Interview: Dr. Christine Wilkinson, Carnivore Ecologist

A fascinating conversation with a carnivore ecologist ranging from Kenya to California

Dr. Christine Wilkinson is a conservation biologist, carnivore ecologist, and National Geographic Explorer, currently researching human-carnivore coexistence in the Lake Nakuru area of Kenya and in the urban spaces of California. She posts on TikTok as The Scrappy Naturalist, and her website is Scrappynaturalist.com.

In the interview below, this writer’s questions and comments are in bold, Dr. Wilkinson’ words are in regular text, and extra clarification (links, etc) added after the interview are in bold italics or footnotes.

So first question, how did you become a conservation biologist and carnivore ecologist? Can you tell your personal story?

I grew up in Queens, New York, where there are quite a lot of urban wildlife but not a lot of the exotic species you tend to see on wildlife TV. But I watched all those TV shows, and I wanted to be the David Attenborough of Queens. I would pretend I had this show, in Queens when I was a kid, I would run around looking for squirrels and cicadas and hornets and cockroaches. I loved the New York City subway rats, they’re a resilient, amazing species, even though a lot of people don't like them.

I like rats too!

I never classify anything as a pest. One man's pest is another man's treasure. But maybe fewer for rats. Just a few of us.

I thought I could be a domestic animal vet. But then I found out that I could work with wildlife. I chose to go to Cornell for undergrad, and I was offered an opportunity to go to the Isles of Shoals, off the coast of Maine. Appledore Island, White, Seavey. There’s a research station there run by Cornell and the University of New Hampshire, and there was an NSF funded opportunity for about 10 or so students from systemically underrepresented backgrounds to do field research.

That field research opportunity was really helpful for me because I had never experienced anything like that. I mean, aside from going to the parks in New York and the beach and stuff a lot growing up, I hadn't even been hiking. We could go deep into the history of Black and brown people in outdoor spaces, I’m sure you know all about it.

And then- because of this opportunity- I had a bunch of biology-focused friends when I started at Cornell. So that was really nice. The best part was that the relationship with that NSF funded grant stayed through my second year, so I got to go for a second summer. The woman who applied for that, Dr. Myra Schulman, changed my life. She became my mentor. She applied for more NSF funding for students interested in conducting research, and that funded my ability to do a research project for my senior thesis. I studied herring gull reproductive success on the same islands. Shoals Marine Lab was my life every summer. I also started getting into mammals a bit as well; I did some small projects on squirrels around campus and I was able to study abroad in Kenya and Tanzania in my junior year.

That pivoted my life to what I do now. When I went to Kenya and Tanzania for the first time, within a couple of weeks I had made some friends and acquaintances, and one of them said to me that if a lion kills a person, we may never see any kind of acknowledgement or compensation, but if a person kills a lion, the government will arrive in two days to arrest them. It was a catalyst for really thinking about social-ecological systems. Communities that are dealing with the conservation challenges are the ones that are going to have the most long lasting and effective solutions and the ones who should have the power in those instances. People are the most important part of conversation.

You recently became a National Geographic Explorer and you’re currently working on a fascinating new NGS grant project to quantify hyenas' and vultures' benefits to people. Why do you think hyenas are so unfairly maligned in human culture? (As I wrote in an article on big cats, The Lion King lies!)

