ African migrants and allow them to send money home?

There's a lot of questions about how foreign aid can end up misused by recipient governments. So would you advise more aid, or not? More targeted aid?

Would you advocate primarily increased foreign aid? Foreign commercial investment? Or simply employing African workers and hoping remittances allow Africa to import a lot of foreign tech? What are the major avenues by which you think we can accelerate that future and help solarize Africa?

I have an idea, and it’s a little unorthodox. I think Western countries should be more amenable to joint-venture technology transfer agreements with sub-Saharan African countries.

So what do I mean by that? It’s part of the reason that helped places like Taiwan or Japan or China industrialize. In order to invest in their countries — and we see this a lot with China — if you want to make a plant, if you want to sell goods to that population, you'd have to do a joint venture with a local company and give a license for that local company to manufacture the stuff you make within the local country. Generally, the American government really hates that when it comes to China [China has routinely copied American technology via this joint-venture setup] but there were more successes before when it came to Taiwan, South Korea and Japan.

Technology transfer is probably one of the biggest forms of industrial learning, learning by doing. If you form a joint venture with a local company, that Western company is basically teaching that African company skills. In addition to that, they have license that they can use to, like, help startups scale to grow. It does create more competition, but that industrial learning will help those countries make their own companies, make their own Western equivalents, and provide service, services and goods for their own people.

Because when you look at normal ways of how things are going, it's really not working. Remittances are only going to do so much. Foreign direct investment doesn't really transfer skills to the population, and it doesn't employ many people. You need to do more things to encourage more industrial knowledge, not just normal knowledge, but business-specific knowledge and learning by doing.

I think Western countries need to become more amenable to that, working with African countries.

Absolutely! I recently wrote about how America is helping fund a huge solar electrification effort in Burundi. That seems to be a really good project similar to what you’re talking about, as they’re closely partnering with a local African company, Weza Power.

Is there anything else you'd like to share?

Not much. I think one of the most important things when it comes to growth in Africa is thinking about that technology acquisition. I think I'll be writing a little bit more about how that historically happened in other countries and how that could work in Africa. So yeah, this is one thing I'm thinking about in African development.

Well, thank you so much. You're doing fascinating work.

Thank you.

Glad we did this chat! Happy to do another one whenever you'd like!

Great interview. Africa has such an upside potential for wind and solar development and America ignores the continent to its own loss.