The Weekly Anthropocene Interviews: Mary Yap, CEO of Lithos Carbon

A Scientist Spotlight Interview

Mary Yap is the co-founder and CEO of Lithos Carbon, a pioneering enhanced rock weathering company working to fight climate change by spreading carbon-sequestering, mineral-rich basalt dust on farmers’ fields.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Ms. Yap’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview. Otherwise unlabeled photos are from this Lithos Carbon post.

Can you tell me more about your personal story and journey towards Lithos Carbon? For example, I'd love to hear more about your research at Yale and your family's farming roots in Taiwan! What brought you to this place?

So let’s see, where’s the best place to start? First, I love your newsletter, thanks so much for reaching out. It was exciting to dig through some of the profiles you’re writing on different ways of tackling the climate crisis. I think that’s the most important problem of our generation, and I am so excited to see the kinds of different interdisciplinary thinkers that you’re bringing together. So kudos to you for that. That’s awesome, and I love that you’re doing this in your free time and democratizing climate science so we can all get involved. I just wanted to say that.

Secondly, my journey to climate has been a little bit winding. I have always loved nature, I was a nature junkie growing up. I grew up in Seattle, Washington, I went hiking all the time, my family took road trips to the redwoods in California. And my entire family in Taiwan are actually farmers, so not too long ago my family were all farmers, with only my mom, my sister, and I over here in the States. So I’ve always had a very deep appreciation for the complexity of evolution and of life. The fact that there is life on this planet is mind-blowing, the fact that we have cultivated so much of it is mind-blowing. And the risk of us causing a mass extinction is terrifying. I’ve had such an appreciation for the beauty and the complexity and the wonder that life exists, and that the fact that it’s so fragile is terrifying. I spent a little time scuba-diving and visiting the Galapagos, and you see this up close. Over millions of years of evolution, incredible endemic species have involved in such unique, special ways in the Galapagos. And yet at the same time it’s so easy to destroy that. The ecosystems we’re living in now are very fragile, even while life itself is resilient.

So the question for me is, how do we address this? How do we tackle the climate crisis that is upon us? I actually had a very different journey that a lot of folks who are deep in the climate space. I started with consumer software. When I was 18, I had spent two years at the University of Chicago, studying plant biology there. But I realized I wanted to build something that had impact and scale, and I didn’t want to just wait to do that. So I actually dropped out of school, even though I had a full scholarship. My mom was so mad! Hot take for folks that are in school: I don’t know that you necessarily need to have a higher degree to tackle the problems that are important. I think the most important thing, whether you’re in school or out of school, is to figure out what problem really excites you and brings you alive, then fit your skills or develop the skills you need to tackle that.

“Hot take for folks that are in school: I don’t know that you necessarily need to have a higher degree to tackle the problems that are important. I think the most important thing, whether you’re in school or out of school, is to figure out what problem really excites you and brings you alive, then fit your skills or develop the skills you need to tackle that.”

-Mary Yap

So for what it’s worth, I dropped out of school, taught myself to code, taught myself to design, and spent the first six years of my career launching early-stage consumer software companies. It was really exciting to me to build brand new things from scratch, to figure out how to solve a problem for real users, to get the first user, the thousandth user, the millionth user. So for six years, that’s what I did. Not climate. Then six years in, I had a realization. I lost a couple close friends in 2016, who passed away from accidents. When you’re 24, and a tragedy of that scale happens, it makes you take a very hard look at your life and what you are spending your time on, because you realize our time here as individuals is limited. And our survival, as individuals or as a greater society, is not guaranteed. So at that moment, I realized that consumer software was fun, but I wanted to make an impact in a different realm. So I actually pivoted there, I took a little bit of time off. I spent time in Southeast Asia with farmers, including my family. I spent some time in the Galapagos, scuba diving, because I’m a big marine nerd. And I decided that I would devote the rest of my life, however long or short that might be, to climate. So I went to Yale. I studied earth and planetary sciences and geology as well as urbanism there. I did a bunch of research on urbanism, how do you upcycle, how do you develop sophisticated, intelligent cities for the future. I got a little bit disillusioned there because I found that there was too much greenwashing in the urban field, just because of the way that the economic incentives are set up. I realized I didn’t necessarily want to be part of the flywheel of speculative development. There are incredible architects and urban planners out there, but I wanted to do something different that made a data-driven impact on the climate crisis.