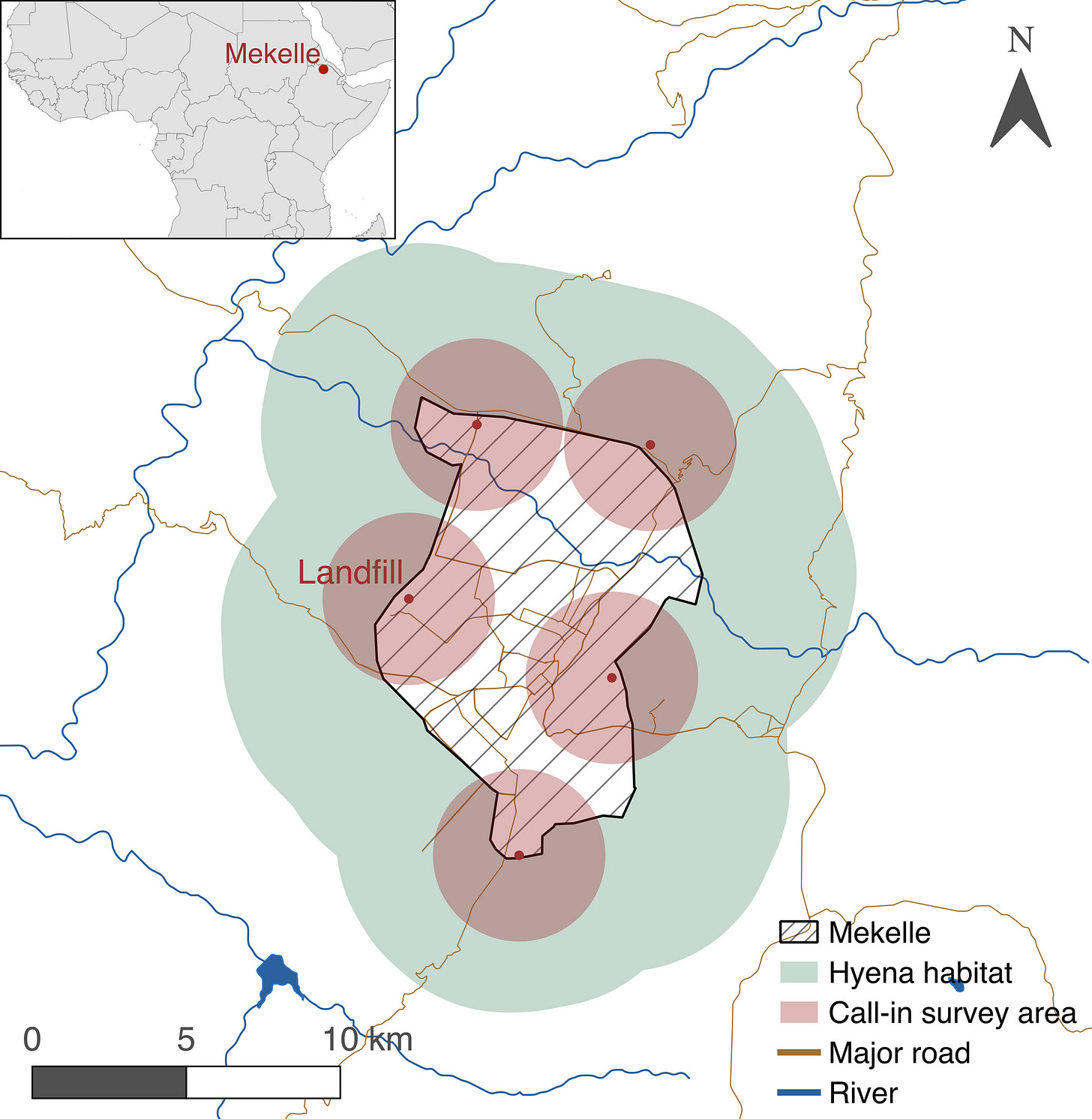

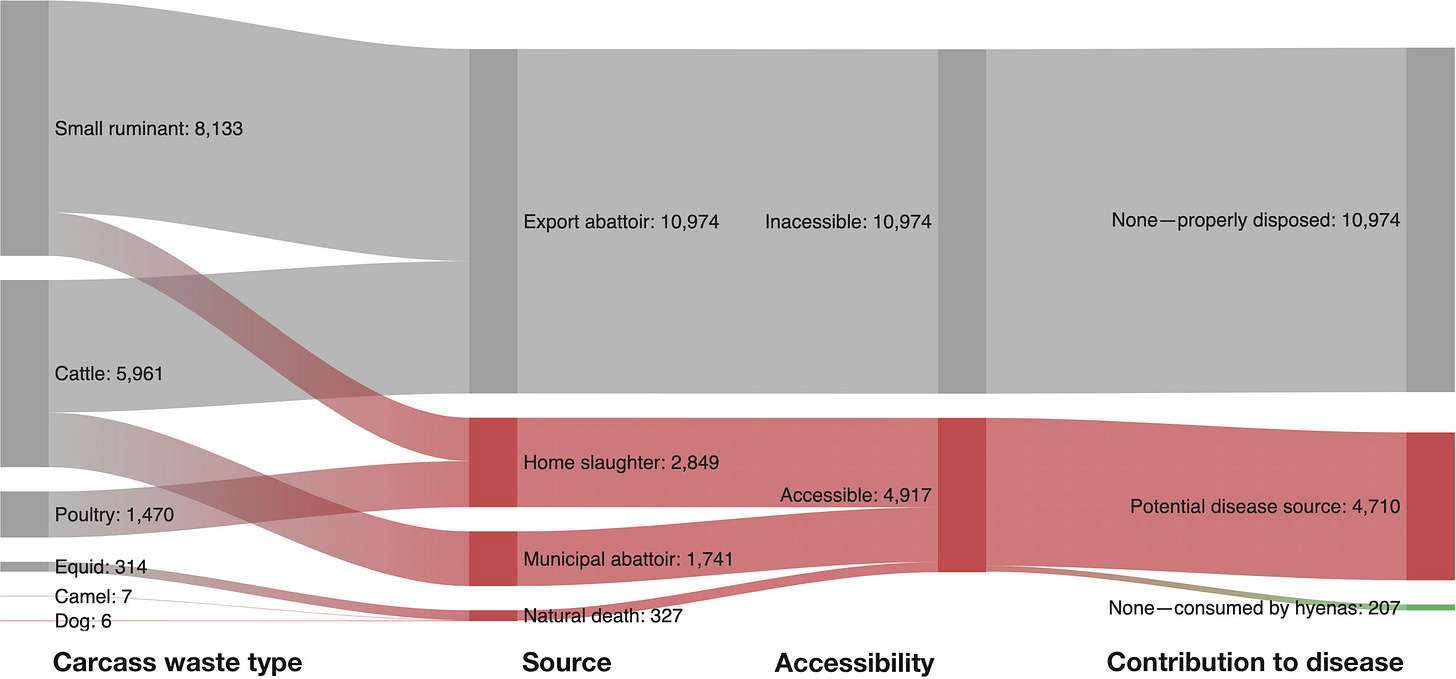

I started this Hyenas in Communities project in 2018-ish. We did a lot of work with community members and with animal behavior and ecology in the area to understand how these animals, hyenas and other carnivores are navigating this super developed landscape, how people are experiencing carnivores on the ground and what the folks want to see happening with conservation in the future. And then that sort of morphed into this second Nat Geo grant about trying to quantify the benefits to people from scavenging species like spotted hyenas and scavenging birds. So we're collaborating with the Peregrine Fund and the Kenya Bird of Prey Trust on that project, essentially helping tawny eagles, which are a scavenging raptor species, and also vultures and then spotted hyenas, and look at their fine scale behavioral interactions with one another in relation to carcasses and disease removal from the landscape.

That project was sparked for a few reasons, partially because, as I'll get into, the spotted hyena and also a lot of scavenging birds are vilified and maligned across a lot of their ranges. That can lead into persecution of or disregard for these animals through actions like poisoning. These actions, along with habitat degradation, etc., then affect all of these different scavenging species across the landscape which then affects ecology and public health and so on. I've been trying to shift the narrative in my work from thinking about conflict to thinking about benefits—coexistence through the lens of benefits.

Because, for example, someone who has one cow that they're relying on for all of their livelihood, someone who is struggling to put food on the table or to deal with their own health challenges, won't necessarily be able to have the bandwidth to care about spotted hyenas and ecology enough to think ahead about the broader impacts of persecution. If I'm someone who's threatened by the presence of hyenas or other species that might cause some sort of threat to my livestock, my livelihood, I might go out and persecute wildlife without thinking about what's going on downstream or how that affects the ecology or how that then affects me later on. And that's reasonable, right? Like if you're dealing with survival, it's really hard to say, hey, don't kill these animals that could threaten your survival, potentially. Even if it's relatively rare in a particular location, conflicts like predation on livestock can still happen and have very negative impacts for people.

So I was like, OK, a key component here would be to quantify benefits to people from vilified animals. And there was actually a great paper that came out in 2021, led by a master's student named Chinmay Sonawane. He was working with Neil Carter and others in parts of Ethiopia where spotted hyenas are not persecuted. In various parts of Ethiopia, there are actually a bunch of cultural views around hyenas that foster coexistence and make it so that hyenas have even sort of shifted into becoming important for ecotourism. Very different than the rest of the range of these animals.

