The Weekly Anthropocene Interviews: Dr. Dominique Bachelet, Climate Change Ecologist

A Scientist Spotlight Interview

Dr. Dominique Bachelet is a climate change scientist and ecologist with over 40 years of research experience. She is known for her research on fire, forests, and climate change in the Western US and worldwide, and more recently her innovative work creating geospatial visualization and analysis tools to respond to climate impacts.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Dr. Bachelet’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

Can you share your personal story and journey towards climate science?

I came to the US in 1979 to do my Ph.D. here. My advisor in Paris had done some modeling in Saskatchewan, and he told me that modeling groups in the US were more advanced than in France at the time. So I came here, and ended up with two advisors doing environmental interactions work in the Great Plains, in Colorado. I was looking at plant-animal interactions and how herbivory in particular was affecting plant physiology and morphology. I did a postdoc in California studying nitrogen fixation in a desert shrub and observing the decoupling between the active root system (with nodules fixing N gas) deep in the moist soil over the phreatic zone and the seasonally dormant surface root system in the top soil layers linked to the desert atmosphere. I was very much interested in herbivory of both the high moisture content leaves and nutritious seeds due to the uplift of water and nitrogen. I got my second postdoc in New Mexico, a similar thing, on plants flowering due to spring rains. My research on plant-animal interactions evolved into realizing that climate really drives everything, so I should pay attention to that.

I applied for a position as a contractor for the EPA here in Corvallis [Oregon] and was offered the job. I was supposed to look at UV-B radiation impacts on various plants and ecosystems in the US, but because the Montreal Protocol was being signed [which reduced the threat to the UV radiation-blocking ozone layer], the EPA decided to switch the focus of the research from UV-B to climate change. Because I had been working on grasslands in Colorado, they thought I would have the tools necessary to simulate rice growth. So suddenly, I was with a team looking at climate change impacts on rice paddies in Asia. So that was my first climate change-focused project. It was international, working with a German scientist looking at methane, working with people from the Philippines on CO2 emissions from rice paddies, with different concentrations of CO2 and their impacts on the plant. There was an entomologist from Malaysia looking at insects and how they were affected by changes in CO2, temperature, and UV-B. We finished the modeling for the project and found out that economics (the price of rice) was the main driver of the future of rice growth even with changing climate conditions. I left the project when my modeling activities were not required any more.

At EPA I met a friend of my husband modeling biogeography. He asked me to join his team. Jim Lenihan and Chris Daly were part of the team and we designed the first dynamic global vegetation model that included a prognostic for fire. That’s how it all started. I worked on that model until 2017, when I decided to go back to OSU and start teaching about climate change impacts. That’s my story.

Was that the model that led to your landmark, highly-cited paper from 2010 on emerging climate risks for forests? I believe that was the first global assessment of tree mortality from drought and heat stress.

I had met the lead author, Craig Allen, through a friend and we were talking about tree mortality observations around the world that he had been collecting. He asked me if I could write a paragraph on the capability of models simulating climate-driven mortality. I wrote that piece in the paper that says "Models are trying, but it’s really difficult to figure out what exactly causes tree mortality.” Since then, the models have improved. This was a wakeup call to everyone saying, we’re seeing mortality and we need to understand what’s going on and how much worse it’s going to get in the future.

I really wanted to put that in visual format and put it on the web. At the time, I was working for the Conservation Biology Institute (CBI), and I asked if we could get some of the data and map and plot them. (Here’s the map). There was a postdoc from Germany who picked that up and moved it on to add more and more data, so it went on from there. But we were the first to ask for the map; Craig had everything in a spreadsheet. It was a fun project. Well, fun in a way; it was about dead trees.

Can you tell me more about your 2020 paper on global ecosystems and fire? I believe you found that fire globally reduced tree cover area and carbon storage by 10% from 2001-2012?

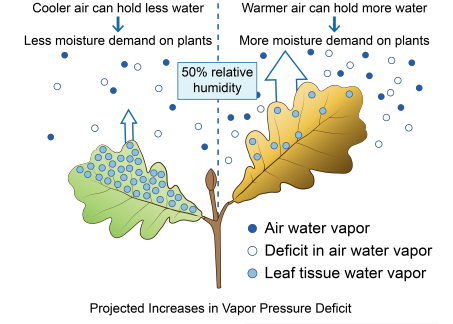

Everybody’s always been using temperature and precipitation. And from the very beginning, we were thinking that dry air was what was really drying up the fuels. We wanted to get VPD, Vapor Pressure Deficit [“the difference between how much moisture is in the air and the amount of moisture in the air at saturation”], from the climate model projections. If you look at the early climate projections, they didn’t provide that. So we kept asking the climate modelers, please make that [VPD data] available as well as the basic climate variables! We ended up being pretty much a spine in their side, but bit by bit, a lot of the teams realized that we really need VPD.