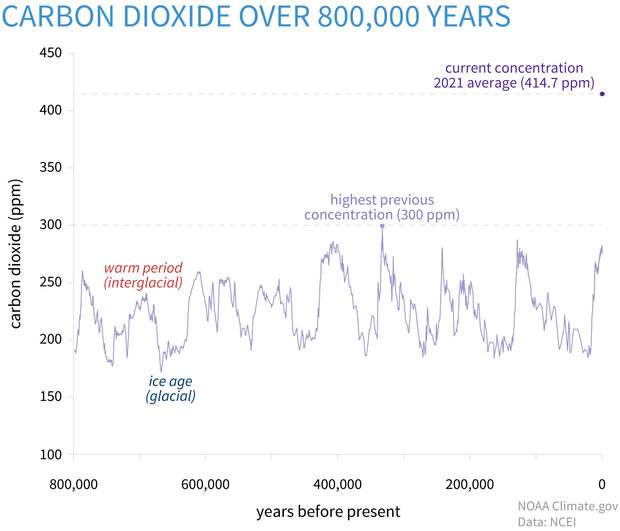

So that brings us to CDR, carbon dioxide removal. That was really exciting to me. I was like wow, this is so important, we absolutely need to figure out how to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. But it also felt like an insurmountable goal. As you probably know, it is so hard, so energy-intensive, so expensive, and so challenging to figure out how to remove that CO2 from a diluted stream. It’s 0.04% CO2 in the atmosphere. (To be precise, Earth’s atmosphere was about 414 parts per million (0.0414%) CO2 in 2021, up sharply from under 320 in 1960 and under 280 in the 1700s before the Industrial Revolution. The highest concentration in the 800,000 years before that, longer than the entire lifespan of our species, was 300 ppm).