So, Sonawane did a really cool modeling study where they looked at a couple different places where hyenas were eating the refuse from the refuse piles, and quantified what it would be like without hyenas there, how much disease there might be, and what those economic impacts might be, for the diseases that are threatening livestock and people. And he basically showed that hyenas are helping to reduce disease and the economic impacts of disease. My question is how does that play out in a space where hyenas are not tolerated? How does it also play out in a multi-use spaces that rely on agricultural land and are also rapidly urbanizing—like where I work? So looking at those dynamics in a different type of landscape and also looking at those dynamics in relation to other scavenging species is sort of the ideal goal of this new project.

The other part of this newly funded project is making the Humans and Hyenas Alliance, which is the tentative name of our organization, into a Kenyan-led NGO over time. This will involve organizing a lot of capacity building and training for our future Kenyan leaders of the project.

And then just to answer your other question, why are they maligned? Why are they misunderstood, spotted hyenas? Gosh, a lot of different reasons, right? There are a bunch of cultural reasons, such as in some places they’re associated with witchcraft. Lion King certainly didn’t help by depicting them as villainous, stupid, evil, and dirty. And then, of course, they have some special features that make it so that people might fear them.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

The first feature is they're generalists, meaning they're really good at figuring out what to eat and how to obtain it. So they get into a lot of trouble when their cleverness in this regard brings them into contact with people. That's the case with most misunderstood animals, they're able to survive what we throw at them and make it work anyway, and end up pissing us off.

“That's the case with most misunderstood animals, they're able to survive what we throw at them and make it work anyway, and end up pissing us off.”

For spotted hyenas, in particular, they have very unique genitalia that confuses people, and makes them further associate the animal with evil, fear, witchcraft, that sort of thing. But the truth is that spotted hyenas are really amazing!

They're highly social, very clan structure oriented, and there can be very small to extremely large clans. Most of the time the females are leading the clan. Females are also, on average, larger and generally fiercer than the males, and run the show. There are always exceptions to every rule but usually they're more highly ranked than all the males, because the high-ranked males that are born to those high-ranked females often end up emigrating out of the clan.

And they're super intelligent! There’s been at least one study where hyenas were shown to outperform chimpanzees on problem-solving tests because of how social they are. That study was actually done back when there was a captive clan at UC Berkeley, before my time. Then, of course, the reason for Sonewane's study was their potential for taking diseases out of the environment.

