The Weekly Anthropocene Interviews: Dr. Leslie Field, Glacier Reflectivity Enhancer

A Scientist Spotlight Interview

Dr. Leslie Field is a chemical, electrical, and industrial engineer, a professor of Engineering and Climate Change at Stanford University, and an inventor with 61 US patents with a cumulative economic impact of over $3 billion for her employers. She’s also the founder of the Bright Ice Initiative, working to prevent and slow climate change-driven ice melt by spreading a thin layer of reflective, nontoxic hollow glass microspheres over the ice to raise its albedo.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, and Dr. Field’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

Dr. Field’s Climate Awakening

Can you tell me about who you are and your journey to the climate change field, your original pivotal moment on climate change in 2006 and your subsequent invention?

Hi! It’s a pleasure to be here and talking about something that we both agree is awfully important. Climate change is, I’m convinced, the challenge that’s facing this generation. And I have kids in this generation, so I have my heart at stake.

I’ve been an engineer for a long time. I grew up loving science fiction. My ABCs were Asimov, Bradbury, and Clarke. These days, Kim Stanley Robinson, oh my gosh. You mention his Ministry for the Future at the AGU [American Geophysical Union], and people are all reading it. He actually guest lectured in my class last year. At any rate, growing up, I noticed that the interesting stories, the ones that really fill you with hope, are the ones where the main characters never give up. That’s what we’re gonna have to remember as climate change gets worse and worse. We may want to pivot how we’re thinking about things, try something different, but I think the worst thing we can do is continue to regard it as, “Well, it’s not going to affect me, it’s going to be in the future. It’s going to be somewhere else.” That’s not true. It’s way past time to take action.

“I think the worst thing we can do is continue to regard [climate change] as, “Well, it’s not going to affect me, it’s going to be in the future. It’s going to be somewhere else.” That’s not true. It’s way past time to take action.”

-Dr. Leslie Field

So my pivotal moment came after having grown up as someone who loves to think about how you could solve this problem or that problem, then industrial R&D jobs, and then my own consulting jobs when I needed the flexibility to raise kids. I’ve got more than 60 issued U.S. patents now, and some of them made some big impacts for my employers and my consulting clients. That gives you a certain amount of confidence that, you know, not everything that I think of is great, but some of it really is thoughtful.

I’ve always been a passionate environmentalist. The first Earth Day came about when I was in K-12, and that was a huge thing for me. I’ve been a Sierra Club member forever. Yosemite is one of my favorite places in the world. But with all that consciousness, seeing the Al Gore movie An Inconvenient Truth back in 2006 was quite the wake-up call. It was like, What? Is it that bad? How did I not know this? My kids were 6 and 10 at the time-how would this not affect them, even here in California? And it really, once you finally get it, that becomes top of mind. It’s like, oh my goodness. How did I miss this? How have I not been working on this all this time? What can I do?

And fortunately for me, that was a time during which I was a consultant, and I had become a consulting professor at Stanford. That allowed me to start connecting with professors working in the field. Steve Schneider and Terry Root were mentors for a bit. I got connected to a course they gave that first summer, when I was obsessing about what on Earth I could do. And at that point, I had already had an idea. I was just diligently, any spare minute, researching what are the really dire things that are happening. Is there something we can do about that?

Ice Reflectivity and How to Augment It

One of the tipping points that was very clear from Gore’s movie was that the loss of reflectivity from sea ice was a big, big deal. Especially Arctic sea ice. What we’ve had historically is this beautiful reflective shield in the Arctic of multi-year sea ice that could safely reflect sunlight away, all during the most sunny part of the year, the 24-hour-a-day summer sun shining on this ocean. Once that ice starts going away, instead of that very bright surface to reflect, you then have a darker and darker surface. First-year sea ice is much less reflective than multi-year. Multi-year is more imperfect, it’s thicker, there’s more surface area. You get more chances to reflect light away the older the sea ice gets. Increasingly, as you melt this ice over the summer, you’re getting open ocean, very dark, not very reflective at all. And you get thinner sea ice. We’re still lucky enough to be reforming sea ice in the winter (yay!) but more of it is first-year sea ice because it’s forming on open water rather than the previous inventory. And that’s a big, big feedback loop. A positive feedback loop, which does not mean that it’s driving us in any good direction. “Positive” in this context means that the more it happens, the faster it keeps happening. And that’s an accelerating feedback loop. It’s a huge effect, and that’s what I wanted to focus on.