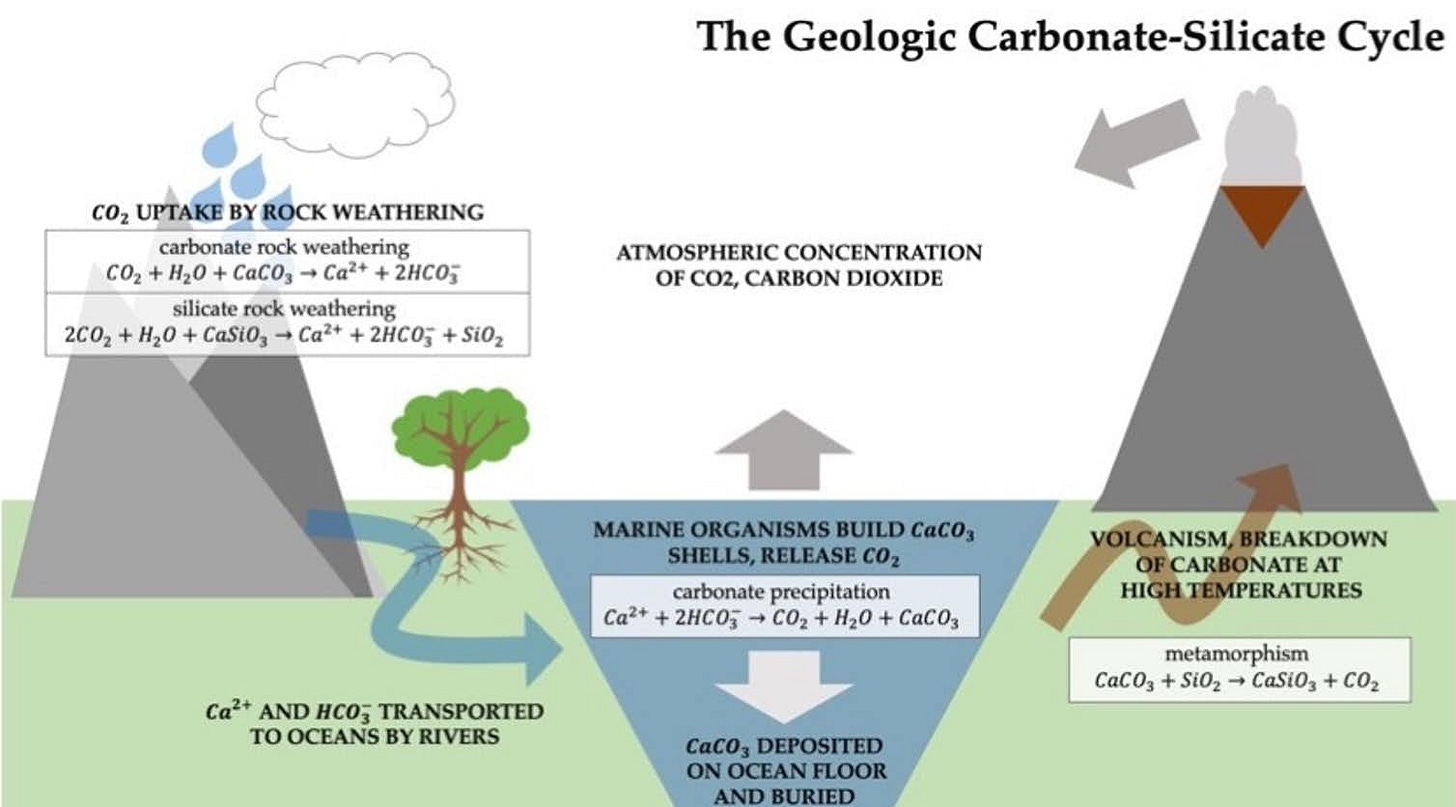

So I dug into a variety of methods. I looked at direct air capture, I looked at nature based solutions. And one of the things that is most exciting to us at Lithos Carbon is that we are able here with enhanced rock weathering to pair something that can scale to a consumer perspective, with real benefits to real farmers on the ground, with some thing that permanently removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. That is so unique We don’t need a factory floor to build direct air capture machines. And I love direct air capture, don’t get me wrong. I do not see them as competitors, I’m a massive fan of all the founders in the space. The planet needs us at work. But we also need multiple methods to work. So what we do at Lithos Carbon is permanent carbon removal through enhanced rock weathering, which is something that Earth has done for four and a half billion years, and we’re scaling this up in a way that actually taps into needs in the market, which I think-hopefully!-is one of the fastest ways of scaling.

So, that was a lot! I’ll pause there.

That was great, thank you so much! That’s all really cool. That’s also a perfect segue into Lithos Carbon. Can you tell me the core pitch for Lithos Carbon? Who are you guys, what are you doing, and why are you a unique solution?