And of course, spotted hyenas are apex predators. They're a scavenging species that can make it work regardless. But they’re apex predators. They kill upward of 60 percent or more of their prey.

More than lions, right? Like, lions are technically more scavengers than hyenas?

Yeah, there’s been at least one study where lions have been shown to be more likely to steal a hyena's kill than the other way around. I don't know if that's been replicated anywhere else. But yeah, they're pretty formidable.

And the special thing about them, as far as why we have all these hypotheses about them being cleaners for the environment, is that they have these really, really strong bite forces, and then their stomachs are able to digest bone. So a lot of the time their scat is pure white. Easy to see on the savanna. Very efficient.

About your project in the Lake Nakuru region, can you tell me about the hyenas and the people and landscape and culture? What's the dynamic on the ground?

Where I work, as I mentioned, it's been urbanizing, so that's been kind of interesting to see. I work in several protected areas, but one of them is Lake Nakuru National Park. It's one of only two fully fenced national parks in Kenya. I would say there are ecological and social winners and losers for every fence. But it's especially apparent why maybe that fence could be useful, depending on how it's constructed, because of how much development is happening around outside of the park. Lots of immigration to the region. Nakuru was just gazetted officially as a city a couple of years ago and is one of the fastest growing cities in East Africa. And that's right adjacent to the northern part of the park, against the park. And there is a lot more: folks moving into the area, a lot of power line proliferation, and a lot of other development including major roads. It’s been really interesting to watch. Because of course there are elements of it that are great. As far as development, for example, it’s helpful for people to get better access to power and connections to other regions.

But then there are elements that are like, you know, when they're doing environmental impact assessments, folks like my colleagues at Kenya Bird of Prey Trust or Peregrine Fund are warning developers about putting up types of certain types of power lines, because you're going to knock out scavenging birds. But things are progressing too rapidly.

And so there's this tension between making sure that people have access to what they need and access to being able to move around the landscape. But how do we do that in a way where long-term environmental impacts are assessed holistically? And what does that mean, for example, when we're fencing landscapes without necessarily knowing what the long term impacts could be?

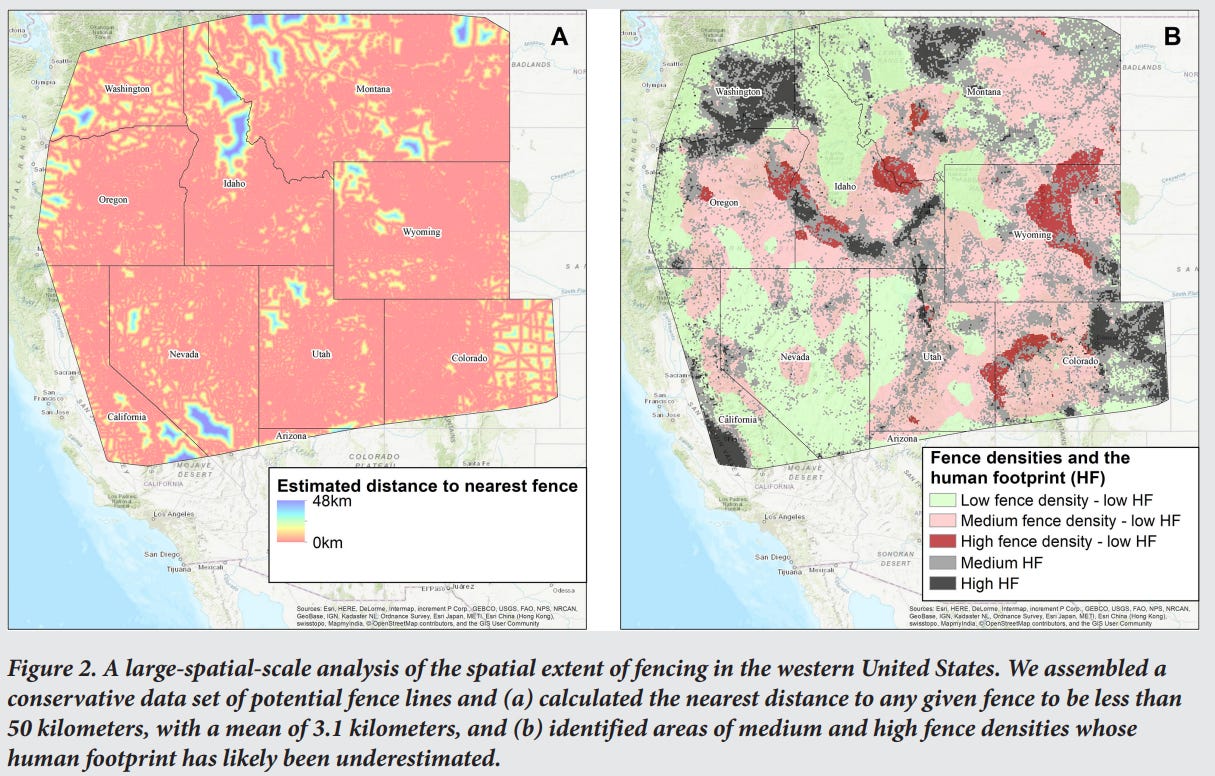

And that’s an issue not just in Kenya, but with fences more generally across the globe. I do a lot of fence ecology work. And a lot of the time, the non-target impacts of fences are not even thought about. Just the initial purpose or the immediate purpose is thought about when you're constructing them. And what's happening 10 to 20 years from now, when there's no maintenance of the fence anymore, and all these other things happen because of the fence’s ecological impacts weren't really analyzed.