I asked myself a question. After having looked at and read all kinds of stuff, I confirmed that this is a positive feedback loop, and it’s dire. I asked myself the question (this is the creative moment, I guess): Is there a safe reflective material that would help us replace that lost reflectivity in the Arctic? Is there something that could do that?

That was the question. And that’s something I’m going to be teaching my students this quarter. Frame a question that gets your brain into the details, like “well then, the kinds of materials are such and such, the characteristics it would need are this and that.” When you get into a wheelhouse that you understand, you have a prayer of creating a solution. Then the problem becomes finite, rather than “oh my god, the ice is melting.” You get to actually start creating a solution, which means testing things. Another part of that process is if you can figure out an inexpensive and quick way to test some of your assumptions with no hazard to anybody, that’s a very, very useful thing too.

“When you get into a wheelhouse that you understand, you have a prayer of creating a solution.”

-Dr. Leslie Field

So I got big blue buckets from our local Target and started filling them with water, putting materials on top, and seeing, does that keep the water cooler? Does that help? You can start figuring out what relevant sorting mechanisms there are to figure out what’s going to work and what’s not. As an experienced inventor, I’m not very shy about going ahead and doing something that might strike someone as ridiculous [laughs]. If you can do it quietly and inexpensively in your backyard, you can sort out some of the basics. There are all kinds of things you can try before you get to something that actually will work. That’s all valuable information. It’s not failure; it’s the opportunity to do more work and get more information.

“As an experienced inventor, I’m not very shy about going ahead and doing something that might strike someone as ridiculous.”

-Dr. Leslie Field

We finally found something that looked really good. Hollow glass microspheres are what we chose. We chose a material that’s in industrially widespread use for many, many applications. It’s made of silica, which is one of the most abundant materials on the planet. [Silica is generally the most common component of sand]. We all evolved with it. Every ecosystem has a bunch of silica in it. It’s in most of our rocks, in all the marine environments, dissolved and particulate and in the sediments. These silica-based hollow glass microspheres are engineered to be bright and to float. Which I like; I wanted something reflective and harmless.

We’ve done a lot of testing. We commissioned it through labs, they fed ridiculous amounts to small birds and a species of fish, and they were all fine afterward. It was these ridiculous amounts because you really want to test to see if there’s anything negative. They were all fine. There was one fish death, and it was in the control group, that is, the group that didn’t have anything fed to it at all. Nothing that got fed to them had any problems, which was good. So we were very, very careful.

“We’ve done a lot of testing. We commissioned it through labs, they fed ridiculous amounts [of hollow glass microspheres] to small birds and a species of fish, and they were all fine afterward.”

-Dr. Leslie Field

I’ve always been saying, from the beginning, that “first, do no harm” is really the thing that we should look as as we’re trying to look at interventions. And part of that was inspired by Steve Schneider, that epic climate scientist-no longer with us, unfortunately. He was great, and he was really taken with this idea. Steve Schneider and his wife Terry Root had a summer graduate course about climate change, and I asked for a meeting with them to describe what I was thinking of. And they were like, hey, that’s interesting. It was encouraging to have epic climate scientists like that really interested in my idea, which meant that I really had to pursue it!

Why not focus on CO2, which is the root cause of the problem? A lot of people are focusing on CO2. But what we see, tragically, is that even though people know we should be doing that, emissions are going up. [Although that may soon change: the International Energy Agency expects global CO2 emissions to peak and start going down in 2025 due to growing investment in renewables]. So if we wait for people to take that seriously and get that done, I’ve got enough industrial experience to see that even once we get really serious about it, it’s gonna take years to get that infrastructure turned over. You don’t just immediately say “we’ll cease all CO2-producing activities” because the entire economies of so many parts of the world are built on that. And that’s going to take time to rebuild. Transitioning over is not going to be instant.