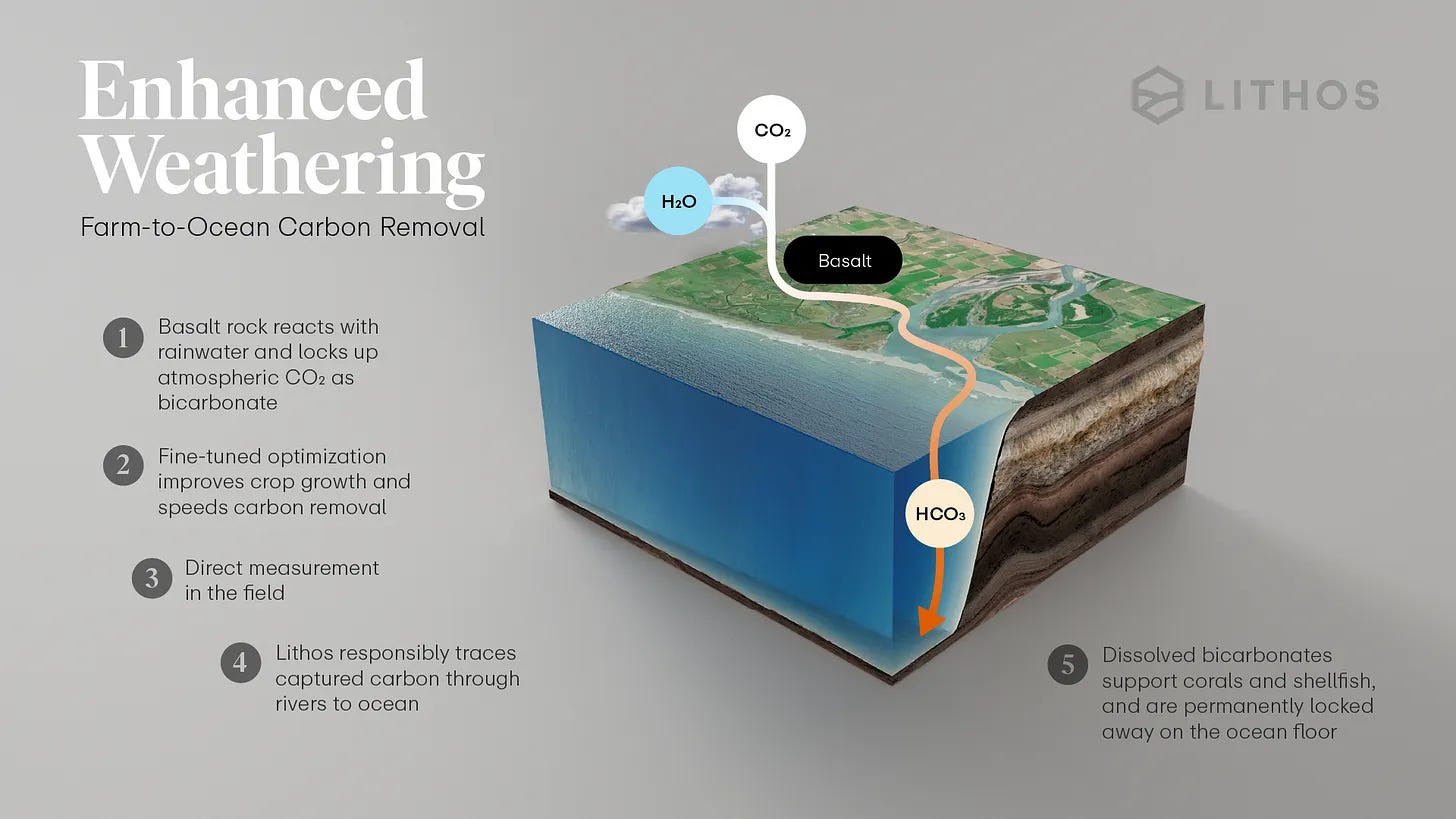

At Lithos Carbon, our mission is to transform farmland into carbon removal centers. What we’re doing is permanently removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, storing it for ten thousand years or longer, and trying to do that at planetary scale. Our vision here is that you can actually deploy enhanced rock weathering on any arable land worldwide, which means any land that has water flowing over it. You can do this in forests, prairies, grasslands, et cetera. But we’ve chosen specifically to focus on agricultural lands because we see that there’s an inherent need in the market. We believe this is one of the fastest ways of scaling while also helping the bottom lines of agricultural growers around the world. If you think about it, there are two problems that human beings really need to solve. The obvious one that we’re chatting about today is climate crisis. If we don’t solve that, we’re in deep waters, literally. But the second thing is, the population is growing, we need to feed a growing population with the same or less land.

How do we do that? Ideally, we’d need to get even more efficient with the crop inputs we’re using, get even more efficient with agriculture. And the good news is we’ve actually done this before, we’ve had multiple agricultural revolutions where we’ve completely transformed the way that the food that feeds the humans on this planet is grown. And that’s critical. I know ChatGPT exists, but we are not robots yet, we need to eat. The exciting thing about Lithos Carbon is that we tackle both birds with one stone.

So what we do at Lithos Carbon is we take volcanic rock dust, specifically basalt, we upcycle that in a circular economy, and we bring that to farmers. Where it can, one, capture carbon permanently, and two, improve their crop yields and improve their bottom line. And that’s the thing I’m really, really stoked about. I think if you can build something that farmers want and love and trust and need, then you can really tackle the climate crisis at scale. You don’t need to rely on the factory floor. You don’t want to change up all their practices, you want to plug in with something that absolutely makes sense for them. So my family are farmers in Taiwan, and I think something key here to remember that most folks in tech don’t remember is that farmers run small businesses. They’re also entrepreneurs. They’re working on innovating and keeping this land in their family for generations. Along those lines, they can’t take massive risks with their crop yields. And that’s a problem, typically, when you have a new fertilizer on the market. The farmer is like, wait, is this going to damage my crop yield? Is this going to damage my bottom line? At Lithos Carbon, we focus on making that answer a resolute no.

We make it very, very easy for farmers to do this. We actually give them the basalt rock dust for free. Which is a hot take, not everyone is massively supportive of this from a market perspective. But we choose to do that, because we think that is the best way of helping their bottom line and proving confidence in what we are doing. So, one, we give them this basalt rock dust for free, and it actually replaces an expensive existing rock dust, limestone, which is what all farmers use to deacidify their fields. What limestone does, it’s CACO3, is it helps deacidify your fields, and your fields will naturally acidify if you use nitrogen fertilizer. Which is the most common fertilizer, it’s what you have to use if you want to grow crops at the rate that we’re seeing today. However, the limestone actually releases CO2 as it dissolves in your field. It’s CaCO3, so 40% of its weight is from CO2. That’s not great. We’re actually replacing that. It’s a mitigation, we don’t claim the carbon credit on that, it’s just a good thing we’re doing. The second thing is that basalt can also deacidify your field, but not just that, it can actually do other things. It releases all these macronutrients and micronutrients into your field. Phosphorus, potassium, iron, a little bit of zinc, calcium, magnesium, it releases these into the fields. And some of these are things that farmers are actually paying a lot of money for today. For what it’s worth, there are small-scale organic farmers that already use small amounts of basalt rock dust today as a fertilizer for their fields. If you think about the Amazon Rainforest, or those beautiful, green, lush jungles in Hawaii, that’s growing on basalt soil. That soil was just made over millions of years. We’re speeding that up with Lithos.

So we’re providing a rock dust input to farms that helps their bottom line. We’re replacing something expensive, the limestone that they were already using today.

“We’re providing a rock dust input to farms that helps their bottom line. We’re replacing something expensive, the limestone that they were already using today.”