That goes for most places, including the U.S., not just Kenya. A lot of time fences aren't even included in environmental impact assessment yet they're crisscrossing our landscapes around this world. There are orders of magnitude more fences than roads on this planet! Yet we're not really thinking about their ecological impacts. I've been watching that happen just as a little microcosm where I work in Kenya, but it's everywhere. I mean, there are different timelines of development where fences are going up or coming down. The Western U.S. is a great example of fences coming down or being converted to wildlife friendly fences because they're not used for the same purposes anymore. But anywhere where people are coming up economically, there's more subdivision, there are more new fences being built, etc.

And so how do we sort of as a global community plan for what that means ecologically and socially for folks who aren't planning those fences or animals that don't have a say, and then make sure ecological processes can continue?

In general, I believe that people should be in the driver's seat of what's happening in their own communities. It’s a push and pull of wondering how do we work with the government, the conservancies, and community members to see how all the different needs can be met while ensuring ecological resilience.

So you're really trying to make sustainable development be more than a buzzword. You’re bringing that ecological voice that wasn't there when they were putting up those fences in the Western U.S. in like the 1880s. Like, you're trying to sort of help Kenya learn from U.S. mistakes in a way, to try to not do as much damage to their wildlife during their industrialization as we did to ours?

Yeah, by assuring communities are in the driver’s seat. A great example of this was when I was giving a presentation last year for the senior warden of the national park and a bunch of city commissioners and community members. And afterward, the warden was like, oh, you've given us all this information about what's been happening with the fence. What do you think we should do about the fence?

And I was like, wow, big question. I'm glad you asked. The answer isn't to take it down, because that could cause all sorts of other impacts to both people and wildlife. The answer is, do things in consultation with one another. Think about how we can build targeted permeability into the fences so that wildlife corridors can be co-created with communities, or so that we can connect the National Park to the conservancy to maybe the other conservancies.

And we need to ask ourselves- what does that take as far as ethical communication and co-creation with community members who might see some of the spillover from making a fence permeable? And which animals is it going to be permeable to? How are people that are living right around the protected areas, who might get some of the extra effects, benefiting from wildlife? Are they able to sell wares to tourists? Are they able to engage in ecotourism? Are they even able to get into the park? A lot of people don’t have cars to enter the park. How do we make sure that there's an ebb and flow of knowledge creation and idea co-creation that's not just top down? So I see that—a connector of science, story, and community—as my role rather than telling people what to do. It's more like working with people on the ground to figure out the science and then facilitating conversations where science can be inserted into those conversations. But taking more of a backseat role, personally.

Spectacular. That's a beautiful rallying cry, really. That's a really powerful lens with which to do conservation work. Thank you for sharing that.

My next question was actually about your fence ecology paper, and you covered quite a lot of that. Anything more you want to share about fence ecology and some of the stuff you found?

I've had lots of folks in the media trying to get me to say, oh, so fences are bad, right? And the answer is no. Fences have social and ecological winners and losers. And the key is figuring out what your target goal is for the fence.

What would an ecological winner from a fence be? What animals benefit from a fence and in what circumstances?

Oh, a great example would be that wild dogs in some of the fenced game reserves in South Africa have been using the fences to more easily hunt prey by pinning prey up against the fence lines. There are also micro-habitats at the fence line that can foster different insect communities and insect biodiversity because of the way that vegetation can grow around the fence. But there are many fence ecology phenomena that a lot of people have studied by accident or as scientific bycatch, but we’re often consciously thinking about what's going on.

For instance, the fence where I work—before they renovated it—consisted of parallel wires, and digging animals like warthogs or hyenas can dig under, allowing even lions to go through existing holes. Anything that can go underneath the fence can get in and out of that protected area, but everything else was sort of stuck in there, most of the time. What does that mean for larger ungulate species that are relying on a very small national park space for resources versus the smaller antelopes that can still get in and out? That kind of thing.

Social winners and losers would be like if I'm someone who wants to come in the park and get firewood because I don't have any firewood, and the fence is in my way, what do I do? Or if I live over here in this community and the fence is really robust over in this other community and it's sort of funneling animals through fence holes toward my community, I'm a social loser of that fence in a certain way.

So there are a lot of different complex elements at play, but I think that there need to be environmental impact assessments for fences that consider not just the immediate goal, but also the potential non-target impacts.

This will include thinking about what the goal is 10 years from now and how we are funding its maintenance over time. Because the ecological winners and losers and the social winners and losers will change over time depending on the maintenance and ecology of that fence, the development nearby, and other factors.