And that’s why people like me think, what can we do in the meantime to try to slow down what climate change is doing to us? Destabilizing our weather, contributing to more climate refugees. Here in California, we’ve been in the third year of a massive drought, and then we’ve had these unprecedented atmospheric river storms coming through. A billion dollars in damage at least, is what I’ve been reading. [Here’s more on that story]. It’s here. For a long time, people had this complacent view that climate change would be in the future and be somewhere else. Maybe for a while, that was true. It’s not true anymore.

Test, Test, Test: Ideas to Reality

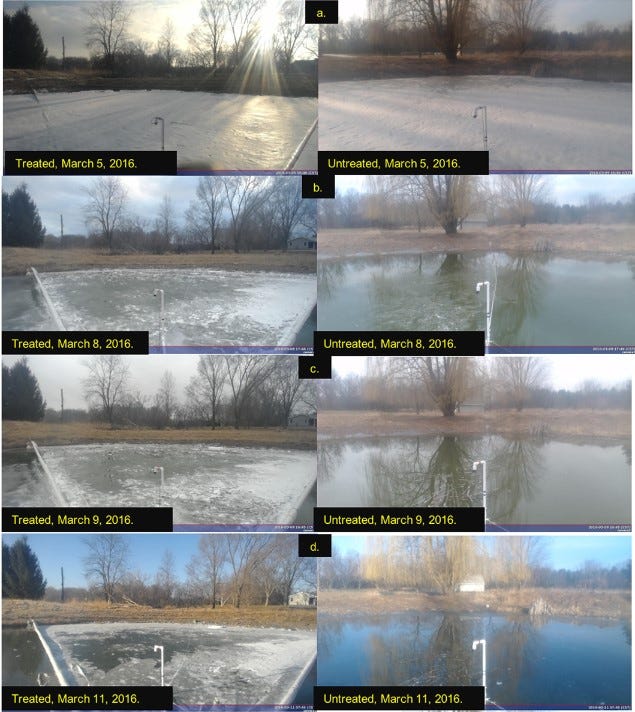

So that was the creative moment; I came up with a way to slow the ice melt. We’ve documented that over the years. And that’s what I focused on as a volunteer for many years. I started something called Ice911 Research, I began to get a team, and eventually got employed. That was important work. I’ve got a group of volunteers collaborating with me in Minnesota who have done phenomenal testing work on a self-contained pond. I’ve been getting messages lately from a few prominent organizations complimenting us on this latest paper that we put out, also in Earth’s Future, talking about the details of this pond work and a little bit about what that means for the world. [Here’s the paper: A Controlled Experiment of Surface Albedo Modification to Reduce Ice Melt].

We work on many fronts. You definitely need to be able to figure out: is it effective? Is it something that would actually help? Is it safe? If it’s not safe, it’s a non-starter. The fact that the kinds of materials we’re using have been manufactured by many companies all over the world and used in many applications, and have what is called a “clean MSDS,” (materials safety data sheet), so they’re not toxic at all, is key. I wanted to use a material that had several different manufacturers making it so that we wouldn’t be caught negotiating with somebody who could jack up the price. We don’t have that. We have a lot of competition in that field, which is great. And different variants of those materials, which is great. That was one aspect of it.

We’ve been testing that; we now have a thermodynamic model of that pond with these materials on it. It really worked very well.

From years of working in industry and consulting, I’ve learned a lot about what the frameworks need to be for these solutions. I’ve even co-convened at AGU meetings, town halls, and workshops on: what do we need to consider as we do this? I’ve been included now on a smallish panel where they try to get people who’ve been working in this areas to collaborate on updating the AGU stance on small-scale research solutions testing. It’s been neat, because it only adds to my framework considerations. You need to know who you’re solving for and who you’re solving with. If you can get active participation from the people who live there, that’s much better; they’re experts in these areas. And sometimes, I’ve learned this over time in consulting, people come to you with a stated problem, but it’s not really what they need solved. Once you have the right questions, you’re really far ahead.

I’m convinced that working as a nonprofit is the only way we’re ever going to get permission to work on sea ice, but we’ve still never gotten permission to work on sea ice. That’s what the International Maritime Organization down at their meeting in Chile told me. We went down and said, this is what we’d like to do. What do we have to do to satisfy the permissions and the rules? And what they told us was very sincerely, “We understand what you’re doing, but it’s going to take a long, long time to ever get permissions in international waters.”