-Mary Yap

And we can also improve the fertilization on their farms, and in some cases improve their crop yields by up to 47%. I will say up front that it’s not normally 47%, it’s very, very variable, depending on the soil conditions, but that’s just extra gravy on top of the entire program for farmers. So in short, we focus very much on putting farmers first, making something that works for them. Making sure that we are being careful and safe with local ecosystems. I think the environmental justice angle needs to be an important part of the conversation early on. We’ve chosen basalt, not a different rock, because of safety. Organic farmers use it, it has passed stringent organic farming regulations, some of the most stringent regulations in America. Basalt is good for your soils. We make sure we don’t have heavy metals like nickel and chromium, those can be bad for the ecosystem, we’re very careful about that. Some of the other rocks considered for enhanced rock weathering have a lot of heavy metals and are outlawed in the EU. That’s why we use basalt; it’s safe, it’s good for the growers. It may not be the most efficient rock for carbon capture, but it’s safe. We think the most important, first principle you should have, is “do no harm.”

And then the second half of what we do at Lithos is being very careful about the carbon that we are removing. Making sure that we are measuring that on a field by field basis. We have a lot of technology to measure the carbon removal carefully. Because, to be up front here, the field is very nascent, and you make what you measure. If you are not measuring things up front, if you’re just throwing rock dust on fields and you don’t know what’s happening, how can you reassure buyers and policymakers and local ecologists and farmers that good things are happening? That this extra work that we’re doing is capturing carbon?

That’s a really good point. Because as you know, there’s been truly staggering amounts of fraud in the carbon credit field recently. I’m sure you saw the study recently that found that California’s carbon market as a whole had a net emitting effect! Here’s an in-depth look at how fraudulent and misleadingly calculated credits added up to make this program worse than nothing. And in Brazil, Bolsonaro tried to screw around with Kyoto Protocol carbon offsets (attempting to double-count them, essentially). Another recent analysis found that 90% of carbon credits certified by Verra, the world’s leading carbon credit standard, were worthless or worse. There’s really been a huge amount of misconduct. I’d love to hear your solution to this. I know there’s been a lot of innovation with Stripe Climate and groups like that.

I completely agree with you, Sam. It’s prescient to point that out. I think that’s absolutely critical for us to discuss, and I think that everyone in the CDR (carbon dioxide removal) space should be discussing this. The key thing to point out here, and you touched upon it briefly, is that we need to go for scale. CDR does not matter if we collectively capture, like, 50,000 tonnes of carbon. That’s like scooping a cup of water out of the ocean. We need to get to billions of tonnes. That takes a little bit of time. And to have time to be actually doing this at scale, we need to build an enduring, credible market. If you do not have an enduring, credible market, it’ll just implode itself over time.

So along those lines, that’s why I think it’s so critical for us to invest up front so you don’t get blowback down the line. And also so that, again, you’re doing good. Although it’s a lot more work than doing things with no measurements, at Lithos Carbon we very much focus on measuring and making a real CDR impact. So as you guys probably know, this is called MRV, monitoring, reporting, and verification. Our take on this is kind of unique because we like to do it on a site-specific basis, and also empirically. So let me get into this.

Please do.

One of the things that’s very interesting that you’ll find in enhanced rock weathering is that the way your technology works is very, very dependent on the site. I often say that enhanced rock weathering is a little bit like baking. The theory is quite simple: throw some rock dust on a field, it should capture some carbon, because there’s more surface area on the rock dust. Cool. But in practice, it’s very complicated. Like, I know flour and water go into bread. Sourdough has never worked for me, because there’s a lot of complex chemistry that goes into making that bread work. Same thing for enhanced rock weathering. So when we go to a field, and we give the same exact basalt rock to two different farmers in the same county, we see completely different carbon removal results. And that’s a key thing to realize. That’s part of the reason that we don’t think a model-based approach will work for the first few years of this nascent market. We do think at scale it will work, but we don’t believe, based on the real data we’re seeing in the field, that that’s possible. We need to understand the different parameters. Even within a field we see totally different carbon capture rates. And that’s because fields are not homogeneous, they are very, very different from each side. The topology, the way you’ve tilled the soil, the different soil types, they all vary. All these different parameters are very important, and actually changing how the carbon removal happens and how quickly it happens. If you look at the literature, it will say something like “Sometimes enhanced rock weathering can take 1000 years, or 100 years, or 50 years, or 10 years.” The value of carbon capture this year is totally different that the value of carbon capture 50 years from now. So, again, we need to have transparency, accountability, and openness in the market. We spend a lot of our time measuring this empirically on a site-by-site basis.