Thank you so much. So another paper I really wanted to ask you about was your paper on public interest in individual wild animals, like how P-22 maybe helped inspire the Wallis Annenberg wildlife crossing project. So I kind of try to do that in my newsletter, when there's research-level stories about individual wild animals, I try to share them because it spikes public interest. There's that old quote, “one death is a tragedy, a million is a statistic,” that very much applies to endangered species. So, can you tell me about how you came to those conclusions about individual animals?

Yeah, so I was really inspired by P-22, especially since I live in California. Essentially when you're looking at animals that are involved in conflict, there’s a distinct pattern in what you typically see reported by community members about conflict. For example, I work on coyotes, too—with San Francisco Animal Care and Control—and in our coyote conflict reports that we get from people, if an animal starts to go around and kill people’s cats and dogs and that kind of thing, people are out there with pitchforks. They're saying, “we need to get rid of these animals. We need to hunt them down. We need to remove them from here. They're killing our pets. Be careful.”

But when P-22 was found hunting someone's dog, everyone was like, “oh, poor baby”, because like they had a connection to him. From him being this very highly publicized, storified individual that was all alone in Griffith Park without a mate for years. And because that storyline had been built up and that connection had been built up with nearby communities, people weren't out to get him with pitchforks. They were mourning him and having a massive funeral for him and all of these other things which are typically super unusual for a conflict-involved animal.

And P-22’s narrative as a charismatic, lonely mountain lion living in Los Angeles fed really well into advertising and building up support behind the Wallis Annenberg wildlife crossing, which raised tens of millions of dollars, if not more, to be created as one of the largest wildlife crossings in the world. And without this “poster puma”, the crossing may not have gained that support. Now that corridor is going to have positive trickle down effects, not just for mountain lions, but for many other animals that need to cross that 10-lane highway in Southern California. This means there will be absolutely massive conservation and ecological benefits from creating a narrative around an individual animal.

So, I was really keen on thinking about how narrative helps us to better create conservation outputs and impacts and galvanize support for conservation. That feeling of being connected to that individual animal that you can see a picture of or that you can hear about—such as the animal’s quirks and behaviors—makes people care more, and perhaps want to give more money. That can then have these trickle down effects onto landscape-scale conservation for the places where that species lives. Long story short, there can be cases where anthropomorphism may be eneficial.

My argument for this piece was that scientists and others need to be thinking carefully about whether and how to intentionally harness narrative around individual animals to promote broader conservation efforts. Because I don't think it's always the case that you should do that. A great example that someone gave was—I had a lot of good conversations after this paper came out—someone was like we shouldn't name animals in places like Yellowstone because then people try to find them and hordes of cars will flock around this animal, if the animal is already hanging out near the roads. And that could be really detrimental to that animal or larger groups of that species in the area—if you're naming an animal and “celebritizing” an animal in a place that's already full of tourists. Whereas the narrative around P-22, as a contrast, was very successful, because you can't easily go find a mountain lion in Griffith Park. He was elusive and there weren’t going to be people flocking around him. So I think there are cases where narrative can be helpful and cases where it can be harmful and cases where it's neutral with no net benefit or detriment.

Interview continues below paywall!

You mentioned Yellowstone. Right off the top of my head, people are already actively trying to kill wolves with radio collars when they stray out of Yellowstone for the stupid Western wolf wars political reasons. If it was a named animal, you can really imagine people actively trying to kill a named animal just because it would upset their political opponents or whatever, right? With an elusive animal like the puma it makes much more sense.

Yeah exactly.

So tell me about your coyote research. It’s, like, the century of the coyote! Coyotes have spread to the east. I've read that there's only the Darien Gap preventing them from getting into South America. Coyotes are like hyenas, right, the hyenas of North America? They've spread so well in human dominated landscapes. Can you tell me about your coyote research?

Coyotes are quite resilient. I think in story and in resilience and in vilification, they are largely equivalent to the spotted hyena. Although they technically fill somewhat different niches since spotties are natural apex predators.

But in a lot of places, coyotes can be considered the new apex predators—it's called mesopredator release—since wolves were historically extirpated in many locations.

I work in various capacities with coyotes and people in the Bay Area and in LA, in California. So one project that I'm currently working on is based in San Francisco and we just had a paper come out about it. Essentially, I’ve been working with San Francisco Animal Care and Control (SFACC), who have been maintaining a community contributed coyote sightings database since 2006. 2012 is when things really took off in earnest. People can call, email, or submit an online form about their coyote sightings around San Francisco and interactions that they've had with coyotes.

My whole goal in my life and career is essentially trying to do work that will be applied, purposeful and useful to folks working on the ground. SFACC is the first responder for many urban wildlife issues in the city. And I knew they had this database, so I reached out. I was connected with Deb Campbell at SFACC by my friend, Tali Caspi, who is also an author on our recent paper and does a lot of amazing work on coyote diets in the city by analyzing their scat. Essentially, I was like, “Deb, what can we do with this database? Would it be useful for us to analyze the spatial and temporal trends of the database and then use it for improving our outreach?” And she thought that would be amazing. SFACC responds to coyote sightings, but they've never really looked at what's going on over time and space and how we can maybe predict what might happen in the future with human-coyote interactions in the city.