By adding that, we could actually simulate the probable mortality of trees due to dry air. The thing is, temperature actually dries the dead fuel, but the live fuel which is wet dries out very quickly when the air is dry. That’s what’s been happening in the Western US. In dry air, the plant, even if it has its roots in the moist soil, cannot pump water fast enough to actually keep the moisture in the leaves. And so when it’s really dry, and you get wind that moves that dry air through, it actually dries the wet fuel. And then the fire risk increases tremendously. all you need is an ignition and everything will burn. Even though your tree still has roots in water. It’s really an interesting process. It took several years to really figure it out, we were the only ones originally to have VPD in our fire model. That really helped to simulate what was happening.

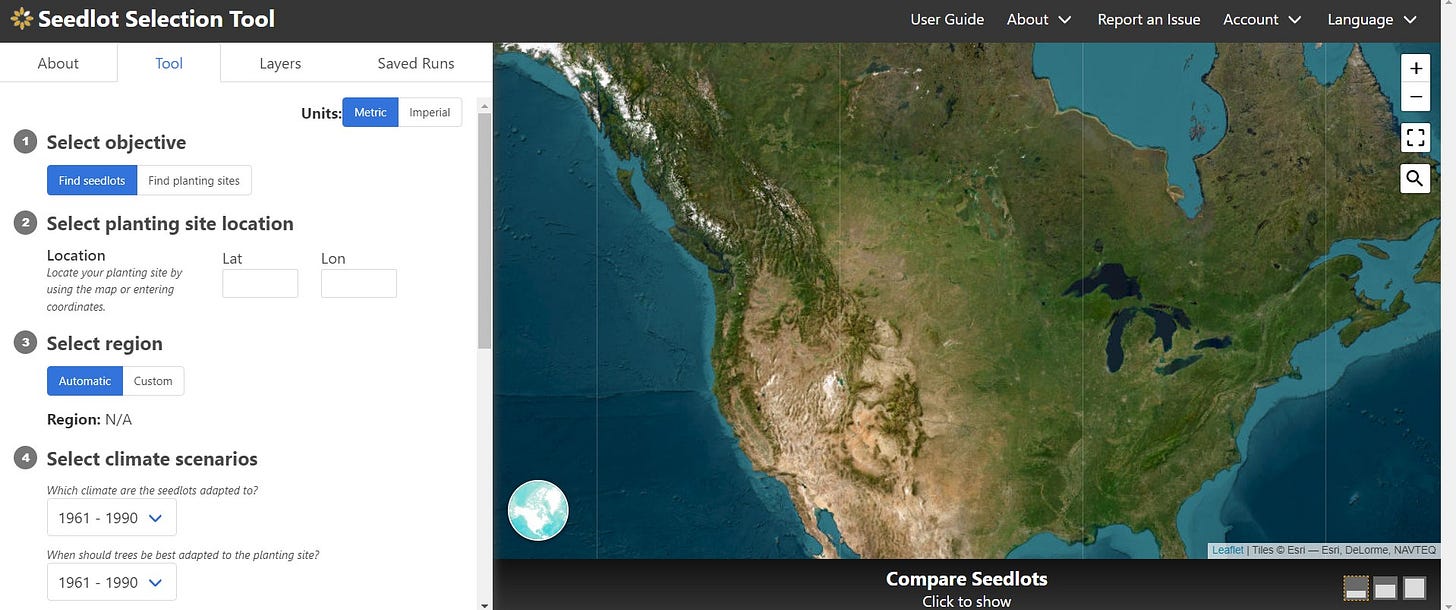

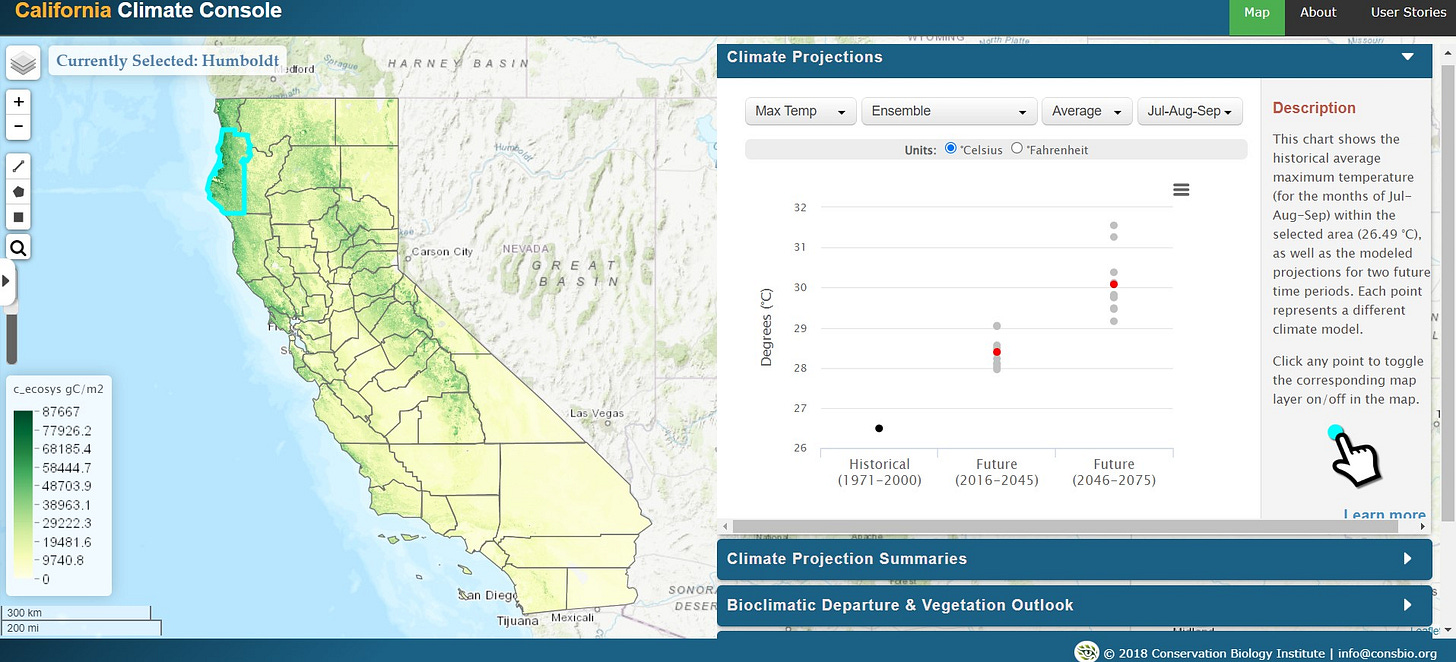

Can you discuss in detail your fascinating mapping work, such as the landmark California Climate Console and the brilliant seedlot selection tool (here’s a paper on it), showing forest managers where to find seeds that are adapted to the likely future climate of their sites? That’s astonishingly powerful for reforestation and rewilding. I am personally very inspired by this as an early-career GIS analyst!

The seedlot selection tool was really cool! A friend of mine was telling me how he was working with people at OSU who were putting together a website on this, but there were problems, and I suggested that he could work with our programmers at the Conservation Biology Institute. So we started working with him and his colleague here at OSU, we started talking about how to put it together. The young programmers were really good and really creative, they were not tree scientists in any way, shape, or form, so they were very curious, sucking the science out of us to really design the website. It was a constant discussion, very successful. The