So those are the first principles we work from. What we do specifically is on every single farm where we deploy, we grab soil samples. Soil sampling is a pretty common things, farmers already do that. They do that because they need to know how much fertilizer to apply; buy too much, lose money, buy too little, you also obviously lose money. So they do soil samples to get a good reading on what’s going on in their fields. What we do is we actually also get a little bit of that soil that they’re sampling on their fields, we send that to our laboratories, and we add a special isotope spike to it that allows to understand in a very precise way how the basalt is weathering. How the basalt is changing over time, how it’s being converted to bicarbonate, which is HCO3-, the special permanent form of carbon that we’re converting atmospheric CO2 into, and understand how that is happening in an integrated way over time.

So what we do is, we apply the basalt to the field. We always do control strips, we always have a section of the field that didn’t have basalt, where the farmer applies limestone. Then six months later, seven months later, whenever the harvest is done, we get another soil sample. And that soil sample will tell us how much carbon has been captured, how much basalt has been weathering. And that big uncertainty there for us is how much the basalt has been weathering. Basalt is actually one of the hardest rocks on earth. It’s not like limestone, which is like chalk, it’ll dissolve in your glass of water. Basalt is not going to dissolve in your glass of water. Even though we’re using dust, it’s actually a little bit harder to dissolve that stuff. So we want to check that we’re dissolving that, it’s capturing carbon, et cetera, and that’s what we’re actually measuring on a field-by-field basis on each of our farms. Then we take that measurement of the basalt weathering, that dissolution of the basalt that is capturing carbon, and we’re able to understand how much bicarbonate should have been created from that. We don’t end there! Because that’s just one step of the process, creating the bicarbonate. After that, there’s just also the fact that these bicarbonate ions just flow off into rivers and groundwater, into the open ocean. And there they should help deacidify the ocean, and they can also become the shells of phytoplankton and crabs and things like that, and eventually deposited at the bottom of the ocean where the carbon will be stored for a very, very long time. Obviously we’re not going to go sample the ocean. But we do work on a riverine transport model that allows us to understand how the bicarbonate should be flowing off on a catchment by catchment basis, to the ocean. And also making sure that there’s no leakage, or at least if there is leakage, understanding it. Because in certain kinds of settings, and certain kinds of river chemistries, there is a small chance-and we’re just going to be upfront about this-there is a small chance that some of the bicarbonate ions could leak back out as CO2. And again, we want to be very upfront about that. As a company, it’s harder to be upfront about everything. It would be much easier to say “Oh my gosh, here’s this rock dust on your field, it will definitely capture carbon, everything is straightforward!” But it’s much more complex that that, and we actually want this to work. So we spent time on those parts of the process. We’ve spent a lot of our time measuring the actual CO2 capture on the field, that creation of the bicarbonate through the dissolution of the basalt. Then we do a bunch of stuff on the riverside, from farms to ocean.

That’s awesome. That sounds way, way, way more reputable that a lot of the “pick a number from the scientific literature and pray” methods of verification we’ve been seeing in a lot of other carbon capture projects. And I was also wondering, one of the inherent limits in certain forms of carbon capture has been permanency. If carbon is integrated in soils, that’s a lot more permanence than claiming if you buy a chunk of forest it’ll still be there in a hundred years. Which in the age of insect plagues and wildfires has eroded a lot of carbon credit value recently.

That’s really hard. I think there are certain settings where reforestation makes a lot of sense. There’s a fantastic group in Brazil reforesting the Amazon, and I’m a big fan of them. And that absolutely makes sense.

Certainly, I’m not trying to attack reforestation. It just causes a lot of problems when carbon credits are sold for 100 years’ worth of forest carbon sequestration, and then the forest burns down. Forests should absolutely be preserved for their biological and climate value, but trying to quantify that in advance and sell it as a carbon credit is difficult and can lead to counterproductive outcomes.

But I agree with you, the permanency is what I’m so excited about. And that’s why we’re building Lithos Carbon, we think it’s so critical to permanently draw it down. The beauty of enhanced rock weathering is that this is something that the Earth has been doing for a very long time. It literally already removes about a billion tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere every single year, through natural silicate weathering. (For comparison, the USA emitted about 5.59 billion tonnes of CO2 in 2021). When the Himalayas uplifted, 40 to 50 million years ago, it also caused the temperature to drop by a couple degrees, and actually launched an ice age. That was because there was so much more rock exposed from the Himalayas uplifting! We know that this can work at scale because Earth has done this before, and has been doing this for four and a half billion years.