Coyotes started to come back to the city in the early 2000s, after having been killed off in the middle of the last century. Now, according to SFACC, Tali Caspi, and some amazing community scientists, they're probably nearing around 100 individuals in the city, which is 49 square miles. That's an estimate, but there's an amazing PhD student out of UC Davis—Monica Serrano—working on the genetics of the coyotes to be able to estimate their populations and genetic relationships more accurately.

We came up with a scheme for essentially taking the qualitative comments that people are submitting and figuring out whether it could be considered a conflict instance with coyotes, analyzing whether people expressed a negative or a positive attitude or opinion regarding coyotes, etc., just breaking out these qualitative elements. We looked at which ecological and social covariates are correlated with where reports are and whether those reports constituted conflict. We also looked at whether coyote conflict seems to be increasing or decreasing over the years, and whether there are certain seasons—like dry season or pup rearing season—where there's more or less conflict.

Now we're planning to use the results from that paper to work with SFACC, Parks and Rec, and others to see if our results can inform the revision of educational practices and workshops around coyote coexistence. My dream is to get educational materials around human-coyote coexistence as a foundational component of the curriculum. I think that should happen anywhere that you're living alongside potentially conflict-involved animals. Start from a young age.

Then in LA, I've been working with UCANR, with an excellent researcher named Dr. Niamh Quinn, who is UCANR’s human-wildlife interactions specialist in SoCal. She is an amazing rodent expert who works on rodenticides, including rodenticides’ effects on coyotes. She had collared 20 coyotes in LA County. I've been working with their data to look at social-ecological predictors of their movement in the city. The background behind that: typically when you're building animal movement models, you're using ecological aspects of the landscape. Things like terrain and vegetation greenness and water availability, which we know that animals respond to. But my argument, including with the hyenas, is that we should be including social factors as well, especially for animals that are living within human dominated landscapes. How are animals responding to societal elements on the landscape as seen through their movements?

That's brilliant! I tried to do a mapping project like that when I was in undergrad, I tried to map like some of the social aspects of protected areas and add that to like a GIS cost surface map.

Exactly. So essentially building out these models to see which are the most predictive, including infrastructure, ecological elements, societal elements, pollution, etc. And that work hopefully will be submitted by the end of the winter.

The whole idea that animals are inherently heterosexual is, of course, absurd. As you know, penguins, giraffes, orangutans, there's so many animals that are well-documented to have same-sex sexual interactions. So could you tell me about your excellent Queer is Natural series and the prevalence of homosexuality across animal species?

Okay, so first of all, I started the series as a sort of a clapback to my super homophobic family. Not that they watch my TikTok, but I needed somewhere to channel that energy to provide people with indisputable scientific elements of queerness in nature. And when I say queerness, I'm using that as an all-encompassing term for things like same-sex sexual behavior, same-sex mating, gender bending, sex changes, hermaphrodism, intersex, etc., within the animal kingdom. When I actually speak about the animals, I purposely describe the behavior (rather than anthropomorphizing) because I wanted to make it impossible for someone to be like, that's not true, or tell me I’m politicizing. I didn't want to provide any avenues for that.

And even though it was a clapback to homophobia against people, we should not have to use queerness in the animal kingdom to justify our need for basic human rights. So even though that's been my sort of way of channeling my energy around this via Queer is Natural, I don't think that it should be necessary or that it should be used to justify people's deservingness of safety and wellbeing.

My travels through this realm have been very exciting. Very soon after I did the first iteration of that series, I came across a fantastic book from the 90s called Biological Exuberance. Highly recommend it. The author, Bruce Bagemihl, compiled records of over a thousand species that have that have shown same sex sexual behaviors or some iteration of queerness. And he did this by reading some scientific literature, but also by reaching out to scientists who study these animals and asking what they've seen [and hadn’t published]. It's currently our only real textbook on the subject, but now we're seeing a lot of stuff burgeoning around the topic. For instance, I was part of a documentary that recently came out in several countries called Queer Planet, about queerness in nature. And then there's an author named Elliot Schrafer, who published a book called Queer Ducks.

It's kind of cool because after I started Queer is Natural, I started to see all this momentum coming up around it. And I've had people thanking me for giving them like a jumping off point to talk to their family or their workplace or their acquaintances, and using it as a more neutral starting place. But I think that there's still a lot to be done in that arena. There are a few recent peer review papers talking about the evolution or taxonomy of same-sex sexual behavior in animals. But that sort of work has been sort of squashed in the past, or hidden. The scientists have been encouraged not to document these behaviors or ways of being. I think that's changing. And hopefully we'll have much more robust information on our thousands (or more) of species that exhibit same-sex sexual behaviors or queerness of some kind.

It is really omnipresent, isn't it?

Yeah. And it's interesting because there have been instances where the conservative news or other conservative entities try to just bury it as well in the present. For instance, that children’s book about the two male penguins in the Central Park Zoo raising an egg together, And Tango Makes Three, was banned in some places. And that was only a few years ago. And there are many other instances of that. So that battle is not over.