seedlot source tool worked really well. It’s not really finished, they’re doing the sagebrush version right now. Money is always a constraint. CBI is a small NGO and they need to pay everybody’s salary, so it’s expensive. It was a fun project. In my experience, it’s really nice working with programmers and GIS technicians who don’t have much of a science background but enough curiosity that they ask the right questions. They did a really nice job of website and mapping, what we wanted them to show. It’s all about science communication. A very useful exercise for us, scientists, who have not been taught how to communicate effectively with the public.

Fascinating. So, with the California Climate Console, for example, what GIS platform did you use? Something preexisting like ArcGIS, or did you program it from scratch?

It’s in Data Basin, simpler than ArcGIS, which was actually designed by CBI. It’s kind of the baby of the head of the company. It’s inspired by ArcGIS, but free to everybody. That’s how it started, via Data Basin. But the GIS people I worked with were very current with ArcGIS.

Can you discuss your work predicting climate change effects in the Western US? What does the climactic future of the Western US look like?

So I had a Ph.D. student who started as a technician at CBI, and he asked me if he could do a Ph.D. with what we were working on, simulating what was going to happen in the Pacific Northwest. One thing I’ve always been interested in is looking at the climate gradient from southern California all the way to Canada and Alaska. We have a gradient of temperature, obviously, and we see that right now the Arctic is melting, and we’re losing our ice up there, so it’s changing dramatically. In the south, the drier places are going to get drier and the wetter places are going to get wetter. And here, in Oregon in particular, we are in between two places that are changing, but in between we’re in this zone where the predictions are actually pretty difficult.