The Iceland Test

This year our team will be conducting a collaborative research-scale field test of our approach on a glacier in Iceland, with fully documented permissions to do the work.

We’re testing on the Langjökull glacier in Iceland in August-September 2023. We’re hoping that our albedo enhancement will help it avoid the fate of Okjökull, which as you may know is an Icelandic glacier that has effectively entirely disappeared due to climate change. Our team in Minnesota has tested a material that we believe will stay in place better on glacial ice than the reflective spheres we concentrated on previously, based on a clay used widely in building applications.

For this year’s test in Iceland, we’re part of a terrific collaboration with our own US team, a team from the Icelandic Meteorological Office, and an expert environmental impact and water impact assessment from the Himalayas. An environmental expert will be guiding us on the environmental and water assessments in Iceland.

The 2024 Chhota Shigri Mission

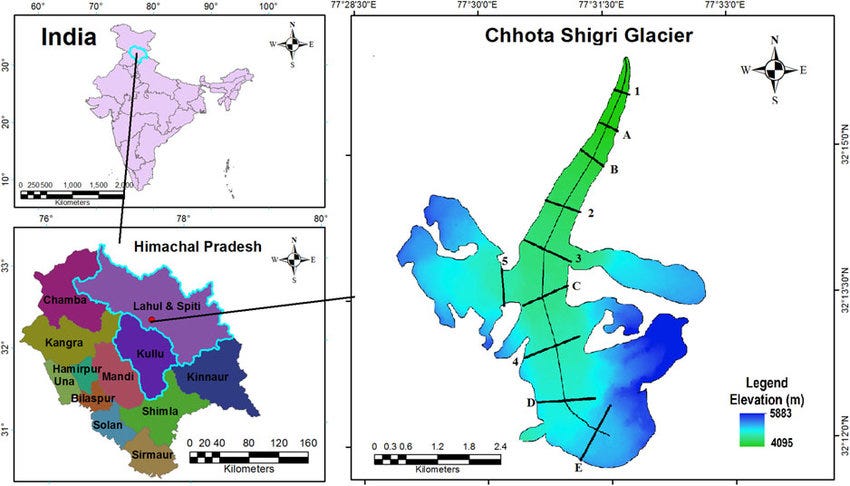

For 2024 we may need to do some follow-up testing in Iceland, and we have planned a research-scale field test on the well-studied Chhota Shigri Glacier in India, with an expert team including a prominent glaciologist from Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Indore and a Himalayan Indigenous environmental expert, as well as the Healthy Climate Initiative, India, and our own Bright Ice Initiative and Ice Conservation Engineers teams.

We’re still working out the Memorandum of Understanding necessary to conduct field tests on Chhota Shigri. Also, our previously tested microbeads would likely fall off this glacier’s slopes, so we’d be testing that new clay-based albedo enhancement.

When I got invited to work in the Himalayas to work on glacial ice, I was like, “That makes sense.” People are already feeling the effects there. You don’t have to prove to them that climate change and ice loss are bad. A third of Pakistan was flooded in 2022. People lost millions of homes. Thousands of people died. [At least 1,739 people were killed, including over 600 children, and over 2.1 million people were left homeless due to the climate change-driven 2022 Pakistan floods. Glacial melt was a significant contributor, along with heavier than usual monsoon rains.] And the risks are that as the melt in the Himalayas continues, we’re threatening the water supply of the hundreds of millions of people who live on the Indo-Gangetic Plateau. It’s another one of these positive feedback loops, like the multi-year ice. The more it melts, the faster it’ll keep going. It’s an accelerating feedback loop.

That glacial melt contributes to a couple of things. Yes, you’ve got more water flow for now, but it’s breaking dams, flooding people, and going to the ocean eventually. It’s not available in any predictable way for your crops for the rest of the year. So you end up in these flood-drought cycles with a lot of damage to people’s homes and livelihoods in the meantime. And a third of the world’s food supply comes from agriculture in that region. So it’s a pretty dire thing. If you’re having people losing their homes, their livelihoods, their food, and their water, it leads to tragic displacement and death. What kind of a world are we living in if we don’t do something about that? That’s where people with various climate interventional solutions come into play.