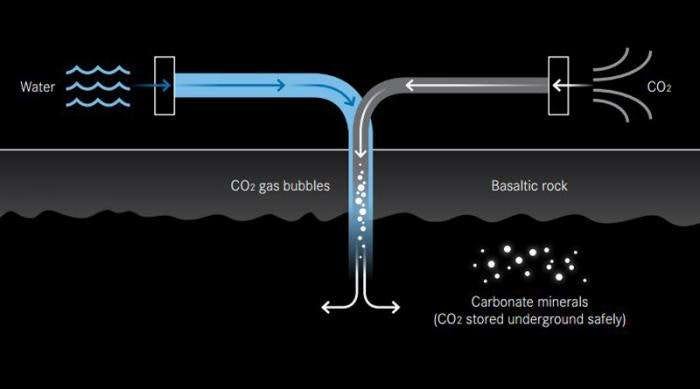

And for what it’s worth, with direct air capture, they’re actually also doing a form of this. A lot of them are injecting that CO2 into water, kind of like a SodaStream, and then inject that bubbly, acidic water into basalt, where it mineralizes and it’s permanently stored.

Are you guys trying to qualify for Section 45Q, the newly expanded carbon sequestration tax credit in the Inflation Reduction Act?

We would love to. We know we don’t qualify yet, because enhanced rock weathering has not been named [as a qualifying technology]. But if you know folks who are working on that, I would love to speak with them. I’ve been trying to figure this out, slowly, in the background. We’re doing permanent carbon removal, we’re measuring it with a lot of work. We would love to figure out how we could qualify for that credit, and also help our farmers more and scale faster.

At least for as long as the Biden Administration is around, I suspect people will be trying to help you. There’s a sense of trying to make things work, which unfortunately is not always there in American government. And you are currently making money selling carbon credits, right?

We already sell carbon credits, and we already pay our farmers as well using those carbon credits. We already cover the basalt for our farmers using the carbon questions.

What marketplaces are you using? And what registries, what certifications?

There’s only one enhanced rock weathering [certification] methodology on the market, and it’s by Puro, we helped write the Puro certifications. Currently we don’t sell in marketplaces yet, but we do think that’s a potentially powerful channel for growth Currently we sell direct to a number of different buyers.

What buyers?

The one that is public is Frontier Climate. We’re part of their first batch of carbon removal purchases. I think we were the largest supplier of tonnes [of sequestered carbon] in their first cycle. Frontier is Google and Facebook-or rather Alphabet and Meta, the new names-and Stripe, Shopify, and McKinsey. They’re very scientifically driven, very rigorous in their reviews, and we’re excited to be part of that cohort. So that’s the one that is live, we haven’t announced the other ones yet. But we are actively capturing carbon and selling that today.

How are things going with the current trial farms for Lithos' basalt treatment (is there a map?), what are the logistics like, and what are your plans to scale up? Can any farm apply to be part of this?

Great question. The thing that we’re excited about here is that we are working on scaling this live. This is not just academic, we are figuring out how this works, doing the research, creating this spiral of innovation and growth through our life deployments. We are already live on over a thousand acres, with many more thousands that are going to go live this year. It’s literally being deployed today.

“We are already live on over a thousand acres, with many more thousands that are going to go live this year. It’s literally being deployed today.”

-Mary Yap

We are live on the Midwest and across the East Coast. And that’s where we focused initially, but we’re now doing it anywhere in America that’s not terribly dry, so no deserts. We’re really excited about the scale-up. We are working with a number of different farmers today, and we actually have a long waitlist. We’re always trying to capture more data about different types of soil and different types of crops. That’s the key thing. We don’t want to just do the same crops and same soil over and over and over again. That’s great, that’s reliable and repeatable, but it doesn’t have learning. Where we are today, Sam, is we are focused on the rate of learning. I think the biggest thing for us is we want as many learnings as quickly as possible, so that can fuel additional technology innovation and additional growth and scale-up in 2024. 2023 is all about learning. We are hoping to capture at least ten thousand metric tons of carbon through 2023’s deployments. And again, that’s not a modeled thing, we actually measure the carbon that we remove.

“We are hoping to capture at least ten thousand metric tons of carbon through 2023’s deployments. And again, that’s not a modeled thing, we actually measure the carbon that we remove.”

-Mary Yap

That is what our plans look like for 2023. We are technically very young. We are ten months old as a company, we’ve not been around even for a year yet, but in our first ten months of activity and deployment, I think we’re on track to capture about two thousand metric tonnes. That’s from our first set of deployments. We’re working on scaling up, we’re working with row crop farmers and other kinds of farmers across America. and we’re also very open to helping other international parties with their own processes. So we’re happy to do the technological innovation for them and help them optimize their carbon removal rates, help make this safe for farmers, help them do some of the MRV. If you want to go fast, you go alone, but if you want to go far, you don’t go alone. So we’re very open to partnering. We have some of our first partnerships live today, including Yara, which is a massive multinational agricultural company that we are so excited and inspired by. We’re also helping their farmers capture carbon permanently in farms. So we’re very excited about expanding our scale, impact, and reach, through working with folks that are experts at already working with other farmers.

Wow. That is awesome. Your company is way further along than I thought you were!