We know from looking at patterns as we understand them, we should have plenty of water in the fall, and our summers are going to be longer and drier and certainly hotter. We’ll have extreme rain events, we’ll have extreme droughts. The cold snaps might have more of an effect, because everything is going to be used to it being warmer. If you have a warmer winter, and then in the spring you have a harsh frost, which is something that could have happened 30 years ago without much of a problem, everything has gotten used to a warm winter, the plants are almost blooming, and then you get a harsh frost and it kills everything. Very important for agriculture, because you have a lot of loss due to late frosts.

The water, we don’t have usually much water during the summer, because we’re already in a Mediterranean climate, but it’s going to be even worse. And if we lose our snowpack because winters are warmer, that water that used to be stored as snow in the mountains will decrease. We’re going to have to do something to keep the water in the land, not in the stream going to the ocean, so we can have enough water to irrigate in the summer. This is why in the Valley now they’re doing a lot of experiments with dry farming, because irrigation will become a problem. We [in Oregon] are in a zone that will actually have some of the least dramatic changes in the US. We have coastlines that are going to be affected by sea level rise, but to a much lesser extent than, say, Florida. We will have water in the fall, if we’re intelligent enough and know what to do we’ll pay attention to that and might be able to store enough water for the harsh summer heatwaves.

We’re not used to heatwaves; I keep telling people, think about Southern California, think about the heat, think about how it could happen here, think about how people are living there and how we’re living here today. We’re going to have to change our ways. The [California] Central Valley is already very much taxed by the changes in weather, it’s getting hotter and drier and people are having a lot of problems growing what they’ve always grown before. In the [Oregon] Willamette Valley, a lot of people have been planting hazelnuts, at some point, the Valley will have to produce the same things that Central Valley is producing for us now. We’ll have to change and actually produce food for people.

So I think lots of things are going to be changing, but the plants and the animals are going to adapt. We’re going to lose some, but we’re already losing some-we use pesticides, we pollute the air and the water, so we kill things. Climate change is just the cherry on the cake, it’s going to exacerbate everything. Our ways have not been very good for ecosystems. What we need to do is actually have a much lighter touch on the land in order to let animals and plants continue to adapt to the new conditions, and so that we can be prepared for what’s going to be served to us in the next few years.

“What we need to do is actually have a much lighter touch on the land in order to let animals and plants continue to adapt to the new conditions.”

-Dr. Dominique Bachelet

What are your reflections on how policymakers have long ignored climate science (e.g. your title "We told you so 20+ years ago!")? What’s it been like being a climate scientist during the dark days of the Reagan and Bush and Trump Administrations?

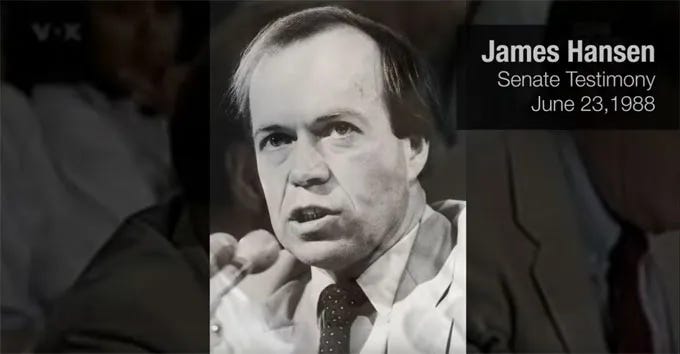

It makes you pull your hair out! Just think of Hansen, in 1988 he was in the Congress of the United States saying “I’m 99% sure we are creating this [global warming] and we should be prepared for this.” If there’s one person should be frustrated, it’s Hansen. He was in front of Congress. We wrote papers, we participated in the IPCC, and then there was this whole political thing. We always have scientific debate, it’s a healthy way for scientists to disagree with each other so science can improve. It’s cherished by scientists. It was taken by the media and politicians to say, “Scientists don’t agree, so we don’t need to do anything about it.”

We’re getting into political issues, and as a scientist and a professor I shouldn’t say anything too untoward. But it’s obvious that the oil lobbies had a lot to do with it, there are papers out now showing that Exxon was paying people to say the wrong thing. And we know now that they had scientists who knew what they were doing, told them what was happening, and then since it did not make sense economically, the company did not change its ways.

And so as a scientist, it’s been more than frustrating. That’s why in 2017 I decided it was time to go teaching and tell students about it, because I found myself totally unable to change the way politicians were thinking and doing things. The US should have been the leader [on climate action], we had the science, the computers, the best models, and we let it all go. It’s a shame, it’s a crime, that the government in the US did not do something about it earlier. We could have been the world leader.