“If you’re having people losing their homes, their livelihoods, their food, and their water, it leads to tragic displacement and death. What kind of a world are we living in if we don’t do something about that? That’s where people with various climate interventional solutions come into play.”

-Dr. Leslie Field

Another one of the constraints was that I wanted something that deliberately was not global and was not going to engineer some large part of our ecosystem all at once. I deliberately chose something that was regional and localized. It’s on the surface; you can see right away: are we damaging something? You can test in a small area. The AGU is coming out with a new position paper that went out for comment, a new policy document on small-scale research testing. If you can do small research-scale testing, you can figure out what you’re doing. And if you do that at a small scale, you don’t have major risks to anything. I wanted something with very low risk factors.

“I wanted something that deliberately was not global and was not going to engineer some large part of our ecosystem all at once. I deliberately chose something that was regional and localized. It’s on the surface; you can see right away: are we damaging something? You can test in a small area.”

-Dr. Leslie Field

There are many metrics you’ve got to look at. Is it going to save lives, is it going to protect homes, is it going to perhaps even slow global temperature rise feedbacks? That’s important. Is it going to impact somebody somewhere else? That’s important to know too. Do you want the inventor to be making the decisions as to what is in the best interests of the world? Probably not. Our job, as I look at it, is we need to determine what actually are the outcomes of doing this, in a small research scale.

“There are many metrics you’ve got to look at.

Is it going to save lives, is it going to protect homes, is it going to perhaps even slow global temperature rise feedbacks? That’s important.

Is it going to impact somebody somewhere else? That’s important to know too.

Do you want the inventor to be making the decisions as to what is in the best interests of the world? Probably not.

Our job, as I look at it, is we need to determine what actually are the outcomes of doing this, in a small research scale.”

-Dr. Leslie Field

And then, with climate modeling, they can propose; what would it look like if it were bigger? But you can study that; you’re not doing that. You’re doing it on a small scale. I’ll say as an engineer, there are a few mantras I have, and one of them is: “In theory, there’s no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is.” My entire team agrees, it’s test, test, test. You’ve just got to test and figure it out.

“There are a few mantras I have, and one of them is: ‘In theory, there’s no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is.’ My entire team agrees, it’s test, test, test. You’ve just got to test and figure it out.”

-Dr Leslie Field

As a young engineer, way back when, in my first full-time job in a research lab, we had some experiments that would take overnight to line out and see what the results were. I walked in one morning, all confident, first job out of school, and the results were nothing like what I expected. I was like, oh my gosh, they’re going to fire me! I was wrong. They knew if you weren’t surprised sometimes, your research isn’t significant enough; it’s just testing what you already know. I spent the next few weeks digging into this. And the thing that’s really significant about that is that when you get surprised, and you inevitably will at some point, it’s because you’re about to learn something new if you keep at it and keep persevering. That’s an important thing. That’s one of those things I’m going to share with my Stanford class this year. Don’t be discouraged if you get something new-maybe it’s something totally new. Maybe it’s the thing we need. You’ve got to test things. You’re going to be surprised.

“When you get surprised, and you inevitably will at some point, it’s because you’re about to learn something new if you keep at it and keep persevering.”

-Dr. Leslie Field

There’s been debate over whether we could raise the funding in time to do the test at the Chhota Shigri Glacier, but basically we know we have to do it. This really is dire at this point. The time for complacency is past. A small-scale test like this isn’t going to do anything bad anywhere. We know that. We’ll be watching to see if there are any side effects, for the future. Everything you do, you’ve got to observe it like crazy.

So yes, in June, we’re collaborating with Dr. Farooq Azam, a glaciologist who has been to this particular glacier over thirty times, so he knows the history. This is a very well-documented glacier, Indian and French scientists have done collaborations on this. It’s well known. And it’s having unprecedented weather, as things change. Melts are going faster, temperatures are rising faster. And there’s lots more darkening. Glaciers around the world have been darkening, from their own silt underneath but also dust that gets blown in from other places. Even in glacial regions, you can find soot from wildfires there. Local cooking, and local pollution as people drive more to visit these glaciers before they’re gone. It’s an accelerating situation.