We try to move fast. I come from a computer software background where you can build things to scale quite fast. Moving basalt is not quite as fast as consumer software, but we care very much about scale and rate of learning. So we are live today, we’ve been live for a while, we have a lot of farms both live and on the waitlist. And we’re also working with international partners, which we’re so excited about. Because enhanced rock weathering can happen everywhere-the Himalayas, et cetera. We want to empower other communities to have these benefits to their bottom lines. My family are smallholder, teeny tiny farmers in Taiwan, and some of the benefits for smaller farmers are actually even bigger than for the massive farmers that Lithos works with today. We would love to figure out how to expand our impact and our CDR scale and reach by helping other folks who are similarly climate motivated.

You’re adopting many of the most valuable principles I’ve read about, like rate of learning. I’m impressed, honestly! This is really cool

That’s so kind of you. I am going to say that we are still in the nascent stages. We are always learning, we want to take a humble approach to this. There is still so much more that we are still learning from our farmers. I always tell the team, we should be learning something from one in every three farmers, if not every single farmer. We are still nascent, we are still learning. We are partnering with different academic institutions, different extension officers, different soil researchers to figure out questions that I’ve never thought about before, different agronomic benefits and nutrient release cycles and all this. There’s so much more that we want to partner with more folks to work on. We’ve got the fields! If more researchers want to come research on these fields, please reach out. If we want to go far, we have to go together. Lithos is not super protective about everything we do, we’re here to make a climate impact, not just to build a business. I do think businesses are one of the best ways of making impacts, but we want to partner with folks who are better experts than we are. I do appreciate you saying that, and I’m also excited about what you’re doing, democratizing climate research and climate impacts.

“We’ve got the fields! If more researchers want to come research on these fields, please reach out…Lithos is not super protective about everything we do, we’re here to make a climate impact, not just to build a business.”

-Mary Yap

What are our thoughts on what ordinary people should know about climate change in general and enhanced mineral weathering in particular? And really anything else you'd like to share.

The key takeaway that I would love for folks on the street to have about climate, for one, requires a little explanation. There’s a lovely Calvin and Hobbes comic strip where Calvin and Hobbes are looking up at the night sky, and one of them says something like, “If human beings looked at the stars every single night, we would live our lives a lot differently.” When it comes to the climate, that’s what we should do. I live in San Francisco. Once a year, the sky turns orange from all the wildfires. Look around at the world that we live in that has allowed us to flourish, and realize that we are making a real impact on that. We are part of the ecosystem. It’s not just something that we need to conserve and take care of. It also takes care of us. Spend enough time in nature, you will realize the climate crisis is upon us, and we need to tackle it, and we have a shared responsibility there. Some people will take that as, become a poet, become a researcher, leave your tech job and go over to climate tech. Finding that fount of curiosity and wonder in yourself is probably the best way for folks to realize they want to help with the climate crisis.

“We are part of the ecosystem. It’s not just something that we need to conserve and take care of. It also takes care of us. Spend enough time in nature, you will realize the climate crisis is upon us, and we need to tackle it, and we have a shared responsibility there…Finding that fount of curiosity and wonder in yourself is probably the best way for folks to realize they want to help with the climate crisis.”

-Mary Yap

Some other things that are technical, and probably more relevant here, are about the CDR and enhanced weathering space. I think that it’s so important for people to realize, especially with all the snafus going on with CDR today and with carbon offsets, I think it’s really important for people to realize that there are legitimate, credible solutions to the climate crisis that can do permanent, additional, verifiable carbon removal. And that we need to be very intentional in our investments of time, resources, research, and money into figuring out how to make a credible carbon market that will scale. And that just sounds not exciting and very technical, but I think that’s so important. Because if we want these climate solutions to scale, we need to take responsibility for what we’re deploying out in the wild. My takeaway there is that there are real, scalable climate solutions that can be credible, and I hope folks will take a look at that and don’t just bunch all different climate solutions together.

And for enhanced rock weathering, I think it’s just an exciting space. It’s very inspiring to know there’s a method that nature’s biogeochemistry has invented for us that already sequesters billions of tonnes of carbon, and that we can actually speed this up. It’s going to take a lot of work and research and incredible thinking to continuously scale this to billions of tonnes [of enhanced weathering in addition to natural weathering], but it’s very possible today, we are working on it, and we would love to partner with folks who care about credible carbon removal, permanent carbon removal, and improving things for our farmers. Farmers are in some ways the bedrock of society. We don’t eat, things don’t look so good. So that’s what my takeaway would be: We are so lucky to be working in this space. We’re lucky to live on this planet, in this world. Our team is so thrilled to be working on this problem.

Wow. That was spectacular.

Thank you.

Is there enough basalt dust available for this to scale?