My next question is about this; what are your thoughts on the climate funding in the Inflation Reduction Act? It probably should have come three decades ago, but at long last we’re really properly investing in the renewables transition.

It depends on where and how the money is spent. We could be putting solar panels over every house and parking lot in sunny states. It’s a good intentioned law, Biden is doing the best he can. But I’m just worried, I’ve seen money being distributed before and end up in the wrong pockets, doing the wrong things.

I think the first thing we need to do is change the culture. Why are we still selling SUVs? The new EV SUVs are larger and heavier, thus requiring more electricity to run (defeating the purpose) and they will be a lot more dangerous to small cars, pedestrians and bicyclists. We need to have more bicycle lanes, teach people that they need to walk instead of drive to school and to the store. We need cities that provide more small shops, so you don’t have to go 20 miles to get food. We need to make sure people understand what it means to be driving a car every day.

And that electricity doesn’t come out of nothing, and solar panels are made of materials that have a footprint. There is nothing that costs nothing to the Earth. Everything we do, every action, every credit card swipe, we are emitting, we are using energy. It’s a culture change we need. Look at plastic packaging, plastic is the best thing for the oil industry to sell right now, we’re moving to electric cars so they need to do something with the oil, and they put plastic on everything. We need to stop buying things wrapped up in plastic. I’m as guilty as the next person on that.

“We need to have more bicycle lanes, teach people that they need to walk instead of drive to school and to the store. We need cities that provide more small shops, so you don’t have to go 20 miles to get food.”

-Dr. Dominique Bachelet

When researching you for this interview, I noticed that you were also a painter. How does your climate research influence your art, and vice versa?

It takes my mind off of reality [laughs]. I love nature, I love to paint. I love to paint birds, they’re beautiful. In my mind, they’re free and they enjoy life. We are attached to a piece of land, or a house, but the bird moves on and travels. It’s wonderful. I love the colors. Art is truly a freedom of thinking for me, I’m just enjoying nature and painting is one way to respect that.

What are the most important climate science facts that more people should know? What are the questions I should have asked that I haven’t asked? What is the most important information on this that you wish that everyone had studied in school?

That’s interesting, because Oregon is putting together a package on climate education for all the schools in Oregon. There’s been deniers in this country, but to me, whenever I talk to deniers, it doesn’t matter if somebody “believes” that climate change is here and caused by us. Note that "believe" is absolutely the wrong term to use given all the data we have been collecting and continue to do so. We know the climate is changing. We know we’re losing ice in the poles and the glaciers. We’re getting into a warmer, drier place. I want people to look around and see, change is part of life. Our society is all about stability and thinking that everything is remaining the same, it’s not.

We need to look around and see what’s happening. Despite what you hear about extinctions and the ends of the world, many plants and animals are adapting, changing their ways. We need to look at this, to be aware of this. We need to look at history, and how people have adapted to changes. I have a student doing interviews in the Valley with century farmers, people who have been several generations on the same farm for a century. Those farms have survived through two world wars, the 1910s fires, the very wet, the very cold, and then the last few years’ extreme events. People can be resilient. The Native Americans used to move to find their resources.

We need to actually change the way we think. Restoration-what’s restoration? What’s conservation? We cannot perfectly conserve something that’s changing. Restore to what? What is it we want to restore to? The climate has changed, society has changed, we have roads and parking lots everywhere. We need to change our ways and know that change is inevitable. We know from the climate models, which are our best tools, that it’s going to get warmer and drier. So how do we adapt as a society? We know there’s going to be a lot of movement of people. I think what people need to focus on is population. We’re going to have migrations of people who can no longer live along the coast. Where are those millions of people going? Climate change will cause conflict, over place, water, energy, and food. Every community should be ready to think about immigration of people from other places, other cultures, joining them and trying to share resources.

“We’re going to have migrations of people who can no longer live along the coast. Where are those millions of people going? Climate change will cause conflict, over place, water, energy, and food. Every community should be ready to think about immigration of people from other places, other cultures, joining them and trying to share resources.”

-Dr. Dominique Bachelet

We need to stop having these conflicts, emphasize diplomacy, emphasize learning other languages. This planet will survive. But we [humans], we fight each other so much. We need to change the way we teach our kids in school. We as a society need to change our values and address these issues. In schools, we really need to teach kids to be inclusive and to be ready for change.

Thank you so much!

Another really great interview, Sam! Maybe the best yet, in fact.