And so we’re going to be there. The solution that I’ve been working on for many years has been for flat sea ice. It works phenomenally on pond ice, where we’ve been testing it. But for glaciers, we’re dealing with slopes, and so we have things we need to determine there. The collaborators in Minnesota have figured out how to make some sloped ice, and they’ve been testing some other materials. I’ve been working on figuring out barriers to discourage losing our materials downhill, to retain the brightness longer. There’s a lot of pretesting we’re doing.

This will be the first year of what we’re planning to be three years of testing on the Chhota Shigri Glacier. I know from experience anywhere I’ve done any kind of testing, you’re going to learn a lot the first year that you did not expect. Carrying those lessons on, let’s be able to keep iterating the experiment until we really know what we’re doing and what is likely to be a good proposal going forward.

It’s not going to be that we arrive there and we say, “We shall save your glacier!” No. We’re going to run some tiny tests and see what works in these conditions. What conditions do we already know how to work on? If there’s a flat melt pond area, what we do should work very well there. Can we help with GLOF, which is a big problem there? That’s Glacial Lake Outburst Flooding, getting so much melt that the dams break, and it devastates everything downstream. Maybe we can help with that. We’re going to assess the situation; our climate modelers are very excited about this. So we’re trying to gather the momentum and the funding to be able to afford to do this small-scale field research work. Learn what we’re doing, get the climate modeling done. If we’re moving to any other materials, we’ve got to get those assessed again for safety. It’s exciting work. We’ve got to move ahead.

“It’s not going to be that we arrive there and we say, ‘We shall save your glacier!’ No. We’re going to run some tiny tests and see what works in these conditions.”

-Dr. Leslie Field

And then, Greenland. There are many places in the world that are melting and are going to have dire effects on sea level rise. Greenland is on the list. Some of our team just came back from a forum run by the Arctic Council, which has been just a terrific organization to work with. Three of our team went there, and they had a lot of substantive discussions with the ministers there from the concerned Arctic regions. I’m looking forward to hearing more about that. We haven’t negotiated permissions at all there, that’s much farther away. Because first, you need to have a consensus from the people who live there that they’d actually want you to work there. That step hasn’t happened yet. We think we can get some help with doing that from some prominent people. That’s the idea.

That is amazing. So are you spending all of summer 2024 on the glacier?

The scientist who’s most experienced there is Dr. Farooq Azam, from the most prominent scientific institute in India, IIT, the Indian Institute of Technology. It’s a big deal; we get to collaborate with experts! That’s pretty great. He’s proposing June as the time to get things placed. You know, you survey it, get your attempted solution. There’s always a test plot and a control plot, so you can compare if you actually slowed melt in this little region. By little regions, we’re talking about 10 meters by 10 meters, we’re really keeping things small. So 10 by 10-meter test area, 10 by 10-meter control area for each of the things we want to look at. He’s proposing that people go back-it won’t be the same team-several times during the year, for a total of three times.

There’ll be automated instrumentation there, which is one of the things we’ve done even on the pond in Minnesota. IIT has instrumentation that’s already in the field. But you still want live eyes, always, to go back midway through and see what you predicted the melt would be, the end of the melt, and so on. How long did we increase the ice in terms of visibility? How did we increase reflectivity? How much did the reflectivity increase? That’s essential information for climate modeling, which can tell us: Would this be a good idea in this region or not? We get to run a lot of “tests” virtually through computer modeling, but we have to always ground them in reality, in what our data says. You can’t fool yourself and go too far astray. Working in both realms, you get to keep yourself honest that way.

And we have a good laboratory now that we can work with on these kinds of materials for further testing, up in northern New Hampshire. It’s a really all-in effort everywhere.

As far as your readers, one of the questions that always should come up is, what can you do? Talk about climate change! Learn that it’s actually now, not a future problem. And if you’re interested in our work, check out the brighticeinitiative.org website, look at what we’re doing, and sign up for our mailing list if you want to get periodic updates. Spread the word. Not enough people realize just how bad it is and how much hope there is, all at the same time. A serious situation, but a lot of good work going on all around the world, various efforts to address various parts of the climate crisis.

“Not enough people realize just how bad it is and how much hope there is, all at the same time.”

-Dr. Leslie Field

Thank you so much!

Thank you.

She is very creative! And her generosity of spirit is admirable! Another great interview!