I genuinely think that this is the kind of thing which changes people's minds. It shouldn't need to, obviously, like you said, even if humans were the only species that ever did any same-sex sexual behavior, human dignity is more than enough of a reason to grant that freedom. But well before I even heard of your series, I told people same-sex animal factoids like this because it really surprises people and it really made them rethink and made them go, oh, OK, this isn't a fad. This is just like an aspect of existence. It really changed people's perspective. So do you have any, like, favorite sort of stories from your series or examples or animals that you want to show?

A personal favorite of mine is the New Mexico whiptail lizard, which consists entirely of females. They don't need a man! But the cool thing about them is that they still mate with each other sometimes, as in, they go through a copulatory process. And then the female that's on the bottom in that process, like the “traditional female” position you might expect in a lizard, ends up having larger eggs than she would otherwise, according to at least one study. So there can be these benefits of continuing on with the same-sex sexual behavior, despite not even needing to mate, that I find really fascinating. And there are of course tons of other species that go through parthenogenesis.

There are other species, on that note, that have both types of genitalia, male and female, whereby they can lay eggs or they can give sperm—or both—or they can also undergo parthenogenesis. Like in some worms and snails. I mean, wait till we get into plants! Like, gosh, have people ever heard of plant sex? Like that's just a whole amazing business. And then there are the social mammals that end up in orgy situations. Like flying foxes in Australia. Or bonobos, which are a great example since they lots of sex for just maintaining that community bond and resolving conflicts.

As far as sex changes go, love the clownfish as an example of that. So they basically queue up—there’s one female and a bunch of males. And then once the female dies, the next biggest male becomes the new breeding female, and so on. So just like very, very cool queuing process that's just part of their ecology. And they're not the only ones.

Yeah, like that Finding Nemo joke. I was a biology nerd as a kid, and there was sort of a running sort of joke in my teenage years that if Finding Nemo was accurate, once Nemo's mother died, Marvin would have turned into a female.

Yeah, he would have! It was inaccurate, the film.

So can you tell me about how you use GIS tools and participatory community mapping and stuff like that? Like do you use ArcGIS, QGIS? Can you tell me more about how you do mapping?

Yeah, for sure. I use GIS in a lot of what I do.

I'm often navigating in ArcGIS Pro, although I just saw that they just released an R package that seamlessly integrates—well, “seamlessly,” we'll see how it goes—ArcGIS into R, which is great because I am sometimes using R for my spatial analysis, especially with my movement analyses. I use a ton of R

We know we like our Esri products for making pretty maps. And now it's a bit more intuitive and less glitchy than it used to be in the past. But I do recommend QGIS as a free option. When I've run workshops in Kenya, I run them in Arc and Q, just so that people have QGIS as well.

I get my toe into Google Earth Engine in my Masters and I loved it but I haven't had an opportunity to use it much more since. It keeps being on my to-do list of stuff to play with when I have more time. But it's really good, it's really cool. I highly recommend

I do use Google Earth Engine sometimes, not as much as I should. It’s just epic! They have so many really fine scale data sets for you to be able to use. So definitely recommend that.

And then as far as participatory mapping, when I was working on the big participatory mapping project, it was in places where we didn't have much electricity or access to signal or anything. So we actually used Field Papers, which is a paper mapping service. Through Field Papers, you can get a get a map of your field site with whatever base map that you want. I use something very simple. And then you print out the map and it comes out with a QR code in the bottom right and some reference points around the outside so that when people draw on the map later, you can take a picture of it from directly above, feed it back into Field Papers, and it is automatically georeferenced.

So then what you're left with is the second half of the digitization process, which is getting an army of undergrads or other folks to help you do all the tracing and create shapefiles. But at least you don't have to georeference anything anymore. So that's a nice tool for if you're working in a place where electricity or other resources are scarce.

Of course, it's still a ton of work. We had 600 maps to get through, which took a year.

I bet an LLM could probably do some stuff with that now. I've been playing around with some of the new generative AI models. There is the hallucination issue, of course, which means it always needs human checking, but some of them are actually really impressive. I'm going to transcribe this interview with an AI and it's really, really useful. It can take away a lot of the grunt work like that.

That's the hope. It probably depends also on what you're trying to do, right? On my participatory maps, we had 12 different people drawing with different pen colors that were anonymously associated with their interview answers. And then they had three or four questions that they were answering on each map with different symbologies, such as points, lines, etc.

It also depends on how much data you're willing to lose. Maybe for certain projects you can afford to lose data. Another example of AI that is used a lot in my field is for camera trapping. People are using AI for animal identification, which is really useful. But, for example, when I was doing my fence ecology work, I couldn't afford the 5 to 10% error rate—at the time—of missing an animal that was going under a fence. I did many of those classifications manually because I needed to log every single animal that passed under the fence. Whereas if you're doing a camera grid across the landscape to determine occupancy, for example, you may actually be able to afford the error. So yeah, it just depends. But as far as participatory mapping, there are tons of digital tools out there!

Fascinating. I don't want to overstep on your time, it's been one hour.

That’s all right.

Thank you.

Thank you. Bye!

Have a lovely day.

You too!